CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

Book Review: “Know My Name: A Memoir” by Chanel Miller

“My name is Chanel. I am a victim, I have no qualms with this world, only with the idea that it is all that I am.” (Miller, 2019).

In January 2015, Chanel Miller was sexually assaulted behind a dumpster near a fraternity on Stanford University’s campus. Miller woke up in a hospital with no recollection of the event and was given little to no explanation of what had happened. It wasn’t until she came across a news headline stating that a man named Brock Turner had been caught sexually assaulting an unconscious, intoxicated woman. Miller began to piece together that she was the woman in the headline and discovered the details of her own sexual assault at the same time as the rest of the world.

Turner was initially charged with five felony counts: rape of an intoxicated person, rape of an unconscious person, sexual penetration by a foreign object of an unconscious woman, and assault with intent to commit rape (Miller, 2019). Had he been convicted on all counts, he would have faced a maximum prison sentence of 10 years and would have been required to register as a sex offender (Knowles, 2016). However, the five felony counts were reduced to three and Turner was sentenced to six months in county jail, serving only three months before his release.

During the trial, Miller was publicly known as “Emily Doe” to protect her identity. She wrote an impact statement in the sentencing phase of the trial, which was later published on BuzzFeed (with her permission) with her name replaced as “Emily Doe”. The 7,000-word statement immediately went viral and was viewed by fifteen million people within the span of a week (Liu, 2019). Miller’s statement led to changes in California state law resulting in more stringent sexual assault sentences and also contributed to the recall of Judge Aaron Persky from the bench (BBC, 2019).

“Writing is the way I process the world.” (Miller, 2019, p. 315). This poignant memoir explores trauma, healing, and resilience, as Miller reflects on the culture surrounding sexual assault and how the criminal justice system treats individuals who have experienced sexual assault. "If they explained what I was consenting to, it was lost on me. Papers and papers, all different colors, light purple, yellow, tangerine. No one explained why my underwear was gone, why my hands were bleeding, why my hair was dirty, why I was dressed in funny pants, but things seemed to be moving right along, and I figured if I kept signing and nodding, I would come out of this place cleaned up and set right again." (Miller, 2019, p. 9). Although the Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) kit is one of the most effective tools for convicting a perpetrator of rape, it can also be one of the most traumatizing experiences for survivors to endure (Rousseau, 2025).

In her memoir, Miller reclaims her identity and gives silenced voices recognition, “The saddest things about these cases, beyond the crimes themselves, are the degrading things the victim begins to believe about her being. My hope is to undo these beliefs. I say her, but whether you are a man, transgender, gender-nonconforming, however you choose to identify and exist in this world, if your life has been touched by sexual violence, I seek to protect you.” (Miller, 2019). I first read this memoir on November 6, 2021, and although I have only read it once, its impact will stay with me forever.

References:

BBC. (2019). Stanford Sexual Assault: Chanel Miller reveals her identity. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-49583310

Liu, R. (2019). Know My Name by Chanel Miller review – memoir of a sexual assault. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/sep/25/know-my-name-by-chanel-miller-review

Miller, C. (2019). Know my name: a memoir. [New York], Viking.

Knowles, H. (2016). Brock Turner found guilty on three felony counts. The Stanford Daily. https://stanforddaily.com/2016/03/30/brock-turner-found-guilty-on-three-felony-counts/

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 5: Special Populations. Online Class. Boston University Metropolitan College. https://alt-5deff46c33361.blackboard.com/bbcswebdav/courses/25sprgmetcj725_o1/course/w5/metcj725_ALL_W5.html?one_hash=972FE4B49A4CDD2D8DC867520B1C2BA6&f_hash=DA6451E61222D56A8F5BFA4FED95064B

Breaking the silence: Liza Long’s Journey from Stigma to Advocacy

Breaking the Silence: Liza Long’s Journey from Stigma to Advocacy

On the morning of December 14, 2012, 20-year-old Adam Lanza shot and killed twenty children and six adult staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, before taking his own life. Later that day, investigators found Adam Lanza’s first victim, his mother Nancy Lanza, whom he had shot four times prior to leaving for the school.

As the nation processed the tragedy, it came to light that, at different times, Adam had been diagnosed with anxiety, sensoryintegration disorder, autism spectrum disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and it was suspected that he had schizophrenia (ABC News, 2014; Breslow, 2013; Engel, 2014). It also became clear that, despite his parents’ multiple attempts to diagnose and treat his condition, they were unable to find the medications and support systems that would be effective.

An Anonymous Blogger

Meanwhile, in Boise, Idaho, a mother of four was going through a diagnosis and treatment ordeal with her 13-year-old son. Two days before the Sandy Hook shooting, her son – let’s call him Michael – had been placed in an acute mental hospital after a violent outburst that included yelling, punching, biting, and threats of suicide. In her anonymous blog, The Anarchist Soccer Mom, she opened up about Michael’s threatening behavior, the emotional toll it had taken on her and her other children, and the impossible choices that lay ahead (Long, 2012).

Titled “I Am Adam Lanza’s Mother,” the post described “years of missed diagnoses, ineffective medications, and costly therapies” (Long, 2015, p. 14), expressing the author’s greatest fear: that one day she would find herself in Nancy Lanza’s shoes. Initially shared on Facebook, the post received praise for its honesty, and soon a friend urged the blogger to publish the piece under her real name. “Until people start putting their names on these stories, they aren’t real,” he explained (Long, 2015, p. 15).

The Price of Speaking Up – and The Price of Silence

The blogger’s name was Liza Long, and her cry for help was heard and shared by millions of people, leaving many to wonder what happened next.

To start, Michael’s estranged father read the post to the boy overthe phone while he was still hospitalized. Then, the man used the essay as evidence to take away Long’s custody of their two younger children until Michael was institutionalized. Thusbegins Long’s book, The Price of Silence: A Mom’s Perspective on Mental Illness, published three years after these events.

The book is written for two primary audiences: those who have a family member with a mental illness and understand itscomplexities and challenges – and those who may not realize how pervasive mental illness is and whose first inclination mightbe to keep it quiet. “I hope you’ll look at that child acting out on the playground or in the classroom with different, more compassionate eyes,” the author explains (Long, 2015, p. 193).

One could argue that a third audience for this book was always Long herself. Written in a reflective, journal-like style, revisiting many events over and over again, the book appears to be a way for Long to process the preceding three years, organize her thoughts, and find strength by connecting with her readers.

Overcoming the Stigma and Searching for Answers

Throughout the book, the stigma of mental illness takes many forms: from self-stigma, which leads parents to blame themselves for their child’s illness, to social stigma, encounteredin stores, churches, and schools. Long (2015) argues that self-stigma is the hardest to overcome, as parents “are more than willing to blame themselves, and society at large is happy to reinforce that message” (p. 15). She realizes that her initial choice to blog anonymously was driven by self-stigma and that facing it and openly discussing mental illness was a necessary step toward finding effective treatment.

In the course of the book, Michael, much like Adam Lanza,cycles through multiple diagnoses: intermittent explosive disorder; oppositional defiant disorder; pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified; Asperger’s syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Long (2015) observes that this “circuitous journey through the Wonderful World of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders […] is pretty typical for children with mental disorders” (p. 103). She applies all her skills as a scholar and her dedication as a mother to researching the science behind these disorders and the available treatment options. After consulting numerous specialists, she finally arrives at a definitive diagnosis for Michael – juvenile bipolar disorder – and confirms that lithium is effective in controlling it.

The Legacy of “I Am Adam Lanza’s Mother”

Just like the original essay, the book has led to even more unmasking. Following its release, the public learned that Michael’s real name was Eric and that, by then, he was considering his college options (Arnold-Ratliff, 2016). Long’s appearances on television, new publications, and congressional testimony have made her a well-known mental health advocate.

Using her authentic voice – and her real name – Long has helped make the experiences of families dealing with mental illness more relatable and, therefore, more real for millions of people. It is safe to say that Long will never be in Nancy Lanza’s position– and through her advocacy, she has helped many other families avoid feeling that way as well.

References

Arnold-Ratliff, K. (2016, September 18). Liza Long - “I Am Adam Lanza’s Mother” Essay. Oprah.com. https://www.oprah.com/inspiration/liza-long-i-am-adam-lanzas-mother-essay

Long, L. (2012, December 16). “I Am Adam Lanza’s Mother.”HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/i-am-adam-lanzas-mother-mental-illness-conversation_n_2311009

Long, L. (2015). The Price of Silence: A Mom’s Perspective on Mental Illness. A Plume Book.

Montaldo, C. (2004, July 21). Mass Murderers, Spree and Serial Killers. ThoughtCo; ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/defining-mass-spree-and-serial-killers-973123

Rousseau, D. (2025). Lecture Notes from Module 6: The Psychology of Hate and Fear. In Retrieved from Blackboard. Boston University MET CJ-725.

The Intersection of Trauma, Psychology, and Sexual Offending: Implications for Criminal Justice

Human behavior is shaped by trauma, which impacts both mental health and criminal behavior. In forensic psychology research, trauma is frequently studied in victim contexts yet holds substantial significance for offender behavior, especially among psychopaths and sexual criminals. Understanding how trauma interplays with these criminal behaviors can help inform risk assessments, treatment approaches, and policy interventions within the criminal justice system (Smithwick, Lecture Notes: Module 4 lecture notes).

Exposure to early-life trauma, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect, may lead to the development of psychopathy and sexual offending behaviors, according to research findings (Van der Kolk, 2014). Research shows that many violent offenders experienced childhood maltreatment, according to Widom's study (1989). Additionally, system-induced trauma, such as that experienced in the juvenile justice system (Smithwick, Lecture Notes: Module 4), can exacerbate maladaptive behaviors. Popular culture misuses the term "psychopath," leading to offender stigmatization, which complicates rehabilitation efforts (Lecture Notes: Psychopathy and Group Projects). Trauma functions as a risk factor for criminal behavior, but it does not guarantee the development of psychopathy or sexual offending. The combination of trauma with genetic elements and environmental influences alongside neurobiological components determines the behavioral path of individuals (Gao et al., 2010).

Psychopathic individuals display characteristics such as an absence of empathy alongside superficial charm and manipulative behaviors. According to traditional views, psychopaths possess emotional detachment, which protects them from any trauma effects. New scientific studies dispute previous beliefs by demonstrating that psychopathic behaviors could actually originate from adverse reactions to childhood trauma (Porter, 1996). The case of Khalif Browder, who experienced severe system-induced trauma while detained at Rikers Jail, Lynn Smithwick, in the Lecture Notes for Module 4, illustrates how deeply their traumatic experiences can impact youth. The Psychopathy Checklist (PCLR) development by Dr. Robert Hare has made significant advances in our understanding of psychopathy as a disorder (Lecture Notes: Psychopathy and Group Projects). Primary psychopaths have natural emotional deficiencies that prevent any reaction to trauma (Kiehl, 2006), while secondary psychopaths demonstrate increased impulsivity and emotional instability related to traumatic childhood experiences (Skeem et al., 2007). Forensic and correctional settings require understanding this distinction because secondary psychopaths can benefit from trauma-based interventions, but primary psychopaths do not benefit from standard therapeutic methods.

Research by Seto & Lalumière (2010) shows that many sexual offenders endured traumatic events in their youth, including sexual or physical abuse. The abuse-to-offender cycle theory emerged from studies indicating that people who suffer sexual victimization during their lifetime could become future sexual offenders (Jespersen et al., 2009). In the case of Abby, a youth who experienced complex trauma from trafficking, Lynn Smithwick, in the Lecture Notes for Module 4, emphasizes how childhood trauma effects persist into adulthood and why trauma-informed care is essential. Using trauma-informed and person-centered language is essential to reduce stigma and deliver proper treatment to sexual violence offenders (Lecture Notes: Psychopathy and Group Projects). Criminal actions remain unjustifiable although their existence emphasizes the vital role of trauma-informed methods for prevention and rehabilitation efforts.

Correctional settings need to integrate trauma-informed care (TIC) because trauma significantly influences offending behavior. The principles of Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) include identifying past trauma in offenders and preventing re-traumatization during incarceration or therapeutic interventions while deploying evidence-based therapeutic practices such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and mindfulness-based treatments (Ford et al., 2013). However, treating offenders—particularly psychopathic individuals—poses unique challenges. The ineffectiveness of conventional rehabilitation approaches with psychopathic individuals prompts experts to consider behavioral management as a more appropriate treatment focus. Standard treatments have the potential to intensify psychopathic behaviors because these individuals naturally exhibit manipulation and deceit (Lecture Notes: Psychopathy and Group Projects). Targeting impulsivity and risk assessment through interventions could help reduce harmful behaviors according to Harris & Rice (2006).

Different demographics experience trauma and its effects in varying ways. According to Bryant-Davis (2019) racial identity combined with socioeconomic status and cultural background dictate both trauma exposure rates and mental health service availability. Research conducted on juvenile detention populations in Chicago and Cook County shows widespread trauma and mental health problems among inmates which requires better PTSD screening and specialized therapeutic interventions (Smithwick, Lecture Notes: Module 4). The success of interventions in criminal justice settings depends on cultural competency to effectively serve diverse populations. Providers require training to identify how different cultures respond to trauma and adjust treatment to match these responses.

To address trauma effectively in at-risk individuals we need a comprehensive multi-faceted approach. Schools and juvenile justice programs together with social services must launch early intervention programs to keep high-risk youth from becoming part of the criminal justice system (Felitti et al., 1998). Assessment approaches for sexual offenders and psychopathic individuals require trauma history integration to customize treatment recommendations (Andrews & Bonta, 2010). Prison rehabilitation programs should adopt trauma-informed care methods to address how trauma influences criminal behavior while continuing to enforce accountability (Miller & Najavits, 2012). High-risk offenders should receive trauma-focused mental health services through reentry programs as part of their post-release support to lower the chances of recidivism (Lösel & Schmucker, 2005).

Forensic psychology requires an understanding of trauma's connection to psychopathy and sexual offending to create more successful treatment methods. Although rehabilitation isn't possible for every offender, adopting a trauma-informed approach will lead to lower rates of recidivism and enhance criminal justice system outcomes. A comprehensive approach that addresses trauma at personal and institutional levels provides a compassionate and research-supported way to prevent crime and rehabilitate offenders.

References:

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct. Routledge.

Bryant-Davis, T. (2019). Thriving in the wake of trauma: A multicultural guide. Praeger.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

Ford, J. D., Kerig, P. K., & Olafson, E. (2013). Treating traumatized children: Risk, resilience, and recovery. Routledge.

Gao, Y., Glenn, A. L., Schug, R. A., Yang, Y., & Raine, A. (2010). The neurobiology of psychopathy: A neurodevelopmental perspective. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(12), 813-823.

Harris, G. T., & Rice, M. E. (2006). Treatment of psychopathy: A review of empirical findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(7), 1027-1047.

Jespersen, A. F., Lalumière, M. L., & Seto, M. C. (2009). Sexual abuse history among adult sex offenders and non-sex offenders: A meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(3), 179-192.

Kiehl, K. A. (2006). A cognitive neuroscience perspective on psychopathy: Evidence for paralimbic system dysfunction. Psychiatry Research, 142(2-3), 107-128.

Lösel, F., & Schmucker, M. (2005). The effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1(1), 117-146.

Miller, N. A., & Najavits, L. M. (2012). Creating trauma-informed correctional care: A balance of goals and environment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1), 17246.

Porter, S. (1996). Without conscience or without active conscience? The etiology of psychopathy revisited. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1(2), 179-189.

Seto, M. C., & Lalumière, M. L. (2010). What is so special about male adolescent sexual offending? A review and test of explanations through meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(4), 526-575.

Skeem, J. L., Polaschek, D. L. L., Patrick, C. J., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2007). Psychopathic personality: Bridging the gap between scientific evidence and public policy. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(3), 95-162.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Widom, C. S. (1989). The cycle of violence. Science, 244(4901), 160-166.

Module 4 Notes. Boston University.

Lecture Notes: Psychopathy and Group Projects. Boston University.

Trauma and Forensic Evaluation

An article by Goldenson, Brodsky, and Perlin, discusses the role of trauma regarding the process of the forensic evaluation. The authors discuss the various roles in the process and how trauma can impact their experiences. They delve into the evaluators and their role, discussing the parameters of their processes to maintain a high ethical standard and the integrity of their work. In discussing the role of empathy, a substantial factor in the evaluation process, the authors state that, “Here, we hold that empathy and objectivity are not mutually exclusive, that conveying empathy is not just reserved for psychotherapy, and that experiencing empathy for the examinee is not inherently a form of deception or bias” (Goldenson et al., 2022, p. 229). They note the potential effectiveness of empathy as long as it is utilized properly and professionally. It allows for the examiner to build a better working relationship with the client and allows a more productive space for information to be given. The authors discuss the limitations of using empathy as well, stating that, “FMHEs are tasked, then, with striking a delicate balance between experiencing and conveying sufficient empathy while maintaining sufficient distance, restraint, and boundaries” (p. 230). This further reinforces the importance of boundaries in such a professional relationship, and how strenuous it can be for the evaluator to balance normal emotional responses with the neutrality required from evaluators.

Another point of discussion the authors touch on is the evaluators own experiences with trauma. As professionals in a field riddled with traumatic experiences, often dealing with their own traumatic experiences, the weight of such heavy topics can have a negative impact on evaluators. A solution to this issue that the authors mention is that, “The very human potential for emotional reactivity highlights the importance of a FMHE having self-awareness, insight, and resolution related to their own history of adversity or vicarious trauma in order to manage the tensions that arise in evaluating examinees with trauma histories” (p. 230). Dealing with that trauma, especially as a career, can be incredibly overwhelming, and the authors highlight the importance of reflection with evaluators so that they can adequately cope with the stressors. The reflection is also important to providing the best work for the individuals being evaluated. Being aware of one’s own trauma, and trauma information in general, also leads to more effective client interactions. This is highlighted when the authors mention that, “A trauma-informed approach does mean that the evaluator needs to attend carefully to the research on complex trauma and its potential influence on psychometric tests” (p. 231). Trauma can affect numerous aspects of the evaluation process, so it is imperative for key players to be aware of the ways trauma can manifest. The main concept of the article is effectively stated by the authors highlighting that, “Adopting trauma-informed practices not only may afford examinees dignity and respect, but also will likely improve the quality of forensic mental health assessment” (p. 234). Education and awareness of trauma is beneficial to every role in the criminal justice system as it can strengthen and improve the criminal justice process.

References

Goldenson, J., Brodsky, S. L., & Perlin, M. L. (2022). Trauma-informed forensic mental health assessment: Practical implications, ethical tensions, and alignment with therapeutic jurisprudence principles. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 28(2), 226-239. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000339

The Role of Trauma-Informed Care for Women in the Criminal Justice System

A background of trauma frequently affects women in the criminal justice system, profoundly influencing their experiences. Their paths into crime are often linked to survival strategies resulting from poverty, abuse, and mental health issues like depression and PTSD (Rousseau, 2025). However, many traditional treatment programs have ignored the crucial role trauma plays in women’s offending by using a one-size-fits-all strategy based on models created for men. This blog post will discuss the significance of gender-responsive, trauma-informed therapeutic approaches for women in the court system. Addressing the close relationship between trauma and criminal conduct is crucial for supporting recovery, rehabilitation, and long-term success. Research has consistently shown that women often enter the system as a result of trauma and socio-economic disadvantage. For many, their offences are intertwined with coping mechanisms for dealing with the long-term effects of victimization (Rousseau, 2025). Substance misuse may be a way to self-medicate, while offences like theft or fraud can arise out of economic desperation. Without addressing these underlying factors, traditional approaches risk perpetuating cycles of trauma and criminal behaviour.

Unlike conventional methods, trauma-informed practices are intentionally gender-responsive, addressing the specific needs and vulnerabilities of women. The development of trauma-informed approaches is grounded in feminist theories of ‘complex trauma’, which recognizes trauma as a prolonged experience of abuse and adversity, often within intimate or familial relationships (Petrillo, 2021). In the UK, trauma-informed practice in women’s prisons draws heavily on Stephanie Covington and Barbara Bloom’s work on gender-specific interventions, which are based on creating safe, respectful, and dignified environments while addressing substance misuse, trauma, and mental health issues through integrated, culturally relevant services (Petrillo, 2021). This allows women dealing with trauma to heal in a supportive environment that acknowledges their unique experiences, fostering resilience and reducing the likelihood of reoffending (Petrillo, 2021). Trauma-informed practices create a foundation for meaningful rehabilitation and personal growth by prioritizing safety, empowerment, and respect. While therapies such as dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), traumatic incident reduction (TIR), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and relaxation techniques have been used to treat incarcerated women with trauma histories, these interventions are not always designed specifically to address trauma in this population and often require a highly trained clinician or staff to implement effectively (King, 2017). While it may be more feasible for previously incarcerated women to access such specialized care post-release, it is much more difficult to provide within the prison setting. Therefore, it is crucial to consider how prison life itself can be improved for women, not just how to support their reintegration once they are released. This is why it is important to have several trauma-informed interventions developed specifically for women in prison, like Seeking Safety, Helping Women Recover/Beyond Trauma, and Beyond Violence (King, 2017).

Although trauma-informed practices have become more popular recently, you may contend that they might not be scalable in large, underfunded and overcrowded jail systems with little access to highly qualified medical professionals. This poses an important question regarding the viability of broad distribution in the absence of sufficient resources and staff. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that although trauma-informed care provides a sympathetic response to women's particular experiences, the legal system itself frequently adopts gender-specific methods slowly, which can result in uneven implementation among institutions. We must think about systemic changes that prioritize trauma-informed techniques and enhance general prison conditions if we are to effectively close these gaps. This could entail promoting policy changes, providing post-release continuity of care, and educating general staff on trauma-informed practices.

References:

King, E. A. (2017). Outcomes of Trauma-Informed Interventions for Incarcerated Women: A Review. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(6), 667-688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15603082

Petrillo, M. (2021). ‘We've all got a big story’: Experiences of a trauma‐informed intervention in prison. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 60(2), 232-250.

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Childhood Trauma & Criminality: How Public Safety and Support Systems Fail Vulnerable Youth

Child abuse is a national safety crisis, with 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the United States being said to experience some kind of child abuse, whether that be physical, emotional, sexual abuse or neglect (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.). The consequences of childhood abuse and trauma have been researched extensively across field of social sciences, psychology, developmental neuroscience and more, as society has begun to realise to extent to which these traumatic experiences in childhood can influence later behaviour and mental health issues. In recent years, studies have examined the rippling effects childhood trauma can have on victims even decades after the victimisation, evidencing how trauma can hinder work success (Paulise, 2023), can detrimentally affect romantic relationships and marital success (Nguyen et al., 2017) and is significantly associated with varying chronic health problems (Afifi et al., 2016). The effects of childhood abuse are unbounded.

Child abuse is a national safety crisis, with 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the United States being said to experience some kind of child abuse, whether that be physical, emotional, sexual abuse or neglect (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.). The consequences of childhood abuse and trauma have been researched extensively across field of social sciences, psychology, developmental neuroscience and more, as society has begun to realise to extent to which these traumatic experiences in childhood can influence later behaviour and mental health issues. In recent years, studies have examined the rippling effects childhood trauma can have on victims even decades after the victimisation, evidencing how trauma can hinder work success (Paulise, 2023), can detrimentally affect romantic relationships and marital success (Nguyen et al., 2017) and is significantly associated with varying chronic health problems (Afifi et al., 2016). The effects of childhood abuse are unbounded.

Criminality and childhood victimisation

Though childhood abuse is a hard to measure hidden phenomenon, the statistics we do have show that children who experience abuse, neglect, or exposure to violence are at higher risk of engaging in criminal activity later in life.

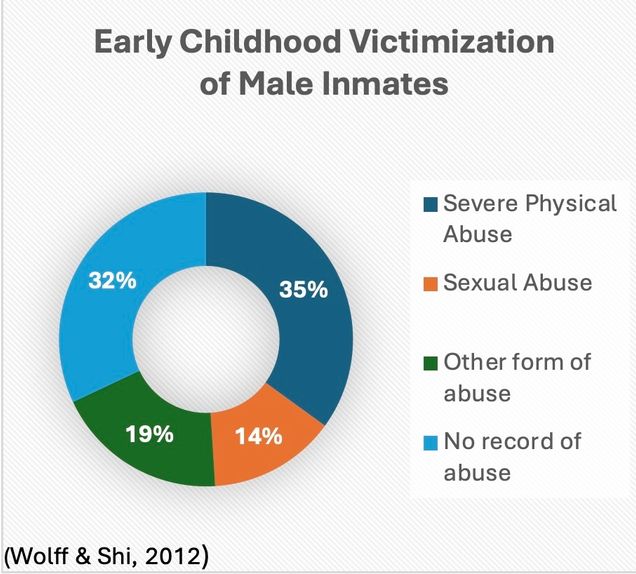

In the U.S., studies have reported as many as 1/6 male inmates having experiences physical or sexual abuse before the age of 18 (Wolff & Shi, 2012) – and this is the low end of the scale. Other studies, such as one by Robin Weeks and Cathy Spatz Widom (1998) for the National Institute of Justice found 68% of the male inmates in their sample reported some form of childhood abuse before the age of 12 (physical, sexual, neglect). Scholars have theorised this is linked to the Cycles of Violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989; Widom & Maxfield, 2001), which claims that adverse childhood experiences of violence, abuse or neglect can cause victims to reproduce this behaviour in their adult lives which often leads to violent criminal behaviour.

In the U.S., studies have reported as many as 1/6 male inmates having experiences physical or sexual abuse before the age of 18 (Wolff & Shi, 2012) – and this is the low end of the scale. Other studies, such as one by Robin Weeks and Cathy Spatz Widom (1998) for the National Institute of Justice found 68% of the male inmates in their sample reported some form of childhood abuse before the age of 12 (physical, sexual, neglect). Scholars have theorised this is linked to the Cycles of Violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989; Widom & Maxfield, 2001), which claims that adverse childhood experiences of violence, abuse or neglect can cause victims to reproduce this behaviour in their adult lives which often leads to violent criminal behaviour.

However, I challenge this idea. Instead, I theorise that childhood victimisation of violence itself does not inherently cause more violence, instead it is the experience of violence within a society that fails to protect, support, or care for vulnerable children that fosters these cycles. This phenomenon should be understood through a lens similar to the social disability model: just as disability does not inherently limit a person, but rather society’s failure to provide adequate support does, it is not abuse alone that leads to violence or criminality. Rather, it is the failure of social systems to intervene, protect, and care for trauma-affected children that perpetuates these outcomes.

Systemic Failures and Their Consequences

When we examine the systems in place to both prevent incidents of child abuse and promote healing among known victims, we can see failures of the system to adequately do so at every step of the way. Many politicians and academics defend these failures by using the hidden nature of abuse as an excuse – but research shows there were an estimated 558,899 instances of recorded child abuse in the US in 2022 alone (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.), thus proving there are countless cases that are known and in need of assistance. But what are the systems in place to support these children? And if they are working, why do we see so many past victims of abuse spiral into criminality?

In my opinion, this is because of three main failures of policy and support services:

- Lack of Access to Mental Health Care: Many children in abusive environments do not receive the psychological care needed to process their trauma, leading to behavioural issues that escalate over time through exacerbation and development of mental health issues caused by lack of appropriate intervention and support.

- Underfunded Social Services: Child welfare systems often fail to provide consistent, long-term support, leaving many children vulnerable. Increased funding and allocation of resources could in the long-term prevent increased criminality among this population, and instead help more victims heal and become citizens who contribute positively to society.

- School and Community Gaps: Schools and communities frequently lack the resources to identify and assist trauma-affected children before they enter the criminal justice system. Training should be compulsory for teachers and community workers to help them identify signs of trauma, and to intervene in trauma-informed ways that benefit the child without retraumatizing them.

Breaking the Cycle: What Can Be Done?

To break the ‘cycle of violence’ and criminality associated with childhood trauma, we must shift our focus from reactive to proactive solutions, by working to ensure that abuse survivors receive the support they need to heal and thrive. This calls for a multi-faceted reformative approach to support procedures and legislative prevention policies, that refocuses its aim to break the socially imposed link between childhood victimisation of violence and adult or adolescent criminality.

- Expanding Trauma-Informed Care must become a priority across a vast range of public systems including child welfare, education, and criminal justice systems. This involves comprehensively training teachers, social workers, law enforcement, and healthcare providers to recognise signs of trauma, and to deal with these situations in ways that do not retraumatise children.

Strengthening Family and Community Support Systems should also be a priority. Government funding should be re-allocated to promote evidence-based programs that target risk-factors for child abuse and have proven to reduce instances of violence. For instance, the program SafeCare which visits parents at home to help promote positive and safe relationships between caregivers and children.

Strengthening Family and Community Support Systems should also be a priority. Government funding should be re-allocated to promote evidence-based programs that target risk-factors for child abuse and have proven to reduce instances of violence. For instance, the program SafeCare which visits parents at home to help promote positive and safe relationships between caregivers and children.- Reforming the Juvenile Justice System would also help to aid trauma-affected youth in a real way instead of simply criminalising them. This could be done through diversion programs that connect with trauma-affected youth who may have encountered the criminal justice system. But instead of providing them with punishment, programs could be focussed on counselling efforts, and mental health support to address the root cause of early criminal behaviour.

- Improving Accessibility to Mental Health Resources would be a vital part of this process. Many trauma survivors - particularly those from marginalized communities - face significant barriers to receiving psychological care, especially in a nation lacking universal healthcare. Instead, systems could be put into place to provide victims with this care through community-based organizations and clinics, or even school based mental health programs – to ensure that children without access to health insurance and adequate health care can still access the tools they need to heal.

- Advocating for Policy Change would work to address systematic failures that prevent the prioritisation of child welfare. This could include allocating more funding for child protective services, improving foster care monitoring systems, and enforcing stricter measures for cases of institutional negligence. By shifting legislative priorities towards prevention and rehabilitation rather than punishment, we can begin dismantling the structural barriers that perpetuate cycles of trauma and criminality.

By addressing the root causes of violent behaviour through trauma-informed care and providing survivors with the tools they need to heal, we can create a future where childhood victimization of violence does not dictate one’s path in life.

Reference list:

Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M., Cheung, K., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., & Sareen, J. (2016). Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health reports, 27(3), 10–18. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26983007/

National Children’s Alliance. (n.d.). National Statistics on Child Abuse. https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/media-room/national-statistics-on-child-abuse/

Nguyen, T. P., Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2017). Childhood abuse and later marital outcomes: Do partner characteristics moderate the association? Journal of family psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 31(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000208

Paulise, L. (2023, June 9). 3 Ways Childhood Traumas Impact Work Productivity and Well-Being. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lucianapaulise/2023/06/09/3-ways-childhood-traumas-impact-work-productivity-and-well-being/

Weeks, R., & Widom, C.S. (1998). Early Childhood Victimization Among Incarcerated Adult Male Felons. National Institute of Justice: Research Preview, U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/fs000204.pdf

Widom, C. S. (1989). The Cycle of Violence. Science, 244(4901), 160–166. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1702789

Widom, C.S., & Maxfield, M.G. (2001). An Update on the “Cycle of Violence”. National Institute of Justice: Research Preview, U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/184894.pdf

Wolff, N., & Shi, J. (2012). Childhood and adult trauma experiences of incarcerated persons and their relationship to adult behavioral health problems and treatment. International journal of environmental research and public health, 9(5), 1908–1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9051908

Breaking the Chains of Trauma: A Look at Incarcerated Women

The criminal justice system, as it is currently structured, often overlooks the particular needs of incarcerated women, perpetuating a cycle of victimization and imprisonment. Unlike their male counterparts, many women enter the system not driven by the pursuit of power or financial gain but as a result of survival-related crimes—offenses rooted in abuse, extreme poverty, and substance dependence. When dealing with female offenders, we should treat them differently than male offenders, because "It is crucial to recognize that men and women have different needs and experiences, meaning that treatments should be equitable, but not necessarily equal" (Rousseau, 2025). Women's realities demands a fundamental shift in how we approach their rehabilitation, recognizing and addressing the different traumas that permeate their lives.

Trauma is not the exception; it is the norm. A significant number of these women have experienced physical, sexual, and emotional abuse throughout their lives, often beginning in childhood. Additionally, many are the primary caregivers for their children, which exacerbates their vulnerability and the consequences of their incarceration. This background of trauma profoundly impacts their mental health and well-being, increasing the risk of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other mental health challenges.

Stephanie Covington (2007) highlights how traditional correctional policies often fail to address the unique needs of women, reinforcing a system that punishes them for the very experiences that led to their incarceration in the first place. Instead, Covington advocates for relational and trauma-informed interventions that address victimization, caregiving roles, and mental health concerns. Gender-responsive programs provide an opportunity for comprehensive rehabilitation, improving reintegration and reducing recidivism.

But how does this translate into practice? First, it is crucial to build trust between incarcerated women and mental health professionals. This can be achieved through staff training on the prevalence and impact of trauma, as well as the implementation of peer support programs that foster a sense of community and mutual understanding.

Additionally, treatment programs must be specifically designed to address the unique needs of women who have experienced trauma. These programs should offer; individual and group therapy focused on trauma, substance abuse treatment, development of social and emotional skills, parenting support and family reunification assistance, and the promotion of physical and emotional safety, allowing women to process their traumatic experiences in a supportive environment.

Post-release programs are also essential. Mental health and addiction treatment, PTSD and co-occurring disorder therapy, as well as social skills development and emotional support, are critical components of effective rehabilitation efforts.

By prioritizing relational and trauma-informed interventions, the criminal justice system can begin to address the unique needs of incarcerated women, fostering healing and successful reintegration into society. Breaking the chains of trauma can pave the way toward a more just and equitable future for all incarcerated women, regardless of their past.

References:

- MET CJ 725 O1 Forensic Behavior Analysis. Spring 1, 2025, BU, Prof. Rousseau, D.

- Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2007). Risk-Need-Responsivity Model for Offender Assessment and Rehabilitation.

- Covington, S. S. (2007). The Relational Theory of Women's Psychological Development: Implications for the Criminal Justice System. In R. Zaplin (Ed.), Female Offenders: Critical Perspectives and Effective Interventions (pp. 135-164). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

- Orr, C. et al. (2009). America's Problem-Solving Courts: The Criminal Costs of Treatment and the Case for Reform. National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

- Rousseau, D., PhD, LMHC, & Elizabeth Jackson, MPH. TIMBo Implementation in a Women's Correctional Facility – MCI Framingham Pilot.

- Walls, S. The Need for Special Veteran Courts.

Vicarious Trauma in the Legal System

The criminal justice system can cause or exacerbate trauma for all actors involved in each channel of the system. Criminal justice professionals as well as inmates experience trauma through law enforcement, courts and law, and corrections.

It is common to understand the trauma that can come from both law enforcement and correctional professionals due to high stress and the potential for violent scenarios. However, it is notable to realize that professionals within courts and law can experience trauma as well. A United Nationals article explains the vicarious trauma that judicial system professionals face (Vicarious Trauma, n.d.) Vicarious trauma is “the cumulative inner transformative effect of bearing witness to abuse, violence and trauma in the lives of people we care about, are open to and are committed to helping” (Vicarious Trauma, n.d.). Judges listen to evidence and make decisions with significant implications that affect members of society. This vicarious trauma can cause a negative world view, perceived threats to personal safety, loss of spirituality, or changes in self-identity, fear, empathetic distress, burnout, loss of relationships, mental or physical health issues, depression, or even coping with stress through food of substances” (Vicarious Trauma, n.d.). This proves that the trauma that judicial actors vicariously obtain can affect both their personal and professional lives.

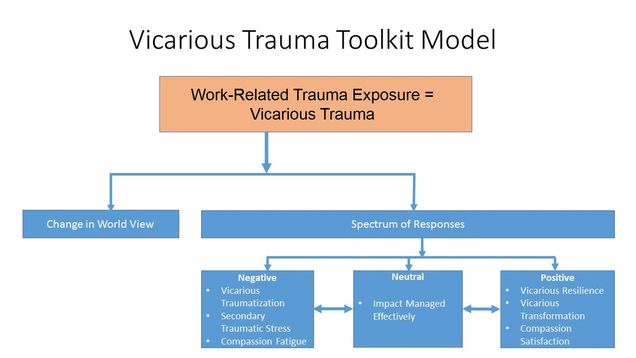

There are three different types of reactions to trauma exposure including negative, neutral, and positive reactions. Negative reactions include vicarious traumatization leading to secondary traumatic stress, compassion fatigue, and critical incident stress (Department of Justice, n.d.). Neutral reaction signifies a person’s resilience, experiences, support, and coping strategies that manage the traumatic material. Positive reactions lead to vicarious resilience and involves drawing inspiration from victim’s resilience to strengthen their own mental an emotional fortitude.

Luckily there has been efforts to address the trauma that judicial professionals have identified. First, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) include wellness aspects in their training conferences to build resilience for judges. They explain ideas of breathing techniques, nutrition, physical exercise, mindfulness practices, self-compassion, and advice from experts to develop tools to reduce stress and mitigate vicarious trauma (Vicarious Trauma, n.d.). Educating professionals early on how to deal with vicarious trauma offers these individuals the best opportunity to have positive outcomes when they face these situations.

Additionally, there are suggestions for coworkers, supervisors, and family members who might identify someone dealing with vicarious trauma. This involves reaching out and talking to them, supporting them, connecting them to resources, referring them to organizational support, allowing flexible work schedules, creating a positive physical space at work, maintaining routine, and more (Department of Justice, n.d.).

While the risks of vicarious trauma is detrimental to both physical and mental health in personal and professional lives, there are solutions. It is essential to educate professionals within the legal system about vicarious trauma, so they have both the knowledge and resources to combat it.

References

Department of Justice. (n.d.). What is vicarious trauma?: The Vicarious Trauma Toolkit: OVC. Office for Victims of Crime. https://ovc.ojp.gov/program/vtt/what-is-vicarious-trauma

Vicarious trauma experienced by judges and the importance of healing. (n.d.). https://www.unodc.org/dohadeclaration/en/news/2021/26/vicarious-trauma-experienced-by-judges-and-the-importance-of-healing.html

Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences and Their Impact on Native American Youth

Introduction

Native American communities have long grappled with a complex web of historical trauma, marginalization, and systemic challenges that have contributed to a disproportionate exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). These experiences—ranging from abuse, neglect, and exposure to domestic violence to the chronic stress of living in communities burdened by poverty and discrimination—are deeply interwoven with the legacy of colonization and forced assimilation. Research by Felitti et al. (1998) highlights that ACEs can have lifelong repercussions, while Evans-Campbell (2008) provides a contextual framework for understanding how historical trauma magnifies these effects in Native communities. As Rousseau (2025) notes, “From being exposed to violence, having educational disabilities, and enduring a life of trauma, most, if not all, juvenile offenders need mental-health services to prevent a further deep-end track into adult crime and adult mental illness”.

The Connection Between ACEs and Incarceration

The link between ACEs and later criminal behavior is well documented. Children who experience chronic trauma may develop maladaptive coping mechanisms that manifest as aggression or risky behavior. When compounded with limited access to quality education and economic opportunities, these factors create vulnerabilities that can lead to arrest and incarceration—a dynamic further explored by Chandler et al. (2011). This cycle of disadvantage is not merely a series of isolated incidents but a predictable outcome of systemic neglect and cultural disruption. Rousseau (2025) further explains that “the risk of suicide among juveniles who have entered the juvenile justice system is at an acute level. In fact, suicide is the leading cause of death among youths in detention facilities”.

Mental Health in Native American Communities

Mental health challenges are another critical concern emerging from this cumulative trauma. The forced removal of Native children from their families and communities through policies like boarding schools severed essential cultural ties that once provided resilience and a sense of identity. Such cultural disruption, combined with ongoing socio-economic stressors, has resulted in high rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other mental health conditions among Native American populations—a reality that further complicates the community’s recovery efforts (Evans-Campbell, 2008). Rousseau (2025) reinforces this by stating, “65% to 70% of youth in contact with the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental-health disorder. More than 60% of youth with mental-health disorders also have substance-use disorders”.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

The issue of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) further underscores the intergenerational impact of these adverse experiences. FAS, which results from prenatal alcohol exposure, leads to lifelong physical, behavioral, and cognitive disabilities. Research by May et al. (2009) indicates that the prevalence of FAS in Native American communities is not simply a matter of individual behavior; rather, it is deeply connected to the broader social determinants of health and the stresses that fuel substance misuse during pregnancy. Rousseau (2025) adds, “Alcohol is widely known to have harmful effects on a developing fetus. In fact, alcohol can cause damage in a variety of ways: It can alter the way that nerve cells develop and divide to produce new cells; it can directly kill nerve cells or derange the formation of axons, the projections that send brain messages from one cell to another”. This intergenerational transmission of disadvantage further hinders academic and economic opportunities, thereby reinforcing cycles of poverty and, indirectly, criminal behavior.

Suicide Among Native American Youth

Perhaps the most heartbreaking consequence of this complex interplay of factors is the alarmingly high rate of suicide among Native American youth. The loss of cultural identity, isolation, and the cumulative weight of personal and communal trauma can leave young people feeling hopeless. When these factors converge with barriers to accessing culturally relevant mental health care, suicide can tragically appear as the only escape. Stanley, Hom, and Joiner (2016) document how this interplay of cultural loss, isolation, and unresolved trauma significantly elevates suicide risk among Native youth. Rousseau (2025) states, “Nearly all individuals who attempt suicide exhibit warning signs. These signs can occur in the days or weeks prior to an incident. All individuals working within the criminal justice system should be aware of the signs and symptoms of suicidal behavior”.

Community and Culturally Informed Care

Despite these daunting challenges, there is hope in the commitment to healing through community and culturally informed care. Recognizing the profound impact of ACEs and addressing the root causes of these issues requires an investment in trauma-informed practices, culturally tailored interventions, and robust community empowerment initiatives. Integrating traditional healing practices with modern therapeutic approaches can begin to mend the deep emotional wounds inflicted over generations. Early intervention—particularly in prenatal and early childhood programs—can help mitigate conditions like fetal alcohol syndrome while comprehensive support networks offer the necessary resources to break cycles of poverty, crime, and despair.

Conclusion

Ultimately, addressing the multifaceted challenges faced by Native American youth is not only a matter of policy but also a moral imperative. By acknowledging the historical and ongoing struggles of these communities and committing to solutions that honor their cultural heritage and resilience, there is a path toward a future where every child has the opportunity to thrive. The journey toward healing is long and complex, but with targeted efforts and a deep commitment to justice and equity, the cycle of adversity can be broken, paving the way for a brighter, more hopeful tomorrow.

References

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

Evans-Campbell, T. (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(3), 316-338.

Chandler, M. J., Lalonde, C. E., & Whaley, C. M. (2011). The impact of historical trauma on intergenerational social processes and contemporary behavioral outcomes among Native American families. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 9(1), 23-42.

May, P. A., Gossage, J. P., Marais, A. S., Jones, K. L., Kalberg, W. O., Barnard, R. J., & Hoyme, H. E. (2009). Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement, 16, 152-160.

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 1: Thinking Like a Forensic Psychologist. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 2: Substance Use. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Rousseau, D. (2025). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. Boston University Metropolitan College.

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2016). Race, sex, and cultural factors influence the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and suicide risk among Native American adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research, 20(4), 514-523

Implementation of Trauma-Informed Services into Real-Life Situations

In 2018, a violent man walked into a hot yoga studio in Tallahassee, Florida; he opened fire, ultimately killing a Florida State University faculty member, Dr. Nancy Van Vessem, and my sorority sister, Maura Binkley (Holcombe et al., 2019). This incident not only shocked the tight-knit community of Florida State and those who knew the victims but also inspired policy changes for hate crimes throughout the state of Florida.

The perpetrator of this heinous crime, Scott Beierle, had many red flags pointing towards an attack such as this, all of which were ignored by law enforcement officials. Beierle had a history of sexual misconduct that started in childhood, as well as a documented hatred of women that spanned throughout his life; he had also received multiple reports of sexual misconduct during the time he served in the military, and he had been fired from substitute teaching jobs throughout Florida for inappropriately touching female students (Holcombe et al., 2019). Law enforcement officials who searched Beierle’s personal items found disturbing journal entries regarding ideas of brutally torturing women, and although Beierle took his own life directly following his attack, the assumed motivation for this crime was his deep-rooted hatred of women.

Although I never knew Maura personally, those who loved her say that she was one of the brightest lights, and there is no doubt in my mind that she would’ve changed the world if she was given the chance to. She was an animal lover, a leader in our sorority, and was planning to move to Germany following her graduation from Florida State (Maura’s Voice, 2024). I got the opportunity to know some of her best friends, her family, and my own sorority sisters who live in her legacy every day, and everyone who had the privilege of knowing Maura was truly rich in life.

A year following the Tallahassee hot yoga shooting, Maura’s Voice Research Fund was launched by Jeff & Margaret Binkley, Maura’s parents. The organization funds research through Florida State’s College of Social Work to address issues of violence and prevent future hate crimes against women. I had the opportunity for two years to work for this amazing initiative to research incel-perpetrated mass violence against women, as well as red-flag laws within Florida. Although sometimes this research was discouraging to look into, the personal relationship I was able to form with those closest to Maura reaffirmed that organizations such as Maura’s Voice have the potential to change policies and prevention efforts, as well as heal trauma over time.

In the aftermath of the attack, trauma is something that many people directly affected by this situation still struggle with. Jeff Binkley is someone that I was fortunate enough to talk to often, and although the pain of losing his only daughter will never leave him, the efforts he puts into maintaining her legacy are so admirable; even through his grief, he still came to our sorority house to talk to all of us, celebrate Maura’s birthday with us every year, and release balloons in memory of Maura. My sorority sisters who personally knew Maura, took so much time to let us get to know her through their eyes, and it truly felt as though she was still with us. Although this was an incident that had the ability to divide our community, it actually brought us all together to work for a common goal: to make sure Maura and Dr. Van Vessem’s stories are never forgotten.

Throughout this course, we have touched on trauma-informed services a few times. In Module 4, it is stated that for individuals to benefit from these services, trauma and coping mechanisms must be taken into account, and the four most important qualities in programs such as this are safety, predictability, structure, and repetition (Rousseau, 2025). Although no formal trauma services were used, I feel as though my sorority was able to implement these qualities to ensure that those who knew Maura were able to cope with their trauma following the shooting. In our sorority house, we had a room dedicated to Maura; it contained all of the decorations from her bedroom, and her parents designed it to reflect Maura’s personality. By far, this room was everyone’s favorite in the house and where we all felt most comfortable to speak about our feelings. It almost felt as if Maura was looking over us in this room, and it gave all of us, as well as Maura’s family and best friends, a place to visit and talk to her. Each year, on Maura’s birthday, we would all participate in a yoga class and then eat her favorite German dishes with her family. And each year, on November 2nd, the day Maura passed, we would talk about the research we were doing to aid in the prevention of attacks like this, and then we would release balloons to honor Maura and Dr. Van Vessem. These actions allowed our community to heal collectively following the shooting and provided those who knew Maura with the support to continue fighting in her legacy for policy changes.

References

Holcombe, M., Chavez, N., & Baldacci, M. (2019, February 13). Florida yoga studio shooter planned attack for months and had “lifetime of misogynistic attitudes,” police say. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/13/us/tallahassee-yoga-studio-shooting/index.html

Maura’s Voice. (2024, June 13). https://maurasvoice.org/#maurasstory

Rousseau, D. (2025, January). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. Reading.