Institutional Betrayal Trauma and Peer Victimization

” [Institutional courage] is an institution’s commitment to seek the truth and engage in moral action, despite unpleasantness, risk, and short-term cost. It is a pledge to protect and care for those who depend on the institution. It is a compass oriented to the common good of individuals, the institution, and the world. It is a force that transforms institutions into more accountable, equitable, healthy places for everyone.” – Center for Institutional Courage

Bullying as a form of aggressive behavior can elicit traumatic responses in many different populations. The most commonly addressed forms of bullying are school or childhood bullying and workplace peer victimization. Betrayal trauma theory addresses the traumas experienced by victims that are not always clinically recognized as traumatic. There are different types of betrayal trauma such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse committed by a caregiver, cultural betrayal, and institutional betrayal. Peer victimization, or bullying, can play a part in these experiences. Peer victimization on its own is exacerbated by institutional betrayal. Reports of peer victimization often go unaddressed by those in power at schools, and if they are addressed it is not usually an effective response. This ineffectiveness on account of the people and institutions that hold the power to address bullying poses as a form of institutional betrayal; thus leading to many victims of bullying to also experience a second form of trauma in institutional betrayal.

Both peer victimization and betrayal trauma are linked to post-traumatic stress reactions, but neither institutional betrayal nor peer victimization are officially listed in the criteria required for a clinical post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. This has opened up research that questions the clinical implications for people who experience traumas not listed in the PTSD criteria and possible solutions. Institutional betrayal exacerbates peer victimization which shares symptomatology with PTSD; it should be considered for either inclusion of the PTSD diagnosis or grouped with other forms of childhood betrayal trauma to form a new diagnosis.

Peer Victimization and PTSD

Peer victimization in children, commonly called “school bullying,” takes place during sensitive periods of development. PTSD symptoms are often reported in victims of bullying (Idsoe et al., 2012). Bullying is a highly interpersonal event and it is known that experiencing an interpersonal trauma is linked with significantly higher levels of PTSD symptoms compared to other kinds of trauma (Lancaster et al., 2009 as cited in Idsoe et al., 2012). The relationship was originally established in workplace peer victimization, but is branching out towards school bullying. This is important to note because school bullying takes place during adolescence, an important developmental period of biopsychosocial systems. This presumes that bullying may have an adverse effect on biopsychosocial development.

Among the post-traumatic stress symptoms reported by people who have experienced bullying is dissociation. Dissociation is a very common symptom of PTSD. Gušić and colleagues (2016) conducted a study about different types of trauma in adolescence and their relation to dissociation. They found that emotional traumas, like bullying, showed stronger associations with dissociative experiences (DEs). Girls reported both higher levels of DEs and bullying. Betrayal traumas are also a kind of emotional trauma, and research shows that women experience more betrayal traumas than men do (Freyd, 2020). These associations between peer victimization and PTSD argue that the incidents of bullying can lead to symptoms that meet the clinical threshold of distress, for peer victimization to be officially recognized as an inciting traumatic event.

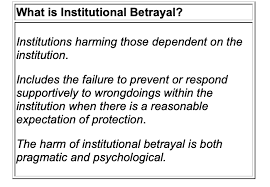

Institutional Betrayal

If peer victimization on its own results in post-traumatic stress symptoms and is perpetuated by academic institutions, then peer victimization is further complicated by institutional betrayal. Institutional betrayal is defined as transgressions perpetrated by an institution upon individuals dependent on that institution, including failure to prevent or respond supportively to transgressions by individuals committed within the context of the institution (Freyd, 2020). Institutional betrayal plays a part in peer victimization as most school bullying takes place in the context of the school by a peer also enrolled at that institution. This betrayal extends further into the institution when a victim’s disclosure is not responded to effectively.

There is relatively limited research on what characteristics define an adult’s response as “helpful or supportive” to an adolescent’s disclosure of bullying (Bjereld et al., 2019). First it is important to acknowledge that, yes, there are preventive and interventive strategies that produce positive outcomes. The problem is presented when school officials (assuming the victims’ parents have attempted effective communication, if they are aware of the bullying) fail to implement these strategic responses. These are similar to some of the responses that survivors of sexual assault receive, such as minimization or invalidation of the incident and a sense of abandonment when no steps are taken to address the issue once disclosed. Bjereld and colleagues’ (2019) study found that teachers often found a student’s disclosure as them misinterpreting the event or debated whether the victim was to blame. Once a student had disclosed and determined that the response was ineffective, they were less likely to report future incidents.

Clinical Implications

The clinical implications of peer victimization and institutional betrayal are apparent in that neither falls under the official PTSD Criterion A requirement. This may lead to multiple obstacles such as an onslaught of diagnoses that impede treatment, incorrect or incomplete treatment, and incorrect or incomplete diagnoses. One of the main uses of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) is for insurance purposes. This allows for affordable treatment, and official recognition and documentation of the outcome of a victim’s experience. Both of these are important in relation to receiving treatment, but also working on easing another betrayal trauma from healthcare institutions. Not being acknowledged by another set of officials who have the power to provide assistance can constitute another institutional betrayal.

Clinical implications may cascade into policy implications as well. Official documentation may also require the school to respond to an incident as effectively as possible, such as amendments to codes of conduct and disciplinary actions. This in turn could reduce the extent of institutional betrayal on a case by case basis, but also work toward resolving the root issue of peer victimization.

Diagnostic Solutions

There are multiple considerations in searching for possible solutions concerning an official diagnosis. There is debate about the limitations of the PTSD diagnosis, especially the constitution of Criterion A. Other commonly explored diagnostic solutions are complex PTSD and developmental trauma disorder (DTD).

Complex PTSD refers to the experience of survivors of prolonged and repeated traumas, and can consist of symptomatology that differs from PTSD (McDonald et al., 2014). While symptoms include the amplification of PTSD symptomatology, survivors of complex PTSD may also experience changes in relationships (i.e., fluctuations between healthy and unhealthy attachment and withdrawal). Bullying is defined as a kind of aggressive behavior involving repeated negative actions over time by a perpetrator against an individual who cannot defend themselves (i.e., a power imbalance) (Idsoe et al., 2012). This supports the notion that peer victimization is not only linked to the current PTSD diagnosis, but common reactions to peer victimization fulfill requirements for a new or revised PTSD criteria implementing consideration of complex PTSD.

DTD is a proposed clinical diagnosis that was previously considered but ultimately denied inclusion in the DSM-5. The American Psychiatric Association’s defense was that the idea that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) could lead to substantial developmental disruptions was more “clinical intuition” than evidence-based fact (van der Kolk, 2014). However, research has shown that ACEs, which include bullying, can have negative effects on brain development. Other research on ACEs have shown that distressing events can lead to symptoms similar to PTSD (Ossa et al., 2019). Previous targets of school bullying are at a higher risk for poor general health and have greater difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships.

In the DSM-5, there are specifications for children under six in the PTSD diagnosis. These include slightly different symptoms or presentation of PTSD symptoms. Van der Kolk (2014) writes that PTSD symptoms along with the specifications for early childhood trauma can be fully explained by a diagnosis of DTD. McDonald and colleagues (2014) conducted a study measuring potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs), and whether these experiences were predictive of a distinct set of symptoms characteristic of DTD. Bullying (physical, relational, verbal, and cyber) was included on the list of PTEs. Results confirmed a substantial amount of distressing life events that occur during childhood and adolescence. They also support future revision of the DSM-5 to include a developmentally-focused diagnosis for PTSD-like symptoms that do not necessarily meet PTSD Criterion A.

Conclusion

Institutional betrayals reach as far as one’s local schools. Peer victimization has been further impacted by institutional betrayal and is a national problem. Reports of peer victimization often go unaddressed, and if they are addressed it is not usually an effective response. This ineffectiveness on account of the people and institutions that hold the power to address bullying poses as a form of institutional betrayal. This leads to many victims of bullying to also experience a second form of trauma in institutional betrayal.

Both peer victimization and betrayal trauma are linked to post-traumatic stress reactions, but neither are officially listed in the criteria required for a clinical PTSD diagnosis. This has led research to explore the clinical implications for people who experience traumas not listed in the PTSD Criterion A requirement, and possible solutions. Possible solutions include three revisions of the DSM-5 to include at least one of the following: 1) a revision of PTSD Criterion A to include traumatic events not currently listed, 2) the addition of complex PTSD, or 3) the addition of a developmentally-focused diagnosis for post-traumatic stress reactions that do not fall under PTSD Criterion A.

References

Bjereld, Y., Daneback, K., & Mishna, F. (2019). Adults’ responses to bullying: The victimized youth’s perspectives. Research Papers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1646793

Freyd, J. J. (2020). What is a betrayal trauma? What is betrayal trauma theory? Freyd Dynamics Lab. http://pages.uoregon.edu/dynamic/jjf/defineBT.html

Freyd, J. J., & Birrell, P. (2013). Blind to betrayal: Why we fool ourselves we aren’t being fooled. John Wiley & Sons.

Gordon, S. (2020, April 02). How bullying can lead to ptsd in kids. Very Well Family. https://www.verywellfamily.com/bullying-can-lead-to-ptsd-460614

Gušić, S., Cardeña, E., Bengtsson, H., & Søndergaard, H.P. (2016). Types of trauma in adolescence and their relation to dissociation: A mixed methods study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(5), 568–576. http://dx.doi.org/doi/10.1037/tra0000099

Herman, J. L. (1997). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence-from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Idsoe, T., Dyregrov, A., & Idsoe, C. E. (2012). Bullying and ptsd symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 901-911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9620-0

McDonald, M. K., Borntrager, C. F., & Rostad, W. (2014). Measuring trauma: Considerations for assessing complex and non-ptsd criterion a childhood trauma. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(2), 184-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.867577

Ossa, F. C., Pietrowsky, R., Berin, R., & Kaess, M. (2019). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among targets of school bullying. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(43). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0304-1

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). Developmental trauma: The hidden epidemic. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.