CJ 725 Forensic Behavior Analysis Blog

Solitary Confinement: A Sentence Within a Sentence

The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture has denounced the use of solitary confinement beyond fifteen days as a form of cruel and degrading treatment that rises to the level of torture, yet it is not uncommon for individuals to endure long-term isolation with no relief (Casella et al., 2018, p. 1). In 2016, William Blake entered into his twenty-ninth year of solitary confinement at the Special Housing Unit (SHU) at New York’s Great Meadow Correctional Facility (Casella et al., 2018, p. 26). Narrowly escaping the death penalty, despite the sentencing judge wanting to “pump six bucks’ worth of electricity into [Blake’s] body,” Blake reflected, “When the prison gate slammed behind me, on that very day I would begin suffering a punishment I am convinced beyond all doubt is far worse than any death sentence could possibly have been […] I cannot fathom how dying any death could be harder or more terrible than living through all that I have been forced to endure for the past quarter century” (Casella et al., 2018, p. 26-27). Similarly, Jesse Wilson, serving a life sentence at ADX Florence, described his experience in the government’s only remaining supermax as a “clean version of hell” (Casella et al., 2018, p. 81). Imploring that his humanity remain intact, Wilson wrote of himself: “Past these tattoos and this penitentiary pain, I remain, a son, a brother, a friend, and a human being. It sometimes feels that is forgotten” (Casella et al., 2018, p. 81). In addressing the inhumanity of solitary confinement, Wilson continued:

I refuse to embrace the solitude. This is not normal. I’m not a monster and do not deserve to live in a concrete box. I am a man who has made mistakes, true. But I do not deserve to spend the rest of my life locked in a cage– what purpose does that serve? Why even waste the money to feed me? If I’m a monster who must live alone in a cage, why not just kill me (Casella et al., 2018, p. 82)?

The adverse effects of solitary confinement appear to be related primarily to the length and conditions of imprisonment. Although it has not been conclusively established that short periods of isolation produce negative outcomes for the emotional well-being of inmates, long-term solitary confinement does, especially in relation to the psychological adjustment of prisoners (Arrigo & Bullock, 2008, p. 627). Serving as an expert witness for the plaintiff convicts in a class-action suit challenging the conditions of confinement in the SHU at Pelican Bay State Prison in California (Madrid v. Gomez, 1995), psychologist Craig Haney (2006) noted that the rigid conditions of solitary confinement and the absence of socialization encourages inmates to become “highly malleable, unnaturally sensitive, and vulnerable to the influence of those who control the environment around them” (p. 5). Ironically, long-term social isolation often leads to social withdrawal– individuals move from craving social contact to fearing it (628). Furthermore, prisoners housed under conditions of confinement grow to rely on the prison structure to limit and control their behavior. Consequentially, convicts are no longer able to manage their conduct when returned to the general prison population or when released back into the community (628).

It has been well documented that prisoners in long-term solitary confinement are at increased risk for developing symptoms of mental illness (Grassian, 1983; Haney, 2006). Specifically, social isolation is correlated with clinical depression and long-term impulse-control disorders (Arrigo & Bullock, 2008, p. 628). It has been amply demonstrated that the conditions of solitary confinement can produce symptoms of mental illness even in healthy prisoners. Convicts with preexisting mental illness are, however, especially susceptible to suffering damaging consequences from long periods of isolation, such as the development of psychiatric symptoms (632). In 1997, the Human Rights Watch estimated that five percent of the general prison population experienced some form of psychiatric illness, whereas more than half of the prisoners in segregation units suffered from psychiatric illnesses (Human Rights Watch, 1997). Psychosis, suicidal behavior, and self-mutilation are commonly seen among prisoners in long-term solitary confinement (Haney, 2006; 628). Considering this, it must be noted that suicide continues to be a leading cause of death in correctional facilities across the United States (Hayes, 2011, p. 1). In 2006, the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives (NCIA) entered into a cooperative agreement with the United States’ Justice Department’s National Institute of Corrections to conduct a national study on penitentiary suicides that would determine the extent of inmate suicides (Hayes, 2011, p. 1). The data indicated that the suicide rate in detention facilities during 2006 was thirty-eight deaths per one-hundred-thousand inmates, a rate approximately three times greater than that of the general population (Hayes, 2011, p. 3). One 2004 Austrian case control study, in an attempt to identify characteristics that distinguish prisoners who commit suicide from other prisoners, found five specific factors: (1) a history of attempted suicide or suicidal communications; (2) psychiatric diagnosis; (3) psychotropic medication prescribed during imprisonment; (4) a highly violent index offense; and (5) single-cell accommodation (Fruehwald et al., 2004) (note: it is unclear if these same factors are cross-culturally transferable).

With the complete isolation and austere conditions of solitary confinement having been shown to induce psychiatric symptoms in its recipients, solitary has proven to be a sentence within a sentence. “People,” begins Jean Casella, co-author of Hell Is a Very Small Place: Voices from Solitary Confinement, “are supposed to be sent to prison as punishment, not for punishment” (Casella et al., 2018, p. 10). According to the law, deprivation of freedom alone is supposed to be the price society demands for crimes committed. Additional suffering endured within prison at the hands of officers and administrators can then be seen as extrajudicial, and cruel and unusual. Former president Barack Obama, on the topic of long-term solitary confinement, said, “Do we really think it makes sense to lock so many people alone in tiny cells for twenty-three hours a day for months, sometimes for years at a time? That is not going to make us safer. It’s not going to make us stronger” (Obama, 2016). Therefore, solitary confinement as a punishment must be re-thought.

Works Cited

Arrigo, B., & Bullock, J. (2008). The Psychological Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prisoners in Supermax Units. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 52 (6).

Casella, J., Ridgeway, J., & Shourd, S. (2018). Hell is a very small place: Voices from solitary confinement. New York: New Press.

Fruehwald S, Matschnig T, Koenig F, Bauer P, Frottier P. (2004) Suicide in custody: a case-control study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 185: 494-498.

Grassian, S. (1983). Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140(11), 1450-1454.

Haney, C. (2006). Reforming punishment: Psychological limitations to the pains of

imprisonment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hayes, L. 2011. National Study of Jail Suicide: 20 Years Later. National Jail Exchange.

Human Rights Watch. (2000). Out of sight: Super-maximum security confinement in the United States.

Madrid v. Gomez. (1995).

Obama, B. (2016). Why we must rethink solitary confinement. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/barack-obama-why-we-must-rethink-solitary-confinement/2016/01/25/29a361f2-c384-11e5-8965-0607e0e265ce_story.html?utm_term=.49f6ef5c16b6

The Faces of Trauma: Migrant Children

The Faces of Trauma: Migrant Children

Getty Images, 2018

Getty Images, 2018

Look at the face of this little boy. Does he look like a criminal or someone who wants to come to our country to stir up trouble? Look at his mother’s face the look of desperation as she must feel helpless not just for her plight but for her inability to calm her child down. The most recent caravan loaded with refugees coming from Central America are leaving their country plagued by violence and poverty. It is estimated that the caravan is loaded with approximately 9,300 refugees and 2,300 are children traveling towards the USA seeking asylum (Schlein, 2018). Our US present Donald Trump has referred to these groups of people as “Stone Cold Criminals” and has gone as far as deploying 15,000 troops to San Ysidro to secure the border which is the exit and entry from the Tijuana borderline. Our president has instructed the US troops to use all force necessary and even made threats to close the border permanently if necessary. The caravan immigrants have settled in the city of Tijuana, Mexico near the border. Only 100 applicants per day are being processed and with the long waits in line on top of the migrants that are expected to arrive, this lead to an act of desperation and violence between the US agents and the refuges that have made attempts to cross the border illegally last month. US agents fired tear gas at both adults and children and many were arrested trying to cross the border illegally. It may take months or even years for cases to get processed and heard. Some of the migrants are heading back home while others along with their children are still camping out in the city of Tijuana, Mexico clinging on to hope (Gomez & Jansen, 2018).

Schlein, 2018

Schlein, 2018

As the wait for asylum petitions continue, other children and families travel on cattle trucks (see above picture), cargo trains, or get a lift from kind people as they slowly make their way through Mexico towards the US border. This is a dangerous journey these families are making as they risk getting assaulted, robbed, raped, or even killed. Meanwhile what happens to these children as they embark on this journey initiated by their parents and caretakers? What goes on in their minds as they are faced with an unwelcoming government via excessive force? They are fleeing their homeland plagued by violence and poverty only to meet with an uncertain future and the possibility that they may have to return back home if their petitions for asylum are denied, that is if their petition is ever heard. Lynn Smithwick facilitator for METCJ 725 covered some valuable information on types of trauma during Module 5 live lecture. In this live lecture it was mentioned that children are “fragile” and witnessing any type of trauma can have an adverse effect in a child’s life. Smithwick addressed four types of vicarious trauma:

- Acute Trauma: a single even that is limited in time such as death or a shooting.

- Chronic Trauma: the experience of traumatic events over a long period of time such as poverty in inner city youth and witnessing violence.

- Complex Trauma: both exposure to chronic trauma as well as multiple and various forms of trauma.

- System Induced Trauma: the traumatic removal from home, admission to a detention center or residential facility, or multiple placements within a short period of time. For example when child protection services gets involve and removes the child, being placed in foster care, or being detained at a juvenile hall.

Smithwick stated that exposure to trauma can occur from events such as being in a car or other serious accident; having a significant health concern or hospitalization; sudden job loss; losing a loved one; being in a fire, hurricane, flood, earthquake, or other natural disaster; and experiencing emotional, physical, or sexual abuse (Smithwick, 2018: Module 5). What types of trauma do you think these children have been exposed to? All four! They are leaving their loved ones behind in their quest for a better future, their life has been a constant exposure to violence, their exposure has been a chronic one, and the system from where they come from and where they are going are not making things any better for them as they move from camp to camp waiting for their turn to have their case heard.

Hasan, 2018

Hasan, 2018

Here a family surrenders to US Border Patrol after crossing the border wall into the US on December 2, 2018.

Syeda Javeria Hasan, a student from the University of Waterloo, wrote an analysis about the challenges a parent can face during this caravan journey. Hasan reports that the six week journey can hit children the “hardest” because of the physical requirements they are exposed to during this travel. This can impact parent and child relationship. Refugee parents and children often exhibit symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression. This can leave parents feeling emotional worn out which can lead to “over-protectiveness, harsh discipline, and a reversal of parent/child roles”. Hasan reports that as the caravan migrants traveled the 4,000 kilometers from Honduras to Tijuana, Mexico, they are more prone to fevers, eye infections, lice infestations, respiratory illness, and dehydration. As the city of Tijuana makes efforts to provide shelter to the thousands of migrants as they arrive, the shelters are not in the most hygienic conditions and this only increases the health concerns of children since they are more vulnerable to diseases. Over time the strain this add to parenting can lead to low nurturance and low responsive to needs of the child. Hasan reports that when exposed to constant community violence, parents starts to feel “hopeless, powerless, emotionally overwhelmed”, leading to symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Parents can also start to dissociate and have a decrease in understanding their child’s own psychological distress. This can result in a child developing emotional challengers, learn to disengage, and develop similar coping mechanisms as their parents (Hasan, 2018). Leaving behind their culture just to get away from the violence only to face a new form of uncertainty in a foreign country these migrants will have to adapt as they seek shelter and make their way towards the US border in hopes of obtaining political asylum, is troubling enough and not to mention what the children are being exposed to. Is there hope for these people as they await their fate at the border?

Schlein, 2018

Schlein, 2018

A youth from Honduras rests in a public area in Tecun Uman, Mexico enroute to USA as he waits to re-join with more migrants.

This picture breaks my heart just like the rest. This young man can be my son. Look closely at his face; he seems to have psychologically tuned out in order to endure the hardship that awaits him but prefers to risk it all in hopes of making it past the US border. President Trump is trying to make them go away and return them back to their homelands. One federal judge stated that our president can’t do that. US district judge Jon Tigar has suspended the administration’s new policy to cut off asylum to immigrants who enter this county by illegal means. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, states that “any foreigner who arrives in the USA, whether or not at a designated port of arrival, may apply for asylum” (Gomez & Jansen, 2018). President Trump cannot overturn a law that was specifically made to give asylum from those who seek it. I understand that criminals may be on their way with the caravan but not everyone is a criminal. Instead of deploying thousands of troops to protect the US border why not increase the staff at the port of entry in order to thoroughly and swiftly process petition applications in order to alleviate some of the strain and chaos this whole event has caused. That way immigrants can decide based on their petition response, whether to make Mexico their new homeland, seek asylum at another county, or reunite with their loved here in the USA if entry access is approved. Anything is better than keeping them camping at the Mexican border, especially for the already vulnerable groups: the children.

Gomez, A. and Jansen, B. (2018). President Trump call caravan immigrants ‘stone cold criminals.’ Here’s what we know. Retrieved December 10, 2018, from https://amp.usatoday.com/amp/2112846002

Hasan, S. J. (2018). The challenges of parenting in a migrant caravan. Retrieved December 10, 2018, from https://theconversation.com/amp/the-challenge-of-parenting-in-a-migrant-caravan-107875

Schlein, L. (2018). UN: Migrant Caravan Children Suffering Extreme Hardships. Retrieved December 10, 2018, from https://www.voanews.com/amp/un-migrant-caravan-children-suffering-extreme-hardships/4630708.html

Smithwick, L. (2018). Module 5 live lecture: Best Practices-Juvenile Justice and Gender

Responsivity. Accessed online November 28, 2018. https://learn.bu.edu

Picture of child with mother copied November 29, 2018, from www.gettyimages.com

Enrique S. “Kiki” Camarena… The beginning of “Red Ribbon Week”

Enrique “Kiki” S. Camarena was a United States, DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) Special Agent who was kidnapped, tortured, and killed in Mexico in 1985. The effects of this horrific tragedy shook the DEA, The United States, and Mexico. After Kiki went missing, while working in Mexico, the United States embarked on the most significant manhunt it had ever attempted until this time. The United States, especially the DEA, began hunting the person or people that had taken part in Special Agent Camarena’s kidnapping, torture, and murder.

Kiki was a decorated and valued DEA Special agent, but his story begins before he ever was employed by the DEA. In 1968 Kiki joined the United States Marine Corps. After serving in the Marine Corps for about two years, he joined the Calexico Police Department as a Criminal Investigator in 1970. In 1973, Kiki started working as a Narcotics Investigator with the El Centro Police Department (DEA.Gov). Kiki would stay with the El Centro police department until 1974. In June of 1974, Kiki joined the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Initially, Kiki would be assigned to some familiar territory in Calexico, California as a Special Agent with the DEA. Kiki had many resources with the local people as well as the local police department in Calexico, because of his prior service in the city. In 1977 he was assigned to the Fresno district office in northern California. Kiki had an unmatched work ethic and an overwhelming never quit attitude; this allowed him to make some great connections with the local people and with the state officials while working in the district office. His Strong work ethic, his never quit attitude, along with being fluent in Spanish, made him a prime candidate to be assigned to Mexico in 1981, where he would work out of the Guadalajara Resident Office (DEA.Gov).

Kiki and his family moved to Guadalajara, Mexico in 1981. For four and a half years, Kiki remained on the trail of Mexico’s most significant marijuana and cocaine traffickers. “In early 1985, he was extremely close to unlocking a multi-billion-dollar drug pipeline. However, before he was able to expose the drug trafficking operations to the public, he was kidnapped on February 7, 1985” (DEA.Gov).

According to redribboncoalition.com, "his efforts led to a tip that resulted in the discovery of a multi-million-dollar narcotics manufacturing operation in Chihuahua, Mexico. The successful eradication of this and other drug production operations angered leaders of several drug cartels who sought revenge.” Camarena was kidnapped on February 7th, 1985 by five armed men, driving a Volkswagen car, in the middle of the day while on his way to have lunch with his wife. Camarena's Mexican pilot, Alfredo Zavala-Avelars, was also kidnapped in a separate but related incident, according to redribbonweek.com (Flores)

“At almost the same hour, Alfredo Zavala Avelars, a professional pilot for the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture, was seized by cartel operatives as he drove into the city from Guadalajara's international airport, where he had just landed. Zavala was a close friend of Camarena and a DEA mole, regularly providing information about the comings and goings of regional drug lords who traveled in and out of the city aboard private aircraft, which he monitored and reported. Zavala, too, was forcibly carried to the house, for ‘interrogation.’” (The death house on Lope de Vega)

Kiki was kidnaped right in front of the Mexican Consulate’s office in Guadalajara. Five armed men grabbed him and threw him in a car. It is reported that they took him to a ranch that is known for drug activity and they kept him there for approximately three days. It was later discovered that Kiki was surrounded by Mexican intelligence officers from the DFS (a Mexican intelligence agency that no longer exists) while being kidnaped and tortured.

Kiki was held at 881 Lope de Vega in Guadalajara; this house was owned by Rafael Caro Quintero. Kiki was held against his will at this location for about three days. During this time Kiki was subjected to numerous torture techniques for over 30 hours. Quintero and others brutally assaulted Kiki over and over again. They crushed his skull, jaw, nose, and cheekbones by beating him with a combination of fists and a tire iron. They broke his ribs with numerous assaults to his mid-section. They were so brutal in their attack that they even drilled a hole in his head, and if that was not enough, they also tortured him with a cattle prod.

The torture that Kiki Camarena underwent was so intense that he passed out from the pain and almost died a few times during these torture sessions. Quintero was such a psychopath about the tortures that he ordered a cartel doctor to keep Kiki alive. "At that point, he administered lidocaine into his heart to keep him alert and awake during the torture," (Jeunesse). Due to his numerous wounds from the torture, eventually Kiki could no longer be kept alive, and he died on February 9th, 1985.

Kiki was kidnapped and murdered because he was smart enough to realize that in order to capture the cartel leaders, the DEA would need to chase the money and not the drugs. "We were seizing a huge amount of drugs. However, we were not disrupting the cartels. So he came up with the idea that we should set up a task force and target their monies." (Jeunesse)

Nobody in Mexico anticipated the reaction that the United States would have to this horrendous act. The Mexican Government seemed as though they were not doing what needed to be down in order to catch the people responsible for Kiki’s death. The United States kept the pressure on the Mexican Government to bring the responsible parties to justice. However, the Mexican government would consistently ignore requests from the United States. Frustration with the Mexican Government was growing stronger by the day. In an interview with FRONTLINE in 2000, Jack Lawn, the former Administrator of the DEA at the time of Kiki’s death, stated;

“The Mexican government knew what happened, and it became more clear to us that the government of Mexico indeed was covering up the assassination, the killing of Kiki Camarena. When we talked [to them about finding the body], they said, "Well, we have Mexican officers killed all the time. You may never get the body back." Moreover, our response was, "Just look how we feel about the MIAs." At that time, we had some 3000 MIAs missing from Vietnam. It continues to be a major issue.” (Drug Wars)

In February of 1985, the Customs Service Commissioner, William Von Raab, who was responding to an appeal from Francis M. Mullen Jr., the head of the Drug Enforcement Administration, ordered all U.S. Customs agents at every one of the 15 official crossings into and out of Mexico, to carry out an excruciating task of thoroughly inspecting every vehicle, looking for Kiki’s body. This operation came to be known as Operation Camarena.

“No one seriously believed that Camarena, an eleven-year DEA veteran, would turn up in the search. Instead, the border operation was the Reagan Administration's way of trying to force the Mexican government of President Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado to step up its hunt for the missing agent.”

“All along the 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexican border, everything on wheels was stopped and thoroughly inspected and searched. At the point known as the "world's busiest border crossing," between Tijuana and San Ysidro, Calif., the usual 20-minute delays on the 22-lane northbound approach plaza dragged on for as long as seven hours.” ("DD")

Many people criticized William Von Raab for his decision to “close the border.” However, within a week of the border being closed, Kiki’s body was recovered due to an “anonymous” letter that was sent to the police in Mexico with information about the location of Kiki’s body.

In March of 1985, the bodies of Enrique “Kiki” S. Camarena and Alfredo Zavala Avelars were found in Michoacán state which is located just southwest of Jalisco. The bodies were first buried in a wooded site in a metro area, and then later dug up and planted in the site that they were to be found at. Both of their bodies were badly decomposed when they were found by a farmer who was working his fields.

The United States authorities placed enormous pressure on the Mexican government to locate the people behind Kiki’s death. Due to this pressure, the Mexican government would eventually arrest, prosecuted and convicted Rafael Caro Quintero and others from the Guadalajara Cartel operations. Quintero was sentenced to 40 years in a Mexican prison. However, after serving only 28 of those years, a federal tribunal in Guadalajara ordered the drug lord's immediate release. The court's order was faxed to his place of incarceration and Quintero exited the Jalisco state prison 90 minutes later on August 9th, 2013.

“According to prison guards, Caro Quintero left with nothing but a small bundle of clothing, walking a kilometer up a dark and rain-slick road to the nearest highway, where unidentified persons waited for him in a car.” (The death house on Lope de Vega)

“Shortly after Kiki's death, Congressman Duncan Hunter and high school friend Henry Lozano launched Camarena Clubs in Kiki's hometown of Calexico, California. Hundreds of club members including Calexico High School teacher David Dhillon wore red ribbons and pledged to lead drug-free lives to honor the sacrifices made by Kiki Camarena and others on behalf of all Americans.”(DEA)

“Red Ribbon Week eventually gained momentum throughout California and later across the United States. In 1985, club members presented the "Camarena Club Proclamation" to then First Lady Nancy Reagan, bringing it national attention. Later that summer, parent groups in California, Illinois, and Virginia began promoting the wearing of red ribbons nationwide during late October. The campaign was then formalized in 1988 by the National Family Partnership, with President and Mrs. Reagan serving as honorary chairpersons. Today, the eight-day celebration is an annual catalyst to show intolerance for drugs in our schools, workplaces, and communities. Each year, on October 23-31, more than 80 million young people and adults show their commitment to a healthy, drug-free lifestyle by wearing or displaying the red ribbon.”(DEA)

Works Cited:

"DD." How Kiki Camarena's Murder Nearly Brought Down the Mexican Government and Economy. 10 August 2013. / 15 April 2015.

<http://www.borderlandbeat.com/2013/08/how-murder-of-kiki-camarena-nearly.html>.

DEA.Gov. Kiki and the History of Red Ribbon Week. 02 April 2015. / 14 April 2015.

<http://www.dea.gov/redribbon/RedRibbon_history.shtml>.

Drug Wars. Frontline. 10 October 2000. / 14 April 2015. <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/etc/transcript2.html>.

Flores, Roman. A look into slain DEA agent Enrique Camarena's story during Red Ribbon Week. 27 October 2011. / 13 April 2015.

<http://articles.ivpressonline.com/2011-10-27/dea-agent_30330461>.

Jeunesse, William La. US intelligence assets in Mexico reportedly tied to murdered DEA agent. 13 October 2013. / 13 April 2015.

<http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2013/10/10/us-intelligence-assets-reportedly-played-role-in-capture-dea-agent-in-mexico/>.

The death house on Lope de Vega. MGR-The Mexico Gulf Reporter 17 August 2013. / 14 April 2015.

<http://www.mexicogulfreporter.com/2013/08/the-death-house-on-lope-de-vega.html>.

Do All Juvenile Prevention Programs Work?

Juvenile delinquency is a passionate subject for me for many reasons. I can go on for days and hours just discussing this topic because of my experience as a minority brought up in an urban community. It is unfortunate to say that the majority of my friends growing up did not make it to see 18 years of life or even make it to live a crime-free life. As a teenager, I always tried to insert some knowledge to all my friends to do the right things to prevent jail time or even death but unfortunately, my advice did not work. At the time I thought my advice did not work because either at home their parents were not setting a good example or there weren’t enough programs available to help deter juveniles from participating in crimes in the future.

I came across a great article on governing.com called Programs Like D.A.R.E. and Scared Straight Don't Work. Why Do States Keep Funding Them? This article made me realized that urban communities do in fact have programs to help deter future criminals but the programs are just simply broken.

Let me brief you guys about the Scared Straight program

Scared Straight is a program intended to deter juveniles from participating in future crimes. Juvenile and at-risk youth visits prisons and observes first-hand prison life and interacts with adults prisoners. The goal of this program is to demonstrate to these juveniles what is like to be incarcerated in the hope to “scare them straight” and deter them from future crimes.

The Scared Straight intervention was found to be more harmful than doing any good. Studies have found that Scared Straight programs are purely not effective in deterring criminal activity, in fact, the intervention “may be harmful and increase delinquency relative to no intervention at all with the same youths” (Hale, 2010). The Scared Straight programs are not deterring youth from future violation of the law, but it is oddly increasing the chances of the juvenile ending up behind bars.

The million dollar question is why still fund programs that have been found to be more harmful than doing any good?

The main reason why programs like Scared Straight continue to be funded and supported by the government is that strong constituencies back the interventions. The federal Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking has been advocating to bring more analysis policy decision. They have pointed to use randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which help test whether or not the program works. The issues have been that RCTs are very expensive and state and local government cannot afford them, there for the local government officials get “sucked into programs backed by strong constituencies but that offer no evidence of effectiveness” (Kettl, 2018). Due to the loyal advocate of programs, the government ends up spending a lot of money into programs that do not work. Overall, many state governments have been stubbornly stuck with the program until the Justice Department has warned them that they could lose funding if they continue to use the program.

Better programs needs to be put in place to help break the cycle.

References

Hale, J. (2010, November 27). Scared Straight? Not Really. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/blog/scared-straight-not-really/

Kettl, D. (2018, June). Programs Like D.A.R.E. and Scared Straight Don't Work. Why Do States Keep Funding Them? Retrieved from http://www.governing.com/columns/washington-watch/gov-dare-drug-programs.html

Suicide in Prisons

A topic I found very interesting in this course was Suicide (Lesson 4.3). In this lesson, we learn how suicide is ‘an issue of great importance’ and that it is the ‘leading cause of death in jails and prisons’ (Rousseau, 2018). My goal for this blog is to provide a further explanation on this topic and to see what else has been discovered on this topic. First off, we know that suicide is a serious health problem. It has been seen that the ‘World Health Organization estimates that one suicide attempt occurs approximately every three seconds, and one completed suicide occurs approximately every minute’ (World Health Organization, 2007).

Seena Fazel further researched suicide in prisons and did an international study of suicides in prisons as well as the contributory factors. In her study, it was seen that ‘prison suicide is an international problem, and rates of suicide in prisoners are higher than in general populations’ (Fazel, 2017). Fazel also states that ‘a clearer understanding of factors explaining the elevated risks can assist in suicide prevention initiatives’ (Fazel, 2017). This is very important because prison suicides are clearly an issue and any ideas or suggestions that can help prevent them should be welcomed. Fazel therefore obtained data from 24 different countries and collected statistics in regards to prison suicides and deaths. She also tested a number of ecological prison variables that could have been suicide risk factors. These risk factors included incarceration rates, rates of overcrowding, ratios of prisoners to prison staff and prison population turnover ratios. Fazel’s overall findings state that ‘there are no simple ecological explanations for prison suicide. Rather, it is likely to be due to complex interactions between individual-level and ecological factors.

Thus, suicide prevention initiatives need to draw on multidisciplinary approaches that address all parts of the criminal justice system and address individual and system-level risk factors’ (Fazel, 2017). This is very interesting because it was determined that there are multiple factors working together as to why one would commit suicides in prison. Therefore, multiple steps must be taken in order to ensure that individuals are getting the help that they need in prison. It has been seen that suicide prevention is challenging because one needs to identify the individuals that are ‘most vulnerable, under which circumstances, and then effectively intervene’ (World Health Organization, 2007). The World Health Organization launched an initiative in hopes to provide reasoning for why inmates commit suicides and how this can be prevented. The World Health Organization states the same thing that Fazel states in that a combination of individual and environmental factors can explain the high rates of suicide in prisons. One of the first factors is that prisoners tend be at risk individuals who are vulnerable. They have mental disorders, or have substance abuse problems and are socially disenfranchised. Following this factor, the psychological impact of getting arrested and being incarcerated affect these individuals by causing them more stress therefore making them more vulnerable. Another factor is that some places have no formal procedures or policies to identify individuals that are at risk. Even if there are places with formal procedures and policies, corrections staff may miss warning signs of suicide risk. One last factor is that there might not be any mental health programs in these correction facilities therefore these individuals have no access to help or treatments. These factors should all be taken into consideration when coming up with a plan or program to try and attempt to decrease the risk of suicides in inmates.

In terms of what can generally be done, first and foremost, it would be essential to have some sort of suicide prevention program set up. In this program, training would be very important. All correctional staff, health care and mental health care staff should be involved. Another factor of this program should be intake screening. Suicide screening should be done often for all inmates. Following this, post-intake observation should take place. Inmates should be observed for any warning signs. After this, management following screening should be conducted where follow up reports and observation notes are taken down. This includes monitoring inmates, watching their communication, social skills and how they are reacting to their environment should be looked at. Mental health treatment should be given to those that do pose a risk. If a suicide attempt or a suicide occurs, a debrief should take place and the program should be altered to account for why that event occurred in hopes that it never happens again. It has been seen that corrections facilities continue to try and improve the policies and procedures already set in place. With more research, corrections facilities can continue to improve on the systems that they already have set in place in order so that the risk of suicides for inmates decrease.

Fazel, S. (2017). Suicide in prisons: an international study of prevalence and contributory factors. The Lancet Psychiatry. Vol 4 (12).

Rousseau, D. (2018). Module 4. Retrieved from: https://onlinecampus.bu.edu

World Health Organization (2007). Preventing Suicide in Jails and Prisons. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int

Online Child Sexual Abuse: The Invisible Offenders

Child sexual abuse or sexual extortion of children is an overlooked and under-reported crime, perpetrated by respected and trustworthy members in communities across the world. With the internet constantly growing and becoming more accessible, child sexual abuse has moved to the world wide web. Online child sexual abuse can include sextortion, live streaming of sexual abuse, and the grooming of children for sex. “Online sexual offending refers to the use of internet and related digital technologies to obtain, distribute, or produce child pornography, or to contact potential child victims to create opportunities for sexual offending” (Bartol & Bartol, 2017, p.396).

The online sexual extortion of children and adolescents is a very significant threat currently. Children and adolescents use the internet everyday whether it’s on a smartphone, laptop or iPad. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children defines Sextortion as a form of sexual exploitation that “occurs primarily online and in which non-physical forms of coercion are utilized, such as blackmail, to acquire sexual content (photos/videos) of the child, obtain money from the child or engage in sex with child” (NCMEC, 2016). The internet allows individuals to change who they are. Online predators have the ability to make themselves a different appear to be a completely different person. They use messaging platforms, social media sites, and video chat applications. Grooming techniques are used to gain trust and build a relationship with potential victims. Time is spent learning about interests, complimenting, and showing a lot attention. Online sexual predator can offend without ever having physical contact with their victims and leave the scene of the crime without a trace.

The trauma experienced by victims of online sexual extortion is like those who experience child sexual abuse in the physical world. There are those same feelings of fear, shame, and guilt. Many online predators use extortion or “sextortion” to get what they want. They use the threat of posting the pictures or videos online or sending them to family members and friends. Victims of child pornography also experience significant trauma. There is a permanent record of the abuse they experienced, although the actual abuse is no longer occurring. It is not possible for law enforcement to recover every image of child pornography that has been distributed through the internet. Nor is it possible for every online sexual predator to be apprehended by law enforcement. In cases involving child pornography, it possible that a child may be unaware that any photos or videos exist. However, if they ever learn about them it can be equally traumatizing. The knowledge of photos or videos can bring back traumatic memories and cause further emotional damage. In some cases, the offender may show those images to others in the presence of their victim. Causing the victim to have feelings of shame and embarrassment, especially if they know or like the other individuals.

In order to prevent the online sexual exploitation of children, there needs to be education provide to parents and children. The internet is used for everything, from shopping to connecting with friends. The increasing popularity of live video streaming and online messaging increases the risk of online child sexual exploitation.

Bartol, C., & Bartol, A. (2017). Criminal Behavior: A Psychological Approach, 11th Edition. Boston: Pearson.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Sextortion. Retrieved December 10, 2018 from http://www.missingkids.com/theissues/onlineexploitation/sextortion

Cultural Competency and Trauma in Criminal Justice

Cultural competency is an important factor in dealings with any populations with racial, ethnic, or religious considerations. “Cultural and linguistic competencies is a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables effective work in cross-cultural situations.” (Rousseau, 2018). Though I cannot speak specifically regarding all cultures, I can speak about the unique cultural considerations of the Indigenous people in the United States and Canada.

Indigenous people in the U.S. and Canada have a long history of abuse and traumatic events but what many people do not realize is that this trauma has impacted all generations. Historical trauma is the “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding across generations, including the lifespan, which emanates from massive group trauma.” (delVecchio, 2015). The trauma is passed down from one generation to the next through storytelling, physical and emotional abuse, and addiction. Many people are aware of some of the more prominent instances of injustices to the indigenous people, including colonialism, the Trail of Tears, and Wounded Knee. However, history books often overlook one of the darkest and most impactful periods in Native history – the residential school era.

Residential schools came about as a way to assimilate indigenous communities to a more European lifestyle. One of the more famous schools was the Carlisle Indian School whose founder, Lt. Richard Pratt, came up with the motto “Kill the Indian to Save the Man” (Pember, 2017). Native children were taken away from their families, usually by force, and housed in the residential schools for most of the year. The long hair of the boys, an important symbol in Native culture, was cut short, the children were forbidden to speak their language, abused physically and sexually, forcefully sterilized, and malnourished. Many children died, their deaths often not being reported to their families until long after, and they were buried in unmarked graves. It is estimated that about 6,000 children died in the residential schools in Canada alone (Pember, 2017). The last of these schools did not close until the early 1990s and the effects of colonialism and assimilation are very present in indigenous communities today.

Today’s Native communities are suffering from domestic violence, mental health issues, high suicide rates, addiction, and poverty. Many people have lost their language, culture, and identity. Michelle Obama put the suffering of the indigenous communities into perfect context. She said “Folks in Indian Country didn’t just wake up one day with addiction problems. Poverty and violence didn’t just randomly happen to this community. These issues are the result of a long history of systematic discrimination and abuse. We began separating children from their families and sending them to boarding schools designed to strip them of all traces of their culture, language and history.” (Pember, 2017). In order to better support indigenous people throughout the criminal justice system, it is vitally important to understand where these problems come from and how to use the positive aspects of the culture, such as traditional medicine, sweat lodges, family support, and traditional teachings, to rehabilitate offenders.

Here is a link to a recent story about how my own community (Akwesasne) is rebuilding the foundations of language after the significant losses from the residential school era (please forgive the reporter’s mispronunciation of Akwesasne):

As Native American history month comes to a close, a rare and intimate look at New York’s Mohawk tribe and their fight to restore their culture.For more information and to support the Akwesasne Freedom School visit the Friends of the Akwesasne Freedom School (https://www.foafs.org).

Posted by MetroFocus on Friday, November 30, 2018

References:

Rousseau, D. (2018). Module 4: Implementing Psychology in the Criminal Justice System. Retrieved from https://onlinecampus.bu.edu/webapps/blackboard/execute/displayLearningUnit?course_id=_50742_ 1&content_id=_6167937_1&framesetWrapped=true

delVecchio, P. (2015). The Impact of Historical and Intergenerational Trauma on American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. Retrieved from: https://blog.samhsa.gov/2015/11/25/the-impact-of-historical- and-intergenerational-trauma-on-american-indian-and-alaska-native-communities

Pember,M.A. (2017). When Will U.S. Apologize for Genocide of Indian Boarding Schools? Retrieved from: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/mary-annette-pember/when-will-us-apologize-fo_b_7641656.html

PTSD… A “Hood Disease”

When folks think of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the first thing that usually comes to mind is veterans. However – there is a very close parallel to the atmosphere of war to the atmosphere of living in the inner city. The things that some individuals who live in urban areas, are exposed to can often be traumatic. From poverty to gang-violence, people in inner cities witness events that do not typically transpire in suburbs. These experiences lead to this notion of a “hood disease” (Cole 2017).

Many studies have been conducted that come to the conclusion that the connection between inner city youth and PTSD can lead to violence. Not only is this a criminal justice issue but a public health one as well. What is being done to address it?

I have seen how PTSD affects both populations – veterans (my father) and inner city youth (my clients). There are many commonalities in their behavior and how it manifests in them. What is also interesting to me is that my father was an inner city kid. Did being in the Vietnam War exacerbate his PTSD? Constantly looking over your shoulder and not being able to sit with your back towards the door are two things that my father and my clients have in common.

Inner city violence “has insidious effects on the psychological health of urban civilians”, whether you are a direct victim or are merely exposed to it (Gilkin et. al. 2016). Imagine walking down the street and on every corner there are lit candles, teddy bears, and empty liquor bottles in memory of a homicide victim. The scene is morbid. The aura is often the same. Constantly hearing that your friends or your neighbors were shot at or killed. Innocent peoples lives being taken in a mistaken identity.

Fight or flight. The smartest decision would be flight. But if your family is already experiencing poverty, packing up and leaving is not even an option. So again I ask, what is being done to address it?

Gillikin, C., Habib, L., Evces, M., Bradley, B., Ressler, K. J., & Sanders, J. (2016). Trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms associate with violence in inner city civilians. Journal of psychiatric research, 83, 1-7.

http://chicagopolicyreview.org/2017/06/02/breaking-the-cycle-of-inner-city-violence-with-ptsd-care/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5107154/

https://www.thoughtco.com/hood-disease-is-a-racist-myth-3026666

Is All Psychopathy Bad?

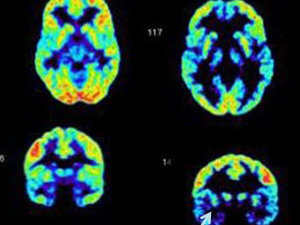

This question arose after an interesting discovery from neuroscientist Dr. James Fallon. Dr. Fallon’s studies involved Alzheimer’s and brain scans of serial killers/psychopaths through Positron Emission Tomography “PET” imaging. The scans of serial killers sparked an interest and led to more studies, this time a control was involved and Dr. Fallon’s brain scan was part of the control. It wasn’t until this that he discovered he is a psychopath.

(Left brain scans are of Dr. Fallon’s son and this is what a normal brain scan looks like. The brain scans on the right belong to Dr. Fallon and you can see that the orbital cortex is dormant. Photo courtesy of James Fallon and NPR's Barbara Hagerty.)

A history of violence was later revealed by Dr. Fallon’s mother that includes descendants like Thomas Cornell (hung for murdering his mother) and the infamous Lizzie Borden (acquitted for the murder of her two parents).

This of course led to further research and most of the studies were conducted on the “12 genes related to aggression and violence.” (Hagerty, 2010). Out of the 12 genes, the MAO-A (monoamine oxidase A) a.k.a. the “warrior gene,” caught his attention “because it regulates serotonin in the brain” which is known as a calming agent that affects one’s mood. (Hagerty, 2010). “Scientists believe that if you have a certain version of the warrior gene, your brain won’t respond to the calming effects of serotonin.” (Hagerty, 2010). Additional studies conducted by other researchers led to the nature v. nurture effect that suppresses the MAO-A gene. The research determined that children with the warrior gene that were abused and/or experienced significant traumatic moments sparked the warrior gene, but children with the warrior gene that were brought up in a positive environment did not become violent psychopathic killers. An example of this is none other than Dr. Fallon.

Well, the PET scans, PCL-R along with Dr. Fallon’s therapist indicate that he is a true psychopath, but he is not a serial killer – so is all psychopathy bad?

Let’s think about this one with an open mind the way Dr. Fallon did. In one of Dr. Fallon’s live presentations at the World Science Festival that can be viewed through YouTube, he fearlessly explored this inquest.

Dr. Fallon asked his audience a couple of questions: do you really want a surgeon that is too emotional/empathic or do you want someone that is more detached from all the feelings and more focused on performing the calculative surgery? Do you want a green beret that gets emotional or one that can go in and complete the mission successfully? Do you want a CEO that doesn’t want to win and make the big bucks?

All of this sparked a new way of thinking and that not all psychopaths are monsters or serial killers. A good depiction of this is the film “I Am Fishead,” which revealed the studies from Paul Babiak and Robert Hare which explored the corporate psychopath based on their research and book “Snakes in Suits.” They derived that the corporate psychopath may not be easy to get along with since they lack empathy, they’re charming, egotistical, and they are manipulative to name a few (20 total traits).

(Photos courtesy of pixabay.com)

These corporate psychopaths do not kill (well, at least that we know of), and they may be horrible team players, but they do play a big role in business economy.

All in all, research on the intricacy of psychopathy is still in its infancy and we hope to find more answers as research continues.

Not all bad is bad and not all good is good.

References:

Hagerty, Barbara Bradley. (2010, 29 June). A Neuroscientist Uncovers a Dark Secret. NPR. Retrieved December 7, 2018, from https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=127888976

Hare Psychopathy Checklist. The Gale Encyclopedia of Mental Health. . Retrieved December 01, 2018 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/hare-psychopathy-checklist

Vortruba, Mishba, and Dejcmar, Vaclab. (2011, 11 Sep.) I am Fishead. Retrieved November 26, 2018, from http://www.fisheadmovie.com/watch1

World Science Festival. (2014, 21 Oct.) The Moth: Confessions of a Pro-Social Psychopath – James Fallon. YouTube. Retrieved December 8, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fzqn6Z_Iss0

ZeitgeistMinds. (2014, 16 Sep.) James Fallon, Neuroscientist - A Scientist's Journey Through Psychopathy. YouTube. Retrieved December 7, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOjykLQAdaE

Separation beyond Borders

Separation beyond Borders

It was September 12, 2011 when I left my home country and settled in another. 7 years have passed and I have never been more thankful to Canada for allowing us to have the life that we have now. At the beginning, I questioned my parent’s decision but every time I ask, they would reply “we did it for you”. It took me while before I could have understood what they meant. Now, I wouldn’t change it for anything.

As an immigrant myself, I do know the hardships that come with leaving your home and starting a new life. However, my situation was clearly different from those who are fleeing their countries to save their lives and their families. For a few months now, I have been watching stories about families being separated under the newly imposed Zero Tolerance Immigration Policy of President Trump. Looking at the story from both sides, I could understand the logic between the policy as it aims to protect its border, its laws, and citizens. However, I do feel that the forcible separation of families pose traumatic effects on the development of children and family relationships.

Poverty is one of the biggest factors for immigration. Families are leaving their home countries to seek better lives in thriving countries such as the United States. According to Blair and Raver (2012), “it is well established that the material and psychosocial contexts of poverty adversely affect multiple aspects of development in children” (p. 309-318). Families have risked their lives to ensure a better future for their children but they have experienced the opposite. As reported by The Intercept (2018), “children separated from their parents are at a higher risk of developing long-term health problems from toxic stress”. Aside from health factors, trauma can impact an individual’s mental, emotional, and psychological aspect (Bartol and Bartol, 2016). Traumatic experiences in childhood such as family separation can lead to adverse effects such as violence and delinquency (Thornberry, Smith, Rivera, Huizinga, and Stouthamer-Loeber, 1999).

I have brought up this topic to give my opinion on both sides of the story. To gain entry and residence in another country, one needs to go through the legal process. At the same time, is it justifiable to punish children and parents by separating them? Instead of resorting to unethical means, we should consider a solution that will benefit both sides. Before we do, there should be public discussion regarding the pros and cons of separating families before passing the zero tolerance immigration policies. With that, I do believe that separation goes beyond borders.

Reference

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2016). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach. 11th Edition. Boston: Pearson.

Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2012). Child development in the context of adversity: Experiential canalization of brain and behavior. American Psychologist, 67, 309–318.

The Intercept (26 Aug 2018). Children separated under Trump’s “Zero Tolerance” Policy say their trauma continues. Retrieved Dec 9, 2018 from https://theintercept.com/2018/08/26/children-separated-under-trumps-zero-tolerance-policy-say-their-trauma-continues/

Thornberry, T. P., Smith, C. A., Rivera, C., Huizinga, D., and Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (1999). Family Disruption and Delinquency. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, 1-5.