Advocating For The Visual Arts In Prison

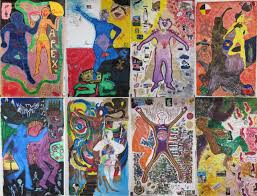

(Boumedda, 2018)

I remember walking by a particular kiosk in the Cancun airport last spring while waiting for a flight back to the U.S. and thinking, “how could something so beautiful be created in such a horrible and traumatic place?” I learned that this was one of 11 boutiques across Mexico called Prison Art, an art training foundation established in 2012 by Jorge Cueto, a formerly incarcerated artist who found healing through creative expression. Jorge’s goal was to create a training program for incarcerated individuals that offered skills necessary for jobs in the fashion industry and visual arts upon reentry, and to promote their work (Cueto, 2020). He also works to teach and employ both incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals in the foundation, which focuses on custom-designed leather products, to assist with rehabilitation while incarcerated, and reintegration into their communities.

This was my first, first-hand experience with prison art, a recreational, therapeutic, and rehabilitative activity with a rich history and base of empirical literature. The earliest known organized form of an art-based activity while imprisoned (albeit it was theater) was that of Cervantes in the 1600’s, and the first documented arts program in American corrections was in the Elmira Reformatory in New York in 1870 (Gardner et al., 2014). The state of California has always been at the forefront of advocating for art programs in prisons; as early as in the 1940’s in San Quentin State Prison individuals were given the opportunity. In 1977, the first federally-funded program, known as Project Culture by the American Correctional Association, was created to provide adults in state prisons with higher-quality activities and opportunities for growth, hoping to reduce behavioral disturbances at facilities (Colorado College, 2016). Large-scale art programs sponsored and administered by facilities themselves are a more recent development in corrections (Gardner, 2014).

Why should we promote exposure to the visual arts in prisons and carceral settings?

The American criminal justice system is based on a punitive, rather than rehabilitative view of human behavior, resulting in over 2 million people behind bars. Each year, more than 600,000 people are released from state and federal prisons, and more than two-thirds are rearrested within 3 years of their release (ASPE, 2019). That is a significant number of individuals returning to families, communities, and society who need to reintegrate, often with significant barriers in securing housing and employment. As a way to provide cognitive, emotional, and practical skills, improve quality of life, and reduce recidivism, among other benefits, providing visual arts activities can be viewed as a form of tertiary prevention or treatment in carceral settings (Bartol & Bartol, 2016, p. 166). Activities such as painting, drawing, ceramics, sculpture, design, and printmaking, among others, constitute visual arts. Although art is frequently not viewed as a necessity or a priority compared to more traditional forms of education or therapy, I would argue that the benefits are clear and worthy of resource allocation.

Photo from New York Times, 2019

Photo from New York Times, 2019

Prison art as a recreational, therapeutic, and rehabilitative activity.

Carceral settings can be traumatizing, re-traumatizing, and intensify preexisting mental health conditions, a setting in which serious mental illness and experiences with trauma are highly prevalent. Art therapy is a structured program typically directed by a particular person with skill in an artistic medium, and is trained to address certain psychological needs of participants (Colorado College, 2016). While this is not the only method of delivery for prison art, art therapy, particularly that which addresses trauma, grief, transition, etc. in those in prison is viewed as the most therapeutic. Art can also be recreational and rehabilitative, where individuals are freely creating in leisure time without necessary supervised direction (Gussak, 2007).

Dr. David Gussak, Ph.D., Professor and Chairman of the Florida State University Department of Art Education is a leading researcher in the field of forensic art therapy. He conducted various studies in prisons measuring the effectiveness of art therapy in decreasing depressive and other symptomatology. (Gussak, 2007). One study found that after 8 sessions of art therapy in a prison, participants had significantly decreased depression, improved overall mood, regulated sleeping patterns, and socialized more with peers. Participants were also more compliant with staff and facility rules and taking medications (Gussak, 2007).

Professor Larry Brewster is an expert in public policy, administration, and management, and he studied and evaluated the California Arts-in-Corrections program for 30 years. His 2014 study of the 12-week arts program in 5 state prisons revealed a reduction in disciplinary reports, greater participation in academic and vocational programs, and increased self-confidence, emotional control, time management, and social competence (Brewster, 2014).

Summary of benefits from empirical studies and national prison art programs.

- Increases and improves:

- Overall mood and wellbeing

- Locus of control and emotional stability From Blogspot by Scott Taylor

- Socialization and competence

- Problem solving

- Time management

- Self-discipline and self-examination

- Creativity

- Self-satisfaction, self esteem, and confidence

- Collaboration

- Accountability

- Hope

- Status, respect, and friendship

- Technical skills that can be applied to a career

- Helps to establish or reestablish identity above that of an incarcerated person

- Promotes non-verbal communication

- Disclosing feelings in a prison environment can be dangerous and/or threatening

- Reduces recidivism and enables successful reentry

- Decreases the number of disciplinary reports

- Form of self-care in a traumatic environment

- Yields feelings of accomplishment and success

- Instill confidence and motivation in pursuing other activities including academics

- Reaffirms that humans are capable of change, empathy, and improvement

- Enhances ability to use leisure time constructively

- Uniquely able to reach inner feelings as an opportunity for reflection

- Provides an “escape” from prison life

- Permits self expression in a prosocial manner

- Decreases symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD

How can we improve access to visual arts for those in carceral settings? It seems as though the benefits may certainly outweigh the costs.

References:

ASPE, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2019). “Incarceration and Reentry.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed April 18, 2020 at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/incarceration-reentry

Bartol, C.R., & Bartol, A.M. (2016). Criminal Behavior: A Psychological Approach (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Boumedda, S. (October 2, 2018). “Empowering Indigenous Women In Prison.” The Link. Accessed April 18, 2020 at: https://thelinknewspaper.ca/article/empowering-indigenous-women-in-prison

Brewster, L. (2014). The impact of prison arts programs on inmate attitudes and behavior: A quantitative evaluation. Justice Policy Journal, 11(2), 1-28.

Colorado College History Department. (2016). “Past, Present, Prison- Art Therapy.” Colorado College. Accessed April 18, 2020 at: https://sites.coloradocollege.edu/hip/art-therapy/

Cueto, J. (February 25, 2020). “The Prison Art Project- About Us.” Prison Art. Accessed April 18, 2020 at: https://www.prisonart.com.mx/about-us/

Gardner, A., Hager, L., & Hillman, G. (May, 2014). “Prison Arts Resource Project: An Annotated Bibliography.” Arts.gov. Accessed April 18, 2020 at: https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Research-Art-Works-Oregon-rev.pdf

Gussak, D. (2007). The effectiveness of art therapy in reducing depression in prison populations. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 51(4), 444-460. Doi: 10.1177/0306624X06294137

Sobek, J. (March 3, 2020). “Beginnings.” The Justice Arts Coalition. Accessed April 18, 2020 at: https://thejusticeartscoalition.org/blog-2/page/2/