CJ 720 Trauma & Crisis Intervention Blog

Controlled Substances For PTSD

Over the decades, psychiatrists have prescribed numerous medications for those suffering from PTSD. More recently, scientists have been curious as to the effects of using psychedelics in attempting to treat Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. The drug professionals are most curious about is methylenedioxymethamphetamine, or MDMA. As with all other medications or brain-altering substances, it is encouraged to seek therapy while taking MDMA to treat one's PTSD. The drug has been shown to reduce fear, increase social engagement and openness, increase empathy and compassion, increase emotionality, and many other benefits (Morland, 2024)

Understandably, there are some fears surrounding the use of substances such as MDMA due to their high addiction rates. This is why it is recommended to only take these substances under a controlled environment where patients can be monitored and the treatment can be stopped if the treatment is beginning to harm the patient or if negative effects are beginning to take shape. Another issue patients may have is that these substances can be quite expensive. They can range from $600 to $8,000 (Olmstead, 2023). Health insurance does not cover these procedures yet as they have not officially hit the market and research is still in progress.

There is a lot more research that needs to be done when considering the long-term effects on the brain for the users of MDMA. For many years the drug has been banned from public consumption and mainly used as a "party drug". However, more and more medical uses have been found for the drug and others which are known to alter one's emotions and to make individuals more easygoing and open to the outside world. Scientists are also looking into using the drug to assist with the treatment of anxiety, substance abuse, and eating disorders. Individuals who wish to seek this type of treatment should speak with their current psychologist and discuss if these types of substances could benefit them or if they are the right type of candidate for further research studies.

References:

Morland, L., & Wooley, J. (2024, March 28). Va.gov: Veterans Affairs. Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy for PTSD. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/txessentials/psychedelics_assisted_therapy.asp#four

Olmstead, K. (2023, September 13). New PTSD treatments offer hope, yet people seeking help should exercise caution. RTI. https://www.rti.org/insights/new-ptsd-treatments-offer-hope-with-caution

Introducing Psychological First Aid Techniques to First Responders

Introducing Psychological First Aid Techniques to First Responders

One of my favorite assignments in this class has been the film review project. For this assignment we were tasked with picking a documentary to watch and analyzing the goal of the documentary. I chose to watch and review the documentary Counselors Responding to Mass Violence Following a University Shooting: A Live Demonstration of Crisis Counseling was created by the American Counseling Association and published by Alexander Street. In this film we saw a presentation about a fictional school shooting at a college and techniques mental health professionals use in the immediate aftermath and a follow up session a month later with one of the survivors. The techniques demonstrated were Psychological First Aid (PFA) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Psychological First Aid is the technique used in the immediate aftermath of the incident and stood out to me as a powerful tool. While there were a lot of documentaries to choose from, I hope at some point everyone in the class can dedicate some time to watching this.

In this fictional scenario, the presentation shows the use of Psychological First Aid with two different survivors of a mass shooting on a college campus. One of the survivors is a bit more visibly shaken, as she heard the gunshots and saw bodies on the ground. The presenters of this scenario then begin to use Psychological First Aid techniques with the survivor. They first begin with helping the survivor return their breathing to normal by introducing the box breathing exercise to them. This breathing method works by having the person breath in through their nose for four seconds, holding that air in their lungs for four seconds and then releasing that air for four seconds. Repeating this method multiple times helps activate the bodies parasympathetic nervous system after a stressful situation.

The next method of Psychological First Aid the presenters use is asking the survivor to describe five non-distressing objects in the room they are in. In doing this, the survivor became more grounded back to reality and into the present situation she was in. To continue grounding the person back to reality, the presenters then had her describe the things she can feel. The survivor went on to express that she could feel the chair she was sitting in, her jeans on her legs and her feet tapping the ground. One last technique they used was having the survivor describe all the feelings she was currently experiencing.

In both scenarios with survivors, the mental health specialists never directly asked the person to describe what they just witnessed and experienced. Doing so could have a negative impact on the long-term effects of surviving this. They let the survivor decide what and how much information they wanted to discuss. All these methods used in Psychological First Aid are extremely useful and easy to implement while working with a survivor or witness to such a traumatic event.

While in this fictitious scenario the mental health professionals were on scene not too long after the event occurred, I wonder how realistic that is in everyday situations. The fictitious scenario of a mass shooting on a college campus is certainly something we can expect a massive response from all sorts of agencies- including mental health professionals. I sadly doubt that there are similar resources readily presented to those who witness something equally traumatic like a stabbing, fatal car accident or fatal fire. I am aware that in the city of Boston the Boston Police have a partnership with the Boston Medical Center’s Boston Emergency Services Team (BEST). These co-response clinicians ride along with officers and respond to calls that deal more with individuals who are in some sort of mental health crisis in hope to avoid the need to arrest the person. There are also currently only 12 of these co-response clinicians on staff, meaning that there may not always be access to someone with this specialty.

As mentioned, the techniques and methods of Psychological First Aid are easy to implement in real-life situations in the moments after the incident occurs. More likely than not, first responders to scenes will be without a mental health professional. Having all first responders familiar with Psychological First Aid methods would be extremely beneficial. Especially giving them an understanding that sometimes-asking direct questions about what someone just survived or witnessed right in the first moments after it happened may have a long-term negative impact on the trauma they endure from the incident.

Counselors Responding to Mass Violence Following a University Shooting: A Live Demonstration of Crisis Counseling. . (2014).[Video/DVD] American Counseling Association. Retrieved from https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/counselors-responding-to-mass-violence-following-a-university-shooting-a-live-demonstration-of-crisis-counseling

How To Think When Interacting With Justice Impacted Youth

Youth justice is an essential area of concern for the criminal justice system that is often not given enough attention (Rousseau, 2024). Trauma and crisis related issues involving youth are far more common than society perceives, and the current systems in place, are not equipped to effectively aid justice-impacted youth (Rousseau, 2024). It is important to remember that there are fundamental differences between how youth and adults react to trauma, and as a result, there are two significant considerations that practitioners should keep in mind when interacting with justice impacted youth. Incorporating these suggestions into daily practice will ensure that proper and effective treatment is administered.

The first consideration to keep in mind is that youth often don’t openly disclose trauma that’s affecting them. Youth do not openly discuss the traumatic experiences of their lives, which can act as a barrier for both diagnosis and treatment (van der Kolk, 2014) - it is impossible to effectively administer treatment if we are unaware of what we are treating. This lack of forthcomingness should not be viewed as youth being intentionally “difficult”, but a consequence of them experiencing trauma at such a young age. Studies have shown that early trauma can affect the development of the prefrontal cortex, which causes increased sensitivity to physical and psychological environments (Rousseau, 2024). Keep in mind that the resulting changes to the prefrontal cortex can lead some youth to become hypersensitive to stressful stimuli, unable to self-regulate emotions, or have elevated levels of fear or anxiety (Rousseau, 2024). Those who interact with which justice impacted youth need to recognize that their demeanor and lack of transparency is a natural part of their reaction to trauma, and therefore interactions should be adapted accordingly.

Secondly, practitioners should recognize that due to a lack of openness on the part of youth, misdiagnosis is common (van der Kolk, 2014). When working with justice-impacted youth, it is important to look past any previous diagnostic labels since they can be unrepresentative of that individual. False diagnosis can lead to improper treatment, and therefore the underlying issues of that patient, will never be addressed. Diagnoses can stick, meaning that a patient might be destined to an ineffective treatment plan if practitioners don’t look past previous labels. While it’s not suggested to throw out any previous diagnoses, what is important to remember is that based on the nature of how youth respond to trauma as discussed above, practitioners should reasonably question previous diagnosis in order to determine effective treatment plans.

To better integrate trauma informed practices into juvenile justice there are a number of recommendations that can be implemented such as the following;

- Utilize trauma screening and assessment;

- Incorporate evidence-based trauma treatments designed for all justice settings;

- Partner with families and communities to reduce the potential traumatic experience of justice involvement;

- Collaborate across all juvenile justice systems to enhance continuity of care;

- Create and enhance a trauma-responsive environment of care;

- Reduce disproportionate minority contact while addressing the disparate treatment of minority youth (Rousseau, 2024).

In addition to these recommendations, it would be beneficial to recognize that triggers and stressors are different for every youth, and that every aspect of a youth's life can act as a stressor or trigger to their trauma. Since trauma impacted youth can have their entire lives affected by trauma, it is important for professionals working with youth to understand that everyday interactions can pose significant challenges and should therefore adapt their behavior accordingly (Van Der Kolk, 2014).

Additionally, practitioners should remember that reactions to trauma can, and often are different for everyone. Labeling a reaction as “not normal” or “unreasonable” would be an improper trauma-informed practice. While tolerance might not always be easy, it is an essential practice when interacting with trauma impacted youth.

Bibliography

Rousseau, D. (2024). Module 2: Childhood Trauma. Boston University Metropolitan College.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma.

A Brief History of Trauma and PTSD

The word trauma is widely known and its meaning is generally understood. However, it can oftentimes be misused to add dramatic effect to a situation; for example, using the phrase, “That was traumatizing,” when perhaps merely an embarrassing situation occurred. Was it traumatizing? What does it mean to be traumatized? As the American Psychological Association (2024) defines it, “Trauma is an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, crime, natural disaster, physical or emotional abuse, neglect, experiencing or witnessing violence, death of a loved one, war, and more.” When emotional responses such as shock, flashbacks, denial, and physical symptoms such as headaches or nausea persist well after the occurrence of an event, a person is likely suffering from trauma.

What may be less commonly known is the history of the word trauma. Trauma is derived from the Greek word τραῦμᾰ, or traûma, meaning “wound,” with roots dating back to the mid-1600s (Kolaitis et al., 2017). Although the word was originally used in reference to a physical wound, it is now more commonly used to refer to an emotional wound. Let’s look at the year 1861, the beginning of the American Civil War when terms such as “soldier’s heart” and “nostalgia” were used when referring to a soldier's response to traumatic stress. Fast forward 53 years to the beginning of World War I. During this time, the term “shell shock” was introduced to describe the physiological responses that soldiers were experiencing as a direct result of heavy explosives. As noted in Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services (2014), “Even with a more physical explanation of traumatic stress (i.e., shell shock), a prevailing attitude remained that the traumatic stress response was due to a character flaw.” At this time, Charcot, Janet, and Freud were articulating that the symptoms that soldiers were experiencing were a direct result of psychological trauma. However, by the year 1939 and the next World War, this information was still falling on deaf ears, as military recruits were being screened to keep out any “who were afflicted with moral weakness.” However, advancements in treatment were being introduced, including allowing soldiers to rest from “battle fatigue.” Talk therapy emerged during the Korean and Vietnam wars, between the years of 1950 and 1975.

Though it took longer than it should have to come to the realization, we now know that there is no single definition of trauma. “The ways we are exposed to trauma are vast, and the individual's response to it is personal. Cultural differences, protective factors, and sense of self can all cause very different outcomes for two people witnessing the same event (Rousseau, 2024, Module 1: Introduction to Trauma).” As van der Kolk expresses in The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in The Healing of Trauma (2014, p. 19), it was not until 1980 that the formal diagnosis of PTSD was developed; an effort made by a group of Vietnam veterans and New York psychoanalysts, Chaim Shatan and Robert J. Lifton. Before this, individuals suffering from the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, most of those war veterans, were being unsuccessfully diagnosed with alcoholism, substance abuse, depression, mood disorder, and schizophrenia. Subsequently, they were being treated with the wrong types of medications, and the wrong forms of therapy. Now, almost 45 years later, we also know that there are many different forms of care available for addressing the impact of trauma, including pharmacotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, exposure therapy, EMDR, neurofeedback approach, internal family systems therapy, yoga, mindfulness, theater, emotional freedom technique, service dogs, and gender-responsive approaches. We also understand that the symptoms of PTSD are very real, and are in no way due to “moral weakness.”

References

American Psychological Association. (2024). Trauma. Retrieved from, https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma

Kolaitis, G., & Olff, M. (2017). Psychotraumatology in Greece. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5632764/

National Library of Medicine. (2014). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services: Appendix CHistorical Account of Trauma. Retrieved from, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207202/

Rousseau, D. (2024). Boston University Metropolitan College, Module 1: Introduction to Trauma. https://onlinecampus.bu.edu/ultra/courses/_127887_1/cl/outline

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in The Healing of Trauma. (1st edition). Viking Penguin.

Yoga – A Therapeutic Approach for Addressing Trauma

Written by Bessel van der Kolk in 2014, The Body Keeps the Score: The Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma is a New York Times bestseller that looks at trauma and its impact on reshaping the brain, mind, and body.

Part five of this novel, titled “Paths to Recovery”, introduces the audience to a number of therapeutic ways in which individuals address trauma in hopes of healing from their traumatic experiences. This may include “finding a way to become calm and focus, learning to maintain that calm in response to images, thoughts, sounds, or physical sensations that remind you of the past, finding a way to be fully alive in the present and engaged with the people around you, and not having to keep secrets from yourself, including secrets about the ways that you have managed to survive” (van der Kolk, 2014). One in particular stood out which will be the focus on this blog post and that is yoga.

In The Body Keeps the Score: The Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, van der Kolk highlighted the impact that mediation has on the brain, specifically yoga. When an individual alleviates the muscle tension in their body, this allows the individual to relax and feel a sense of calmness. Individuals who are experiencing trauma may feel tense or numb because of the trauma that they endured or still continue to endure (van der Kolk, 2014). However, yoga allows these individuals to feel connected to their bodies again. Additionally, yoga therapy is designed to regulate an individual’s arousal and control their physiology (van der Kolk, 2014). Van der Kolk found in a study that ten weeks of yoga reduced PTSD symptoms in individuals who previously attempted to use medications to reduce PTSD but failed (van der Kolk, 2014). In order to relax the mind and heal from trauma, mediation is key.

A 2022 study done by the Cleveland clinic looked at 64 women who were living with chronic, treatment-resistant PTSD (“How Yoga Can Help Heal Trauma”, 2022). The researchers decided to split the women in two groups for them to participate in: trauma-informed yoga or women’s health education. 52% of women no longer met the criteria for PTSD after participating in the yoga trial while only 21% of women no longer met the criteria for PTSD after participating in the education trial (“How Yoga Can Help Heal Trauma”, 2022). Trauma informed yoga is designed to make you feel safe and relaxed. By participating in this, individuals are more likely to feel in control of their body and mind rather than a stranger in their own body and mind (“How Yoga Can Help Heal Trauma”, 2022).

Yoga also plays a major role in prisons. Most incarcerated individuals face feelings of anxiety, stress, and trauma as they are locked in cells for a long period of time. Written by Dragana Derlic, A Systematic Review of Literature: Alternative Offender Rehabilitation—Prison Yoga, Mindfulness, and Meditation is an article that focuses on the importance of yoga, mindfulness, and mediation in order to reduce recidivism and increase the likelihood of rehabilitation (Derlic, 2020). The initiation of yoga programs in prisons is designed to reduce negative thoughts, create a sense of relaxation, strengthen inmates’ attitudes, and show them that there are people out there that still care about them and their health. Not only does yoga reduce stress, anxiety, and trauma, but yoga also plays a vital part in improving an individual’s physical and mental health (Derlic, 2020).

References

Derlic, D. (2020). A systematic review of literature: Alternative offender rehabilitation—prison yoga, mindfulness, and meditation. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 26(4), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345820953837

“How Yoga Can Help Heal Trauma” (2022). Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved from https://health.clevelandclinic.org/trauma-informed-yoga

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York. Penguin Books.

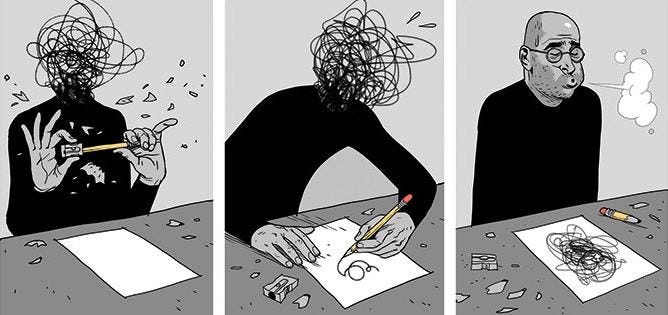

Art Therapy for PTSD

When it comes to trauma, there are different outlets that help with the recovery process. One way of processing is through expressing and finding peace. Art therapy offers a unique and powerful avenue for self-discovery and healing by providing an innovative approach to mental health and emotional well-being. According to the American Art Therapy Association, “Art Therapy is an integrative mental health and human services profession that enriches the lives of individuals, families, and communities through active artmaking, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psychotherapeutic relationship” (2017). There are many creative means to art therapy such as, “drawing, painting, coloring, collage, and sculpture” (Fabian, 2019). For individuals who live with PTSD, art therapy can help enhance emotional expression by having a safe outlet when it is difficult for them to verbalize their feelings.

Art therapy is usually led by licensed art therapists who help guide those who have had traumatic events, such as those with PTSD, through the creative process. During the sessions, the therapists use different exercises that allow free expression of the individual’s goals and needs. The clients are encouraged to discover their feelings and experiences through their specified art medium. With the therapists ongoing support and comprehension, they help the client expand a deeper perception of their inner selves (Fabian, 2019). According to Van der Kolk, “there are thousands of arts, music, and dance therapists who do beautiful work with abused children, soldiers suffering from PTSD, incest victims, refugees, and torture survivors, and numerous accounts attest to the effectiveness of expressive therapies (p. 260, 2014). Through art therapy, therapists “enable clients to grow on a personal level through the use of artistic materials in a safe and convenient environment” (Hu et al, 2021).

This form of therapy offers a beneficial and balancing approach to managing PTSD. By opening the power of creativity, individuals can find new ways to process their trauma, gain insight, and move toward healing and recovery. Art therapy helps with reducing anxiety and stress by having a calming and meditating aspect which allows the clients to feel comfortable. The art creates a deeper understating of their feelings and heal from the traumatic experience which creates a sense of control and resilience. By working with a therapist who is trained and certified, this can help build a therapeutic relationship with the client which would allow them to participate and be more open with their experiences (Good Therapy, 2024).

Bedi, S. (2017, September 18). My experience with art therapy!. Medium. https://medium.com/@saniyabedi05/my-experience-with-art-therapy-2124afc9f2f7

Fabian, R. (2019, August 13). How art therapy can heal PTSD. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/art-therapy-for-ptsd#PTSD,-the-body,-and-art-therapy

Hu, J., Zhang, J., Hu, L., Yu, H., & Xu, J. (2021). Art Therapy: A Complementary Treatment for Mental Disorders. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 686005. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686005

A therapist explains why we shut down when flooded with big emotions. UnityPoint Health. (2024). https://www.unitypoint.org/news-and-articles/a-therapist-explains-why-we-shut-down-when-flooded-with-big-emotions#:~:text=Risk%20of%20Addiction%2C%20Self%2DHarm,negatively%20impact%20a%20person’s%20health.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). Language: Miracle and Tyranny. In The Body Keeps Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (pp. 248-266). essay, Penguin Books.

What is art therapy?. American Art Therapy Association. (2024, January 17). https://arttherapy.org/what-is-art-therapy/

Using Horror as a Therapeutic Tool for Trauma and Trauma Disorders

In the field of trauma and crisis intervention, innovative approaches to therapy are constantly being explored to enhance treatment outcomes. One emerging and somewhat unconventional method involves the use of horror—through movies, video games, and thrill attractions—as a therapeutic tool for individuals dealing with trauma and trauma-related disorders. While this approach may seem counterintuitive, the potential benefits of engaging with horror media in a controlled environment offer intriguing possibilities for trauma recovery.

The Psychology of Horror: Facing Fears in a Safe Space

Horror media, whether it’s a spine-chilling movie, a tension-filled video game, or an adrenaline-pumping haunted house, taps into deep-seated fears and anxieties. For many, these experiences are thrilling and even enjoyable, providing a way to confront and process fear in a controlled setting. This concept aligns with the therapeutic principle of exposure therapy, which involves gradually and safely exposing individuals to anxiety-provoking stimuli to reduce fear responses over time (Foa & Kozak, 1986).

Exposure Therapy in a Different Light

Exposure therapy has long been a cornerstone in treating anxiety disorders and PTSD. The underlying principle is that repeated, controlled exposure to the source of fear or trauma can help desensitize individuals and reduce avoidance behaviors. Horror media can serve a similar function by allowing individuals to confront fear in a context where they know they are not in actual danger. This controlled exposure can help trauma survivors regain a sense of agency and control, which is often lost after traumatic experiences (Pittman & Karle, 2015).

The Therapeutic Potential of Horror Media

Emotional Processing and Catharsis

Horror movies and video games often evoke strong emotional responses, ranging from fear and anxiety to relief and exhilaration. This emotional rollercoaster can serve as a form of catharsis, helping individuals process complex emotions associated with their trauma. Research suggests that horror fans may use this genre as a way to confront their fears and anxieties in a safe, manageable way, which can lead to a sense of mastery over these emotions (Clasen, 2017).

Re-experiencing and Reclaiming Narrative

For trauma survivors, horror media can provide a unique opportunity to re-experience fear and terror within a narrative framework. Unlike real-life trauma, where individuals often feel helpless, engaging with horror media allows for a controlled re-experiencing of fear, where the individual can pause, stop, or disengage at any time. This can empower trauma survivors to reclaim their narrative and develop a new relationship with fear (Scrivner et al., 2021).

Social Connection and Shared Experience

Horror is often a shared experience, whether watching a scary movie with friends or discussing a horror game online. This shared experience can foster social connection, reducing feelings of isolation that often accompany trauma. Group therapy sessions incorporating horror media could potentially strengthen group cohesion and provide a shared platform for discussing fears and coping strategies (Scrivner, 2020).

Clinical Considerations and Ethical Implications

While the use of horror media as a therapeutic tool is intriguing, it is essential to consider the clinical and ethical implications. Not all individuals may benefit from this approach; for some, horror media could exacerbate symptoms or trigger distressing memories. Therefore, careful screening and individualized treatment planning are crucial. Clinicians should also be trained to handle potential negative reactions and provide appropriate support.

Moreover, this approach should be seen as a complementary tool rather than a standalone treatment. Integrating horror media into a broader therapeutic framework that includes established methods like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) may offer the best outcomes for trauma survivors (Shapiro, 2017).

The use of horror as a therapeutic tool for trauma and trauma-related disorders is a novel approach that challenges conventional treatment paradigms. By leveraging the psychological mechanisms of exposure, emotional processing, and narrative control, horror media has the potential to help trauma survivors confront and master their fears in a safe, controlled environment. While more research is needed to establish the efficacy of this approach, it offers a fascinating avenue for expanding the therapeutic toolbox in trauma and crisis intervention.

References:

Clasen, M. (2017). Why Horror Seduces. Oxford University Press.

Foa, E., & Kozak, M. (1986). Emotional Processing of Fear: Exposure to Corrective Information. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 20-35.

Pittman, C., Karle, E. (2015). Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and Worry. New Harbinger Publications.

Scrivner, C. (2020). The Psychology of Horror: Why Scary Movies and Thrilling Attractions Are Good for You. Journal of Media Psychology, 32(2), 85-94.

Scrivner, C., Johnson, J., Kjeldgaard-Christiansen, J., & Clasen, M. (2021). Pandemic Practice: Horror Fans and Morbidly Curious Individuals are More Psychologically Resilient During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110397.

Shapiro, F. (2017). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. Guilford Press.

Tetris for Trauma – Unconventional Approaches to Trauma Prevention

When looking for a blog post subject, I decided that I wanted to learn more about the latest updates in trauma care. As we have seen in class and in our readings, trauma care has changed significantly over the last few decades. For example, in van der Kolk’s book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body, he discusses an old belief that in the case of father-daughter incents, “incestuous activity diminishes the subject's chance of psychosis and allows for a better adjustment to the external world”. This is clearly not an opinion that we would take today and demonstrates the progress made in psychological research.

So what are some of the newer ideas about trauma? One of the ones that caught my attention was playing “Tetris” as a potential trauma prevention. This idea was presented in the article “Can playing Tetris help prevent PTSD if you’ve witnessed something traumatic?”(Bressington & Mitchell, 2024). It seems to have first been proposed in 2009 by Oxford University psychologists. They suggest that playing a visuospatial game like “Tetris”, within 30 minutes after a traumatic event may disrupt the formation of sight and sound memories related to the traumatic event. This is because trauma flashbacks are sensory-perceptual, visuospatial mental images. Therefore, when a visuospatial game like “Tetris” is played within the time usually reserved for memory consolidation, it fights for the brain’s resources and leads to reduced flashbacks (Holmes et al., 2009).

While this research was done over a decade ago, more recent research has also shown success in using “Tetris” to prevent PTSD flashbacks as well as potentially reducing depression and anxiety in combat veterans (Butler et al., 2020). Additionally, in a randomized controlled trial, “Tetris” was found to be an effective intervention to reduce intrusive memories overall and lead to declined intrusive memories for emergency department patients who had experienced motor vehicle crashes. Patients found this intervention easy, helpful, and minimally distressing (Iyadurai et al., 2018). Another study suggested the use of “Tetris” and other verbal word games to reduce intrusive memories (Hagenaars et al., 2017).

Although this research has not been implemented into most people’s mental health practices in the medical community, it is frequently offered as advice to people seeking help after a traumatic situation on Reddit. An example presented in the Bressington and Mitchell article is from a Reddit poster in Sydney, Australia looking for advice on dealing with a traumatic situation (saltyisthesauce, 2024). Additionally, if you just type in “Tetris for PTSD” in the Reddit search, numerous posts advocating for “Tetris” playing can be found, especially for visually disturbing traumatic situations. While obviously, this is not research and not normally something I would cite, for this blog post in exploring the topic, I thought it would be worth noting as it demonstrates that the idea has spread outside of the research world and has some acceptance in the general public.

For my own opinion on the subject, I really like the idea of “Tetris” as a potential trauma prevention. One of its main draws is its accessibility. “Tetris” is freely available to anyone who owns a phone or computer. This makes it much more accessible than most trauma treatments such as medications or therapy. This also means it is more accessible financially and for groups who may not traditionally utilize healthcare. Additionally, it presents a way to prevent PTSD in the first place, as its mechanism of action is to interrupt memory formation instead of responding to the trauma after the fact. This could have important implications for the future of trauma research as preventing trauma from occurring is better than having to deal with the side effects after the fact. Therefore, after a traumatic event, the idea of playing “Tetris” presents an easily actionable, potentially beneficial, step instead of ruminating about the traumatic event. I’m excited to see future research on this topic and hope to see more unconventional PTSD treatments like it in the future.

Citations

Bressington, D., & Mitchell, D. A. (2024, April 15). Can playing Tetris help prevent PTSD if you’ve witnessed something traumatic? The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/can-playing-tetris-help-prevent-ptsd-if-youve-witnessed-something-traumatic-226736

Butler, O., Herr, K., Willmund, G., Gallinat, J., Kühn, S., & Zimmermann, P. (2020). Trauma, treatment and Tetris: Video gaming increases hippocampal volume in male patients with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 45(4), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.190027

Hagenaars, M. A., Holmes, E. A., Klaassen, F., & Elzinga, B. (2017). Tetris and Word games lead to fewer intrusive memories when applied several days after analogue trauma. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup1), 1386959. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1386959

Holmes, E. A., James, E. L., Coode-Bate, T., & Deeprose, C. (2009). Can Playing the Computer Game “Tetris” Reduce the Build-Up of Flashbacks for Trauma? A Proposal from Cognitive Science. PLoS ONE, 4(1), e4153. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004153

Iyadurai, L., Blackwell, S. E., Meiser-Stedman, R., Watson, P. C., Bonsall, M. B., Geddes, J. R., Nobre, A. C., & Holmes, E. A. (2018). Preventing intrusive memories after trauma via a brief intervention involving Tetris computer game play in the emergency department: A proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Molecular Psychiatry, 23(3), 674–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.23

saltyisthesauce. (2024, April 13). What just happened at Bondi junction? [Reddit Post]. R/Sydney. www.reddit.com/r/sydney/comments/1c2uo3p/what_just_happened_at_bondi_junction/kzd8t6u/

Culinary Therapy (a.k.a. Cooking Therapy)

While the notion of food as therapy may conjure imaginings of your favorite pint of ice cream and a spoon, culinary therapy is, in fact, a therapeutic technique that can help patients with relationship, psychological and behavioral disorders. Dr. Michael Kocet, chair of the Counselor Education Department for the Chicago School, defines culinary therapy as “the therapeutic technique that uses arts, cooking, gastronomy, and an individual’s personal, cultural, and familial relationship with food to address emotional and psychological problems faced by individuals, families, and groups. Culinary therapy involves an exploration of an individual’s relationship with food and how food impacts relationships, as well as psychological well-being and functioning.” (Vaughn, 2017)

Cooking as a modality for therapy can also be used in a less clinical format. In a separate article on cooking therapy, Debra Borden, licensed clinical social worker, uses cooking practices with clients to connect them with the specific “opportunities and assets” that cooking offers, namely: “metaphor, mindfulness, and mastery. The metaphors are sometimes obvious—there’s nothing subtle about kneading frustrations into bread dough—but Debra specializes in encouraging patients to see each act and ingredient as symbolic of something deeper, a kind of concentration that encourages that second M, mindfulness. And if you can pay attention to the metaphors and learn something new about yourself you get that sense of mastery: a little thrill of accomplishment that reinforces your belief in your own competence and skill.” (Romanoff, 2021)

While practitioners of culinary therapy have varying approaches, the tasks and activities associated with meals: planning, preparing, serving, eating and clean-up each serve as opportunities to re-instate routine, order, even social reintegration and trust for the individual, a family, or other group.

Behavioral scientists continue to explore and validate cooking interventions for positive psychosocial outcomes. A 2018 Health Education & Behavior Journal article, Psychosocial Benefits of Cooking Interventions: A Systematic Review, documented and research-validated positive outcomes that include:

- Confidence and Self-Esteem: “participation in baking sessions led to improved self-esteem, primarily as a result of increased concentration, coordination, and confidence.”

- Socialization: “There was some evidence that socialization benefits might extend beyond the cooking interventions, as some participants continued to report improved social interactions at home and with family, and they continued to prepare meals as household teams even 6 months later.”

The researchers concluded, “Despite varying types of measurement tools and different patient populations, these studies reported a positive influence associated with participation in cooking interventions on psychological outcomes, including self-esteem, social interaction, as well as decreased anxiety, psychological well-being, and quality of life.” (Farmer, Touchton-Leonard, & Ross, 2018)

A specific study of meal preparation and cooking group participation concluded “that meal prep and cooking groups may be significant for helping psychiatric clients achieve and maintain appropriate mood and hygiene for independent living skills.” (Garcia & Privott, 2023)

Whether the therapy is individual or group-oriented, meal preparation and food-oriented tasks can be an effective therapeutic modality to improve psychological, behavioral, and relationship / social disorders.

References

Farmer, N., Touchton-Leonard, K., & Ross, A. (2018). Psychosocial Benefits of Cooking Interventions: A Systematic Review. Health Education & Behavior, 167-180.

Garcia, A., & Privott, C. (2023). Meal Preparations and Cooking Group Participation in Mental Health: A Community Transition. Food Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 85-101.

Romanoff, Z. (2021, June). I Hired a Cooking Therapist to Deal With My Anxiety. bon appetit, pp. https://www.bonappetit.com/story/cooking-therapy.

Vaughn, S. (2017, October). From cooking to counseling. Retrieved from The Chicago School: From the Magazine | Insight: https://www.thechicagoschool.edu/insight/from-the-magazine/michael-kocet-culinary-therapy/

Trauma in the Texas Juvenile Justice System and two Great Therapeutic Programs

Trauma in the Texas Juvenile Justice System

It is widely recognized that children incarcerated in the Texas Juvenile Justice System have often experienced significant trauma before their admission to state schools, halfway houses, and probation systems. The Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) aims to "create an environment where we can help them learn to make decisions, manage their emotions and reactions to stress, and take responsibility for their lives and decisions—in other words, to correct" (Texas Juvenile Justice Department, n.d.). This approach is embodied in the Texas Model.

Many children in the system have faced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which may include having one or both parents incarcerated, being victims of sexual assault, experiencing aggravated assault, death, and various forms of family violence. Most, if not all, of the children incarcerated have at least four ACEs. ACEs are defined as Adverse Childhood Experiences. According to Module 2 of Professor Rousseau’s course, the following ACEs categories are included:

- Alcoholism and alcohol abuse

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Depression

- Drug use

- Heart disease

- Liver disease

- Risk of partner violence

- Smoking

- Suicide

- Overall decline in quality of life (Rousseau, n.d.)

Statistics from the Texas Juvenile Justice Department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that individuals with just one ACE have a 200% to 500% increased chance of attempting suicide. With four ACEs, the risk increases to 2400%, and with seven ACEs, it rises to a staggering 5100% compared to those with no ACEs. In the Texas Juvenile Justice System, "fifty-two percent of our youth in secure facilities have four or more ACEs,” according to a conservative estimate. Breakdown statistics show that about 50% of boys and 87% of girls in the system have four or more ACEs, with 47% of girls having seven or more (Texas Juvenile Justice Department, n.d.).

Given these statistics, it is crucial for the Texas Juvenile Justice Department to focus its correctional and educational efforts on behavioral and mental healing. While it is important to hold these children accountable for their actions, this should be done within a trauma-informed, healing environment. Texas should prioritize rehabilitation through trauma-informed care over punitive measures.

Trauma-informed care in the Texas Juvenile Justice System is essential. Rousseau (n.d.) emphasizes that “Trauma-informed care needs to build on practices, skills, training, and strategies that directly affect the entire juvenile justice continuum of care.” Texas screens incoming child offenders for ACEs to ensure appropriate placement in TJJD facilities.

Here are some examples of trauma therapy programs currently used in TJJD to address behaviors and educate families on coping with past traumatic experiences:

- Aftercare Management

- Anger Management/Conflict Resolution

- Animal/Equine Therapy

- At-Risk Programs

- Border Children Justice Project

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/Treatment

- Community Service/Restitution

- Counseling Services

- Drug Court

- Early Intervention/First Referral

- Educational Programs

- Electronic/GPS Monitoring

- Experiential Education

- Extended Day Program/Day Boot Camp

- Family Preservation

- Female Offender Programs

- Gang Prevention/Intervention

- Home Detention

- Intensive Case Management

- Intensive Supervision

- Life Skills Programs

- Mental Health Services

- Mental Health Court

- Intellectual Disabilities Services

- Mentoring

- Parent Training (for parents)

- Parenting (for juveniles)

- Runaway/Truancy Programs

- Sex Offender Treatment

- Substance Abuse Prevention/Intervention

- Substance Abuse Treatment

- Victim Mediation

- Victim Services

- Vocational/Employment Programs (Texas Juvenile Justice Department, 2024).

This blog will focus on two programs that require additional funding and have shown success with youthful offenders. I will reference a 2024 TJJD findings report from an investigation conducted by the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Attorney’s Offices for the District of Texas. Despite numerous issues within TJJD facilities, efforts are being made to address these problems. The Office of the Inspector General has been established to address criminal acts occurring in TJJD facilities. Access points into and out of the facilities have been taken over to control contraband and improve safety. However, staff violations of rules and policies remain a concern.

The TJJD has reintroduced the BARK therapy program, which involves TJJD becoming a foster home for dogs. According to Woodard (2024), the Gainesville State School Superintendent acknowledges that most juvenile offenders come from traumatic environments. He emphasizes that the TJJD system refers to offenders as "adjudicated" rather than "convicts," recognizing their victimization. The program currently includes sixteen children and six dogs. It teaches offenders to care about something other than themselves and promotes discipline. A quote from a participant reflects the program's impact: “When I first got him, he was kind of shaken up because of where he came from. And I felt that same way – we had that same connection” (Woodard, 2024). Another participant noted, “They say a dog is a man’s best friend and I agree... If I feel down, he will come around and help me out” (Woodard, 2024). The BARK program is noted for having the fewest incidents on campus, indicating its effectiveness in trauma-informed rehabilitation.

Another notable trauma-informed program is the equestrian program formerly located at Tornado Ranch. Known as Trauma-Focused Equine Assisted Psychotherapy or Trauma-Informed Equine Assisted Learning, this program was discontinued due to financial constraints, resources, and departmental priorities. Like the BARK program, it allowed youths to establish empathy, discipline, and love by caring for rescue horses. The program helped participants resolve personal traumas and improved their understanding of themselves and others. The reintroduction of this program would benefit the TJJD system (TJJD, 2018).

To ensure that these children become productive members of society, it is essential to secure funding for these programs. A just society requires a trauma-informed correctional system that supports all its members.

References

Rousseau, P. (n.d.). Module 2: Adverse Childhood Experiences. [Course material].

Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (n.d.). Program Registry - Public Access. Retrieved from https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/programregistryexternal/members/searchprograms.aspx

Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (2024). [Report].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Adverse Childhood Experiences. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/index.html

U.S. Department of Justice. (2024, August 2). Homepage. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/

Woodard, T. (2024, May 20). This high-security juvenile detention center in North Texas just became a foster home for dogs. WFAA. https://www.wfaa.com/article/features/originals/high-security-juvenile-detention-center-texas-became-foster-home-for-dogs/287-7eaf7654-3128-4eaf-8a92-f22892a49dde

Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (2018, September 22). Tornado Ranch has ramped up in the past six months. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/TexasJJD/posts/tornado-ranch-has-ramped-up-in-the-past-six-months-and-now-serves-10-youth-who-p/2147383878916782/?locale=hi_IN