New Research Grant for African Ajami Studies from the British Library

The Boston University Ajami Studies team received a new research grant from the Endangered Archives Programme of the British Library (EAP 1430), for a project “Digital Preservation of Fuuta Jalon Scholars’ Arabic and Ajami Materials in Senegal and Guinea.” The project that will commence in Spring 2023 will digitally preserve 50,000 pages of endangered Arabic and Ajami manuscripts (texts written with the modified Arabic script) produced by Fuuta Jalon scholars who lived between the 18th and early 20th century in the Republic of Guinea. The 50,000 pages of the endangered Arabic and Ajami manuscripts to be preserved in this project will include surviving texts of important scholars and handwritten copies made by their students, followers, and family members who keep them in their private libraries in the Fuuta Jalon region in Guinea and Senegal where the second largest Fuuta Jalon community in Africa lives. The archives to be preserved in this project will be the largest digital records of such materials in the world.

The project aims to advance existing scholarly knowledge about the rich bilingual works of Fuuta Jalon scholars. That knowledge is still very scarce, partly due to their country’s isolation after its independence from France in 1958, and the lack of public repositories of manuscripts. The texts deal with diverse topics such as astrology, divination, talismanic devices, Sufism, theology, panegyrics of Prophet Muhammad, Quranic exegesis, didactic materials in prose and poetry, elegies, grammar, philology, jurisprudence, calendars, history, biographies, genealogies, legends, commercial records, records of important events, diplomatic correspondences, pastoral poems on nature and rural life, and French colonization and its legacies. These materials could lay a foundation for future works on the legacy of Fuuta Jalon in the New World, and enable scholars, students, and the public to understand better how some enslaved Africans were educated and acquired Arabic and Ajami literacy skills before their captivity in the Americas.

Project Members Reflect on Their Work

In this series of blog articles, our NEH Ajami project members reflect on their work with the project:

- Dr. Bala Saho on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Mr. Ousmane Cisse on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Mr. Elhadji Djibril Diagne on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Dr. Mustapha Hashim Kurfi on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Mr. Boubacar Biro Diallo on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Mr. Ablaye Diakite on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Dr. Babacar Dieng on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Dr. Cheikh Mouhamadou Soumoune Diop on his work with the NEH Ajami project

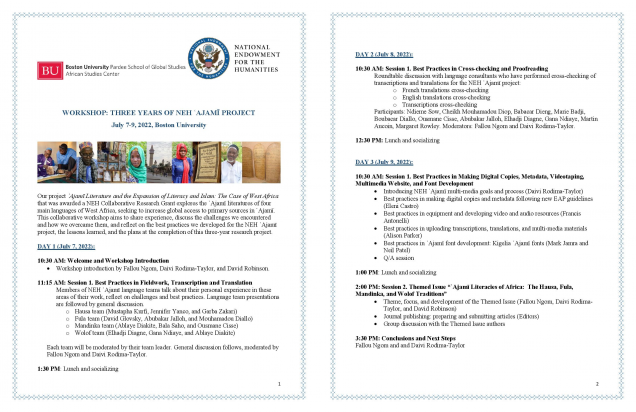

Collaborative Workshop: Three Years of the NEH Ajami Project

On July 7-9, 2022, the participants of the NEH-funded Ajami project gathered for a three-day workshop to share experience, best practices and lessons learned, and plans for the future. The three-year project, which started in September 2019, explores the Ajami literatures of four main languages of West Africa, seeking to increase global access to primary sources in Ajami. In the sessions of this collaborative hybrid workshop, the project members reflected on their experience with fieldwork in Africa, manuscript digitization, transcription, and English and French translation processes, interpreting Ajami manuscripts and writing academic articles. Participants also discussed the digital and technological aspects of the project. The goals of the workshop included identifying and sharing best practices in all of the project areas, and developing takeaways for the future. The workshop was attended by BU African studies faculty, research affiliates, staff, and graduate students as well as members of the Geddes Language Center, African Studies Library, and colleagues at partner organizations across North America and West Africa.

The NEH Ajami project comprises several important innovative aspects that create new opportunities for Ajami scholarship and everyday use in Africa, but also entailed certain novel challenges for the project participants. First, our project is the first systematic comparative approach to several African languages written in Ajami. It examines the different patterns of Ajami development in these four languages and literatures, the multiple forms and custodians of Ajami literacy, and the role of Ajami in the Islamization of West Africa. Secondly, it involves a systematic translation of Ajami manuscripts into English and French in order to enhance their accessibility, interpretation, and broad outreach – while most archival projects so far have been limited just to collecting and displaying Ajami manuscripts.

Thirdly, and most importantly, the NEH Ajami project has a unique participatory quality. With the help of our field teams and Ajami experts in Africa and the United States, it has aimed to facilitate interpretive knowledge about the meaning and purpose of Ajami texts, their social functions, and the voices of the people who have written, own, and use them. The project provides a unique bridge between archival knowledge and lived experience as it brings back the digitized texts of the past to their communities of origin to be read, chanted, and interpreted. Our field teams have conducted ethnographic interviews, conversations with chanters and singers, and collaborative transcriptions and translations of Ajami manuscripts, enabling us to observe the evolvement of the uses, contexts, and purposes of Ajami.

Our approach to displaying our material online reflects our commitment to continued collaborative research and broad visibility of African Ajami sources of knowledge. Our public web interface displays Ajami manuscripts, their metadata, transcriptions and translations, and related images of owners or collectors. This information is made publicly available and searchable for viewers globally. While digital modes of archival preservation as well as communication are becoming increasingly prevalent, this also brings along new challenges, inequalities, and digital divides. This calls for a particular attention to facilitating participatory knowledge-making processes during and after the research.

The workshop commenced on July 7 with an Introductory Session where project director Fallou Ngom and project manager Daivi Rodima-Taylor talked about the goals, history, and process of the multi-year project, and reflected on the important innovative and participatory contributions of the project’s work. The convened participants were welcomed on the behalf of the African Studies Center by ASC Assistant Director Eric Schmidt, and the workshop keynote by David Robinson outlined the main historical trajectories and importance of West African Ajami and implications for present and future research. In the following session, the members of NEH Ajami language teams shared their experience with digitizing Ajami manuscripts and interviewing manuscript owners and authors, transcribing the manuscripts, and translating them in English and French, and reflected on challenges, best practices, and takeaways from the project. The discussants included NEH Ajami project members Ablaye Diakite, Elhadji Djibril Diagne, Gana Ndiaye, Mouhamadou Lamine Diallo, David Glovsky, David Robinson, Abubakar Jalloh, Mustapha Hashim Kurfi, Jennifer J. Yanco, Garba Zakari, Bala Saho, Ousmane Cisse, Fallou Ngom, and Daivi Rodima-Taylor. In the session on July 8, they were joined by language consultants who had performed cross-checking and editing of transcriptions and translations for the project who shared best practices and challenges that they encountered. The session included contributions by Ndiémé Sow, Cheikh Mouhamadou Diop, Babacar Dieng, Marie Binta Badji, Boubacar Biro Diallo, Ousmane Cisse, Abubakar Jalloh, Elhadji Djibril Diagne, Gana Ndiaye, Bala Saho, Ablaye Diakite, Martin Aucoin, and Margaret Rowley.

In these sessions, team members discussed strategies for fieldwork that included the importance of working through local facilitators and elders to build trust with local manuscript owners and communities, explaining to them clearly the purpose of the study, and being respectful of their time, resources, and local customs. They also highlighted the need of giving feedback to local communities when the fieldwork is completed and sharing with them the digitized and translated texts, video recordings, and other output.

Team members discussed the importance of identifying and following standard orthographies, but also the complexity of many Ajami texts and the central role of local experts and contextual knowledge. In-depth cultural, historical and religious expertize was often necessary to fully understand the content of Ajami manuscripts, while one also had to consider the audience and purpose of the translated and interpreted material, to make it accessible for present-day readers. Due to their complexity, some manuscripts benefited from consulting with a team of local Ajami experts. Ethnographic research and knowledge was often indispensable for translating metaphors and other figures of speech. Interpolated commentary such as footnotes were found as effective tools for conveying all aspects of such contextual information and possible alternative interpretations.

Translation processes are further complicated by the fact that language changes, and historical texts therefore require particular care when conveying the meaning of certain words and concepts that may have been interpreted differently in the past. Dialectical variations of a language as used in different communities and regions pose another source of difficulty, as well as some cases of orthographic ambiguity where different vowels were represented by similar diacritics. Several members of the translation teams mentioned the usefulness of compiling glossaries of more complex terms as they proceeded through their work. Harmonizing the French and English translations of Ajami manuscripts also proved challenging at times.

The discussions devoted particular attention to making the research findings and materials accessible to local African communities, and explored the ways of facilitating the continued participation of African Ajami users and manuscript owners and authors in the collaborative interpretation and dissemination of the materials and findings of the project.

Discussions continued on July 10 with exploring the technical aspects of the project, including making digital copies of manuscripts, recording metadata, preparing video and audio files, building a multimedia website, and African Ajami font development. Frank Antonelli discussed the video production process for editing the project’s video and audio recordings and provided an overview of the most optimal equipment, lighting, and other aspects of recording in remote locations and frequently unpredictable field conditions. He also shared the experience of framing and embedding the project video and audio files. Daivi Rodima-Taylor provided an overview of the NEH Ajami multi-media goals and process, including the collaborative development of web pages and metadata forms. The presentation by Alison Parker explored the logistics of constructing a website and discussed best practices of uploading digitized manuscripts and multimedia files, reflecting on the technical steps that go into constructing and navigating webpage names, creating image captions, and embedding videos and slideshows. Eleni Castro’s presentation discussed the digitization and cataloguing guidelines of the Endangered Archives Programme at the British Library. Reflecting on best practices of imaging and recording for community-centered fieldwork, it examined proper equipment and techniques for image and audio capture in remote field locations, often without a steady supply of electricity and internet.

Focusing on the urgent issues of African typography, Mark Jamra and Neil Patel discussed the challenges of creating fonts that address traditional sub-Saharan, Sahelian forms in all of their variations. They explored the development of Ajami-specific keyboards and features for different language communities, proposing a strategy for achieving widespread availability of African Ajami scripts to everyday users.

This discussion was followed by a session focusing on academic publishing. The Editor of Islamic Africa, Joseph Hill, provided the workshop participants with a detailed overview of the content and scope of the journal, and suggested helpful guidelines for conceptualizing, writing, and submitting an article. The Islamic Africa journal, which publishes original research and primary source material concerning Islam in Africa from the social sciences and humanities, has been one of the foremost academic fora for African Ajami research. Rebecca Shereikis explored the history of the journal and the activities of its predecessor, Sudanic Africa, published by John Hunwick and R.S. O’Fahey.

The session also discussed the forthcoming Special Issue of the NEH Ajami project, “Ajami Literacies of Africa: The Hausa, Fula, Mandinka, and Wolof Traditions,” which offers unique comparative perspectives on Ajami use in four major West African languages, explores the role of digital technologies and methods in studying and preserving African Ajami manuscripts, and highlights the collaborative and multi-vocal knowledge production about Ajami texts, their social functions, and the people who have written and use them.

The workshop offered a productive collaborative venue for sharing experience and celebrating the three-year NEH Ajami project, and was attended by participating scholars and language consultants from Africa and the United States. The workshop reflections offered constructive lessons and takeaways for the dissemination of the project’s findings, as well as outlined trajectories for future research.

READ MORE HERE:

- Dr. Babacar Dieng on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Dr. Cheikh Mouhamadou Soumoune Diop on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Mr. Ousmane Cisse on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Mr. Ablaye Diakite on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Mr. Elhadji Djibril Diagne on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Dr. Bala Saho on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Mr. Boubacar Biro Diallo on his work with the NEH Ajami project

- Dr. Mustapha Hashim Kurfi on his work with the NEH Ajami project

NEH Ajami Collaborative Workshop, July 7-9, 2022

We are pleased to announce a three-day Workshop to celebrate and share experience from our research project ʿAjamī Literature and the Expansion of Literacy and Islam: The Case of West Africa, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The collaborative Workshop aims to reflect on the best practices we developed for the NEH ʿAjamī project, the lessons learned, and the plans at the completion of this three-year initiative. The Workshop will take place on July 7-9, 2022, virtually and at the Boston University African Studies Center. More details can be seen here: NEH Ajami Workshop Program

Lecture at IFAN, Senegal

Prof. Fallou Ngom delivered a virtual lecture on African Ajami on September 13, 2021 at URICA (Unité de Recherche en Ingénierie Culturelle et en Anthropologie) at the IFAN, Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal.

Towards Comparative Global Humanities

Dr. Daivi Rodima-Taylor presented on African Ajami at the conference Worlds Enough and Time: Towards a Comparative Global Humanities, organized by the MIT School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, November 12-13, 2021. The conference explored novel approaches to an integrative transformation of the Humanities through a radical foregrounding of geographical scope and temporal depth. It aimed to develop new comparative methodologies based on the world’s archives and conceptual vocabularies, to address the social, political, and creative functions of cultural heritage in today’s world and to advocate more effectively for social justice, cultural understanding and reconciliation. Conference presentations and collaborative discussions explored the ways in which forms of knowledge production and humanistic inquiry from other times and places could inspire a productive transformation of today’s humanities, while taking inspiration from the historical experience and textual archive of non-Western and marginalized knowledge cultures and traditions.

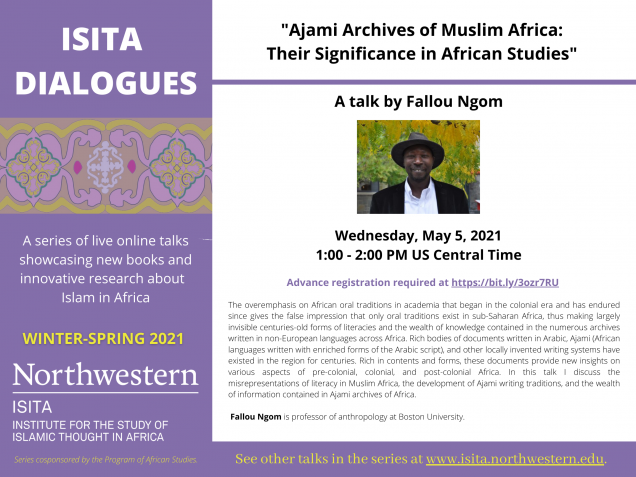

Fallou Ngom presenting at ISITA

New Federal Grant Award: Readers in Ajami

The team of Ajami scholars at Boston University, led by Professor Fallou Ngom, has been awarded a three-year grant of $178,900 by the U.S. Department of Education to develop specialized Ajami readers in Hausa, Wolof, and Mandinka (three major African languages with rich written Ajami literatures) with a multimedia companion website. The Readers in Ajami (RIA) project will provide students, language teachers, scholars, and American professionals with the necessary linguistic, cultural and literacy skills to engage Ajami users of West Africa. The resources of the project will cover a range of fields, including business and economy, health and medicine, agriculture and the environment, and human rights, politics and diplomacy. The project will produce a methodology that can be replicated for other world languages with dual literacy systems (Ajami and Latin script orthographies). It will provide an optimal model of how to build and sustain specialized textual and digital educational resources that incorporate local voices and knowledge recorded in multiple African Ajami scripts – something many academics and professionals have overlooked for centuries. The project draws on the expertise at BU and overseas in Ajami, African linguistics, pedagogy, social anthropology, and digital technology. Our team, led by Professor Ngom, includes Dr. Daivi Rodima-Taylor, Dr. Jennifer Yanco, Dr. Mustapha Kurfi, Mr. Ablaye Diakite, Mr. Elhadji Diagne, Dr. Bala Saho, and the Geddes Language Center digital specialists Alison Parker, Shawn Provencal, and Frank Antonelli.

Rodima-Taylor Published Work on Digital Infrastructures

Dr. Daivi Rodima-Taylor, Project Manager of NEH Ajami, published several articles recently focusing on the role of digital technologies in mediating local and global distributions of power. She co-edited a special issue "FinTech in Africa" (with Langley, in Journal of Cultural Economy) and authored an individual article on the fintech political economy of self-help. Her review article “Promise, Ethnography, and the Anthropocene: Investigating the Infrastructural Turn” (in American Anthropologist) examines the role of contemporary infrastructures in in exacerbating the environmental and social challenges of the Anthropocene and explores their potential to distribute material and knowledge resources in novel, sustainable ways. The article “Interrogating Technology-led Experiments in Sustainability Governance” (with Bernards et al., in Global Policy) suggested novel pathways for exploring key ethical, social and political considerations involved in the increasingly technological solutions to global sustainability issues. Another collaborative article, “Global Regulations for a Digital Economy: Between New and Old Challenges” (with Beaumier et al., in Global Policy), examined the unique challenges posed by digital technologies to regulators and policy-makers on local, national and global levels. Daivi's recent co-edited book, Land and the Mortgage: History, Culture, Belonging holds her chapter "Land, Finance, Technology: Perspectives on Mortgage Lending." Her recent work also explores the intersection of the local and global in digital remittance infrastructures, and the legitimacy of digital development in small states. The social study of algorithmic power was highlighted at a co-organized symposium “Law, Ethics, Culture: The Human Face of Artificial Intelligence” at the University of California, Irvine.

Digitizing Past and Present: Our Geddes Digital Humanities Team

By Mark Lewis and Daivi Rodima-Taylor

The Geddes Language Center of Boston University is one of the integral partners of our NEH-funded Research Project on Ajami Literature and the Expansion of Literacy and Islam: The Case of West Africa. The Geddes Language Center is a full-service language learning facility dedicated to providing an extensive humanities resource for the College of Arts and Sciences and the Boston University community. Founded in 1960, the mission of the Geddes Language Center is to support the teaching and learning of languages, literatures, cultures, and film as faculty introduce new learning modalities and resources, both in the classroom and online.

The collaboration with the Geddes Digital Humanities Team under the leadership of Mark Lewis provides a unique multi-media component to our archival and research project. Geddes web designer Alison Parker and director of programming Shawn Provencal provide the website design and coding elements to accommodate the digital repository and display of Ajami manuscripts, their transcriptions and French and English translations, in four West African languages – Wolof, Mandinka, Hausa and Fula. Video resources specialist Frank Antonelli processes and edits video and audio files that form an important part of the NEH Ajami project, and advises project scholars on the use of multi-media equipment.

Geddes has a long-standing collaboration with the BU African Studies Center. This includes the African Language Materials Archive (ALMA) that is a multi-partner project focusing on the promotion and documentation of literature and literacy in the languages of Africa. This archive holds a collection of cassette recordings from the 1980s, made during field research in a number of different Sahelian and desert countries. Many of the transcriptions accompanying these recordings were translated into Western languages, mostly French or English. This collection, known as At the Desert’s Edge, involved hundreds of interviews of every-day people in traditional societies. Researchers engaged them in discussions of the ecological conditions of their existence and the state of the environment in their countries.

The countries that are part of the ALMA project are Burkina Faso, Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and the Sudan. The project represents one of the largest digitization initiatives the Geddes Language Center has undertaken in more than a decade, and will likely continue for the foreseeable future. All coordination and technical work is done by Frank Antonelli, Video Resources Specialist. The primary material of this collection was digitized during the years of 2016-2019.