In Search of the Successful Psychopath

What is a successful psychopath?

To study a successful psychopath, we must identify what it is to succeed as a psychopath. In a sense, the psychopath that behaves in whatever way they choose and is never caught has succeeded. That behavior may be the classic serial killer but, recognizing that psychopaths may not always be set apart from society, it may also be embezzlement, fraud, identity theft, or just being a nasty coworker. But the goal of studying the successful psychopath is to explore the phenomenon of psychopaths who succeed within the boundaries of normative culture, not those whose transgressions go unnoticed. Further, as Welsh and Lenzenweger observed, defining the successful psychopath as the one who is never apprehended fails to consider the perspective of the individual in question, defining them by their relationship to criminal justice rather than their own experience (2021). What about classic metrics of success in a capitalist society – income, acclaim, and power?

Moving past psychopathy as a monolith

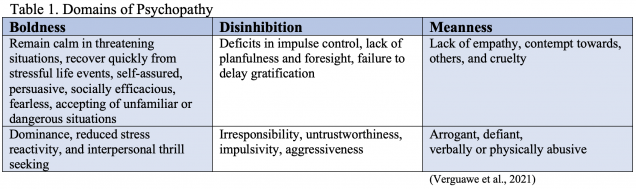

While scores to such as PCL-R can be used to determine the presence and degree of psychopathy – useful for formulating an approach to treatment – the individual components of those scores may become lost once the label is applied. But to facilitate the exploration of an anomaly such as the successful psychopath, researchers have adopted the triarchic approach, allowing characterization of in terms of boldness, meanness, and disinhibition (Table 1) rather than only a total score. In particular, the domain of “boldness” has been hypothesized to be a fulcrum around which the successful psychopath may pivot from the Hollywood serial killer to the hero of the boardroom.

Bold Belgian bosses

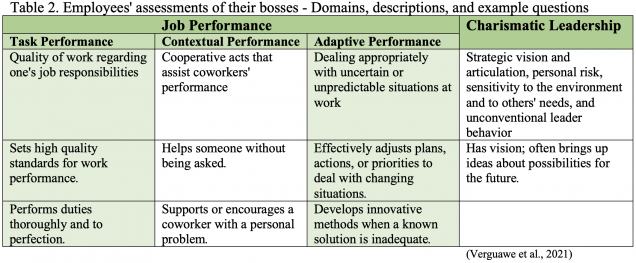

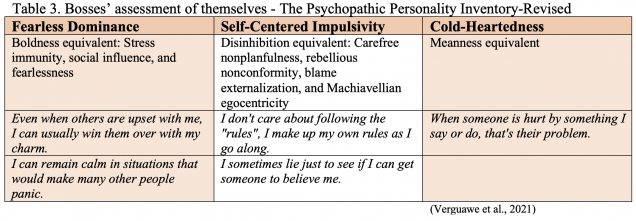

Vergauwe, Hofmans, Wille, Decuyper, and De Fruyt recruited psychology students to evaluate their bosses’ effectiveness as leaders (Table 2), and recruited those bosses to complete the Dutch version of the psychopath exam: The Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised (Table 3). This study was performed twice, to assess for reproducibility, the second with a much larger sample size.

Vergauwe et al. offered three hypotheses. The Differential Severity model suggested a curvilinear relationship between psychopathic characteristics and business success. Psychopathy would increase success until a point of diminishing returns, at which point higher scores would lead to worse performance. This hypothesis did not examine the relationship between specific domains of psychopathy, rather it interpreted the total score. The results from the first and second studies refuted this, showing a linear relationship rather than curvilinear.

The Moderated Expression model added an additional criterion: Conscientiousness, as measured by the self-reported Dutch NEO Five-Factor Inventory (eg. I have a clear set of goals and work toward then in an orderly fashion). It posited that characteristics of psychopaths that might otherwise be maladaptive could be tempered and even made beneficial in the presence of certain qualities (others are noted below). This theory bore fruit in Study #1, showing that Task Performance worsened in individuals with low Conscientiousness as Self-Centered Impulsivity increased. In the presence of high Conscientiousness, Task Performance improved as Self-Centered Impulsivity went up. However, Study #2 did not replicate this result, and the presence of Conscientiousness actually correlated with a steeper drop in Contextual Performance and Charismatic Leadership as Cold-Heartedness increased. Of note, other research has suggested that qualities such as Executive Functioning, Intelligence, or even good parenting techniques may provide the moderating effects that turn increasing psychopathic domain scores into success (Welsh & Lezenwegere, 2021).

It was the Differential Configuration model that provided Vergauwe et al. with the most reproducible results. This hypothesis proposed that increases in certain domains of psychopathy would lead to greater success while increases in others would lead to worsening dysfunction. This was the hypothesis that assumed the least covariance between domains – an increase in boldness need not be accompanied by an increase in disinhibition or meanness, and a lower score in one might not portend lower scores in another. In Differential Configuration, Boldness (Fearless Dominance, in the Dutch model) showed positive, linear relationships with effectiveness, statistically significant in the arenas of Adaptive Performance and Charismatic Leadership. In contrast, Disinhibition was significantly associated with decreasing Task Performance, and Meanness was negatively associated with all leadership qualities. It seems Boldness may be the difference between the successful and unsuccessful psychopath, at least in the business world.

Successful psychopath in the streets – and in the sheets?

Boldness may have cemented its value in the work of Pilch, Lipka, and Gnielczyk when they looked at the role of psychopathic traits and social status as they related to romantic and sexual relationships (2021). In contrast to the other studies, their work left the evaluation of psychopathic characteristics to another individual, not the one being assessed for psychopathy. In further contrast, the research focused on women, a largely neglected population in the world of psychopathy research. The individuals in question were still men, and the study was limited by a heteronormative structure, but it provided women the opportunity to assess their partners’ psychopathic qualities, which were then analyzed in terms of self-reported satisfaction with both romantic and sexual relationships. Boldness won the day once more, identified as the quality most likely to increase women’s satisfaction rather than damage it. Increasing Meanness and Disinhibition scores had a deleterious effect.

What makes a successful psychopath is not yet well-characterized. Even the definition of a successful psychopath is unclear. But research to this point has suggested that Boldness, associated with resilience and social efficacy, may be the key to what makes one psychopath a secretive, perhaps murderous societal aberration, and another the leader of a Fortune 500 company – or perhaps the president of the United States.

Pilch, I., Lipka, J., & Gnielczyk, J. (2022). When your beloved is a psychopath. Psychopathic traits and social status of men and women’s relationship and sexual satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111175

Vergauwe, J., Hofmans, J., Wille, B., Decuyper, M., & de Fruyt, F. (2021). Psychopathy and leadership effectiveness: Conceptualizing and testing three models of successful psychopathy. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101536

Welsh, E. C. O., & Lenzenweger, M. F. (2021). Psychopathy, charisma, and success: A moderation modeling approach to successful psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 95, 104146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104146

One comment

Hi James!

Thank you for developing the concept of a successful psychopath.

It is interesting how you started your discussion from identifying the classic metrics of success. Frankly, power seems to be one of those indicators that corresponds with manipulation. Manipulation is a typical trait of a psychopath that shows how an individual is egocentric while following his self-interests. And indeed this describes how successful people behave.

Truly insightful!

Comments are closed.