Childhood Trauma & Criminality: How Public Safety and Support Systems Fail Vulnerable Youth

Child abuse is a national safety crisis, with 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the United States being said to experience some kind of child abuse, whether that be physical, emotional, sexual abuse or neglect (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.). The consequences of childhood abuse and trauma have been researched extensively across field of social sciences, psychology, developmental neuroscience and more, as society has begun to realise to extent to which these traumatic experiences in childhood can influence later behaviour and mental health issues. In recent years, studies have examined the rippling effects childhood trauma can have on victims even decades after the victimisation, evidencing how trauma can hinder work success (Paulise, 2023), can detrimentally affect romantic relationships and marital success (Nguyen et al., 2017) and is significantly associated with varying chronic health problems (Afifi et al., 2016). The effects of childhood abuse are unbounded.

Child abuse is a national safety crisis, with 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the United States being said to experience some kind of child abuse, whether that be physical, emotional, sexual abuse or neglect (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.). The consequences of childhood abuse and trauma have been researched extensively across field of social sciences, psychology, developmental neuroscience and more, as society has begun to realise to extent to which these traumatic experiences in childhood can influence later behaviour and mental health issues. In recent years, studies have examined the rippling effects childhood trauma can have on victims even decades after the victimisation, evidencing how trauma can hinder work success (Paulise, 2023), can detrimentally affect romantic relationships and marital success (Nguyen et al., 2017) and is significantly associated with varying chronic health problems (Afifi et al., 2016). The effects of childhood abuse are unbounded.

Criminality and childhood victimisation

Though childhood abuse is a hard to measure hidden phenomenon, the statistics we do have show that children who experience abuse, neglect, or exposure to violence are at higher risk of engaging in criminal activity later in life.

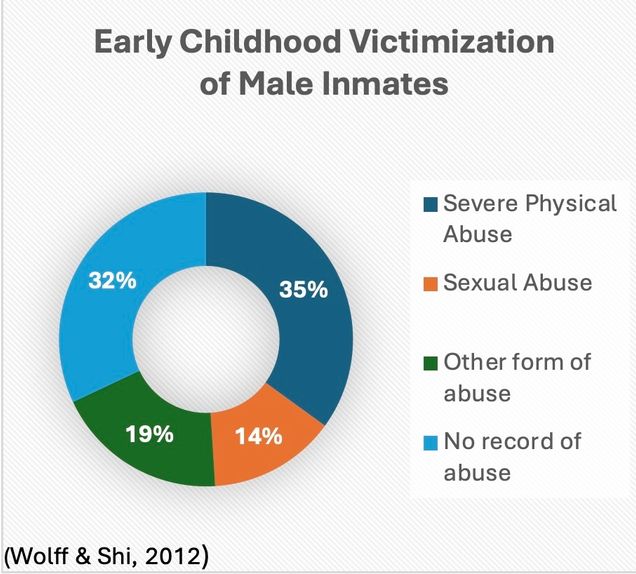

In the U.S., studies have reported as many as 1/6 male inmates having experiences physical or sexual abuse before the age of 18 (Wolff & Shi, 2012) – and this is the low end of the scale. Other studies, such as one by Robin Weeks and Cathy Spatz Widom (1998) for the National Institute of Justice found 68% of the male inmates in their sample reported some form of childhood abuse before the age of 12 (physical, sexual, neglect). Scholars have theorised this is linked to the Cycles of Violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989; Widom & Maxfield, 2001), which claims that adverse childhood experiences of violence, abuse or neglect can cause victims to reproduce this behaviour in their adult lives which often leads to violent criminal behaviour.

In the U.S., studies have reported as many as 1/6 male inmates having experiences physical or sexual abuse before the age of 18 (Wolff & Shi, 2012) – and this is the low end of the scale. Other studies, such as one by Robin Weeks and Cathy Spatz Widom (1998) for the National Institute of Justice found 68% of the male inmates in their sample reported some form of childhood abuse before the age of 12 (physical, sexual, neglect). Scholars have theorised this is linked to the Cycles of Violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989; Widom & Maxfield, 2001), which claims that adverse childhood experiences of violence, abuse or neglect can cause victims to reproduce this behaviour in their adult lives which often leads to violent criminal behaviour.

However, I challenge this idea. Instead, I theorise that childhood victimisation of violence itself does not inherently cause more violence, instead it is the experience of violence within a society that fails to protect, support, or care for vulnerable children that fosters these cycles. This phenomenon should be understood through a lens similar to the social disability model: just as disability does not inherently limit a person, but rather society’s failure to provide adequate support does, it is not abuse alone that leads to violence or criminality. Rather, it is the failure of social systems to intervene, protect, and care for trauma-affected children that perpetuates these outcomes.

Systemic Failures and Their Consequences

When we examine the systems in place to both prevent incidents of child abuse and promote healing among known victims, we can see failures of the system to adequately do so at every step of the way. Many politicians and academics defend these failures by using the hidden nature of abuse as an excuse – but research shows there were an estimated 558,899 instances of recorded child abuse in the US in 2022 alone (National Children’s Alliance, n.d.), thus proving there are countless cases that are known and in need of assistance. But what are the systems in place to support these children? And if they are working, why do we see so many past victims of abuse spiral into criminality?

In my opinion, this is because of three main failures of policy and support services:

- Lack of Access to Mental Health Care: Many children in abusive environments do not receive the psychological care needed to process their trauma, leading to behavioural issues that escalate over time through exacerbation and development of mental health issues caused by lack of appropriate intervention and support.

- Underfunded Social Services: Child welfare systems often fail to provide consistent, long-term support, leaving many children vulnerable. Increased funding and allocation of resources could in the long-term prevent increased criminality among this population, and instead help more victims heal and become citizens who contribute positively to society.

- School and Community Gaps: Schools and communities frequently lack the resources to identify and assist trauma-affected children before they enter the criminal justice system. Training should be compulsory for teachers and community workers to help them identify signs of trauma, and to intervene in trauma-informed ways that benefit the child without retraumatizing them.

Breaking the Cycle: What Can Be Done?

To break the ‘cycle of violence’ and criminality associated with childhood trauma, we must shift our focus from reactive to proactive solutions, by working to ensure that abuse survivors receive the support they need to heal and thrive. This calls for a multi-faceted reformative approach to support procedures and legislative prevention policies, that refocuses its aim to break the socially imposed link between childhood victimisation of violence and adult or adolescent criminality.

- Expanding Trauma-Informed Care must become a priority across a vast range of public systems including child welfare, education, and criminal justice systems. This involves comprehensively training teachers, social workers, law enforcement, and healthcare providers to recognise signs of trauma, and to deal with these situations in ways that do not retraumatise children.

Strengthening Family and Community Support Systems should also be a priority. Government funding should be re-allocated to promote evidence-based programs that target risk-factors for child abuse and have proven to reduce instances of violence. For instance, the program SafeCare which visits parents at home to help promote positive and safe relationships between caregivers and children.

Strengthening Family and Community Support Systems should also be a priority. Government funding should be re-allocated to promote evidence-based programs that target risk-factors for child abuse and have proven to reduce instances of violence. For instance, the program SafeCare which visits parents at home to help promote positive and safe relationships between caregivers and children.- Reforming the Juvenile Justice System would also help to aid trauma-affected youth in a real way instead of simply criminalising them. This could be done through diversion programs that connect with trauma-affected youth who may have encountered the criminal justice system. But instead of providing them with punishment, programs could be focussed on counselling efforts, and mental health support to address the root cause of early criminal behaviour.

- Improving Accessibility to Mental Health Resources would be a vital part of this process. Many trauma survivors – particularly those from marginalized communities – face significant barriers to receiving psychological care, especially in a nation lacking universal healthcare. Instead, systems could be put into place to provide victims with this care through community-based organizations and clinics, or even school based mental health programs – to ensure that children without access to health insurance and adequate health care can still access the tools they need to heal.

- Advocating for Policy Change would work to address systematic failures that prevent the prioritisation of child welfare. This could include allocating more funding for child protective services, improving foster care monitoring systems, and enforcing stricter measures for cases of institutional negligence. By shifting legislative priorities towards prevention and rehabilitation rather than punishment, we can begin dismantling the structural barriers that perpetuate cycles of trauma and criminality.

By addressing the root causes of violent behaviour through trauma-informed care and providing survivors with the tools they need to heal, we can create a future where childhood victimization of violence does not dictate one’s path in life.

Reference list:

Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M., Cheung, K., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., & Sareen, J. (2016). Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health reports, 27(3), 10–18. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26983007/

National Children’s Alliance. (n.d.). National Statistics on Child Abuse. https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/media-room/national-statistics-on-child-abuse/

Nguyen, T. P., Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2017). Childhood abuse and later marital outcomes: Do partner characteristics moderate the association? Journal of family psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 31(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000208

Paulise, L. (2023, June 9). 3 Ways Childhood Traumas Impact Work Productivity and Well-Being. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lucianapaulise/2023/06/09/3-ways-childhood-traumas-impact-work-productivity-and-well-being/

Weeks, R., & Widom, C.S. (1998). Early Childhood Victimization Among Incarcerated Adult Male Felons. National Institute of Justice: Research Preview, U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/fs000204.pdf

Widom, C. S. (1989). The Cycle of Violence. Science, 244(4901), 160–166. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1702789

Widom, C.S., & Maxfield, M.G. (2001). An Update on the “Cycle of Violence”. National Institute of Justice: Research Preview, U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/184894.pdf

Wolff, N., & Shi, J. (2012). Childhood and adult trauma experiences of incarcerated persons and their relationship to adult behavioral health problems and treatment. International journal of environmental research and public health, 9(5), 1908–1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9051908