Food Mapping at H-Mart

Students Karen Metheny’s summer course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) are contributing guest posts. This food mapping example comes from Gastronomy student Jie Liu.

Food mapping is a tool that can be used to figure out where people buy and eat food, what their preferences are, and how they behave in a food system. In this entry on food mapping, you will clearly see how people move through the space and what connections people create through food. I will connect my observations to three different aspects of food mapping to see what we can learn from this practice.

I chose H Mart, a popular Asian supermarket chain in America, as the site of my mapping observation. This specific supermarket has a small food court with three vendors: Paris Baguette Café, Go Go Curry, and Sapporo Ramen. It is a very good place to have a meal and a cup of coffee, and then buy some groceries, all at one stop. Besides the supermarket, Paris Baguette Café is another reason that I come here very frequently. This international and premium bakery-café brand was founded in 1998. It serves a variety of treats—not only breads, pastries, and cakes, but chef-inspired sandwiches and salads, and different kinds of drinks. I chose to observe the food court, especially paying attention to Paris Baguette Café. I was hoping to get more information about how people interact within this area, and in relation to the environment.

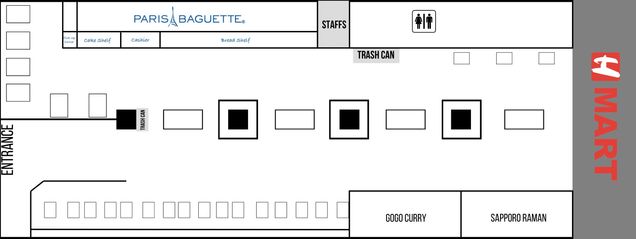

H Mart is located at 581 Massachusetts Avenue and is just steps from the Central Red line which is a very easy destination for costumers. Beside the large logo of H Mart in front of the main entrance, people also can see the signs for three vendors, but especially Paris Baguette Café. The Cambridge H Mart food court area is clean, sleek, and well organized. The appealing inner decoration, the clean environment, and the exotic food extend the role of H Mart beyond its function as a supermarket to a destination for dining and a place to relax. There is a modern and organized bakery-café store you can see first when you enter from the main gate. As you can see from the map (Figure 1), in the upper left corner, there are six tables with leather sofas belong to the café. All six tables seat four. In the center of this space, there are four main pillars. There are at least 50 seats available along the pillars. The bottom area in the map shows there are two other stalls: Go Go Curry and Sapporo Ramen. Moreover, there are around 30 seats beside these food stalls. All these tables and chairs use the same white color and unified material, which makes the environment bright and tidy.

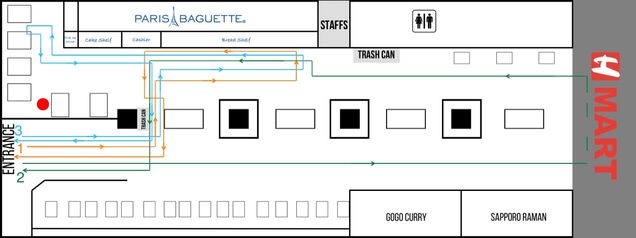

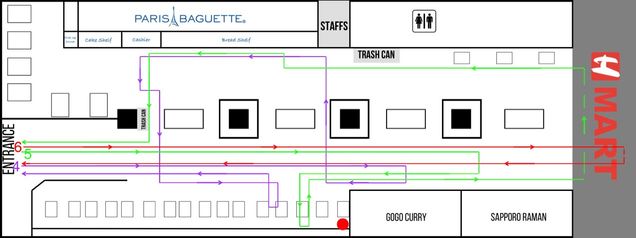

I arrived at the food court at 10:30 am on Thursday morning. I decided to observe the space for at least 2 hours. I chose this time range because it was not lunch time during the first hour from 10:30 to 11:30. And more people would come here for lunch in the second hour from 11:30 to 12:30. In the first hour, I chose the table that is not far from Paris Baguette Café cashier which is the red dot shown in Figure 2. This spot was close to the entry, and also gave me a great view of the whole café. One hour later, I changed my seat to the red dot in Figure 3, so that I could observe more clearly the people who came to have lunch.

The first interesting finding in my data is the vast majority of the customers at Paris Baguette Café were women, unaccompanied or only with their kids. There were very few male customers at the café. Even during the lunch time, the most people who went to Paris Baguette Café to buy a drink or a dessert were women as well. How do we explain this? Scholars like Bentley (1998) suggest that we look closely at gender in foodscapes. Bentley argues that red meat is associated with masculine virility, while sugar has been identified with femininity by other scholars (e.g., Avakian and Haber 2005). According to Farnham (2014), in Brtitain “men are more likely to visit a coffee shop on a daily basis, whereas women are more likely to visit 2-3 times a week. Women tend to stay longer once they get there though and they are more likely to use a coffee shop for socializing as well. Women are also more adventurous than men in the new drinks they are willing to try.” This phenomenon is worth exploring at Paris Baguette Café at different time periods and on different days.

According to my observation, I found that most people who come to Paris Baguette Café would like to spend a little time in front of the bread display cabinet, even if some of them didn’t buy anything. As Huddleston and Minahan (2011, 108) observe, “Creative and attractive merchandise displays draw customers in.” However, unlike most coffee shops today, Paris Baguette Café in the H Mart doesn’t have power sockets and WIFI. Although the café offers a very comfortable dining area for its guests, there would be more customers if they provided this supplementary service.

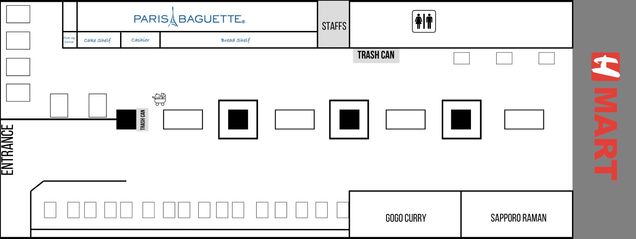

Another interesting conclusion I noticed involved the pattern of foot traffic. As you can see from the map, people always chose the narrow path opposite the cashier as an exit, regardless of which direction they came from. Nevertheless, if someone used the table between the first two pillars which are close to the main entrance, especially a mother with a stroller, that narrow path would be blocked (Figure 4). Meanwhile, with the increasing number of customers at the peak time, the two main pathways on both sides of the middle seating area became very messy. There is no defined place to queue while customers are buying the food. The issue is worth exploring more to create a better idea to use the space.

Unlike food observation, food mapping can be used as a tool to promote dialogue with retailers and policy makers. Food mapping could help bring positive change and effective strategy. As Wight and Killham note (2014, 314), “Food mapping is a new, participatory, interdisciplinary pedagogical approach to learning about our modern food systems. […] This experiential exercise encourages participants to look beyond their plates and think about the health, economic, and ecological impacts of food.” Moreover, food mapping can describe physical and economic relationships with food, and illustrate people’s preferences and behaviors. The effort and meaning involved in producing meaningful food maps should never be underestimated.

References

Avakian, Arlene Voski, and Barbara Haber, eds. 2005. From Betty Crocker to Feminist Food Studies: Critical Perspectives on Women and Food. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Bentley, Amy. 1998. Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics of Domesticity. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Farnham, Jacqui. 2014. Women and the Coffee Shop Revolution. Business Boomers. BBC Two. Date of access, June 07 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2QHz8CcHJV1wqxSjK77M4q7/women-and-the-coffee-shop-revolution

Huddleston, Patricia, and Stella Minaha. 2011. Consumer Behavior Women and Shopping. New York: Business Expert Press, LLC.

Wight, R. Alan, and Jennifer Killham. 2014. Food Mapping: A Psychogeographical Method for Raising Food Consciousness. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 38(2): 314-321.