Meghan Townes

Meghan Townes is a PhD candidate in the American & New England Studies Program at Boston University. Her dissertation, “Kindred Arts: Art, Authority, and Visions of the Future in Reconstruction and New South Richmond,” looks at how residents of Richmond, Virginia, used the creation and display of art to understand and shape their communities between the end of the Civil War and World War I. A fifth-generation Alabamian, she has a love/hate relationship with her home state.

The Band Goes to Washington:

Re-telling a Family Story About Gender, Labor, and Kennedy’s Inauguration

Every summer, my parents would load me, my sister, two cats, and an assortment of suitcases, snacks, and books into a van and drive south from the D.C. suburbs, down the Great Appalachian Valley through Virginia and Tennessee to north-central Alabama. At Birmingham, we would head west on US 78 and leave the city’s rusting ironworks and sparse skyscrapers behind for the small hamlets, scrubby woodland, and strip-mined hillsides of Walker County. The van would skirt by Jasper, the county seat, and then continue for another twenty minutes until we were driving through Carbon Hill, a line of low brick buildings to our right and the railroad tracks to our left. This was how I first knew Carbon Hill – as the sleepy town we passed through on the way to the family farm and as the place we sometimes went to pick up prescriptions and eat mini hamburgers at a café facing the railroad. The only other thing I knew about Carbon Hill was that, in an inversion of my own yearly journey, its high school band had once traveled to Washington, D.C., to play at the January 1961 inauguration of President John F. Kennedy.

To explain what Walker County means to many Alabamians, a brief story: I once ran into a Birmingham native at a concert in North Carolina. “My mother’s from Walker County,” I said. “Oh, I wouldn’t tell people that,” he replied. During the mid-twentieth century, perhaps even more so than today, Walker County served as a byword for poverty and backwardness in Alabama. In 1950, the Chicago-based Daily Worker, a paper backed by the Communist Party USA, sent reporter Eugene Feldman to Jasper to report on the plight of unemployed coal miners. He wrote, “There are no jobs in Walker County, little to eat, and children are being cheated out of a gay and happy childhood.”[1] Carbon Hill itself had survived miners’ strikes, coal industry contractions, and the Great Depression, but by the time of Kennedy’s election, the town of 2,000 was truly struggling. When the Carbon Hill High School band director suggested his teenage musicians bring $10 spending money for the Washington trip, he was careful to add, “If you can’t afford this much, please see me as soon as possible in my office.”[2] Yet in press releases submitted before the parade by the president of the Band Boosters Club, Carbon Hill’s struggles were transformed: “This band truly represents the spirit and pride of a community that has suffered serious economic setbacks due to the closing of its main source of revenue, the coal mines. Carbon Hill’s optimism about their future is exceeded only by their pride in their band, in being invited to participate in the pageantry of the world’s greatest ceremonial, the Inauguration of the President of the United States.”[3]

The boosters’ president, the one painting the picture of how a resilient community sent its band to Washington, was my grandmother, Valeria Wyers. Valeria was rarely identified by her chosen name, which I seek to rectify in this essay.[4] A sometime journalist who later worked in the Jasper office of Congressman Carl Elliott, Valeria had two children in the band at the time of the inauguration, my Aunt Pat and Uncle Richard. The story of the Carbon Hill High School (CHHS) band’s journey was, therefore, one I knew from an early age. The family narrative goes something like this: Your grandmother worked for Carl Elliott, and Congressman Elliott was a good friend to Kennedy. They [it was never clear which they] raised the money to send the kids up there. It was true that Carl Elliott, who represented Alabama’s 7th District, had campaigned tirelessly for Kennedy in the 1960 election season. Elliott would later write, “When I let President Kennedy know that these boys and girls from Carbon Hill were largely the sons and daughters of coal miners, and that it was the votes of those miners and their wives that had helped him over the hump down here, his people made sure that the band from little Carbon Hill High School was at the front of the line that cold January afternoon, marching in the name of the state of Alabama.”[5]

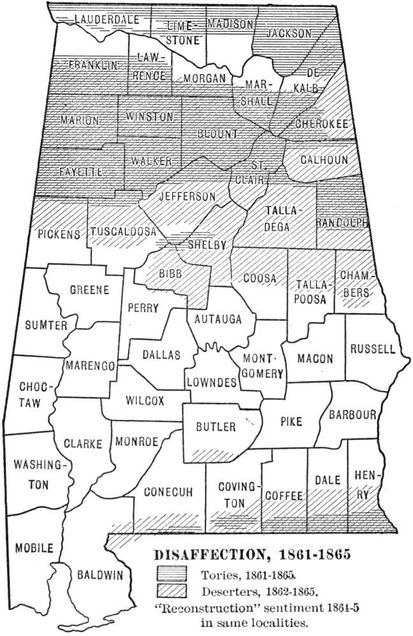

The feel-good story of the coal miners’ children who marched proudly in freezing temperatures for Kennedy appeared not only in Elliott’s 1992 memoir, The Cost of Courage, but in a documentary about Elliott, Conscience of a Congressman, produced by the University of Alabama the following year.[6] It regularly resurfaces in articles published by Jasper’s Daily Mountain Eagle newspaper, in displays at the Carbon Hill City Library, and on community Facebook pages like Carbon Hill Memories. And, in some ways, it is a feel-good story about an underdog band from an underdog town that got to represent the state on the national stage. But this was Alabama in 1960 – no place for a fairytale . Photographs from the parade show the sousaphone bell covers decorated with the battle flag of the Confederacy [Fig. 1].

The all-white band played “Dixie” (Carbon Hill city schools would not integrate until 1965).[7] John Patterson, the governor my grandmother sent letter after letter to, the one she is pictured standing next to in some photographs, won his office in 1958 with the support of the Ku Klux Klan. The year after the Kennedy inauguration, Walker County cast most of its gubernatorial ballots for the hardline segregationist George Wallace.[8] And yet Wallace’s Alabama and the Alabama represented by the CHHS band diverge in unexpected ways.

My grandmother died when I was 7, but she left behind a red-bound scrapbook documenting the band’s journey to the inaugural parade and her own efforts over the fall of 1960 to secure its participation. Growing up, I would leaf through this scrapbook, with its assortment of newspaper articles, correspondence, photographs, and ephemera, and try to match pictures and signatures with the old campaign buttons I kept in my treasures box. Only in returning to the scrapbook as a historian of the American South, as someone who looks at the intersection of image creation and political power, have I begun to tease out the knotty, unruly threads of the narrative I grew up with. While there may well have been a sense that the incoming Kennedy administration “owed” Carl Elliott for his support, the scrapbook shows that the band’s selection was not quite so straightforward. For one thing, Carbon Hill’s mining past – its history of strikes and skirmishes – had long given the town a bad reputation. For another, the band itself was not well-known, certainly not in comparison with ensembles from more prosperous towns that performed across the state and competed nationally. Carbon Hill, in essence, was too noisy in some ways and not enough in others. And, even if the state inaugural arrangements committee did select Carbon Hill as Alabama’s one band for the inauguration, the town would need to raise at least $5000 to cover the cost of transportation and other expenses.[9]

That the CHHS band ended up marching down Pennsylvania Avenue with “lots of flash and lots of noise” (as one press release put it) was a testament to the audacity both of Walker County and of my grandmother .[10] The Daily Worker’s Feldman, despite the poverty he saw in Jasper, observed that “strangely, there is hope here. The people know how to get things done because this is where they built some of the first and strongest unions in the state.”[11] The tumultuous labor history that had given Walker County its “unfavorable publicity,” as a local columnist put it, had also trained its residents in how to organize.[12] Valeria might have spoken politely and dressed neatly, but her actions were a series of small rebellions. She pestered judges, congressmen, senators, and the governor alike to support the inauguration bid. “At first, all she received was discouraging news, but she wasn’t interested in a ‘no’ answer. She wanted an invitation!” the Mountain Eagle reported. In getting the band to Washington, she also moved herself beyond what was considered an acceptable role for a married mother of six, particularly from a small, conservative community.

This paper is an exploration of a story I thought I knew and an assessment of what it teaches me about my identity as an Alabamian, a historian, and a granddaughter. I take the tools of my scholarship and apply them to the fabric of my family history, with sometimes surprising results. What Valeria documented in her scrapbook is not a straightforward narrative about a high school band going to Washington. It is a complicated, even disruptive, one about longstanding intrastate sectional tension, the mostly forgotten legacy of Alabama’s labor organizing, a changing midcentury political climate, and the gendered boundaries of ambition.

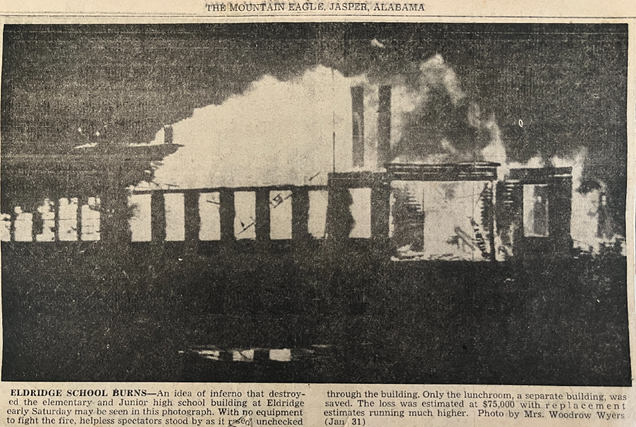

To understand most things in Alabama, you need to go back to the Civil War. From the earliest white settlement in the state, a separation had existed between the hill country in the north, where small farms and settlements predominated, and the lowlands along the Alabama River, where plantation agriculture flourished.[13] The upcountry counties, including Walker, were the least supportive of the state’s secession from the Union in 1861, soon earning them the derogatory nickname of “Tories,” after the American Revolution’s reviled British Loyalists. A map in historian Walter L. Fleming’s 1905 book, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama, marks pockets of Unionist “Tories” and Confederate deserters with horizontal and diagonal lines mark; Walker is covered by both [Fig. 2].

For generations to come, the term “Tories” would communicate a particular type of character to Alabamians. In Fleming’s words, “the Alabama tory [sic] was, as a rule, of the lowest class of the population…There was a certain social antipathy felt by them toward the lowland and valley people…To-day those people are represented by the makers of ‘moonshine’ whiskey and those who shoot revenue officers.” [14] Still, this history of refusal and noncompliance was evidence of a higher moral orientation for some north Alabamians. Among the books that crowded the shelves of my grandparents’ living room was a copy of Wesley S. Thompson’s 1953 novel, Tories of the Hills, a work whose main character is a righteous Winston County Unionist leader.

Carbon Hill was established in 1886 when the growing nearby city of Birmingham, with its blast furnaces and steelworks, made Walker’s coal field profitable. By the early 1900s, a line of mines stretched through the town, clustered on both sides of the railroad leading to Birmingham [Fig. 3].[16]

Carbon Hill might have owed its existence to coal, but from the beginning, it was a tumultuous relationship. A boomtown atmosphere – noisy and undisciplined – persisted for many years, with the sound of gunfire, explosions, rock falls, and labor disputes interrupting the constant productive rumble of mines and trains. In December 1889, 250 miners went on strike from the nearby Kansas City mines, returning to work a month later. The next year, the miners in Carbon Hill went out along with those from other operations in the region.[17] Although similarly short-lived, this second strike led to an eruption of violence in Carbon Hill. Disgruntled white strikers shot into a company-owned house where Black miners were staying, killing one man. Fearing more unrest, the county sheriff wrote to the governor and requested military aid, but the state troops found on arrival that the “armed mob” consisted primarily of rumors. They quickly departed, and the “Siege of Carbon Hill” became something of a state joke. Yet the press reports created an image of Walker County that would linger for decades to come: “It is rough and broken in topography, and the population is sparse and inaccessible, all being conditions that have contributed to an inability to enforce the civil law.”[18]

The mines made Carbon Hill, but as the twentieth century progressed, they would nearly unmake it as well. By the 1920s, the town had settled down to become “a city of beautifully kept homes, fine public buildings…and a large modern well-equipped school building.”[19] Then, beginning in 1929, the Great Depression devastated the industries in Birmingham and the coal mines supplying them. Around Carbon Hill, shafts shut down or reduced their working hours. The situation was so dire that newspapers celebrated when the Moss-McCormick Mine returned to a three-day-a-week operation because “the payroll means a great deal to Carbon Hill.”[20] The county’s budget also suffered, with coal operators paying lowered taxes on their struggling properties.[21] Those miners still at work found themselves often at odds with the coal companies over working conditions and collective bargaining. Unions in Walker, Jefferson, and Bibb Counties called for a strike in March 1934 that eventually included some 10,000 miners and 40 coal mines.[22] As the decade progressed, the coal industry’s turbulence and the impact of low agricultural prices on the area’s small farms put increasing strain on Carbon Hill’s economy.

Help came in the unlikely form of two federal agencies, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Public Works Administration (PWA). Under the WPA and PWA, Carbon Hill received an updated sewer system and wastewater treatment plant, a swimming pool, municipal garage, jailhouse, and a handsome new high school made of brick.[23] These projects not only improved the infrastructure and appearance of the town but provided much-needed work for unemployed residents of the town and surrounding areas. The new school opened with a formal dedication ceremony on September 7, 1936. Students entering its doors a week later were not beginning new grades, however. When the state legislature had failed to provide enough funding that spring, schools across Walker County closed, leaving students to finish their work in the fall.[24] Like the decades of labor organizing at Carbon Hill’s mines, the federal intervention and the failure of the government down in Montgomery created the backdrop against which the CHHS band’s inauguration campaign took place. The people of Walker County had learned that to be listened to, you sometimes needed to circumvent the normal flows of power from local to state to federal.

In late April 1940, a census enumerator made his way through the small hamlet of Eldridge, six miles from Carbon Hill. Among the households he recorded was that of 27-year-old Woodrow Wyers. During the 1940s and 1950s, Woodrow worked as a surveyor and timber foreman for the mines. At the time of the census, like four other men listed on sheet 10B, his employer was the WPA. Keeping house and looking after their two-year-old son was Woodrow’s young wife, Valeria. The enumerator noted her highest level of education as the third year of high school; had she graduated, my grandmother would have been a member of the Carbon Hill High School class of 1937. Instead, she married between the closure of schools in the spring of 1936 and their reopening in September and never returned.[25] That my grandmother did not finish high school was neither a family secret nor a source of shame. Still, it is hard to look at a family photograph from the late 1940s in which she gleefully wears her sister Oveta’s cap and gown and not sense an underlying regret [Fig. 4].

The sense that things should have been different drove her to continue her education independently by reading widely and taking part in debates and discussions at local women’s clubs. If anything, the experience made her more, rather than less, willing to make herself heard beyond the walls of her home.

Valeria threw herself into education advocacy as her children aged, becoming president first of the Eldridge Junior High School Parent Teacher Association and then of the Walker County PTA Council. In her county role, she traveled to conferences and board meetings across the state and began to make connections that she would harness for the band’s benefit. By the late 1940s, my grandmother was also serving as an Eldridge correspondent for Jasper’s Mountain Eagle, using her columns to slip in news about school events and solicit members for the PTA. On occasion, her reporting diverged from the usual updates on birthday parties and hospitalizations. After a local house burned in 1947, she gathered information about how the fire started – faulty wiring in the ceiling – and detailed the loss of the family’s carefully canned and dried food stores.[26] Another time, she crouched on the bank of a local creek and snapped a photo of the police recovering a body – an incident that did not make it into her social column.

Valeria and her Kodak Brownie were present when Eldridge’s conjoined elementary and junior high school building burned on January 31, 1952. In a photograph published on the front page of The Mountain Eagle, she captured the skeleton of the wooden building outlined starkly against the roiling white-hot flames [Fig. 5].

Ten months later, students were still attending classes in an old orphanage dormitory nearby. A nationwide steel strike in the spring and summer had curtailed production, and a small school in Walker County was not a priority once supplies became available. The steel was promised for the summer, then promised for the fall, and still failed to arrive. At some point, my grandmother reached out to Carl Elliott, the congressman representing Walker County. On November 24, he sent a telegram informing her that steel had been allocated and would arrive within twenty days. “County supt office assures me that it is its intentions to proceed with construction in all due haste,” he dictated.[27]

A tenant farmer’s son originally from Franklin County, Carl Elliott had practiced law and served as a judge in Jasper before his election to Congress in 1948. Like my grandparents, Elliott was a New Deal liberal, a believer in labor, economic reform, and the benefits of federal money and federal projects [Fig. 6].[28]

In particular, he saw education as critical to lifting Alabamians out of poverty; during his time in Congress, he helped pass the Library Services and Construction Act of 1956 and the National Defense Education Act of 1958. By the mid-1950s Walker County needed all the help it could get. The county’s coal mines had seen a resurgence during World War II, but now almost all had closed. In September 1954, Elliott and Alabama’s senators, Joseph Lister Hill and John Sparkman, advocated for Alabama’s inclusion in the federal government’s coal purchase program, with Elliott specifically asking for the government to buy coal from Walker to relieve the county’s unemployment.[29]

However, Elliott’s concern and advocacy remained focused on white residents. Like Senators Sparkman and Hill, he signed the Southern Manifesto opposing racial integration in 1956 and later voted against the Civil Rights Acts. Even as late as the 1950s, it was possible for an Alabama politician like Elliott to consider themselves progressive, liberal, and segregationist. Charles K. Roberts, in analyzing the state’s “mixed political legacy” suggests that Alabama “had perhaps the strongest tradition of economic liberalism of any southern state before the civil rights movement.”[30] But as the 1960s began, Elliott’s support for federal programs, from Truman’s Fair Deal to Johnson’s Great Society, and his commitment to the national Democratic Party would put him at odds with a changing political landscape at home.

In the late summer of 1960, the idea that the CHHS band would be marching in the inaugural parade of John F. Kennedy seemed inconceivable to nearly everyone – except my grandmother. “Mrs. Wyers decided Sept. 2, two months before the election, to see if an invitation could be secured. She first contacted Rep. Carl Elliott who began work on an invitation,” one article reported.[31] I wish I knew what happened on September 2. My grandmother was, as another article would note, “an ardent Kennedy-Johnson supporter,” but in early September, there was no guarantee that the Democratic ticket would win. None of the televised debates had occurred, and Kennedy had not even made his visit to neighboring Georgia (he would not come to Alabama).[32] Maybe Valeria never doubted that Kennedy – just a year older than her, charismatic, idealistic –would become the next president. Or maybe she figured that either way, the inauguration was the inauguration and that what Carbon Hill needed was an opportunity to reshape its identity in the most visible (and audible) way possible.

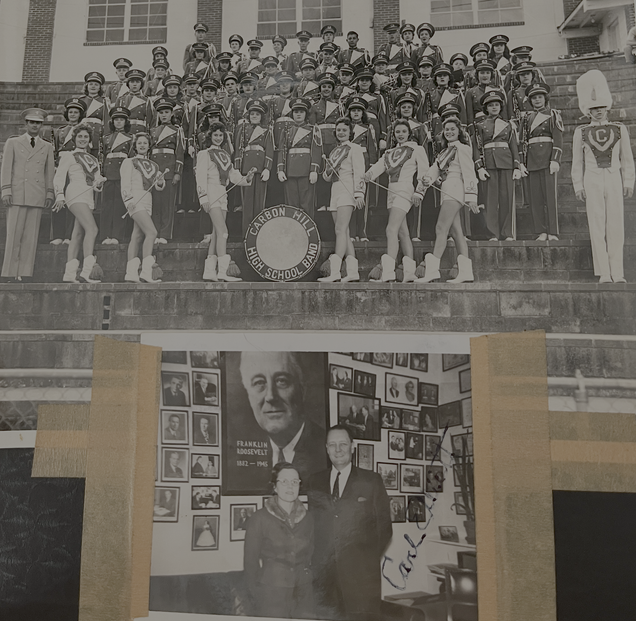

In some ways, it was a particularly audacious ambition. The CHHS band did not have a long history, having been founded in 1940 and reorganized in 1955. While it participated in Governor John Patterson’s inaugural parade in January 1959, the band had never taken part in state or local performance competitions. Between the gubernatorial inauguration and the presidential one, the band also had to contend with a change in style and leadership. The new director, twenty-four-year-old William Driskell, brought with him the “Emma Sansom formula,” named after the nationally-titled band at his former high school in Gadsden. This approach was designed to create crowd appeal, with a repertoire that emphasized drums and trumpets and dynamic step patterns. Performing with “lots of flash and lots of noise,” required not just hours of practice by the young musicians but the instruments and uniforms to match – an expensive proposition.[33]

The CHHS Band Boosters Club formed in September 1959 to support the band’s reinvention.[34] My grandmother was elected the first president and, from the start, appeared to consider her (and the club’s) remit broadly. The Boosters organized bake sales and hawked candy, as expected, but also booked paid appearances for the band at political rallies. These appearances were strategically bipartisan. In the runup to the 1960 elections, CHHS performed at a Republican meeting in Jasper, the “Big Democrat Rally” in Carbon Hill, and a GOP parade and rally in Fayette (earning $100 there alone). Valeria was a constant publicist for the band, submitting updates with enticing snippets to the Mountain Eagle, which sometimes required an awkward use of the third person. “Mrs. Woodrow Wyers announces that many interesting speakers will be there,” she wrote in one column.[35]

As the band began its pursuit of an inauguration slot, Carl Elliott spent his fall stumping for Kennedy. Kennedy was not an easy sell for many white Alabamians, who disliked his Catholicism and his support for the civil rights movement. Only five of Alabama’s eleven Democratic electors had committed to Kennedy, and, in November, the six unpledged electors would cast votes for non-candidate Harry F. Byrd, the arch-segregationist senator from Virginia.[36] Elliott made more than 250 speeches on Kennedy’s behalf, putting his full political capital behind the candidate. The Birmingham News’s Washington correspondent, James Free, was one of the earliest to connect CHHS’s success to Elliott’s dogged electioneering. “The Democrats in U. S. Rep. Carl Elliott’s district,” he wrote, “worked harder in the campaign than any other district of the state. They held 300 political meetings, over-subscribed their quota, and turned in $14,000 for the Democratic campaign.”[37] Between the election and the selection of marching units for the inaugural parade, however, an entirely separate campaign took place.

Three days after meeting Senator John Sparkman at a fundraising “Koffee for Kennedy” in Jasper, my grandmother wrote him a letter to request an inauguration slot for CHHS. Sparkman’s response was encouraging; next to the typed text, he included a handwritten assurance that he remembered their talk about the band and would do his best. Sparkman chaired the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies and proved a strong ally for the band. Initially, though, even he was uncertain who had the power to select bands for the state. Valeria wrote to Governor John Patterson in mid-November and received a short reply from his chief of staff, Joseph G. Robertson: “Governor Patterson is in receipt of your letter of November 15th and wishes to advise that your request…will be referred to the Inaugural Committee.” Never one to let things stand, she had already begun to request assistance from Walker County connections. Judge Roy Mayhall, chair of the Alabama Democratic Executive Committee, relayed to the governor that “Mrs. Woodrow Wyers, of Eldridge, President of this Club, has asked me to write you to see if there is any way to secure an official invitation, as the Band is most anxious to make the trip.” Robertson sent another polite response (“the request…will be given every consideration”), but by the end of the month, the governor’s office was also responding to inquiries from Sparkman and Elliott.[38]

Sparkman soon discovered that the person with the power to make the band selection was the chairman of the State Democratic Inaugural Committee, Ed Reid. In a letter communicating this to Valeria, he shared that the national parade committee advised against the “use of high school bands due to the hardship incurred in the parade,” citing the four-mile-long route. However, he added, this was only advisory and not binding, and if she wanted to continue, she and Elliott should write immediately to Reid.[39] What transpired next is a little unclear. Reid wrote to Valeria on December 8 that it had been a “pleasure to [do] what I could to land the invitation for you,” but the newspapers were reporting that no decision had been made a week later. Carbon Hill appeared in some reports as one in a list of five bands, including Emma Sansom and the University of Alabama, under consideration. It was not until December 21 that Reid formally announced the members of Alabama’s parade unit, including CHHS.[40]

My grandmother’s scrapbook contains one intriguing article that might explain the confusion. The article, clipped from an unidentified newspaper, states that after offering an inaugural parade band slot to CHHS, Ed Reid and the State Democratic Inaugural Committee also invited the high school band from Auburn, a university town east of Montgomery. Yet the national inaugural committee only allowed each state one band, a restriction communicated as early as December 2.[41] Reid would later tell the press that he and the other state officials had mistakenly believed they could send two bands to the parade. Whenever Alabama’s committee learned of the band limit, they did not immediately accept it. They called their national counterparts to get the policy altered – unready, it seems, to allow Carbon Hill to represent the state alone. No exceptions could be made, so, as Reid told the president of the Auburn Band Parents Association, since CHHS received the first invitation, the band from Walker would go to Washington.[42] Unspoken was the possibility that if Carbon Hill failed to raise the money, a better-known band like Auburn or Emma Sansom could make the trip instead.

Fundraising for the trip began on December 14. As chair of the fund committee, Valeria wrote to the governor the following day to share their progress, detail the anticipated expenses, and request the state’s assistance. She reported that the citizens of Walker had already donated $525 and were expected to add another $1000-1500 in the next week. Although Patterson had recently offered the band a noncommittal “I certainly hope that everything will work out,” he had a check for $2000 cut from the state’s coffers soon after receiving her December 15 letter.[43] The news made the front page of the Mountain Eagle and kicked off a series of articles that tracked the band’s campaign. The newspaper appealed to the paper’s readership for support. Euna Mae Nixon, the society editor, urged the county’s “club women” to send in money so that they could show television viewers from across the country “the products of Walker County.” “It would be heartbreaking,” she wrote, “to think that another band would be asked…because this county couldn’t raise $3,000.”[44]

Valeria neatly recorded donations in pages torn from a spiral-bound notebook, which she later slipped between two scrapbook pages. The 119 names include every kind of civic organization, local government entity, and private enterprise imaginable.[45] Most gifts were for amounts between $5 and $50: $15 from the Flavo Rich Dairy and $11 from the Nauvoo Sock Hop; $5 each from the Frosty Walk-Inn cafe and People’s Drug Company of Jasper; $2.50 from teenager Marian Johnson, collected in nickels and dimes from her neighborhood friends; $50 from Frank Cobb, a retired coal operator who created the “Sponsor a Band Member” club; $1, from a 77-year-old widow named Ella Ann Sides. Carl Elliott donated, as did his predecessor in Congress, Walter W. Bankhead. Roy Mayhall gave in his own name and also spent time soliciting donations. In January, he visited William Mitch and Tom Crawford of the United Mine Workers in Birmingham to see if the union could contribute.[46] The fund committee announced its success on January 16 with an article on the front page of the Mountain Eagle. “When we first started collecting the money, many people said it couldn’t be done,” my grandmother told the paper, “yet the good people from all over the state of Alabama, but mostly from Walker County, have come to our aid.”[47] The CHHS band would be part of a national spectacle, one whose images and sounds would enter the collective memory of the American people, and Valeria wanted the record to show who had put them there.

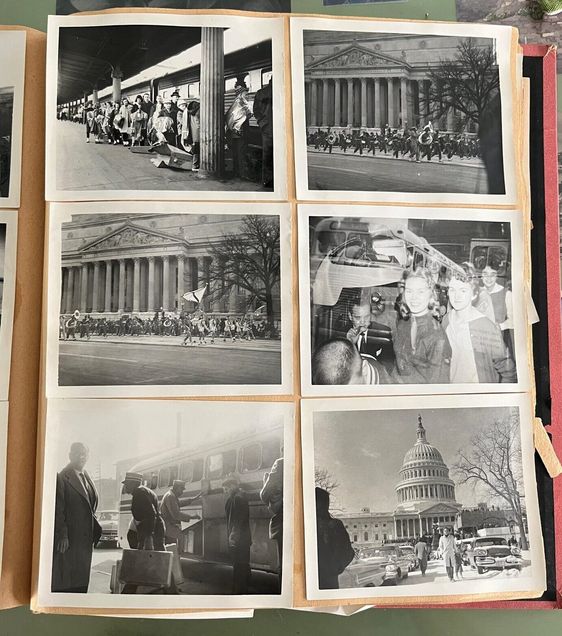

The trip passes in a series of photographs pasted in my grandmother’s scrapbook – the students waiting in line at the station, their pressed uniforms protected by plastic. Then, lounging on the train, my aunt and uncle among them, listening to portable radios (“rock and roll music,” the Birmingham Post-Herald dutifully reported).[48] Eighteen hours later, there they are, arriving in Washington. One image shows my grandmother and Roy Mayhall, searching for their bus in front of Union Station. Finally, the day of the parade itself, the city full of cars and people and covered in more snow than any of them had seen before [Figs. 7-9]. Eight inches of snow fell on the Washington area the night before the inauguration. By the next morning, while the main route had been cleared, the side streets where marching units assembled were full of ice and slush. “I’ve never seen a group of kids get as cold as they did. Those majorettes nearly froze to death,” Carl Elliott would remember.[49]

Despite the weather, the CHHS band made a lasting impression. The band’s bright blue-and-white uniforms, quick-stepping, and selection of lively marches like “Gate City” and “Burst of the Trumpets” entertained spectators along the parade route and television viewers across the nation, who could watch the inauguration in color for the first time. The television newscasts focused at length on Carbon Hill, with the “coal town to nation’s capital” narrative promoted by my grandmother’s press releases making for irresistible “personal, human interest material,” as one researcher from NBC’s Washington bureau put it.[50] The band followed John Patterson’s car down Pennsylvania Avenue, and the governor was constantly, loudly reminded of their presence. When they passed the reviewing stand where Kennedy and other dignitaries watched, they played the jazz standard “Stars Fell on Alabama”[51] – All the world a dream come true / Did it really happen, was I really there, was I really there with you? The band’s assertive performance, and their visual and aural proximity to power, answered the question of whether Carbon Hill could truly represent Alabama. For once, the town from Walker County was making the right kind of noise.

If the parade was the most visible evidence of my grandmother’s successful campaigning, the visit to the U.S. Capitol two days before was the most compelling. At Carl Elliott’s invitation, the band and its chaperones toured the building before entering the House Chamber. Elliott spoke, as did Senator Sparkman, Governor Patterson, and Valeria, who introduced the chaperones. A member of the Jasper Toastmistress Club, my grandmother had worked for many years on how to “speak accurately, with poise,” and her ability to command attention using her voice, despite her gender and unassuming appearance, is evidenced by the way others responded to her.[52] Likely during this event, she shared some “brief ideas regarding active democracy in Alabama,” which Sparkman referenced in a later letter. “We have a great deal to do in order to get it going and keep it going,” he agreed, urging her to return “with time for a good talk.”[53] But the Carbon Hill contingent left Washington at 8 pm the day of the parade, and by Monday the students were back in class.

I wish I could say that my grandmother returned to Washington and talked with Senator Sparkman, shared her ideas widely and encouraged more communities to engage in advocacy so that places like Carbon Hill could not be ignored. She certainly tried. After the band’s return to Carbon Hill, Valeria began to work as an assistant for Carl Elliott from his Jasper office. Having recognized the political power of her voice, she gave speeches to local Walker County organizations during his 1962 re-election campaign.[54] But from 1963 onwards, Elliott, Judge Roy Mayhall, and those who worked for or supported them were caught out by the rise of the “states’ rights” rhetoric and reactionary racial politics driven by the state’s new governor, George Wallace. The New Deal liberals who had believed in labor and the federal government and who had seen Carbon Hill as an example of the possibilities of both were no longer representative of the political majority in the state. Wallace and his followers created a separation between the national and state Democratic parties so severe that someone like Elliott, who served on the influential House Rules Committee during Kennedy’s administration, became the enemy.

After losing his congressional seat in 1964, Elliott ran for governor against Wallace’s wife, Lurleen, two years later.[55] By then, he had taken the “moderate” position that integration would occur but urged the federal government to slow down the process. During his failed campaign, Elliott made a point of condemning the Ku Klux Klan and George Wallace, who he called “the greatest demagogue of all time…a real hater.” In response, his billboards were defaced, his campaign staff harassed, and his rallies threatened by bombs.[56] The shouts of striking miners, the rattle of coal machinery, and the thud of marching musicians that had defined Walker County were now subsumed by a new Alabamian soundscape.

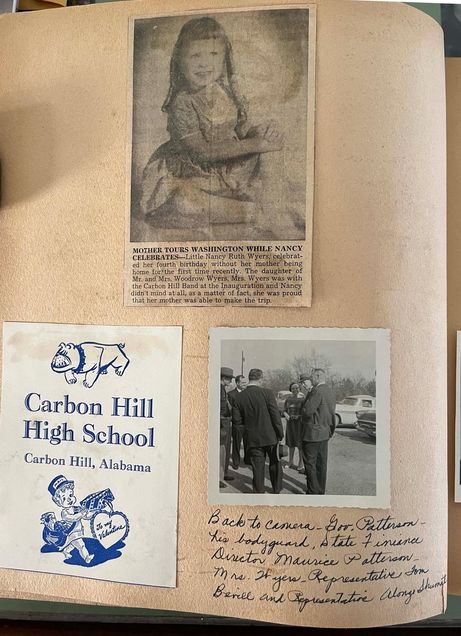

After Elliott’s defeat, my grandmother worked at a bookstore in Jasper and continued her involvement in local politics. A tension existed between her abilities and ambitions and her context, however. Shortly after the band’s return to Carbon Hill, the photographer who accompanied them to Washington wrote in the Mountain Eagle that “if any one person is responsible for the Carbon Hill Band being able to participate in President Kennedy’s inaugural parade…it’s energetic Mrs. Woodrow Wyers.”[57] Then, a week later, the same paper published a photo of my youngest aunt with the cutline, “Mother Tours Washington While Nancy Celebrates” [Fig. 10].[58]

Although the text made it clear that “Little Nancy Ruth Wyers” did not mind Valeria missing her fourth birthday, the implication of neglect was clear. My own mother, a young teenager in the mid-1960s, remembers the casual remarks of “concern” made by neighbors, friends, and even family. Women with children at home did not work elsewhere if they could help it. Even Mary Allen, Carl Elliott’s longtime aide, wrote Valeria that “rearing a fine family…may prove to be your most outstanding contribution.”

I have not been back to Carbon Hill in over twenty years. There is not much left of the town my grandparents knew. The Carbon Hill High School, the one the band left from in January 1961, burned in the summer of 2002. That November, powerful tornadoes tore through downtown, destroying the elementary school and damaging municipal buildings, shops, and residences.[60] An attempt at strip mining, seen in the scarred landscape surrounding the town, could not disguise the fact that the coal seams had been played out by the late twentieth century.[61] Ultimately, these shifts have led to demographic decline; between 2000 and 2020, the town’s population fell from 2,071 to 1,762.[62] Yet sixty years later, members of the Carbon Hill Memories Facebook page still happily share their memories of the Kennedy inauguration – the weather (“freezing”), their excitement, but also the sacrifices that had to be made for the trip (“It took everything my parents, aunts, and uncles could give”). In remembering the inauguration, they also remember Kennedy, who remains beloved (a testament to the lasting impact of Elliott’s campaigning, perhaps). With the success of the Republicans’ Southern strategy, Kennedy’s party has not fared as well. “John Kennedy would not recognize the Democrats now,” one post reads.

In 1990, Carl Elliott was awarded the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award, which recognized both his contributions as a congressman and the political price he paid for opposing George Wallace. The memoir, documentary, and articles that followed have, in some ways, restored his voice and his viewpoint to the public stage. And yet, to be honest, I write this piece not to add to those, not, as a historian traditionally might do, to offer a scholarly intervention or to place the Carbon Hill High School band in conversation with this or that argument. In reading through the carefully preserved letters, newspaper clippings, and photographs in Valeria’s scrapbook, I realized how little I, or anyone else, truly knew about why the band went to Washington. And, by extension, how little I understood of my grandmother’s boldness in defying the expectations placed on her and on her community. As a department representative for the Boston University Graduate Workers Union, I often told people that I had no family connection to unions or organizing. I see now that the type of community building we undertook to create BUGWU is one with which my grandmother and the people of Carbon Hill would have been very familiar. I also see that disruption can take many forms, from the short blast of a trumpet to a hand signing endless letters to a persistent refusal to “take NO for an answer.”

[1] Eugene Feldman, “Deep South is Hit Hard,” Daily Worker, March 26, 1950, reprinted in “Here’s What Daily Worker Says,” Daily Mountain Eagle (Jasper, AL), August 3, 1950, p. 2.

[2] William Driskell, “General Information,” 1961, private collection.

[3] Albert Shaw and Valeria Wyers to NBC News Publicity, January 13, 1961, private collection.

[4] She was born Hester Valeria but went by Valeria, which is the name she passed on to my mother. According to the social conventions of the time, she was almost always referred to as Mrs. Woodrow Wyers – she was named in relationship to someone else. I am careful, therefore, not to solely use “my grandmother,” which works in a similar way.

[5] Carl Elliott, The Cost of Courage (Doubleday, 1992), 196-197.

[6] Elliott, The Cost of Courage; Conscience of a Congressman: The Life and Times of Carl Elliott (University of Alabama, Center for Public Television and Radio, 1993), The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection at the University of Georgia, American Archive of Public Broadcasting, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-526-v40js9jh61.

[7] Marion S. Barry and Betty Garman, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “SNCC: A Special Report on Southern School Desegregation,” 1966, Civil Rights Movement Archive, accessed October 31, 2024, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/65_sncc_school-rpt.pdf.

[8] See “Election Results Archive – Governor, 1946-2010,” Alabama Secretary of State, accessed November 2, 2024, https://www.sos.alabama.gov/alabama-votes/voter/election-data.

[9] John Sparkman to Valeria Wyers, December 2, 1960, private collection.

[10] Albert Shaw and Valeria Wyers to NBC News Publicity, January 13, 1961, private collection.

[11] Feldman, “Deep South is Hit Hard.”

[12] Euna Mae Nixon, “Euna Mae’s Talk of the Town,” The Mountain Eagle, December 29, 1960, p. 5.

[13] It should be acknowledged that the lands now known as Walker County were originally home to the Muscogee Creek people, who were forcibly removed in the early 19th century. Additionally, slavery certainly existed in the county as well. At the time of the Civil War, Walker had 519 enslaved residents out of a population of 7,980, with no free residents of color noted. U.S. Census Bureau, Census of 1860, Classified Population of the States and Territories, By Counties. State of Alabama, Table No. 2 – Population by Color and Condition, page 8.

[14] Along with neighboring Winston and Blount Counties, Walker would also provide the majority of volunteers from Alabama to the Union Army. Howell Raines, Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta – and Then Got Written Out of History (Crown, 2023), xxiii. Walter L. Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (Norwood Press, 1905), 114. Map p. 110. Fleming had been a student of William Archibald Dunning at Columbia and became a leader of the Dunning School, a group of historians who reviled Reconstruction and praised the conservative “redemption” of the South. In Silent Cavalry, Howell Raines examines how such historians obscured and ignored Alabama’s Unionism for much of the twentieth century.

[15] Walter L. Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (Norwood Press, 1905), 114. Map p. 110. Fleming had been a student of William Archibald Dunning at Columbia and became a leader of the Dunning School, a group of historians who reviled Reconstruction and praised the conservative “redemption” of the South. In Silent Cavalry, Howell Raines examines how such historians obscured and ignored Alabama’s Unionism for much of the twentieth century.

[16]John Martin Dombhart, History of Walker County, Its Towns and Its People (Thornton, AR: Cayce Publishing Company, 1937), 83; Ethel Armes, The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama (Cambridge, MA: University Press, 1910), 497-498. Alabama Coal Operators Association, Map Showing Location of Mines in Operation by Alabama Coal Operators 1908, Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection, https://cdm16044.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4017coll7/id/760/rec/1. In 1907 alone, the No. 5 and 6 mines, owned by the Galloway Coal Company, produced an impressive 605,824 tons.

[17] “The Carbon Hill ‘Strike’,” Birmingham (AL) News, December 30, 1889, p. 6; “At an End! Termination of the Great Miners’ Strike,” Birmingham News, January 14, 1891, p. 5. As many as 800 miners went out in this later strike from the mines surrounding Carbon Hill – see “Alabama Items,” Huntsville (AL) Weekly Democrat, January 28, 1891, p. 2.

[18] Newspaper reports of the incident vary widely. However, Black workers, often brought to serve as machine men in place of less reliable locals, were frequently the targets of racial violence. “The Walker War,” Birmingham Post-Herald, February 3, 1891, p. 1. For other (often conflicting) reports on the violence, see “Nine Men Shot at Carbon Hill,” Montgomery Advertiser, February 1, 1891, p. 7; “Call for Troops,” Birmingham News, February 2, 1891, p. 5; “Row at Carbon Hill,” Eufaula (AL) Daily Times, February 3, 1891, p. 1; “The War in Walker,” Birmingham Post-Herald, February 4, 1891, p. 4; and “Trouble At Carbon Hill,” Vernon (AL) Courier, February 5, 1891, p. 1.

[19] “Carbon Hill is Second City in Walker County,” The Mountain Eagle, October 30, 1930, p. 43; “Carbon Hill’s School Rated Among Finest,” The Mountain Eagle, October 30, 1930, p. 43.

[20] “50 Men Given Work at Carbon Hill Mine,” Our Mountain Home (Talladega, AL), May 24, 1933, p. 3; “Moss-McCormick Mines Runs Five Days Weekly,” The Mountain Eagle, November 15, 1933, p. 10.

[21] “Ask Assessment Cuts,” Birmingham News, July 8, 1931, p. 20.

[22] “Miners Back at Work as the Strike Ends,” Centreville (AL) Press, March 22, 1934, p. 1; “Officers of Observation Squadron Praised for Work in Miners Strike,” Birmingham News, March 26, 1934, p. 7. Some sources claim that all of Carbon Hill’s mines closed during the Great Depression, but I have not found evidence of this. See, as a counterpoint, “Walker County Mines Rival 1929 ‘Boom’ Days,” Shelby County (AL) Reporters, November 16, 1939, p. 1, or Bob Kincey, “Labor,” Birmingham News, May 16, 1937, p. 15, which lists local mine unions in Carbon Hill that donated funds to flood relief.

[23] Being federal projects, these projects have an impressive amount of documentation still available. See “Carbon Hill Sites,” Living New Deal, Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley, accessed November 6, 2024, https://livingnewdeal.org/us/al/carbon-hill/ ; “Carbon Hill,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, Alabama Humanities Alliance, accessed November 6, 2024 https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/carbon-hill/ . “Carbon Hill’s $52,000 High School Nears Completion,” The Mountain Eagle, May 21, 1936, p. 3.

[24] Walker County high schools were less disrupted than elementary and junior high schools and stayed in operation until May. In Carbon Hill, which had an independent school system, seniors were allowed to complete their work and graduate in May, but other pupils would continue “in the grade they were in last year until the work is completed.” “Carbon Hill,” The Mountain Eagle, September 3, 1936, p. 2. See also “Many Schools May Be Closed,” The Mountain Eagle, February 27, 1936, p. 1; “Schools Close in Walker Co.,” The Mountain Eagle, March 5, 1936, p. 1.

[25] Woodrow Wyers, 1940 United States federal census, Eldridge, Walker County, Alabama, series T627, roll 0087, page 10B, Ancestry.com.

[26] Valeria Wyers, “Charlie Farris Home is Razed,” The Mountain Eagle, October 9, 1947, p. 6. The loss of the stores not only undid countless hours of work but also, with the approach of winter, threatened food insecurity.

[27] Carl Elliott to Valeria Wyers, telegram, November 24, 1952, private collection.

[28] Both Valeria and her husband, Woodrow, were active in local Democratic circles and had likely crossed paths with Elliott before the school fire, possibly as clients of his law practice. The level of Democratic loyalty in the Wyers family was such that my grandfather – born in June 1912 – did not receive his name until the presidential election in November (thus, Woodrow Wilson Wyers). This is one of the more embarrassing family anecdotes.

[29] “Alabamians Ask U. S. Aid Miners,” The Decatur (AL) Daily, September 26, 1954, p. 10.

[30] Charles K. Roberts, “Race, Wallace, and the ‘9-8’ Plan: The Defeat of Carl Elliott,” Alabama Review 62, no. 2 (2009): 115.

[31] Bill Jones, “Mrs. Woodrow Wyers.”

[32] James Free, “At Inauguration – Carbon Hill Band Marches,” Birmingham News, January 20, 1961. This article is clipped and pasted into my grandmother’s scrapbook but does not match the digitized News issues for the 20th. The digitized copies are likely a different edition.

[33] Albert Shaw and Valeria Wyers to NBC News Publicity, January 13, 1961, private collection. When Driskell ordered sixteen new uniforms in August 1960, the total charge was $1444.23. Kling Bros. & Co. Inc. to William M. Driskell, August 3, 1960, private collection

[34] Its constitution set out its purpose as “to awaken a wide and intelligent interest” in the club, to provide financial, moral, and intellectual assistance to the band, and to “acquire and distribute accurate information” about the club’s progress. The president’s role, defined in the by-laws, merely included presiding over and calling all meetings, appointing committees, and filling any vacancies. “Constitution and By-Laws of Carbon Hill Booster’s Club,” 1959, private collection.

[35] “Vardaman, Dodd Blast Demos in Jasper Meet,” The Mountain Eagle, October 3, 1960, p. 1; Valeria Wyers, “Carbon Hill Band Parades at Auburn,” The Mountain Eagle, October 13, 1960, p. 7; “GOP Rally to be Held Here Sat’day M’ning,” Fayette County (AL) Times, October 27, 1960, p. 1. Valeria handwrote the amount earned in Fayette next to the pasted article in her scrapbook, adding that the band also sold $50 in candy while in town.

[36] Kennedy was credited with all the state’s Democratic electoral votes, giving him the victory over Republican Richard Nixon. Alabamians voted not for candidates but for up to eleven electors, meaning they could split their vote between candidates. Because of the confusion about how to count Alabama’s popular vote, there remains disagreement about whether Kennedy actually won the popular vote nationally. See Brian J. Gaines, “Popular Myths about Popular Vote-Electoral College Splits,” PS: Political Science and Politics 34, no. 1 (2001): 71–75.

[37] Louis D. Silveri, “Leadership for Change: Appalachian Alabama’s Congressman Carl Elliott and Modern America,” Journal of the Appalachian Studies Association 6 (1994): 159; Free, “At Inauguration.”

[38]John Sparkman to Valeria Wyers, November 5, 1960; Roy Mayhall to Valeria Wyers, November 16, 1960; Joseph G. Robertson to Valeria Wyers, November 18, 1960; Roy Mayhall to John Patterson, November 21, 1960; Joseph G. Robertson to Roy Mayhall, November 23, 1960; Carl Elliott to Valeria Wyers, November 30, 1960, all private collection.

[39] John Sparkman to Valeria Wyers, December 2, 1960, private collection.

[40] Ed Reid to Valeria Wyers, December 8, 1960, private collection. This was handwritten, so I find it less likely that a “1” was forgotten in front of the 8 than had the letter been typed. Clarke Stallworth wrote that the band possibilities were “Emma Sansom of Gadsden, Carbon Hill, Auburn, Robert E. Lee of Montgomery, and the University of Alabama.” See “Governor Going to Inauguration,” Birmingham Post-Herald, December 15, 1960, 1. “State to Strut at Inauguration,” Alabama Journal (Montgomery), December 21, 1960, 19.

[41] Bruce G. Sundlun to John Sparkman, December 2, 1960, private collection.

[42] “Mixup Cancels AHS Band Trip,” contained in Valeria Wyers scrapbook, private collection. I have not yet been able to match this article to a publication.

[43] Valeria Wyers to John Patterson, December 15, 1960; John Patterson to Valeria Wyers, December 15, 1960; John Patterson to Valeria Wyers, December 21, 1960, all private collection. The state also sent $2000 to the Mobile County Sheriff’s Posse, which was the other marching unit for the parade. I like to think Patterson was just trying to be equitable.

[44] Euna Mae Nixon, “Euna Mae’s Talk of the Town,” The Mountain Eagle, December 29, 1960, p. 5.

[45] The American Legion Post 101 in Carbon Hill even held a special bingo night, with all proceeds going to the band fund. Euna Mae Nixon, “Carbon Hill Still Boosting Funds for Inaugural Trip,” The Mountain Eagle, January 6, 1961, p. 2.

[46] Roy Mayhall to Valeria Wyers, January 9, 1961, private collection. I haven’t been able to match the UMW to a specific contribution.

[47] “Committee Successful in Raising Money for Band,” The Mountain Eagle, January 16, 1961, p. 1-2.

[48] Travis Wolfe, “Carbon Hill High Band Leaves for Washington,” Birmingham Post-Herald, January 18, 1961, p 2.

[49] Bill Jones, “Parade Seen by Entire Nation,” The Mountain Eagle, January 23, 1961, p. 1-2; Paul South, “Carbon Hill Band Was There, Too,” Daily Mountain Eagle, January 21, 1993, p.1.

[50] Wolfe, “Carbon Hill High Band Leaves for Washington;” “Carbon Hill Band Marches in Inaugural Parade,” Alabama School Journal (March 1961) in Valeria Wyers scrapbook; Barry Bingham, Jr., NBC News, to Carbon Hill High School, care of Valeria Wyers, January 10, 1961; Carl Elliott to Valeria Wyers, January 23, 1961; all private collection. Elliott noted coverage of the band on both NBC and CBS.

[51] South, “Carbon Hill Band Was There, Too,”

[52] “Toastmistress Club Conducts Meeting,” Daily Mountain Eagle, July 2, 1962, p. 8.

[53] John Sparkman to Valeria Wyers, January 26, 1961, private collection.

[54] “Area Briefs,” Daily Mountain Eagle, p. 1.

[55] At the time, Alabama’s governors were term limited. George Wallace later succeeded in having the term limits repealed and served two more terms. Lurleen Wallace died of cancer in 1968, sixteen months into her term.

[56] Carl Elliott to supporters, May 23, 1966, private collection.

[57] Jones, “Mrs. Woodrow Wyers.”

[58] “Mother Tours Washington While Nancy Celebrates,” The Mountain Eagle, February 1, 1961, p. 2.

[59] Mary Allen To Valeria Wyers, March 25, 1962, private collection.

[60] See Robert Dewitt and Jerry Gray, “In Alabama, an Ailing Town Takes Another Knock,” The New York Times, November 11, 2002, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/11/national/in-alabama-an-ailing-town-takes-another-knock.html; Jeffrey Gettleman, “Tornado Rips Tradition From a Town,” The New York Times, November 13, 2002, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/13/us/tornado-rips-tradition-from-a-town.html.

[61] When Alabama’s 1953 “right-to-work” law became enshrined in the state constitution in 2016, it capped off a decades-long decline in unionization. See Ralph Chapoco, “Alabama Unions Grapple with Right-to-Work Laws,” Alabama Reflector, September 4, 2023, https://alabamareflector.com/2023/09/04/alabama-unions-grapple-with-right-to-work-laws/.

[62] United States Census Bureau, Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Alabama: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, accessed November 6, 2024, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-total-cities-and-towns.html.

[63] “Carbon Hill Memories,” Facebook, posts December 31, 2021, and December 13, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/groups/163619431587/search/?q=band%2C%20Kennedy. Still, the postwar realignment of Alabamian voters to the Republican Party took longer in Walker, which continued to vote for Democratic presidential candidates until the 1984 election. See Election Results Archive – President – General Elections, 1976-2012,” Alabama Secretary of State, accessed November 2, 2024, https://www.sos.alabama.gov/alabama-votes/voter/election-data.