Capucine Rullière

Capucine Rullière is a PhD candidate at the École Normale Supérieure – PSL in the creative program SACRe, where she conducts practice-based research. She works at the intersections of literature, Californian history and sound studies. She is interested in practices of listening that renegotiate ontological and political boundaries of Californian society. Her research includes the making of a sonic essay based on field recordings, found sound and audio archives.

“Baby Shark,” Helicopters and Quiet Hours: Attuning to the Auditory Politics of the UCLA Student Protests

Helicopters roaring, picketers breaking into chants, counter-protesters blasting Hebrew pop songs, and, at times, an eerie silence: jarring dissonances reverberated across the campus of the University of California, Los Angeles as student protests unfolded last spring. In the wake of nationwide pro-Palestine demonstrations, protesters set up camp near Royce Hall to demand that the University of California divest from $32 billion assets invested in weapons manufacturers and other companies funding the war in Gaza[1]. After the encampment was violently attacked by counter-protesters on the night of April 30, LAPD officers and private security were dispatched and eventually dismantled the camp, leading to more than 200 arrests.[2] The eruption of police on campus incentivized UC graduate students to vote a systemwide union strike over the administration’s handling of the protest.[3]

While skirmishes with the police were exploited for spectacular images, the sonic atmosphere often took center stage in accounts of the events. Depictions of a distressing soundscape abound, with students recalling “[counter-protesters] playing recordings of a variety of sounds, including a baby crying and sirens,”[4] “screeching soundtracks,”[5] “police helicopters hovering [and] the sound of flash-bangs.”[6] Moving away from ocularcentric conventions of reporting, journalists and witnesses often preferred to rely on sounds.

There are many reasons why aural descriptions were a privileged mode of narration. For those of us working at UCLA during the Spring quarter, political action on campus was sometimes hidden to the eye but always remained audible. As an instructor teaching on campus almost every day, and like many of my students and colleagues, I found myself immersed in a sea of sounds—the roar of helicopters, protest songs, rallying cries sometimes devolving into an eerie silence—. Many of us navigated the campus by ear, for sounds carried information and affects beyond zones foreclosed by the police or the administration[7] and provided a counterpoint to visual framings by the media. As events of/in motion, sounds disperse and linger, reconnect disjointed spaces, bodies, affects and intimacies. In this sense, listening to the sounds of the protests is an affective and situated mode of knowledge production.

For protesters, counter-protesters and for the police, a wide array of sonic practices were mobilized to regain discursive and physical control of the campus. Drawing from the genre of noises of protest is an important strategy to legitimate and historicize protesters’ speech vis-a-vis a broader history of protest movements. Furthermore, for marginal and under-represented groups especially, making noise during a demonstration is a crucial strategy when politics of visibility fail. In his exploration of the political potentialities of sounds, Brandon Labelle argues that auditory practices can destabilize the ontological hierarchies established by specular politics of representation. The synesthetic rearrangement of our senses, he suggests, reorients us towards those who live “on the edge of appearance,”[8] “relating us to the unseen, the non-represented or the not-yet-apparent.”[9]

The shift away from the eye towards the aural reflects the contagious power of sounds to circulate ideas and affects, unnerve and excite. But sounds are unstable and difficult to manipulate; they degrade quickly; they are constantly mediated in series of physical transductions and subjective perceptions. The ambiguous nature of sounds and of our listening, or what Labelle calls their “weakness,”[10] also endows them with an agentive potential for insurrection and resistance: sounds can excite the senses, circulate among bodies, gather or repel crowds, disrupt everyday life.

What was at stake, then, seemed to be the political, agentive, possibilities offered by a range of auditory practices. More specifically, the sonic atmosphere catalyzed legal and ethical points of contention in a heated argument—sometimes even more so than students’ demands—, as each party accused the other of making the campus an unsafe labor environment. In May, the United Auto Workers (UAW), the labor union representing 48,000 UC graduate students, contended that the university had changed free speech policies without notice and failed to protect students, resulting in degraded work conditions. The university argued in turn that the strike was unlawful because it was motivated by political concerns unrelated to labor contracts. Their claim was rejected twice before an Orange County Superior Court judge issued a temporary restraining order on June 7, effectively ending the strike.[11]

This article explores how sonic and aural practices were deployed in an atmospheric conflict. I engage with notions of sonic permeability and sonic agency[12] to understand how noisemaking and listening prompted a rearrangement of entangled affects, bodies, knowledge and representations. Such a redistribution, I argue, heralded the emergence of conflicting conceptions of academic labor and of the campus as public space.

I begin by focusing on sounds of the occupation and labor strike. I examine the sonic practices developed in the construction of discursive counterpublics[13] within the public sphere of the campus. Then, I analyze the radical shift in the sonic topography of the campus when the police responded to the occupation. The infiltration of policiary sounds in the university and domestic spaces point to the growing militarization of sounds and shifting roles for academic speech and labor. Thus, analyzing how sounds disrupt work and intimate life on campus may bring new perspectives on the labor strike that ensued and question what future is left for the American campus as a public sphere.

A Note on the Definition of Sonic Atmosphere

“Unsettling and dissonant [noise] (…) a running torrent of loud, disturbing sounds,”[14] a thunderous noise,”[15] “[the encampment] bombard[ed] with loud noises played over speakers”[16]… As flocks of journalists congregated to bear witness to the rise and fall of the UCLA pro-Palestine encampment, aural descriptions of the protest flourished in the press. Unusual sounds of seemingly ominous significance (like a Hebrew version of “Baby Shark” playing on repeat)[17] were sometimes discussed; yet most descriptions of the sonic atmosphere remained nebulous, alluding to a cacophony of helicopters hovering over the campus, counter-protesters blasting music, union members rallying with megaphones. The persistent usage of hypernyms like “noise” and “sounds” in articles about the protests is symptomatic of the difficulty to come to grips with the causes, manifestations and effects of sonic atmospheres, let alone when they are the site of an open political conflict.

As events in flux, immaterial and ever-changing, sounds elude essentialization. The trouble with defining and describing a sonic atmosphere, then, may stem from its slippery, evasive nature. An extensive body of scholarly work is concerned with finding linguistic, prosodic, cultural or even technological tools to trace the contours of sound and atmosphere. While I do not seek, in this article, to retrace the historical evolution of these key concepts, I propose to pair Steven Feld’s relational acoustemology with Teresa Brennan’s concept of the atmospheric subject to come to grips with sonic atmospheres from a relational perspective. Feld first developed a theory of acoustemology in his seminal ethnographic study Sound and Sentiment (1982),[18] which paved the way for the emergence of sound studies. Observing the sonic forms of expression circulating among the Kaluli people of Papua New Guinea and the interactions between the Kaluli and their (non)human environment, Feld argued for the existence of specifically sonic forms of knowledge production. Combining acoustics with epistemology, acoustemology allowed him to conceive of “sound as a capacity to know and as a habit of knowing.”[19] In other words, Feld invites us to think of sounds as relational events, mutually producing and produced by a set of social, affective, cultural and technological knowledge.

The theory of acoustemology presupposes the existence of a listening and/or sounding subject (or, at the very least, an entity[20]) in relation to its sonic environment. Likewise, Brennan takes a relational approach to atmosphere and criticizes modern theories of a contained subject. Working from the observation of movements of affective transmission in various settings and crowds,[21] Brennan postulates instead a fundamentally permeable being, “not affectively contained.”[22] Thinking about the listening and sounding subject from Brennan’s porous, permeable ontology may be helpful to understand sonic relations—how sounds propagate, circulate, affect listening, and transform subjects and their environments.

Following Feld and Brennan, a sonic atmosphere could be broadly defined as an ongoing process of fabrication, modulation and circulation of affects, relations and knowledge shared in the presence of sounding and listening subjects. I propose to employ this definition to attune to the collective circulation of affects produced or enhanced by sounds. In the case of protest crowds, adopting this perspective brings us closer to an environmental imagination of bodies in relation, whereby we can examine collective dynamics of sensuous contagion among demonstrators and their public. This definition may clarify how intertwined networks of sounds and affects inform collective action, produce shared knowledge and give shape to public voices and spaces—that is to say, how “weak,” seemingly ethereal sounds, can paradoxically be the catalyzer for political agency.

Sonic Repertoires of Protest: Reclaiming Political Agency via Sounds

In the encampment or on the picket line, demonstrators at UCLA displayed a sonic repertoire belonging to a long history of protest culture and political action in the United States. The sonic mise-en-scène of the labor strike and of the pro-Palestine protests was mostly based on slogans, songs and rhyming chants amplified by bullhorns. Sonic staging has a performative function: appropriating traditions of sonic resistance and dissent, the group signals its adherence to received forms of protest culture. As a result, protesters render their actions legible historically and can gain legitimacy among a wider public. A typical example of this strategy is the use of bullhorns: because megaphones significantly distort speakers’ voice, we can infer that demonstrators do not use them solely to convey speech to a large public than to signal themselves as a protesting crowd willing to make use of the common vernaculars of political action. The voice distorted by amplification may lose discursive clarity (sometimes to the point of unintelligibility) but gains space and can be heard as a voice of dissent. Making use of sounds’ indexical properties, protesters assert their presence and situate their action vis-à-vis a long history of labor movement and political action: sonic practices legitimate a current political action under the aegis of protest culture. Adhering to the genre of protest noise, students construct a legible framework for their demands; the process of historicization warrants their presence, even when disruptive.

At UCLA, the chants and calls that resonated on campus formed a vast melting-pot of distinct historical references. Some slogans were targeting UCLA Chancellor Gene Block or the UC administration; others were mentioning the Palestinian uprisings or denouncing the power of the United States military. Other chants, however, were referring to a broader history of student activism. Slogans like “The whole world is watching” or “Peace for Protest” referred to the anti-Vietnam war protests in particular, a tipping point in the history of student activism in the United States. The connection drawn between campus protests, past and present, is not surprising and can be understood in light of the struggle to legitimate the pro-Palestinian occupation. References to past student protests have a special resonance at the University of California, where the twentieth-century history of student protests is undergoing a major process of institutionalization. The history of the Free Speech Movement is publicly promoted, advertised and endorsed by the University, from names of campus cafes to programs of equity, diversity and inclusion. Thus, the reference to student activism appears to be part of a specific conversation surrounding a perceived discrepancy between the University of California’s public image and its silence.

The most spectacular sonic strategies, however, may have been those employed by counter-protesters. In fact, before people in the encampment were attacked on the night of April 30, political conflicts on campus were mostly waged on the terrain of sounds. Soon after students set up tents, counter-protesters proceeded to install a giant screen and loudspeakers next to the encampment. In a TV news report for Fox 11 Los Angeles, a journalist describes the scene: “right now, it sounds like a concert. I can barely hear myself speak. The counter-protesters supporting Israel are blasting music so that the demonstrators inside this camp can’t hear what they’re doing. It appears to be working, at least for now, I can barely hear myself talk (…) you can’t hear anything about what’s happening inside.” In the background, counter-protesters wearing Israeli flags jump and dance to the sounds of techno music, while people in the encampment try to listen to a speech. A flabbergasted anchor recapitulates the scene: “essentially what’s happening right now is the Jewish students or pro-Israeli students are blasting music, much of it Hebrew music, so that these other folks are so annoyed that they leave, is that what’s happening?” Meanwhile, the camera pans to reveal a stark discrepancy between the festive atmosphere of the Israeli counter-protest, with demonstrators dancing in the sun, and the quiet retreat of people in the encampment, regrouping as far away from the loudspeakers as they can.[23] The counter-protesters’ aim is to drown out sounds to reclaim physical or acoustical control over the campus, and to create affective dissonance by staging a festive mood: political conflict unfolds via the fabrication of a jarring sonic atmosphere.

The journalist’s incredulity seems to arise from the uncanny aspect of this tactic. Around the same time, counter-protesters set up an outdoor screen and loudspeakers to blast pop songs and play on loop a propaganda clip from the Israeli military showing gruesome images from the October 7 attacks. The Los Angeles Times recorded, “[t]hey set up a giant video screen near the camp that played and replayed videos of Hamas militants. They broadcast a running torrent of loud, disturbing sounds over a stereo — an eagle screeching, a child crying — and blasted a Hebrew rendition of the song “Baby Shark” on repeat, late at night, so that campers could not sleep.” Demonstrators, when interviewed, often described the strategy as “psychological attacks.”[24] Indeed, the repeated use of pop music and disquieting sound effects is a disturbing echo to the military use of sound and music by the US army. In Sonic Warfare (2010), Steve Goodman traces the origins of this military history back to the Urban Funk Campaign, a psychological operation that gestated during the Vietnam War. The US military would blast loud rock music from helicopters flying above the jungle at night to prevent enemies from sleeping and instill fear.[25] Two decades later, the FBI “play[ed] high-volume music blended with sound effects into the compound of the Branch Davidians led by David Koresh with a playlist accompanied by bagpipes, screeching seagulls, dying rabbits, sirens, dentist drills, and Buddhist chants.”[26] These distant echoes project the UCLA protests into a globalized history of violence, where noise is recuperated for modern psychological warfare.

Sounds of Occupation: Elaborating Counterpublics

The encampment’s lineage can be traced back to the Occupy Movement of 2011 and further back to the 1968 anti-war protests. But, at UCLA, another point of reference was the 1985 historical occupation of the campus. Students had rallied and organized a sleep-in at Murphy Hall, home to the Chancellor’s office, to demand that the university divest from South Africa’s apartheid government and drop charges against demonstrators arrested in Berkeley. It was the biggest student protest since the Vietnam War and resulted in the largest university divestment at the time (the UC Board of Regents divested $3.1 billion from companies doing business in South Africa)[27]. The 2024 protests were based on a similar strategy to occupy public spaces to reclaim them as countercultural discursive spheres. For a large campus like UCLA, walkways and plazas are liminal spaces, usually meant to be traversed or to provide temporary solace from crowded classrooms. But, for students, the occupation offered the opportunity to revisit the campus’s public and discursive potential. Squares and plazas allowed for large gatherings and encounters. When many protesters filed into these spaces, the campus became a site of public resistance to institutional policies.

Following Nancy Fraser, the encampment could then be defined as “subaltern counter-publics.” Working to question and expand Habermas’s thought, Fraser argues that within the public sphere, there exists “parallel discursive arenas where members of subordinated social groups invent and circulate counter discourses, which in turn permit them to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs.”[28] Although counterpublics “function as spaces of withdrawal and regroupment”[29] away from institutions of the public sphere, they intersect with the dominant public sphere. This intersection is a necessary condition for the circulation of alternative discourses and self-representations conceived in the counterpublics. The UCLA encampment falls under such definition, being a site where students gathered to elaborate alternative discursive strategies, thoughts and political practices. While college students have higher social privileges than many other subordinated groups working for the university, they still hold a dominated position in the university, having little control over the organization of their labor, time, and social life. Their speech, affects and discursive agency are filtered through academic language and contained by the social and physical architecture of the university. The protests also revealed students’ precarious status; many universities across the country threatened to expel them, to withhold their wages, and to revoke visas or legal documents for international and undocumented students. The occupation, as a genre of political action, destabilizes this relationship of domination by interrupting labor, disrupting the academic calendar, and generating unmediated and decentralized speech. Withdrawing from assigned discursive zones, students construct representations and desires for the university, revisit their place within it and their possible involvement in its policies. What is produced within the encampment can then be re-circulated to academics and to a broader public.

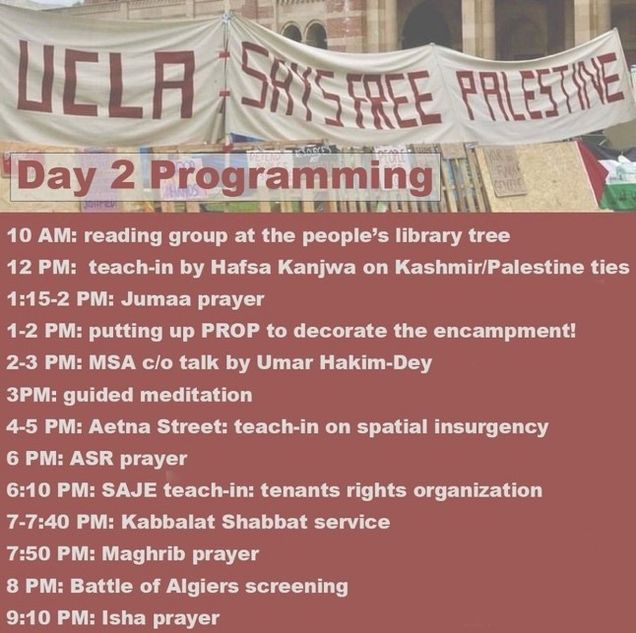

In the occupied space of the encampment, students’ redefinition of individual and collective identity percolates through a set of distinctive sonic practices mentioned in the schedules below (fig.1 and fig.2).

Time was made for songs, prayers, guided meditation and talks, activities that strengthen social bonds and foster circulation of knowledge and affects. The schedule of quiet hours from 10pm to 6am, however, seems to participate in the constitution of collective identity in slightly different ways. Students’ silence can be construed as a form of withdrawal that Fraser sees as the necessary condition for the constitution of counterpublics. As they withdraw from the noisy sphere of protest for the night, protesters rebut—if only momentarily—their portrayal as a disruptive group. In the racially diverse space of the encampment, reclaiming quietness and silence undermines racist representations surrounding the perceived noisiness of subaltern bodies and cultures. A concept widely spread in Western urban and suburban life, quiet hours are part of conventional representations of politeness and civility. Negotiating quietness as much as disruptive noise, students reconfigure ontological representations of the subaltern body and voice. They destabilize and rearrange “acoustic assemblages,”[30] a concept coined by Ana Maria Ochoa Gautier to define the “the mutually constitutive and transformative relation between the given and the made that is generated in the interrelationship between a listening entity that theorizes about the process of hearing producing notions of the listening entity or entities that hear, notions of the sonorous producing entities, and notions of the type of relationship between them.”[31] Acoustic assemblages are a set of relational and cultural interpretations of the other and are mutually produced in the interaction between listening and sounding entities. The equation of silence with civility, and of certain sounds as noise, are altered in the space of the encampment. Qualities attached to institutional silence are transposed, and values attached to intellectual knowledge and culture are relocated away from classrooms to the encampment. Political and ontological representations shift as protesters sound out their identity to refract it back to the wider public sphere of the campus.

The fabrication of collective silence may have weaknesses. Silence is a fragile form of withdrawal; it can break, be covered up by other sounds, and rendered inaudible. Yet silence can paradoxically hold agentive potential for the elaboration of collective representations.[32] It offers the opportunity to withdraw and regroup, which allows individuals to attune to their sonic and affective environment, to the presence of others, to the collective fabrication of a political praxis. Thus, the political relocation of speech and silence in and out of the encampment reconfigures the public discursive sphere of the campus. Administered collectively, the encampment is potentially a space of the commons in dialogue with wider discursive spheres.

A Sonic Topography of Surveillance

After the encampment was attacked by outside protesters on the night of April 30, the police were dispatched. In a context of mounting tension, the soundscape of protest suddenly changed. Students and faculty members deserted the campus after the university temporarily switched to remote learning, and, by late May, the union strike was resonating outside. The most striking sound was the chopping noise of the helicopters that hovered, day and night over the university and Westwood Village. The sound is not uncommon in Los Angeles—the LAPD possesses the largest helicopter fleet in the world, with 17 choppers and over 90 employees.[33] The program is the only in the United States to operate 24 hours a day. Helicopters are an ominous soundmark of the city, what Raymond Murray Schafer’s calls “a community sound which (…) possesses qualities which makes it specially regarded or noticed by the people in that community.”[34] Soundmarks are a key element composing the soundscape, the auditory environment perceived by a listening subject. Schafer elaborated his theory of the soundscape as a rebuttal of the forces of a globalized world that, he said, had reached an “apex of vulgarity.”[35] Concerned with the nefarious effects of industrial noise on people’s health and morals, he advocated for the preservation of cultural and natural soundmarks, a strategy similar to politics of patrimonialization. Schafer, then, ascribes a positive value to soundmarks. Helicopters in Los Angeles, however, represent the negative counterpart to the Schaferian soundmarks, an infamous nuisance. Ever since the LAPD began developing its fleet in the aftermath of the 1965 Watts Riots, residents have ceaselessly complained about aircraft noise and have accused the LAPD of discriminating against certain neighborhoods. Pressed by citizens, social activists and noise pollution agencies, city controller Kenneth Mejia ordered an audit of the LAPD in 2023. Its office released a scathing report of LAPD’s use of its helicopter fleet, concluding that “the LAPD’s current use of helicopters causes significant harm to the community without meaningful or reliable assessment of the benefits it may or may not deliver.”[36] They estimated that the Air Support Division (ASD) costs $46.6 million a year, or almost $3,000 per flight hour.[37] The audit underlined that most flights are not devoted to high priority events but are used for regular patrols, transportation or ceremonial fly-bys; and that there is no significant evidence correlating helicopter use with crime reduction.[38] Helicopters fly a disproportionate amount of time over some neighborhoods, a strategy of noise harassment incentivizing fear and collective annoyance. The predominantly Black and Latino district of South Central sees the highest number of air patrol operations: they represent 9% of total ASD flight time although the crime rate stands at 6.4%. Conversely, helicopters fly relatively rarely over the affluent neighborhoods adjacent to UCLA: in West Los Angeles, ASD activity is lower (2.7%) than the local crime rate (4.6%).[39]

As city soundmarks, helicopters are the symbolic repository of a history of violence and segregation that has scarred the topography of Los Angeles. Although the proclaimed mission of the ASD is to “reduce the fear of crime.”[40] helicopters are akin to alarm systems and propagate fear. Rather than signal the response to a menace, the chopping noise of helicopters is interpreted as the presence of a threat in one’s immediate vicinity, a hermeneutical slippage that contributes to the fabrication of a sonic imaginary of crime and violence. And, once this is funneled into an affective reality, fear warrants helicopters’ presence on the newly-designated zones of danger.

As LAPD helicopters fly above UCLA, the campus is enclosed within a policed topography in sharp contrast to the encampment’s common space. The perimeter they delimit is visual and sonic: upon hearing rotor blades chopping the air, students know they are exposed to the police’s gaze. Sound demarcates the invisible limits of a sprawling zone of surveillance. The campus is reframed as a spectacular stage of conflicts. From above, local spaces and politics are rendered invisible and inaudible; from below, sounds of helicopters, drones, police sirens, are at times heard without their source being visible. Hearing sounds without seeing who or what entity produces them is what Michel Chion, enriching Pierre Schaeffer’s definition, calls “acousmatic”[41] sounds. Chion remarks upon the disproportionate force of the acousmatic. The “acousmêtre,”[42] the entity we hear without seeing, has the power to remain hidden while signaling their ubiquitous presence: they are endowed with “omniscience and omnipotence.””[43] According to Chion, the history of acousmatic sounds can be traced back to a Pythagorean sect whose master would deliver their speech from behind a curtain, hiding himself from his disciples; and further back to the voice of an unrepresentable God, whose demiurgic power is entirely contained in their voice; and further still to an original perception of the voice of the Mother.[44] The voice of the acousmêtre is the immaterial embodiment of these demiurgic voices, exerting their power and displaying seemingly limitless knowledge. In the same way, the police’s acousmatic dispositif indexes their towering presence, suggesting that they can potentially be everywhere and see everything—what Chion understands as powers of ubiquity and panopticism.[45] Sounds index the capacity for the disciplinary apparatus to materialize at will and to remain hidden from view. State surveillance becomes a phenomenological experience.

Thus, aircrafts, like sirens and megaphones, transform public spaces in at least two ways. Firstly, their presence reorients the way we listen to our surroundings with fears for our safety. Secondly, they physically augment the policiary gaze and voice, turning public spheres into monitored spaces. The sonic policing on the UCLA campus eventually led to the demise of the counterpublic space of the encampment.

Policing Intimacies

Deployed in a conflict waged on atmosphere, helicopters are part of a “sonic warfare” that Steve Goodman convincingly defines as “the use of force, both seductive and violent, abstract and physical, via a range of acoustic machines (biotechnical, social, cultural, artistic, conceptual), to modulate the physical, affective, and libidinal dynamics of populations, of bodies, of crowds.”[46] As an acoustic technology, they are engaged in a struggle to modulate affects and information and reshape representations of social and physical space.

Some of these effects are registered by the science of acoustics. Time and again, studies have shown the potential harms resulting from exposure to helicopter sounds. The Fly Neighborly Committee, which develops noise abatement programs, found that helicopters flying below 1,000 feet over the ground exceed the threshold of noise sensitivity, capped at 65 dB(A).[47] The ASD manual, by comparison, recommends flying above 800 feet. and in reality, LAPD helicopters usually fly between 500 and 700 feet above ground level.[48] At this altitude, helicopters certainly reach the 85dBA threshold of harmful sound for populations.

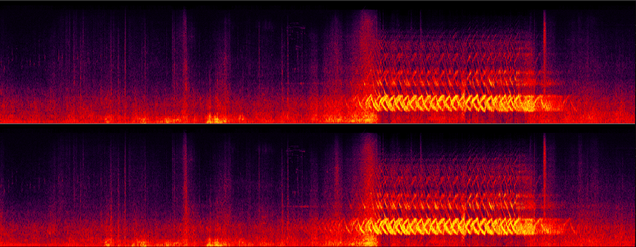

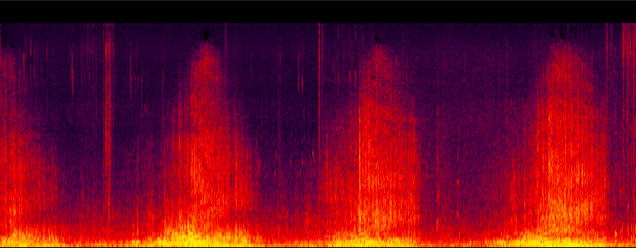

The following field recording of helicopters and car sirens (a) captures a moment where this threshold was exceeded. Although I have capped the decibels output, you can still hear and feel the helicopters and sirens’ shrilling noise-effect. Reproduced below are the spectrogram corresponding to field recording (a), which I made in my apartment in Westwood (fig. 3), and a second spectrogram corresponding to a recording of helicopters and birds that I made at the UCLA Sculpture Garden (fig. 4). The two documents read as the visible inscription of a policiary sonic architecture. Helicopters form large columns of sound, taking up a broad bandwidth space, while sirens extend over time in intertwined frequencies of high intensity. Aircraft noise blankets all sound, leading to sonic depletion; only in the interstices between two flights of helicopters does the twittering of birds remain visible on the spectrogram (fig. 4). The spectrograms show how the police’s acoustic technologies dramatically dominate space to reconfigure it in accordance with their own rhythms and intensity, and how they raze the soundscape, smoothening out its granularity. The homogenization of our audible environment deteriorated sonic politics. There could be no attuning to the silence coming from the encampment during quiet hours; no registering of the vibrations of drums during marches; no collective practice of chants and songs. What eventually disappeared were “expressions of critical togetherness[49],” sounds of resistance and dissent that allowed for a sensuous reckoning and elaboration of the collective.

Spectrograms can exhibit mechanisms of auditory degradation, but they fail to account for the affective, felt effects of sound. Here, the relationship between sounds of the police and an ambient sense of dread remains invisible, eluding the framework of acoustics. I remember it vividly, yet it is difficult to come to grips with sounds’ elusive “affective tonality.”[50] This prompts the question of how to devise a language that can account for sounds’ materiality and relationality. Thinking from his experience as an electronic musician and producer, Steve Goodman invites us to think of sounds as vibrational forces evolving in a field of porous bodies and minds. This perspective, he argues, evinces how acoustic technologies are weaponized to produce atmospheres of dread and fear. I propose to adopt Goodman’s vibrational perspective to listen to the following field recordings. How are the vibrations of helicopters weaponized, and how are their movements controlled? What affective field do they create?

Helicopter sounds are characterized by low frequencies of high intensity visible in bright yellow on the spectrograms. Such frequencies, Goodman suggests, are part of a multisensorial “nexus of vibration”[51]—below 20Hz, sound waves are vibrations, meaning they can be felt via our sense of touch. Even sub-bass vibrations can be registered by the body: they reverberate on vibrational surfaces in our surroundings, changing the atmosphere of a space, producing micro-movements of air and matter that can be felt sensorially and/or affectively. As multi-sensorial listeners, we find ourselves enveloped in this world of (sub-)bass vibrations.

In the multisensorial perception of bass, senses are rearranged, redistributed. The bass sounds construct “a vectorial force field—not just heard but felt across the collective affective sensorium.”[52] Upon hearing a helicopter, our perceptions are reoriented away from the visual and towards the audible (and the tactile); hearing takes primacy over other senses, reaching a mode of “sonic dominance.”[53] To Goodman, this sensuous rearrangement results in homogeneous perceptions, “a flatter, more equal sensory ratio.”[54] Thus, not only do helicopters degrade the soundscape, they homogenize our very listening. As we feel our environment shrinking, our senses diminished, our body traversed by policiary vibrations, a collective sense of dread and fear emerges.

Recordings (a) and (b), made from my bedroom and kitchen in Westwood, are my attempts to make audible how sonic vibrations penetrated domestic spaces. Homes in Los Angeles are very permeable to sounds, reverberating tremors and vibrations quite generously. In the semi-arid climate of Southern California, house architects have long privileged open spaces and seamless fluidity between the indoors and the outdoors, allowing for the circulation of oceanic breezes in an area with low need for thermal insulation[55]. Homes become spaces of contagion inhabited by vibrations. In the context of a shift to remote learning, intimacy as much as intellectual labor are exposed to viral police sounds. Paradoxically, values of disembodied and delocalized labor were promoted precisely when, as students and university workers, we experienced the inevitable connection of intellectual work to the body, attuning to a phenomenology of academic labor. Considering this experience, the union strike against unfair labor practices may be understood as a response to the contagion of repressive sounds in intimate and public lives, as they reverberated across flesh and glass, domestic spaces and the workplace.

Outlawing Noise: What is the Future for the Campus as Public Sphere?

Over the summer, the University of California prepared new guidelines for free speech to ensure the safety of all students on campus. The California State Budget threatened to withhold $25 million in funding until the UC administration devised a systemwide framework for free speech.[56] In response to these demands, the UCLA administration introduced a series of dissuasive measures. The Board of Regents also approved UCPD’s requests for less lethal munitions. They concern additional drones, pepper balls, a kinetic breaching tool and munition launchers.[57] The UCPD report also makes note of a sound cannon by the UC Berkeley and UC Santa Cruz police. Sound cannons are long range acoustic devices (LRAD) developed for the Navy. They propagate sound waves in any direction and produce a loud, high-pitched sound. LRAD signal danger, communicate across long distances, and repel and scatter crowds. They operate within the frequency range most sensitive to human ears, between 200 Hz and 10,000 Hz (roughly the range of human speech), and they can emit extremely loud sounds, up to 140dB-160dB.[58] At the higher level, sound can cause immediate pain, physiological side effects such as nausea, fainting, or permanent hearing damage, and instill fear. The LRAD was utilized in more than 250 American cities, especially in liberal protests, such as anti-Trump activism, Black Lives Matter, and the Occupy Movement.[59] The UC Berkeley police stated that LRAD is for crowd control management. Yet the acquisition appears to be the latest instance of a sonic technology being deployed in a war waged on atmosphere.

In parallel to police rearmament, UC President Michael Drake announced a series of new free speech measures, including a ban on campus encampments that specifically targets occupation organizing (food distribution, drawing or writing on buildings with chalk, camping equipment are prohibited).[60] The measures also introduce new rules surrounding sound. At UCLA, the “Time, Place and Manner (TPM) policies,” which regulate public use of UCLA property, is revised. Two notable changes concern the designation of “areas for public expression” and new regulations on the use of amplified sound devices.[61] “Public expression activities,” which UCLA defines as “leaf-letting, marches, picketing, protesting, speech-making, demonstration, petition circulation, distribution and sale of non-commercial literature incidental to these activities, and similar speech related activities,”[62] are restricted to free speech areas. Formerly occupied areas of Dickson Plaza, Kerckhoff Patio and Dodd Hall are not designated as zones for public expression. In other areas, prior approval for event organizing must be requested from the administration at least ten days in advance.[63]

UCLA also restricts the use of amplified sound devices including bullhorns, portable speakers, electronic amplifiers, drums and any form of a manual noise maker. Amplified sound is banned during marches, unless approved by the administration beforehand. In areas that allow for public expression, amplified sound is allowed one hour a day, from 12pm to 1pm, with the exception of BruinWalk, a bustling strip where clubs, fraternities and religious proselytes hand out flyers to busy students. Amplified sound is forbidden in front of the Kerckhoff Hall administrative buildings and the main entrance of campus at all times. Sounds and free speech practices are deemed by the university administration as “disruptive” and are forbidden.[64]

The creation of free speech zones and regulations surrounding protest sounds aim to restrict or make illegal labor organizing strategies. Because the administration is limited in its power to regulate public speech, it resorts to noise regulation to contain and control its circulation. Perceived disruptions of academic work are prohibited: in other words, restrictions are imposed on strikes themselves, defined as workers’ interruption and disruption of labor. The new sonic topography imagined by the university reflects a radical shift in thinking about the relationship between the campus and the public sphere. Campuses appear to be undergoing a process of depublicization. In Kantian terms, publicity relates to the disclosure and discussion of state legislation and matters of common interests by private individuals gathered in public.[65] The depublicization of the public campus challenges academic work, which relies specifically on the voluntary gathering of individuals to facilitate the free circulation and mutual elaboration of critical thinking. The campus—classrooms, but also the outdoors, the gym, cafes and other informal spaces—is, traditionally, a site of student sociality enabling a type of study that Fred Moten defines in The Undercommons (2013) as “what you do with other people. It’s talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice.”[66] It remains to be seen how this form of study will be affected by the foreclosure of counterpublic spaces on campus.

Conclusion

Questioning the political potential of sounds, Labelle poses the following question: “What particular ethical and agentive positions or tactics may be adopted from the experiences we have of listening and being heard? Might the knowledges nurtured by a culture of sounding practices support us in approaching the conditions of personal and political crisis?”[67]

In the context of the pro-Palestinian protest and labor strike at UCLA, a wide array of sounding and listening practices were appropriated; they served multiple purposes. From the perspective of acoustemology, listening to the sounds of the protests was a dialogic mode of knowledge production. Sonic references to the history of campus protests, the use of silence, prayers and songs, participate in the construction and circulation of information about global and local politics. This type of knowledge-making points to alternative forms of public education at the university.

On the campus, the sonic technologies and auditory practices employed were part of a struggle to reclaim the public discursive space of the campus and its atmosphere. The viral and contagious nature of sounds were mobilized in strategies of dissent and resistance. Sounds move across bodies, inhabit intimate and public spheres, conjure distant spaces and memories. Sounds hold agentive and relational promise in their itinerant dimension. For many students, then, sounds of the protest were a means of affective resistance to disembodied and depublicized labor. Sonic and aural practices were instrumental in the elaboration of counter-publics from which students could gain discursive agency, revisit their identity and negotiate their position vis-a-vis the university. In this sense, sonic strategies were connected to an alternative form of academic labor, which consisted in elaborating a collective political voice and revisiting what the campus, as a public workplace, can stand for.

It is not yet clear how the new restrictions on noise will affect this academic work; but new forms of sonic resistance might emerge and reverberate across the space of the campus.

[1] Michael Burke, “UC Has $32 Billion in Assets Targeted by Pro-Palestinian Protesters, but No Plans to Divest,” EdSource, May 14, 2024, https://edsource.org/2024/uc-has-32-billion-in-assets-targeted-by-pro-palestinian-protesters-but-no-plans-to-divest/711864.

[2] Neil Bedi et al., “How Counterprotesters at U.C.L.A. Provoked Violence, Unchecked for Hours,” The New York Times, May 3, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/05/03/us/ucla-protests-encampment-violence.html.

[3] The UAW Local 4811 labor union represents 48,000 graduate students, teaching assistants, academic researchers, and postdocs from all ten campuses of the University of California, including UCLA. Union members from all campuses voted for a systemwide rolling strike, meaning that campuses were called to strike at different times. Walkouts began at UC Santa Cruz on May 20, 2024 and spread to UCLA and UC Davis a week after.

[4] Jaweed Kaleem, “Judge Halts UC Academic Workers’ Strike, Citing ‘Damage to Students,’” The Los Angeles Times, June 7, 2024, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-06-07/uc-seeks-to-halt-strike-takes-academic-workers-to-court.

[5] Stefanie Dazio et al., “UCLA Cancels Classes after Dueling Protesters Clash on Campus over the War in Gaza,” PBS News, January 5, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/ucla-cancels-classes-after-dueling-protesters-clash-on-campus-over-the-war-in-gaza.

[6] Summer Lin et al., “Mace, Green Lasers, Screeching Soundtracks: Inside the UCLA Encampment on a Night of Violence,” The Los Angeles Times, May 1, 2024, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-05-01/inside-ucla-pro-palestinian-encampment-on-night-of-violence.

[7] During the Spring quarter, the UCLA administration and the police sometimes restricted public access to certain areas on the campus and declared last-minute shifts to remote instruction. Students and (non-)academic personnel were informed via “BruinALERT,” an email system for emergency notifications.

[8] Brandon LaBelle, Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2020), 1.

[9] LaBelle, 2.

[10] LaBelle, 20.

[11] Jaweed Kaleem, “Judge Halts UC Academic Workers’ Strike, Citing ‘Damage to Students,’” The Los Angeles Times, June 7, 2024, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-06-07/uc-seeks-to-halt-strike-takes-academic-workers-to-court.

[12] LaBelle, Sonic Agency.

[13] Nancy Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy,” Social Text, no. 25/26 (1990): 56-80, https://doi.org/10.2307/466240.

[14] Bedi et al., “How Counterprotesters at U.C.L.A. Provoked Violence, Unchecked for Hours.”

[15] Helena Humphrey, “Chaos Unfolds at Gaza UCLA Campus Protest,” BBC, May 2, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-68946573.

[16] Will Carless, “How Pro-Palestinian Camp, and an Extremist Attack, Roiled the Protest at UCLA,” USA Today, May 3, 2024, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2024/05/03/inside-ucla-protest/73560767007/.

[17] Lin et al., “Mace, Green Lasers, Screeching Soundtracks: Inside the UCLA Encampment on a Night of Violence.”

[18] Steven Feld, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression (1982; reis., Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2012).

[19] Steven Feld, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression, 27.

[20] To exist in the world, sound does not necessarily require a living subject but, at the very least, a receiving entity that can be human, animal or technological (for example, a recording device).

[21] Teresa Brennan, The Transmission of Affect (Cornell University Press, 2004), http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt5hh05z.

[22] Teresa Brennan, The Transmission of Affect (Cornell University Press, 2004), 2.

[23] Fox 11 Los Angeles, “Pro-Israel Protesters Blast Music Outside pro-Palestine Demonstrations at UCLA,” YouTube, April 26, 2024), 04:57, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-WfyLT_NfGE.

[24] Lin et al., “Mace, Green Lasers, Screeching Soundtracks: Inside the UCLA Encampment on a Night of Violence.”

[25] Steve Goodman, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (Cambridge, Mass. London: MIT Press, 2012), 19.

[26] Goodman, 21.

[27] Matthew Royer, “Examining Parallels to 1985 Student Calls for Divestment from South Africa,” Daily Bruin, April 25, 2024, https://dailybruin.com/2024/04/25/examining-parallels-to-1985-student-calls-for-divestment-from-south-africa.

[28] Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere,” 67.

[29] Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere,” 68.

[30] Ana María Ochoa Gautier, Aurality: Listening and Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Colombia (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 22.

[31] Ochoa Gautier, Aurality: Listening and Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Colombia, 23.

[32] LaBelle, Sonic Agency, 4-5.

[33] Kenneth Mejia, “LAPD Helicopter Audit,” Audit (Los Angeles: Los Angeles City Controller Office, December 11, 2024), https://controller.lacity.gov/landings/lapd-helicopters, 3.

[34] R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Rochester, Vt.: Destiny Books; 1993), 10.

[35] Schafer, 3.

[36] Mejia, “LAPD Helicopter Audit,” ii.

[37] Mejia, ii.

[38] Mejia, iii.

[39] Mejia, 24.

[40] Mejia, 8.

[41] Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 18.

[42] Chion, 23.

[43] Chion, 23.

[44] Chion, 27.

[45] Chion, 23.

[46] Goodman, Sonic Warfare, 10.

[47] “Fly Neighborly Guide” (The Helicopter Association International Fly Neighborly Committee, 2009), https://www.ormondbeach.org/DocumentCenter/View/199/Helicopter-Assoc-International-Fly-Neighborly-Gui, 7.

[48] Mejia, “LAPD Helicopter Audit,” 43.

[49] LaBelle, Sonic Agency, 5.

[50] Goodman, Sonic Warfare, xv.

[51] Goodman, 28.

[52] Goodman, 28.

[53] Julian F. Henriques, “Sonic Dominance and the Reggae Sound System Session,” in The Auditory Culture Reader, by Les Back and Michael Bull (Oxford: Berg, 2003), 451–80.

[54] Goodman, Sonic Warfare, 27.

[55] For a detailed study of noise pollution in Los Angeles and architectural acoustics in the age of atmospheric vibrations, see Marina Peterson, Atmospheric Noise: The Indefinite Urbanism of Los Angeles (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021).

[56] Teresa Watanabe, “UC Regents: Protests Yes, Encampments No. Campus Rules Must Be Consistently Enforced,” Los Angeles Times, July 15, 2024, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-07-15/uc-regents-say-no-to-encampments-and-codes-must-be-enforced.

[57] UC Council of Chiefs of Police, “UC Police Department Annual Report 2024 of Military Equipment,” Pub. L. No. 481 (AB 481), § Attachment 2 (2024), https://regents.universityofcalifornia.edu/regmeet/sept24/c1attach2.pdf, 5-10.

[58] Lawrence English, “What’s an LRAD? Explaining the ‘Sonic Weapons’ Police Use for Crowd Control and Communication,” The Conversation, February 20, 2022, https://theconversation.com/whats-an-lrad-explaining-the-sonic-weapons-police-use-for-crowd-control-and-communication-177442.

[59] Adam Martin and Alexander Abad-Santos, “Occupy Oakland’s Tent City Is Gone,” The Atlantic, October 25, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/10/occupy-oaklands-tent-city-gone/336367/.

[60] Administrative Vice Chancellor, “UCLA Interim Policy 850: General Use of UCLA Property” (2024), https://www.adminpolicies.ucla.edu/APP/Number/850.0, 2-3.

[61] Administrative Vice Chancellor, “UCLA Interim Policy 852: Public Expression Activities” (2024), https://www.adminpolicies.ucla.edu/APP/Number/850.0.

[62] Administrative Vice Chancellor, “UCLA Interim Policy 850: General Use of UCLA Property” (2024), Attachment A, https://www.adminpolicies.ucla.edu/APP/Number/850.0.

[63] Administrative Vice Chancellor, “UCLA Interim Policy 860: Organized Events” (2024), https://www.adminpolicies.ucla.edu/APP/Number/850.0, 2.

[64] Administrative Vice Chancellor, UCLA Interim Policy 852: Public Expression Activities, 3.

[65] Immanuel Kant, “An Answer to the Question: What Is Enlightenment?” in What Is Enlightenment? ed. James Schmidt (1784; reis., University of California Press, 2019), 58–64, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520916890-005.

[66] Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe New York Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013), 110.

[67] LaBelle, Sonic Agency, 1.