Research Thrusts

Main Thrusts

Our proposed research revolves around three main thrusts:

- Identify attack models specific to the scenarios considered, together with countermeasures based on measurements in the physical world;

- Develop abstraction and high-level planning algorithms that generate flexible plans that satisfy both the task specifications, and the additional security requirements;

- New low-level controllers that can negotiate the high-level plans with real-time objectives (such as obstacle avoidance) while allowing for collaboration between the agents. The proposed research includes an evaluation plan on a robotic testbed which includes camera-equipped ground and aerial vehicles, as well as short-throw projectors for creating augmented reality environments emulating our motivating applications.

Modeling physical masquerade attacks

We have formally defined the security problem of a

stealthy adversary masquerading as a properly functioning agent. perspectives from cybersecurity.

We introduced the concept of physical masquerade attacks in the context of multi-agent path finding, where a compromised insider in a multi-agent system attempts to gain access into unauthorized, forbidden locations without being noticed; we coined the term deviation attack for this type of malicious maneuver.

Right: if we add the a constraint that agents need to observe each other in the middle of their paths, neither agent can reach the secure location without breaking with the expected observation schedule.

We provide a constraint-based formulation of multi-agent pathfinding that yields multi-agent plans that are provably resilient to physical masquerade attacks. This formalization leverages inter-agent observations to facilitate introspective monitoring to guarantee resilience. Furthermore, we have show that is important to distinguish between a cautious attacker (i.e., an attacker that aims to avoid detection under every possible circumstance) and a bold attackers (i.e., attackers that tolerate a risk of detection)

ADMM Optimization for Multi-agent Path Planning with Spatio-Temporal Constraints

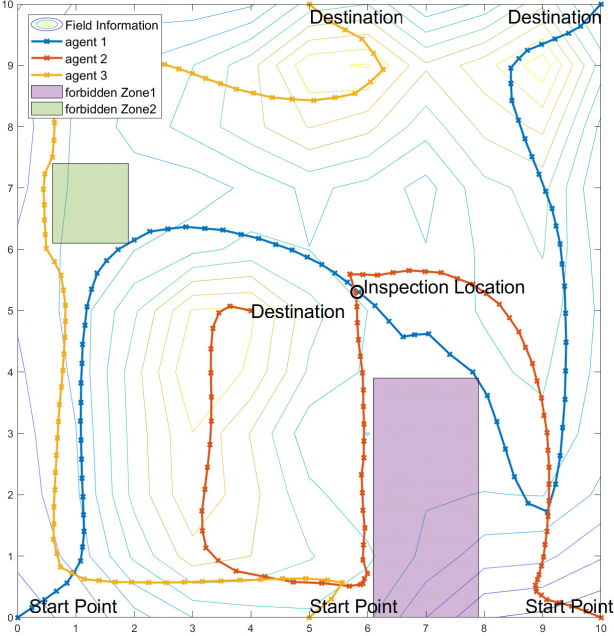

As part of Thrust 2 of our project, we study novel algorithms for multi-agent path planning for continuous environments with sound but incomplete detection guarantees but that can also pursue secondary optimization objectives.

As part of Thrust 2 of our project, we study novel algorithms for multi-agent path planning for continuous environments with sound but incomplete detection guarantees but that can also pursue secondary optimization objectives.

Path planning based on ADMM

We created a path planning method based on the continuous optimization Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) While ADMM is a well-studied algorithm from the optimization and machine learning literature). The resulting algorithm is very flexible, and can handle many different types of objectives and non-convex temporal-spatial constraints while allowing infeasible initializations. Although this approach can only ensure local convergence, when combined with a proper initialization, the algorithm empirically shows robust convergence, and the resulting paths have been tested on a multiagent experimental platform of iCreate robots.

Ellipsoidal bounds for deviation attack constraints

A challenge in the application, which was previously unsolved in the literature, was to enforce constraints that guarantee that an agent does not have a feasible deviation attack. As part of this optimization method, we therefore developed a type of differentiable constraint that is based on ellipsoidal bounds.

The foci of the ellipsoid are located at co-observation points or waypoints, while the radii are determined from the maximum speed of a robot times the period elapsed between co-observations or waypoints. The ellipsoidal region represents an upper bound on the set of points that can be reached by a robot between known locations.

We then proposed a definition of distance between a point or line segment and the ellipsoid that is differentiable with respect to the parameters of the ellipse. This then allows us to add constraints to the trajectories of a robot that guarantee the exclusion of a forbidden zone from the set of points potentially reachable by the robot between known or observed locations. Since the constraints are differentiable, they can be incorporated in our ADMM planner.

We then proposed a definition of distance between a point or line segment and the ellipsoid that is differentiable with respect to the parameters of the ellipse. This then allows us to add constraints to the trajectories of a robot that guarantee the exclusion of a forbidden zone from the set of points potentially reachable by the robot between known or observed locations. Since the constraints are differentiable, they can be incorporated in our ADMM planner.

Addressing infeasibility via additions of agents

When applying our ADMM-based path planning algorithm, we noticed that some problems are fundamentally infeasible; for instance, in some cases, pairs of agents are too far apart and cannot move fast enough to satisfy a given co-observation constraint. In these cases, we can still obtain a partial solution with our continuous optimization framework by ignoring this constraint. We have developed an extended method that transforms such partial solutions to full solutions that satisfy our notion of security constraints by adding a minimal number of new agents. In our method, the additional agents start on the same routes of the original agents (forming sub-teams). We then find a graph containing the original trajectories together with cross-trajectory segments representing opportunities for agents to change their membership across different sub-teams.

These segments are found by using a combination of RRT* (an optimal sampling-based algorithm) and validating such solutions using the ellipsoidal constraints previously developed in this project. We then find the assignment of agents to sub-teams and cross-trajectory edges as a multi-flow network optimization problem.

These segments are found by using a combination of RRT* (an optimal sampling-based algorithm) and validating such solutions using the ellipsoidal constraints previously developed in this project. We then find the assignment of agents to sub-teams and cross-trajectory edges as a multi-flow network optimization problem.

Note that there always exists a trivial solution where we can secure any plan by simply adding a second agent to each trajectory (such that each agent in a pair can always check on the other); however, our optimization procedure can typically reduce the number of agents while also improving security by preferring agents that move across sub-teams as often as possible (which, from our previous distributed blocklist work, it is known to improve the resilience of the system to multiple attacks).