CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

Trauma of Institutionalization: Is It Possible That an Ex-Convict Will Recidivate Due to Institutionalization?

To begin this blog, I would like to quote: “With one in every 108 Americans behind bars, the deinstitutionalization of prisons is a pressing issue for all those facing the daunting challenges of successfully reintegrating ex-offenders into both their communities and the larger society” (Frazier, Sung, Gideon, & Alfaro, 2015).

Similar to military life, prison is highly structured. The Prisoner is immersed in a disciplined environment where their daily activities are monitored and planned. This raises an important question: might an ex-convict struggle to reintegrate into society after spending so much time in the controlled environment of prison life? When combined with prior trauma—whether biological, developmental, or social—as well as learned behaviors from their neighborhoods, social groups, and the prison system, could this contribute to the high recidivism rates among ex-convicts (Bartol & Bartol, 2021)?

Moreover, both combat veterans and former convicts might experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a higher level than those in society due to the trauma of institutionalization and the stress they endured while in these settings (American Psychiatric Association, 2025). While the life experiences of these two groups may differ, the process of becoming institutionalized in either environment increases the likelihood of issues such as drug abuse, violent tendencies, and antisocial behavior. This is because participation in such systems often requires individuals to suppress their individuality for the greater good of the institution. This lack of individuality can make it harder for them to adapt once released, potentially leading them back to crime as it may be the only environment they understand.

Another quote that helps us understand the need for change states: “Social voids like those created by deinstitutionalization must be filled; and with states deinstitutionalizing offenders, the toll is on their corresponding communities to address the needs of those offenders who are reentering after being incarcerated” (Frazier, Sung, Gideon, & Alfaro, 2015).

Both groups often develop a strong sense of belonging to the communities they were part of. While many combat veterans learn to cope with stress in healthy ways, convicts may become so indoctrinated by the criminal justice system that they are unable to reintegrate into society. If this happens, they might resort to committing crimes in an effort to return to the only environment they genuinely know.

It is also interesting to note that, in order to become a police officer, one must be at least 21 years old, while the minimum age to enlist in the military is typically 18 or even 17 with parental consent. The frontal lobe, which is responsible for decision-making and impulse control, continues to develop throughout these years. This suggests that society may prioritize younger individuals for law enforcement or military service roles because their brains are still developing and are, therefore, more malleable. Furthermore, an adolescent convict’s brain continues to develop up until they are around 25, meaning their development within the carceral system might be hindered by institutionalization.

These parallels are both intriguing and deserving of further exploration.

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2025). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., Text Revision). https://doi.org/10.5555/appi.books.9780890425787.x00pres

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (12th ed.). Pearson.

Frazier, B. D., Sung, H.-E., Gideon, L., & Alfaro, K. S. (2015, May 6). The impact of prison deinstitutionalization on Community Treatment Services. Health & Justice. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5151559/

Trauma-Informed Care as Part of a Gender-Responsive Approach in Criminal Justice

The role of trauma and the way in which it is experienced within the criminal justice system is something we have explored throughout our course. I have found that you cannot talk about progressive changes and addressing needs in the criminal justice system without talking about trauma. This is especially true when thinking about the experiences of incarcerated women before, during, and after their involvement in the system. While trauma and mental health issues are pertinent to all incarcerated individuals, the unique experiences of women can go overlooked and current approaches for assessing risk and needs are informed by male normative standards (Hannah-Motaff, 2006). This means current approaches might fail to address the unique experiences and needs of women offenders which often involve trauma.

In my exploration of the benefits of trauma-informed and gender-responsive approaches for women, I found Bloom and Covington's Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Women Offenders (2008) to be incredibly informative and a clear call to action for incorporating trauma-informed care in the treatment of incarcerated women. As Bloom and Covington point out, female prisoners and jail inmates often have more mental health problems than male prisoners, with especially high levels of interpersonal trauma and experience with domestic violence. This is significant when we consider that incarcerated women might not be given resources and interventions that are designed to help them process and heal from trauma during their involvement in the criminal justice system (and after it). That being said, we can think of the gender-responsive approach as one that highlights the need for trauma-informed care and empowerment for incarcerated women.

I think when discussing trauma-informed care and gender-responsive approach, we should avoid presenting these as abstract concepts and instead be clear about how to practically apply these in the criminal justice system. I personally find Bloom and Covington's suggestions to be reasonable and helpful. They outline what a trauma-informed approach can look like: acknowledging women’s unique trauma histories, creating a safe, supportive environment that promotes healing, providing psychoeducation about trauma and abuse, teaching coping skills, and validating women’s reactions. I would add that fostering a culture of understanding and safety is crucial along with giving women autonomy in their treatment planning/goals, encouraging empowerment.

Trauma-informed and gender-responsive care requires comprehensive training of staff and the resources to hire quality mental health professionals. While this may require more funding, the potential positive outcomes from this approach are significant and justify the investment. Trauma-informed care is crucial for incarcerated women to meet the goal of reduced involvement with criminal activities (Bloom & Covington, 2008). Directly addressing traumatic victimization experiences, functional difficulties, and other mental health needs is a step toward rehabilitation and positive outcomes for incarcerated women. My takeaway here is that gender-responsive care for incarcerated women must be trauma-informed. This is done by creating a safe, supportive therapeutic environment that empowers women and promotes healing.

References:

Bloom, B. E., & Covington, S. S. (2008). Addressing the mental health needs of women offenders. In Women's mental health issues across the criminal justice system. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hannah‐Moffat, K. (2006). Pandora’s box: Risk/need and gender‐responsive corrections. Criminology & Public Policy, 5(1), 183–192.

Self-Care After Trauma

After experiencing trauma, self-care can be a vital step in regaining a sense of safety, and self, and not only comfort but help with managing stress during a time of healing. It is centered around taking steps toward feeling healthy and comfortable whether the trauma endured has been physical, mental, or both. Healing is a process.

It is important to know that trauma reactions are normal reactions in exceptionally abnormal situations (McNeilly, 2015). There is no typical reaction or required response after experiencing trauma. However, some reactions that can be experienced are emotional and psychological, cognitive, physical, and behavioral. By addressing these reactions we can establish ways to manage them while incorporating the self-care necessary for healing and recovery.

Physical, cognitive, and behavioral responses can manifest in numerous ways. Physically, a person can experience symptoms such as headaches, nausea or upset stomach, being easily startled, fatigue, high blood pressure, dizziness, rapid breathing, and insomnia. Cognitive responses include difficulty concentrating, flashbacks, amnesia, or worry. Finally, behavioral responses can be experienced as changes in sleeping and eating patterns, withdrawal from others, or not wanting to be alone (MITHealth, n.d.).

During a person’s recovery, they should be aware of their physical health. Being physically healthy can help support you through times when a person is feeling emotionally drained or recovering from physical injuries. Honesty with oneself and their support system is imperative to ensure that healing can happen.

In the physical sense, we can reflect on times when we did feel physically healthy. When doing so, we should address questions such as: how were sleep habits during this time? How were your eating habits, and what made you feel healthy, strong, or even comforted? Did you exercise? Did moving your body more make you feel better? Did you participate in previous self-care or daily routines that helped improve your day, start your day off well, or contribute to winding down in the evenings? (RAINN, n.d.).

By answering these questions, we can start to rebuild or take from the previous habits or routines and incorporate them into physical recovery by repeating or taking examples from these times. Furthermore, it is important to allow yourself to rest when you need to rest and do things that feel good to you.

Emotional self-care comes in many forms. It is not a one-size-fits-all routine, but as unique as the individual involved. By being able to recognize the signs of psychological and/or emotional distress we have a better chance of addressing them. These reactions can manifest in several ways such as fear, panic, or generally feeling unsafe, anxiety, flashbacks, anger, irritability, moodiness, crying, feelings of helplessness or meaninglessness, depression, violent fantasies, detachment, “survivor’s guilt” or self-blame, restlessness, over-excitability, hopelessness, and feelings of estrangement or isolation (MITHealth, n.d.).

Much like with our physical health, we can ask ourselves questions about times when our emotional health was in a better place. In doing so, we can reflect on how we can start trying to rebuild back to that place. Where did you spend your time? Who did you spend your time with? Did you feel safe and supported when you were with them? Where did you draw inspiration from during this time? Is there a particular book, quote, or even a Pinterest board where you put away things that made you feel good or happy? Did you like to meditate or journal? What did you like to do for fun? How did you relax? (RAINN, n.d.).

Being reminded of these times and these habits can help bring back into focus that there were times when the world wasn’t so overwhelming and there can still be those times again. Using the same habits from then can help work through the trauma a person has experienced by doing things they know have made them happy previously.

There are many types of self-care, emotional, financial, spiritual, professional and academic, mental, physical, environmental, recreational, and social (Reiff, 2024). Sometimes self-care, especially after trauma requires deliberate effort. This can be sleeping, showering, eating, watching television, reading, or going for a walk, as much as it is acknowledging the trauma, going to therapy, talking about the event with those you feel comfortable with, and learning your trauma triggers. You must allow yourself to feel your feelings. No matter what they are your feelings are valid and you are allowed to feel however you want to about what happened to you.

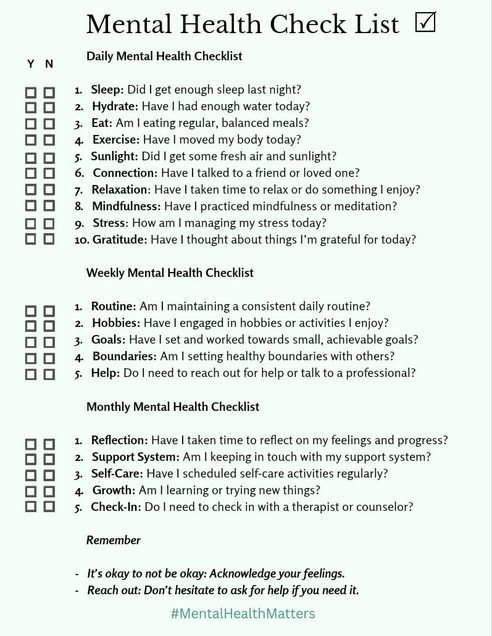

If you are feeling unsure of how to start practicing self-care, here are a few lists of ideas for you:

References:

McNeilly, C. (2015, September 23). Taking Care of Yourself After a Traumatic Event | University Counseling Service - The University of Iowa. Counseling.uiowa.edu.

https://counseling.uiowa.edu/news/2015/09/taking-care-yourself-after-traumatic-event

FAQ: Common Reactions to Traumatic Events | MIT Health. (n.d.). Health.mit.edu. https://health.mit.edu/faqs/mental-health/common-reactions-to-traumatic-events

Self-Care After Trauma | RAINN. (n.d.). Rainn.org. https://rainn.org/articles/self-care-after-trauma

Reiff, L. (2024). 9 Types of Self-Care & How to Practice. ChoosingTherapy.com.

https://www.choosingtherapy.com/types-of-self-care/

Girlspring. (2020, March 28). Self-Care Check List! - GirlSpring. GirlSpring.

https://girlspring.com/self-care-check-list/

TheMindsetGarden. (2024, July). Benefits of a Mental Health Checklist. Payhip.

https://payhip.com/TheMindsetGarden/blog/mindset/benefits-of-a-mental-health-checklist

Teachers’ Secondary Stress and Trauma After School Shootings

Recently we were asked to explore the different typologies and characteristics of multiple murderers. Within this context, the characteristics of school shooters were also explored. According to Bartol & Bartol (2021), school shootings are not a common occurrence; however, in my opinion, they are far too common. There is no other country that experiences as many school shootings as the United States (Bartol & Bartol, 2021). In 2024, there were 39 school shootings that resulted in injury or death. At least one school shooting happened each month in 2024 (Lieberman, 2024). In my opinion, these numbers are astounding.

Bartol & Bartol also revealed that when school shootings do occur “…they generally involve one perpetrator who shoots a small number of victims and is promptly taken down…(Bartol & Bartol, p. 358). In a recent class discussion, I expressed my concern about this quote. As an educator in an urban public high school, this assertion deeply struck me. What is the definition of “victim” in this context? Is victim defined here as those who died during the commission of murders? Care should be taken to acknowledge those who may not have died or been physically wounded, but will experience lifelong psychological trauma as a result of being present during the tragedy. Parents, families, and friends of those who were injured or killed; students and teachers who were present during the shootings; students and teachers in cities, states, and countries outside of where the incident occurred – these individuals are also victims.

I am one such victim. I was never able to put a name to it, but after reading Dr. Rousseau’s lecture on secondary trauma, I was relieved by the clarity it provided. While I am privileged to have never been embroiled in a school shooting, each time I hear about a school shooting, I am devastated. When these tragedies occur, there is little to no support provided for teachers in my school building, which seems to be a commonality among other districts as well. For instance, after the Sandy Hook murders, teachers who experienced secondary trauma were not offered support by their schools’ administration. (Dixon, 2014). The day following the Abundant Life Christian School shooting, I overhead a student talking about making a bomb. I immediately reported him to school counseling and he returned to class less than 5 minutes later.

It is difficult for me to walk into my school building each day knowing that is not equipped with metal detectors. District leaders’ theories regarding the effects of metal detectors on teacher and student morale, especially in a community that serves mostly Black and Latino students, deters the installation of what I consider such a necessary tool (Jenkins, 2024). It is difficult to acknowledge the pervading fact that a student can enter the school with a weapon – undetected – and the incessant worry of tragedy striking my school. The implementation of safe mode drills, which are designed to prepare students and staff in the event an active shooter is on campus, only adds to the trauma experienced in a space that is supposed to feel welcoming and safe. Additionally, due to the unpredictable nature of school shootings(Bartol & Bartol, 2021), I do not believe the implementation of these drills effectively prepares students and school staff. My hope is that broader consideration will be given to all victims who suffer from school shooting related trauma and everyone involved receives the necessary supports to live better and more productive lives.

Child Psychopathy and the Role of Trauma in Development and Treatment

Child psychopathy is a controversial yet more and more studied topic within psychology and criminal behavior research. While the term “psychopath” is saved for adults, children can exhibit traits associated with psychopathy, including cruelty, persistent lying, impatience, and lack of empathy toward others (Bartol, Bartol 2021). Understanding how these traits develop, the role of trauma, and early interventions is important in addressing potential long-term behavioral issues and criminal activities.

The Relationship Between Trauma and Psychopathy

A major argument in child psychopathy research is whether these traits can even be attributed to genetic predispositions or as a response to environmental influences, like trauma or parental styles, or a combination of factors.

· Genetic Predispositions: Some children display psychopathic traits despite being raised in loving and stable homes. Studies show that these children may have structural and functional differences in brain regions associated with emotion processing, such as a smaller, less active amygdala, responsible for the ability to recognize fear and distress in others, and struggling to regulating emotions (Yang, Raine, Narr, Colletti, Toga 2009). This could suggest that for some individuals, psychopathy may be an genetic condition rather than a learned behavior.

· Trauma-Induced Lack of Empathy: Children raised in highly abusive or neglectful environments may develop psychopathic traits as a survival mechanism. Researchers have found that children who grow up in violent or unstable homes often suppress emotional responses to cope with adversity. Making it more difficult to differentiate, “…adolescents often appear callous and narcissistic, sometimes to hide their own fear and anxiety” (Bartol, Bartol 2021). Over time, emotional detachment can evolve into lack of empathy type traits, making it difficult for them to also feel empathy or guilt.

Parenting, Trauma, and Aggression in Psychopathic Children

Research highlights the complicated interactions between parenting styles, trauma, and aggression in children with psychopathic traits. One study examined the impact of both positive and negative parental affect on child aggression. “Reactive aggression in children high on psychopathic traits appears less responsive to variations in either positive or negative parenting” (Yeh, Chen, Raine, Baker, Jacobson 2011).

· Reactive vs. Proactive Aggression: Children with psychopathic traits tend to show stable levels of reactive aggression regardless of their parents’ emotional warmth or harshness (Yeh, Chen, Raine, Baker, Jacobson 2011). However, proactive aggression—deliberate, reward/goal focused aggression—“was more strongly associated with negative parental affect in children with higher psychopathic traits” (Yeh, Chen, Raine, Baker, Jacobson 2011) .

· Resilience to Parenting: While most children become less aggressive with warm, supportive parenting, it is not well-known if youths with psychopathy can manipulate these parenting styles or if there is any positive progression at all (Yeh, Chen, Raine, Baker, Jacobson 2012). This suggests that traditional parenting interventions may not be as effective in curbing aggressive behavior in this population. Because of this, early intervention strategies should be used along with standard parenting techniques.

Emerging Treatment Strategies for Children with Psychopathic Traits

Even though it is difficult to treat psychopathy, new therapeutic methods show promising results, especially when they are used in adolescence.

· Reward-Based Behavioral Programs: Research has shown that individuals with CU traits are not responsive to punishment. Rather, they are more motivated by the use of incentives. The Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center (MJTC) in Wisconsin uses a reward system where the positive behaviors are rewarded and not the negative ones. Inmates are awarded items like Pokémon cards or pizza nights based on good behavior, a system aimed at cultivating cognitive empathy and social skills (NPR 2017).

· Cognitive Empathy Training: Although these children may never be able to feel others’ pain in the emotional way, they can be taught cognitive empathy (the ability to understand the impact of one’s actions on others) (NPR 2017). The goal of the therapists is to make children understand and repeat better social habits so that they can decrease their anti-social behavior.

These interventions provide a hopeful alternative to punishment based approaches, which often do not deter antisocial behavior in psychopathic children. There is growing support for the early recognition of psychopathic traits; not to label these children but to intervene before their behavior escalates.

A Need for Early Intervention and a Shift in Perspective

The study of child psychopathy presents both challenges and opportunities. While traditional parenting strategies and punishments often fail, new treatment models offer promising results by focusing on cognitive training, positive reinforcement, and neurological interventions. Understanding the complex relationship between trauma and psychopathy is essential to developing compassionate and effective treatment strategies.

Overall, these interventions offer a more optimistic option than the punitive measures which have the reverse effect of discouraging antisocial behavior in psychopathic children. By addressing the issue early, we can potentially steer these children on a better path, protect society, and provide them with the tools they need to interact with daily society successfully and safely.

References

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2021). Forensic Psychology and Criminal Behavior.

Hagerty, B., & Cornish, A. (2017, May 24). Scientists develop new treatment strategies for child psychopaths. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/05/24/529893128/scientists-develop-new-treatment-strategies-for-child-psychopaths

Lashbrook, A. (2021). There are no “child psychopaths” because we can’t diagnose them. yet. (vice). There Are No “Child Psychopaths” Because We Can’t Diagnose Them. Yet. (Vice) | Mechanisms of Disinhibition (MoD) Laboratory. https://modlab.yale.edu/news/there-are-no-child-psychopaths-because-we-cant-diagnose-them-yet-vice

Yang Y, Raine A, Narr KL, Colletti P, Toga AW. Localization of deformations within the amygdala in individuals with psychopathy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;66(9):986-94. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.110. PMID: 19736355; PMCID: PMC3192811.

Yeh, M. T., Chen, P., Raine, A., Baker, L. A., & Jacobson, K. C. (2011). Child psychopathic traits moderate relationships between parental affect and child aggression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3185247/

Theories of Crime and Why There is No One Size Fits All Theory (CJ 725)

Each theory of crime tries to explain why there is crime in our society. Some of the theories are specific whereas others are more broad. While they all have some similarities and differences, they generally share the same goal of explaining why crime exists. No theory is completely wrong because all of the theories offer answers from a different perspective. Crime can be caused by any number of reasons: “poverty, lack of opportunity, inadequate education, family dysfunction, peer pressure, mental health issues, and societal inequalities” (FBI - UCR, 2012). Looking at crime through more than one theory can explain more than looking at it through one single theory.

Two examples of theories of crime Our textbook defines Social Learning Theory as, “A theory of human behavior based on learning from watching others in the social environment. This leads to an individual's development of his or her perceptions, thoughts, expectancies, competencies, and values.” (Barton & Bartol, 2020). Another theory from our textbook is Strain Theory. Strain theory is defined as, “A prominent sociological explanation for crime based on Robert Merton’s theory that crime and delinquency occur when there is a perceived discrepancy between the materialistic values and goals cherished and held in high esteem by society and the availability of the legitimate means or reaching their goals.” (Barton & Bartol, 2020). Both of these theories present legitimate explanations for why there is crime. Someone growing up in a “rough area” may learn from a young age that crime is simply a part of life and something to be expected. In this situation, Social Learning Theory explains that someone simply does what they see their friends and or family doing. Strain Theory explains that someone who was laid off may need to steal food so that they won't starve. Also, someone with limited means may steal to gain items that are socially valuable but that they cannot afford. In both of these situations people commit crimes, but for different reasons. People may also commit crimes for several reasons, and the different reasons may be explained by different theories. Social Learning Theory and Strain Theory may both be helpful in understanding why individuals commit crimes.

I feel that these theories play into another related topic, the age-old question nature v nurture. Simply put for the context of this post, the question is: are people born bad (criminals), or are they born blank and learn their criminal behavior? In this debate, I generally fall on the side of nurture. Of course, there are exceptions to this belief, for example psychopaths, but they are the exception rather than the rule. The environment you are in shapes how you see the world and your role in it. If a person’s parents are criminals and in and out of jail, it is likely that the person will start to see that as just part of life and may very well follow in their parents’ footsteps. This of course may not happen and someone could grow up and realize that a life of crime is not best. In this case, no theory of crime would explain the behavior because there would be no criminal activity despite the factors that often lead people to commit crimes.

A trauma perspective is also helpful in looking at how these theories explain crime as a result of nurture or environment. A specific person’s environment or experiences may cause that person to experience trauma, which could result in mental illness and in some cases criminal behavior. However, groups of people can also experience community level trauma that can cause “damaged social relations/networks, elevation of destructive social norms, a low sense of collective political and social efficacy, and widespread sense of fear and shame.” (Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority). This trauma would help explain Social Learning Theory. Community level trauma can also result in “intergenerational poverty, long-term unemployment, business/job relocation, limited employment opportunities, and overall community disinvestment.” (ICJIA). Looking from the community level perspective, both Social Learning Theory and Strain Theory provide explanations for why some people in certain communities may turn to crime more often than in others.

There are so many theories because there is no one reason that people commit crimes. There are endless circumstances that may create criminal activity and intent and a theory to explain it. Crime is complex and there is no one single cause for it. The best understanding of crime must be based on an analysis looking at the problem from many different perspectives and using many different theories.

Citation:

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2020). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (12th ed.). Pearson Education.

“Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority.” ICJIA, ILLINOIS CRIMINAL JUSTICE INFORMATION AUTHORITY, 2020, icjia.illinois.gov/researchhub/articles/individual-and-community-trauma-individual-experiences-in-collective-environments.

“Variables Affecting Crime.” FBI - Uniform Crime Report, U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 5 Nov. 2012, ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2011/resources/variables-affecting-crime.

Book Review: “Trauma and Recovery” by Judith Herman

In Judith Herman’s seminal work on the study of pain and suffering, she explains the complexities of how trauma inserts itself into the brain’s function and daily life. The work was originally published in 1992 but has been updated with new findings as recently as 2022, to include conclusions made in the subject and partially inspired by the original publication. What’s most significant about this work to the subject of forensic behavioral analysis is its insights into how trauma “is an inherently political enterprise because it calls attention to the experience of oppressed people” (Herman, pg. 345), which aligns with the criminological theory that environment and circumstances are what’s behind an individual’s motivation to commit crime. This is how trauma can predict future criminal activity.

In one chapter, the connection between these two is especially clear: chapter five, which discusses child abuse. The book chronicles many victim accounts, and when grouped together like in this chapter, they present a whole image of what trauma does to the mind of people who face it, particularly children. Dissociation, social isolation, and mistrust of others are all common characteristics in the abused child, but one characteristic stands out as especially predictive of future criminal activity: “When it is impossible to avoid the reality of the abuse, the child must construct some system of meaning that justifies it” (Herman, pg. 150). As mentioned above, and exhibited in Herman’s description of the abused child, a prevailing theory for criminal behavior (“social learning theory”) is that we model what we observe in our environment and continue to let these behaviors exist in our environments when they go without punishment, allowing, for example, the continuous cycle of abuse and trauma to exist within generations of families (Rousseau, Module One).

Trauma, abuse specifically, can be detrimental to anybody, but is especially harmful for children who grow up in an abusive environment and aren’t aware that abuse is antisocial behavior. They develop a “malignant sense of inner badness [that] is often camouflaged by the abused child’s persistent attempts to be good. In the effort to placate the abusers, the child victim often becomes a superb performer” (Herman, pg. 154). This can develop into antisocial behavior in the child, since they aren’t aware of proactive ways of functioning in everyday life, which presents to those outside of the toxic environment as mentally ill behavior that is a product of the abuse. A child’s social environment, along with the cognitive impairment caused by the child’s own beliefs on what proactive behavior looks like, leads them to commit antisocial behavior. It should come as no surprise that nearly seventy percent of youth involved in the juvenile justice system show signs of mental illness/distress (Rousseau, Module Four).

To conclude the chapter, Herman explores how traumatized children grow into adulthood and how they cope with their memories of abuse. Though the possible generational trauma that may occur is persistent, Herman notices a different trend: many survivors go to great lengths to avoid treating others as they were treated. Many express fear and anxiety over their interpersonal relationships, and “as survivors attempt to [engage in] adult relationships, the psychological defenses formed in childhood become increasingly maladaptive” (Herman, pgs. 166-67). The conclusion that Herman comes to is that a changing perspective on trauma, and increased access to mental health resources, can help reduce the strain and impact that trauma may have on the mind and body. It’s clear while reading that the text is the foundation of our current understanding on the topic of trauma, along with being multifaceted in its application towards academic disciplines. Pain and suffering occur in everyone’s life, so by better understanding the effect of some of the most harmful forms of pain on a person’s daily function then we

References

Herman, J.L. (2022). “Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror.” Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Rousseau, D. (2025). “Forensic Behavioral Analysis: Module One.” Boston University.

Rousseau, D. (2025). “Forensic Behavioral Analysis: Module Four.” Boston University.

Trauma and Self-Care: A Clinical Mental Health Perspective

In the field of mental health counseling, trauma is an ever-present reality that shapes the lives of both clients and clinicians. Trauma can take many forms—chronic childhood adversity, acute incidents of violence, or systemic oppression—and its impact is profound, influencing cognition, emotions, and relationships. As a counselor, I see firsthand how unprocessed trauma manifests in anxiety, depression, and maladaptive coping mechanisms. While addressing trauma in clinical work is essential, the emotional toll on professionals in this field cannot be overlooked. This is where self-care becomes not just beneficial but necessary.

Self-care in mental health work is often misunderstood as an indulgence rather than a survival strategy. Burnout and secondary traumatic stress (STS) are common in counseling professions, as absorbing others' pain can lead to emotional exhaustion. To counter this, counselors must engage in intentional self-care practices that go beyond surface-level relaxation. This includes regular clinical supervision, where processing difficult cases prevents emotional overload, and peer support networks that provide a safe space to share experiences and mitigate feelings of isolation.

Mindfulness and self-compassion also play a significant role in mitigating the impact of trauma exposure. Research supports that mindfulness-based practices, such as grounding exercises and guided meditation, can help counselors regulate their own nervous systems, making them more present and effective for their clients. Setting boundaries, both emotionally and physically, is another crucial element of self-care. This means establishing realistic caseloads, taking necessary breaks, and allowing oneself to disconnect from work at the end of the day.

Ultimately, addressing trauma—whether in clients or within ourselves—requires a balanced approach that integrates professional support, mindful self-awareness, and structured self-care routines. In a field where helping others is the primary focus, ensuring our own well-being is equally critical. Sustainable mental health work depends on our ability to care for ourselves so we can continue to care for others.

Below, I've attached some resources for self-care that I highly recommend!

-

American Psychological Association (APA) - Self-Care for Psychologists

https://www.apa.org/careers/early-career/self-care- Offers guidance on managing stress, burnout, and emotional fatigue.

-

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) - Mental Health Self-Care

https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Individuals-with-Mental-Illness/Managing-Stress- Provides stress management techniques and self-care strategies.

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) - Trauma-Informed Self-Care

https://www.samhsa.gov/trauma-violence-types/self-care- Focuses on self-care practices for professionals dealing with trauma survivors.

-

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) - Self-Care for Providers

https://www.nctsn.org/resources/self-care-resources- Provides specific self-care tools for those working with trauma-exposed individuals.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) - Coping with Stress and Self-Care

https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/stress-coping/selfcare.htm- Discusses self-care techniques backed by public health research.

Gratitude Journaling: A Healing Strategy in the Criminal Justice Field

Dealing with trauma is inevitable in the criminal justice field. From those working on the ground to stop crime to those who deal directly with perpetrators of crime to the victims themselves, everyone within the system faces challenges that leave emotional scars on them. The effects of trauma may look differently from person to person but can lead to physical and mental exhaustion, a deep sense of disconnect from the world around you, or burnout, which has a host of negative effects in and of itself. Those working in this field may describe that it feels like they are carrying a massive weight on their shoulders to keep those around them safe. However, we can use simple tools to mitigate these feelings, including gratitude journaling.

Gratitude journaling is a practice of regularly writing down things that you are grateful for. Studies have shown this practice significantly promotes greater resilience, reduces stress, and improves overall mental health and well-being. By regularly focusing on the positive aspects of our lives, we can rewire our brains to counteract the effects of trauma in high-stress criminal justice professions (Weldon, 2020).

What this looks like

You’ll need a notebook and a few minutes each day, making this an accessible tool for just about everyone!

- Set aside time: Dedicate just a few minutes a day to write freely and uninterrupted.

- Be specific: Write at least three things you are grateful for. These can be rather simple.

- Focus on the present: Practice mindfulness by acknowledging what is happening in the present moment.

For those working in this field, the impact of trauma is an unfortunate reality but gratitude journaling is a simple, accessible tool for healing. While it can increase long-term well-being by about ten percent, it is important to note that this practice should not be used in place of professional mental health services, especially for individuals dealing with severe trauma (Penn State Health, n.d.). Regularly practicing gratitude for just a few minutes each day can complement, rather than replace, more comprehensive forms of healing.

References

Penn State Health. (n.d.). 10 amazing statistics to celebrate National Gratitude Month. Penn

State Health. Retrieved February 22, 2025, from https://prowellness.childrens.pennstatehealth.org/10-amazing-statistics-to-celebrate-national-gratitude-month/

Smith, L. (2022). Daily Gratitude Journaling Prompts [Photograph]. The Good Body. https://www.thegoodbody.com/wp-

content/uploads/2022/11/daily-gratitude-journal-prompts.jpg

Weldon, K. (2020, January 29). The neuroscience of gratitude and trauma. Psychology Today.

How Safe Is Our World Today, Really?

I have noticed increased vigilance amongst the population, increased reporting of crimes and headlines in newspapers, increased interest in true crime, crime documentaries/films, and a general public intoxication of crime. Why people have become so enamored with genres such as true crime, I don't think is necessarily a modern phenomenon -- I mean, take a look at the sheer popularity of Agatha Christie's books, with her first book being published in 1920 (Britannica, 2024).

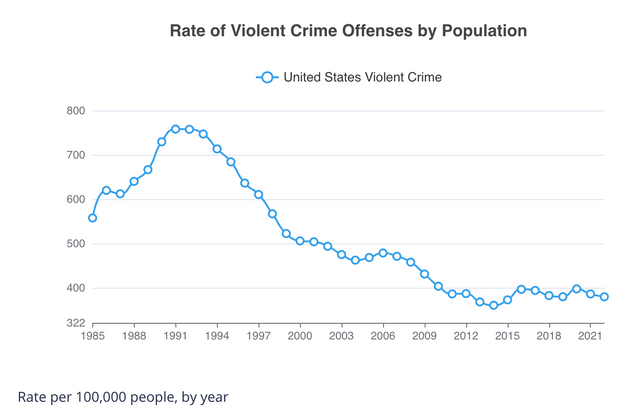

If we take a look at data from the FBI's Crime Data Explorer (https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend), we can see some really interesting things. For example, if we look at the rate of violent crime offenses by population (in the U.S.), we are met with data that suggests that 2022 is one of the "safest" years.

Despite these reassuring statistics, according to the Lloyd's Register Foundation World Risk Poll (2021), 39% of Americans surveyed feel less safe than they did five years ago. As well as that, 26% of Americans felt very worried about violent crime causing them serious harm, which was an increase from 22% in 2019. So, despite there being evidence from the FBI that 2021 and 2022 are significantly safer than other years, in regards to violent crime, individuals feel less safe compared to 5 years ago (2016), which was more unsafe than 2021. In 2016, the FBI reported there to have been a rate of 397.5 violent crime offenses per 100,000 compared to 387 in 2021.

So, even though the world is safer than it previously was, people still are more concerned about their safety. This feeling of unsafety could be a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which, for many individuals, led to long-term health consequences or mental health consequences. However, this perception gap (Ropeik, 2011) between the likelihood of violent crime and the perceived fear of violent crime existed long before the pandemic. Many individuals chalk this perception gap up to the media, the increased reporting of violent crimes, and the idea of "if it bleeds, it leads" - a term coined by William Randolph Hearst at the end of the 1890s.

Surveys such as the Figgie Report on Fear of Crime (Research and Forecasts Inc, 1980) suggest that the fear of crime was also pervasive in the late 70s/80s, with 4 out of 10 Americans being highly fearful of becoming victims of violent crime. However, as we can see from the FBI UCR data above, the 80s into the mid-90s was a time where the rate of violent crime offenses were significantly higher, meaning perhaps Americans' fear at the time was more based in true likelihood rather than perceived likelihood.

If we consider comparing violent crime to another type of crime, such as property crimes, we are met with starkly higher rates of offenses than that of violent crimes. All property crimes include arson, burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft, and all violent crimes include homicide, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. In 2022, the rate of property crime offenses was 1,954.4 per 100,000 people, compared to 380.7 per 100,000 people for violent crimes. Despite more offenses of property crime occurring per year in the United States, it is given less media attention. In Michael O'Hear's statistical overview of media coverage in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (2020), he compared the offenses noted on the front page of the Journal Sentinel and WTMJ.com to offenses reported to police in Wisconsin.

[Will try to re-insert media; had issues trying to attach the pie charts]

Theft and burglary accounted for 62% of the crimes reported in Milwaukee County and 68% statewide. This starkly contrasts the reporting of these two crimes, accounting only for 3% of the Journal Sentinel stories and 22% of the stories reported on WTMJ.com. O'Hear also made an interesting realization that the media placed a stronger emphasis on crime with female victims and young victims, which, according to the data relating to homicide victims in Milwaukee, was disproportionate to the actual patterns.

Works Cited

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, February 16). Agatha Christie. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Agatha-Christie

FBI Crime Data Explorer, UCR https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend

Lloyd's Register Foundation. (2021). World Risk Poll, Gallup Data. Retrieved from https://wrp.lrfoundation.org.uk/a-world-of-risk-country-overviews-2021/

Ropeik, D. (2011, February 3). The perception gap: An explanation for why people maintain irrational fears. Scientific American Blog Network. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/the-perception-gap-an-explanation-for-why-people-maintain-irrational-fears/

Research and Forecasts Inc. (1980) Figgie Report on Fear of Crime - America Afraid, Part One - The General Public. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/figgie-report-fear-crime-america-afraid-part-one-general-public

Michael O'Hear, Violent Crime And Media Coverage In One City: A Statistical Snapshot, 103 Marq. L. Rev. 1007 (2020).

Available at: https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol103/iss3/14