Structure and Motivation: Reading Historic Cookbooks

by Barbara Rotger

culinary collection honorary curator,

Harvard Schlesinger Library

When Barbara Wheaton, honorary curator of the culinary collection at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library, refers to taking a structured approach, she means it. As a participant in her recent seminar on Reading Historic Cookbooks, each day’s work was to have a theme, such as “ingredients” or “cook’s equipment” and each participant was assigned a text to which to apply that theme. It is tempting to dive in to a cookbook and try to take it all in; focusing on a single element at a time ensures a kind of thoroughness that is necessary for an appreciation of the work as a whole.

That meant no conjectures about the publisher’s motives when we were supposed to be focused on ingredients and no thoughtful analysis of cooking equipment when the focus was to be on the structure of the meal. Wheaton further cautioned us as to the limitations of using cookbooks as sources (do not even begin to think that they will tell you what people ate!), and emphasized the need to complement their study with sources such as maps, letters and diaries, art and architecture, and economic data.

The seminar participants, an eclectic group of scholars and practitioners, were eager to delve into the books that Wheaton had selected for the week. We began by drawing lots to learn which cookbooks we would work with each day, texts that ranged from fifteenth century British manuscripts to twentieth century American community cookbooks. With my interest in twentieth century recipe boxes, I hoped for the latter, only to find that I would be starting by examining ingredients in the 1587 edition of Thomas Dawson’s The Good Housewife’s Jewel. Quick to read my mind, Wheaton reminded the group of her “no trading” policy: we were to push our own boundaries, and move out of our own comfort zones.

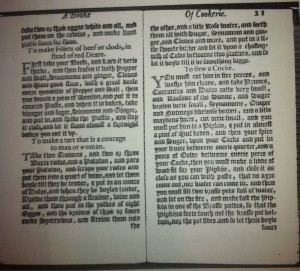

“To make a tart that is a courage to a man or woman”

And so I proceeded, well outside my comfort zone, with a browser open to the OED, trying to draw conclusions from the ingredients listed in the Jewel. My eyes strained to decipher the blackletter script, with its long s’s that look like “f”s and my brain struggled with non-standard spelling. For my presentation to the group the next day, I settled on a recipe “To make a tart that is a courage to a man or woman.” In this kind of work you can look for patterns, or look for outliers; the ingredients for the tart provide examples of both. Typical flavorings, including rose water, sugar, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, and mace, appear in this and many other recipes in the book, while a few ingredients stand out. The recipe calls for a “potato” which struck me as a very early occurrence of a new-world food, until my excitement was tempered those better versed in this time period, who explained that a sweet potato was what the author had in mind.

I was similarly stumped by the call for “the brains for three or four cock sparrows” in the recipe. (I have examined my share recipe boxes and not one sparrow brain—male or female—has been used as an ingredient.) As I struggled to explain this in my presentation, Barbara Wheaton, with a twinkle in her eye, silently but clearly mouthed the word “aphrodisiac” to the rest of the group. Perhaps the structured approach has its limits: to understand some ingredients one must also consider the structure of the meal—and the motivations of the cook!

——————-

Recipe “translation”: To Make a tart that is a courage to man or woman

Take two quinces and two or three burre roots and a potato and pare your potato and scrape your roots and put them into a quart of wine and let them boil until they be tender, and put in an ounce of dates and when they be boiled tender drain them through a strainer, wine and all, and then put in the yolks of eight eggs and the brains of three or four cock sparrows and strain them into the other a little rose water, and seeth them all with sugar, cinnamon and ginger and cloves and mace, and put in a little sweet butter and set I upon a chaffing dish of coals between two platters, and so let it boil until it be something big.

Barbara is a Gastronomy program alumna, mother of two, and the Gastronomy Program coordinator since October 2011. Read more about her life and work.