C. G. Branch

C.G. Branch is a current Ph.D. student in American & New England Studies at Boston University. There, they study relationships between reproductive labor, star studies, and the classic Hollywood era.

“Mink Lined Pickets”:

Star Power and the Screen Actors Guild Strikes of 1960 and 2023

“Don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.” — Bette Davis, “Now, Voyager”

‘Star’ Labor: Celebrity Unionizing in Context

Exploitation and entertainment are part and parcel. In Hollywood, rigid hierarchies have long fostered persistent labor precarity for those on and off camera. At critical moments, including the SAG(-AFTRA) and WGA strikes of 1960 and 2023, workers mobilized to demand fairer contracts and better working conditions. While the seductive allure of stardom often obscures the industry’s grueling realities, cycles of withheld labor and union organizing to confront systemic inequities draw attention to the labored dimensions of ‘star’ status.[1] Through sustained focus on the role of celebrity actors in SAG(-AFTRA) in these strikes, it is increasingly clear that that stardom constitutes both a privileged and precarious mode of labor. Integrating a methodology of star studies to explore the complexities of celebrity activism, this research explores the interplay of celebrity, labor, and resistance that animates the strikes of 1960 and 2023, offering insight into Hollywood’s cycles of power, visibility, and worker solidarity within the “dream factory.” In assessing the way public labor disputes are transformed onto the individual body of the star, the privileged visibility of the star becomes a contested site of power.

Stardom: Precarious Privilege

The image of the beautiful, wealthy, and glamorous Hollywood star is integral to the fantasy that the Hollywood machine relentlessly promotes. Within this industrialized context, stars constitute a unique “phenomena of production.”[2] Manufactured by the industry, stars function not only as “merchandise destined for mass consumption,” but as potent symbols that reinforce dominant cultural narratives.[3] That is, the celebrity image shapes and articulates contemporary notions of identity and representation; it is an inherently politicized positionality. Of the vast labor force that constitutes the film industry, stars occupy a privileged position as the highest-paid and most visible figures.[4] In line with the star’s strained subjecthood, this economic privilege is juxtaposed with relative agency. For those few who do ascend to the top of the entertainment hierarchy, the demands of film studios and the constraints of contractual obligations shape their professional lives, revealing the underlying labor structures that govern their careers. Equally, this glamorous façade obscures the reality for many actors, as for every “star,” there are many others who live unsure when their next paycheck will arrive. Those who do manage to make it to the top of hierarchy, ‘Stars,” possess the power to sway public opinion and mobilize collective action.

The first comprehensive study of Hollywood labor, Murray Ross’ Stars and Strikes (1941) opens pointedly; Ross writes, “Hollywood is a union town… The popular conception of Hollywood as a land of make believe is a figment of the imagination.”[5] Labor and entertainment are inextricably bound. Moving beyond a purely fact-based labor exploration, Danae Clarke advocates for a more dynamic interpretation, one that recognizes actors as social subjects navigating embedded labor hierarchies. This approach de-fetishizes the celebrity image and creates space for conversations about labor and political economy within the field of star studies. Contemporaneously, Kate Fortmueller’s Below the Stars: How the Labor of Working Actors and Extras Shapes Media Production is the most comprehensive study of the phenomenon of stars as workers to date, published eighty years after Ross. These works are foundational to an understanding of worker organizing in entertainment. Working in the tradition of such texts, this article seeks to interrogate the role of stardom in labor activism, not merely as an object of consumption but as a catalyst for resistance and a force within the power dynamics of worker solidarity.

When the entertainment machine grinds to a halt—when production ceases, broadcasts fall silent, and cameras stop rolling—the disruption is not merely financial, but cultural. Celebrities, particularly actors, are omnipresent in the reporting of these strikes—not simply because they occupy a visible position in the entertainment industry, but because their involvement, or lack thereof, carries significant ideological weight. Stars are not only performers, but cultural symbols. The star is a sign that signifies glamour, represented materially in the form of opulent lifestyles, lavish homes, and public personas.[6] These class markers are integral to their commercial appeal, making their participation in strikes particularly resonant. For the elite stars—those at the pinnacle of pay and prestige—whose concerns over residuals were often less immediate, their symbolic presence in the labor struggle carries profound significance. It underscores the tension between their relative detachment from the economic struggles of working actors and the broader necessity for solidarity in confronting the systemic inequalities that define the entertainment industry. Thus, star studies not only illuminate the personal stakes of these individuals but also reveal the intricate interplay between celebrity, class, and labor politics, offering critical insights into how labor movements in Hollywood are shaped and understood.

Union Motivation and Residual Resentments

The similarities between the 1960 and 2023 SAG(AFTRA) strikes are numerous, inviting formal analysis. Lasting exactly 148 days each, both strikes grappled with anxieties over new landscapes of mechanization. In 1960, writers and actors demanded residuals for any work aired on television, still a relatively new phenomenon at the time. In 2023, workers sought residual pay from streaming platforms and protections against generative Artificial Intelligence (AI). Both strikes concerned the relationship between art and technology, worker and machine, labor and value. Principally, residuals are at the heart of both conflicts, as writers and stars fought for the value of their labor against a backdrop of rapid technological advancement and industrial realignment. The role of stars in these two strikes offers a lens through which to examine the intersection of celebrity culture and labor politics, revealing how the visibility of actors both on and off the picket lines shapes public perception of these pivotal moments in Hollywood’s labor history.

1960

The 1960 SAG and WGA strikes represent a seismic shift in the historical trajectory of the Hollywood Studio system, not only as an expression of actor exhaustion with the exploitative constraints of studio contracts, but as an indicator of a fracturing media ecosystem more broadly. Things were changing in America, and studios were struggling to adapt. In 1948, the Paramount anti-trust decree outlawed studios owning theaters, effectively ending vertical integration in Hollywood.[7] This placed studios in a vulnerable position just as the glow of television screens was beginning to draw audiences away from the silver screen. By 1960, TV stations had multiplied from 98 to 440, with millions of sets sold annually, transforming living rooms into entertainment hubs. Polls revealed steep declines in movie-going—up to 30% among families with televisions—while suburban sprawl and the lure of new pastimes like sports and travel deepened the exodus from theaters.[8] By 1960, 90% of homes owned a television set.[9] In response to the staggering popularity of this new mode of in-home entertainment, film studios began licensing old movies to air on television.[10] Imperatively, they failed to pay actors for the profits made from these television deals. In response, actors went on strike to demand residuals for post-1948 films licensed to television stations.

Things happened swiftly. From the outset, stars proved eager to be involved in the demands for residual pay and contractual fairness. On the night of Feb. 17, 1960, at the home of actors Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, 100 members of the Screen Actors Guild met to authorize a strike.[11] This was a spectacle, a dramatic tableau of Hollywood’s A-list power converging in support of labor rights. Over the course of two hours and fifteen minutes, they secured the backing of more than 100 top stars, including John Wayne, Debbie Reynolds, Shirley MacLaine, Glenn Ford, and Dana Andrews.[12] Traffic snarled outside, prompting Beverly Hills police to manage the flow, while Curtis and Leigh even hired “parking boys” to tend to the fleet of luxury cars outside. “It’s our contribution to the strike fund,” Curtis quipped, adding to the evening’s mix of Hollywood glamour and gritty union resolve. Stars like Charlton Heston and James Garner lent further credibility, taking places on the negotiating committee alongside union leaders. On March 7, 1960, guild members voted to approve the motion to strike by 83%.[13] This meeting of Hollywood’s brightest was more than a labor negotiation; it was an example of star power wielded for collective gain, transforming the typically glamorous world of cinema into a battleground for workers’ rights.

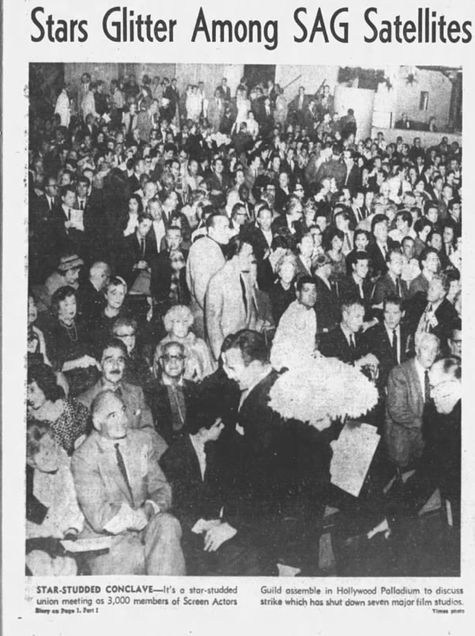

One week later, on March 13, the marquis of the Hollywood Palladium was illuminated, bold block letters spelling out: “SAG STRIKE MEETING”.[14] Close to 4,000 members of the Screen Actors Guild arrived to discuss next steps, as well as to sign a few autographs out front.[15] This impressive roster of supporters included then-president of SAG, Ronald Reagan, as well as Bette Davis, James Cagney, and John Wayne. The Los Angeles Times reported that it was “– the most star-studded union meeting in history.”[16]

Following the meeting, SAG president Ronald Reagan, alongside his wife Nancy, stood in front of a barrage of press to answer questions. After issuing a brief statement regarding the state of negotiations, Reagan added, “I heard or saw no expression of anyone who did not endorse the guild’s position overwhelmingly.”[17] Presenting as a united front, the assemblage of stars at the Palladium that night did what stars do best: attract visibility. The following day, papers ran photos of this event, emphasizing the role of stars amongst this gathering of actors.

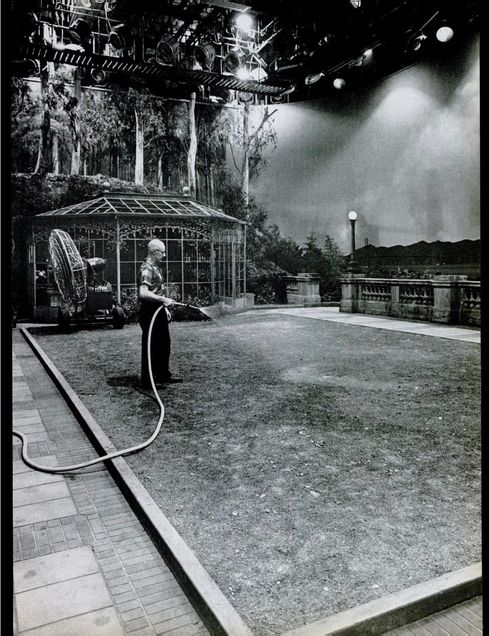

For studios, these demands were ridiculous; why should an actor be paid twice? 20th Century Fox president Spyros Skouras was quoted in Daily Variety threatening “a struggle to the death.”[18] Because of the contractual hegemony of the studio system, star participation in labor organizing was inherently disruptive. Studios felt that by acquiescing, their own power would be undermined. They did not budge. In response, SAG members conducted mass walked offs. Work on eight features — including The Wackiest Ship in the Army and Butterfield 8 — screeched to a halt. It was a frantic moment for studios, which risked losing millions of dollars should production stop altogether. At Fox, Marilyn Monroe, Yves Montand and Tony Randall walked off the set of Let’s Make Love. At Paramount, Fred Astaire, Debbie Reynolds and Lilli Palmer walked away from work on The Pleasure of His Company.[19] Whereas the 2023 SAG strike would utilize picket lines, the strike of 1960 relied on the spectacle of absence. The studio lots were, for the first time since their founding, loud with silence. In a photograph featured in LIFE Magazine, a Paramount employee waters the lawn of a vacant set.[20]

Jumping the Runway: Elizabeth Taylor and Star Apathy

Not all stars chose to worry themselves with the negotiations. For the highest paid within the Hollywood system, concerns over residuals were less pronounced. At the very least, interest in participating in negotiations or public displays of resistance was minimal. For Elizabeth Taylor, a “Star” of the highest order, the strike was merely a backdrop in her larger battle for agency within the studio system.

When the SAG strike began in 1960, Taylor was in New York, working on the set of Daniel Mann’s Butterfield 8 (1960). The film was a contractual obligation for Metro Goldwyn Mayer; it would be Taylor’s last performance for the studio before she was to be legally released from her contract to begin work on her next role, Cleopatra (1963), with 20th Century Studios.[21] Frankly, differently for many of those on strike, money was the least of Taylor’s concerns. 20th Century had offered her a record-breaking one million dollars to play Cleopatra; unlike many of her peers, Taylor was one of the most handsomely paid actresses in film.[22] Taylor’s relationship to the studios played out privately and individually, as opposed to those expressing their grievance in SAG meetings.

On the set of Butterfield 8, tensions were high. Amidst the media fallout from Taylor’s infamous marriage to Eddie Fisher, MGM capitalized on the scandal to draw attention to their film. Weaponizing Taylor’s status as fallen star and contractual employee of the studio, her studio-mandated performance as sex worker Gloria Wandrous was a cheap allegory for Taylor’s transgressions against the sanctity of marriage in the public eye, not to mention a means of selling tickets. For Taylor, exasperated with studio heads, 1960 provided a convenient moment of reprieve; the strike was an opportunity for escape. Utilizing the work stoppage to her advantage, Taylor walked off set with Fisher (also cast in Butterfield 8), and onto a plane bound for Jamaica.[23]

Her general disdain for the project and indifference to the strike are notable, but speak to the tensions that arose between stars and studios more generally. Stars lived in perpetual tension with studio contracts, which bound them strictly to the demands of profit-minded executives. While Hollywood sells a compelling vision of the leisurely actor, an artistic spirit living in utmost privilege, the contractual nature of their profession stripped the agency of actors. Studio heads arranged marriages, restricted diets, ordered abortions, and distributed pharmaceuticals to stars throughout the early half of the twentieth century.[24] Morality was literally written into these contracts via the Hays Code, legally binding the bodies and behaviors of stars on-screen.[25] Mid-century actresses recall that in this code were stipulations against pregnancy, requiring an abortion to avoid the profitability of a star decreasing. Contracts effectively operated as a biopolitical means of policing actor bodies.

Equally, Taylor’s explosive star power can be attributed to the growth of the ‘star economy’. In 1960, Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita introduced the term paparazzi to the public and shortly thereafter, Anita Ekburg attempted to ward off one such photographer with a bow and arrow.[26] The role and responsibility of stars was changing, as audiences gained new modes of surveillance through changing technologies. This shift amplified the marketability of celebrities while simultaneously reducing their personal boundaries; from the outset, these technologies worked to contain star figures and sell star images on a global scale.

As a case study, Taylor’s vacation should not be oversimplified as an insensitive dismissal to the strike and a lack of solidarity with her fellow actors. Rather, it can be interpreted as a complex negotiation of autonomy within an oppressive system. Given her outspoken political nature later in her career, this refusal to participate in activism or negotiations suggests Taylor’s own restricted agency as she finished out her contract with MGM.[27]

The Show Must Go On: End of the 1960 Strike

Despite dissent and, for some, complete indifference, star solidarity was epitomized by a public proclamation signed by some of Hollywood’s most iconic figures—Kirk Douglas, Lauren Bacall, James Cagney, Bing Crosby, Bette Davis, Joan Fontaine, Bob Hope, Edward G Robinson, and Spencer Tracy, among others—in 1960. The pro-labor ad, which stated, “This is no longer a matter of money or terms, but a question of principle,” framed the strike not as a negotiation over financial gain but as a moral imperative—a stand against an industry system that, in their view, undermined the dignity and rights of workers.[28] This declaration reflects how the stars, despite their privileged status, positioned themselves as part of a larger movement for fairness within the entertainment system. Indeed, their statement blurred the lines between economic self-interest and collective labor advocacy; by publicly aligning themselves in this way, these stars sought to lend the strike not only visibility but legitimacy. This collective statement of principle framed the strikes as not just a personal or isolated concern but as a broader ethical stand against exploitation.

Although actors may have walked off film studio lots, they did not collectively disavow show business. On April 4, 1960, the 32nd Oscars were held inside the Pantages Theater in Hollywood. Though it was not as large a crowd as the year before, stars still turned out to collect their awards and celebrate the year in film. Taylor and Fischer were in attendance, looking healthy and bronzed from the Jamaican sun.[29] At the outset, host Bob Hope quipped, “Welcome to Hollywood’s most glamorous strike meeting.” The audience erupted into laughter as Hope continued, “Gathered here tonight are the first mink-lined pickets in history.”[30]

SAG(-AFTRA) Presidents

The role of SAG-AFTRA presidents in labor negotiations holds a unique gravity. As actors themselves, presidents are shaped by the duality these individuals embody as both celebrated performers and stewards of collective worker advocacy. Their visibility as stars infused them with an authority that surpasses the conventional bounds of union leadership, transforming them into powerful figures who personify the union’s mission and the collective voice of its members. In the case of Ronald Reagan, his effectiveness as a negotiator would come to define his tenure as SAG president. As tensions with the studios escalated, union members sought his leadership to guide them through the impending struggles. His skill at navigating the political and economic terrain of Hollywood made him a trusted figure among both workers and executives.[31] The phrase “Ronald Reagan is playing his greatest part to the least applause” became widely circulated, capturing both a wry acknowledgment of his modest film career and a recognition of his strategic value in labor negotiations.[32]

Managing to get through to executives despite studio antagonism, an agreement emerged. SAG agreed to forego residual payments on films made prior to 1960, and producers agreed to pay residuals on all films made in 1960 and afterward and agreed to a payment of $2.25 million to form a pension and health plan.[33]

Dissent

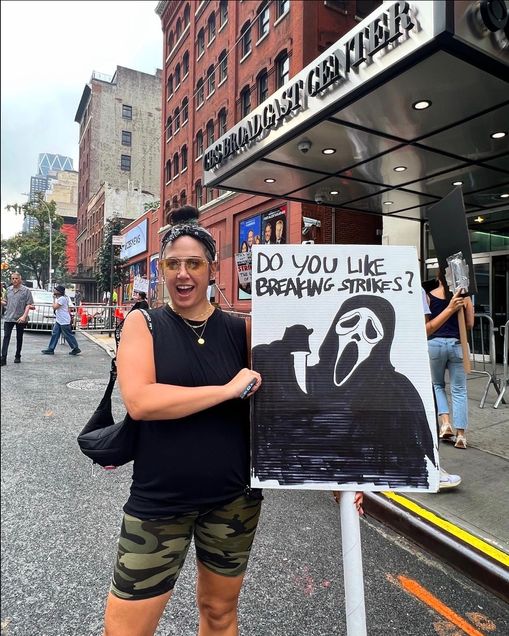

The role of star oppositionality functioned a bit differently in each respective strike. Ultimately, while several stars in 1960 openly opposed the effort to strike, the repercussions of this were minimal. In a sense, the strike operated as a discrete moment in time, with less consequence on the long-term image of these actors. Opinions were diffuse, covering a wide range of pro and anti-viewpoints regarding the negotiations. In 2023, however, backlash to those who “crossed the picket” by promoting WGA or SAG-AFTRA was far more immediate and lasting. This byproduct of a social media environment where images and ideas can be circulated at a rapid pace compared to sixty years ago was both a benefit to the movement as well as a hindrance to those who acted in opposition to the interests of SAG-AFTRA. In any case, dissent seems a natural byproduct of the class stratification in Hollywood more generally. Those with less on the line naturally have left invested in reforming the system. This is evident in the star types who chose to cross picket lines, promote studio content, or otherwise distance themselves from the movement altogether.

The 1960 strike, while fundamentally driven by demands for residuals and pension enhancements, unfolded within a notably permissive environment for internal dissent, starkly contrasting the more homogenized and tightly controlled landscape of the 2023 Hollywood strikes. Central to this dynamic was actor Glenn Ford, who articulated the ethical quandary posed by the strike’s repercussions on backlot workers, asserting, “Actors are not morally justified in striking and causing backlot workers to be laid off.” Ford’s position, representing a faction of approximately forty dissident actors, underscored a nuanced understanding of the interdependencies within the Hollywood labor ecosystem. This stance was vehemently countered by pro-strike advocates such as Tony Curtis, whose retort, “If Glenn Ford feels our union didn’t do a good job, let him join the butchers’ union,” epitomized the tension between broader labor solidarity and the specific exigencies of the actors’ union.[34] Even after the strike’s conclusion, divergences in opinion continued to emerge. The strike was over, but some actors were furious with the deal. Mickey Rooney, Glenn Ford, and Bob Hope believed SAG could have gained retroactive residuals for all films if Reagan had been tougher and held out longer. They felt Reagan and the SAG board had “screwed” them and derided the compromise as “the great giveaway.”[35]

Importantly, the 1960 strike’s relative openness to such divergent viewpoints can be partly attributed to the actors’ diminished exposure to existential threats like those faced by actors who participated in the 2023 strikes, such as artificial intelligence and pervasive inflation, which have since heightened the stakes and necessitated a more unified front in contemporary labor struggles. In an era unburdened by fears of automation rendering their craft obsolete or by economic pressures eroding their financial stability, actors were afforded the latitude to engage in pluralistic discourse and self-critique without jeopardizing the collective bargaining power of the union. This historical moment, characterized by its allowance for both collective advocacy and internal dissent, reflects a labor movement that could accommodate a spectrum of perspectives, thereby enriching the union’s strategic and ethical deliberations—an adaptability that appears constrained in the high-stakes, solidarity-driven context of the 2023 strikes.

Eventually, Reagan stepped down from his role as SAG President to pursue production.[36] Yet, his legacy within the union remained profound, with his work as president continuing to shape the guild’s trajectory. Reagan’s tenure was instrumental in positioning SAG as a powerful force within the industry, but this was not the end of his association with labor. Almost two decades later, when Reagan ascended to the presidency of the United States, he famously adopted an anti-union stance, directly opposing many of the labor movements he once helped lead.[37] In this way, Reagan’s dual legacy emerges as both a defender of labor rights in his earlier years and a staunch opponent of unions in his later political career. While his presidency was marked by actions that undermined labor unions, his time as SAG president was frequently invoked to bolster his political image, positioning him as a pragmatic leader capable of balancing the interests of powerful constituencies. This complex juxtaposition of labor advocacy and political conservatism underscores the significant transformation in Reagan’s political identity, illustrating how he skillfully used his SAG experience to defend his negotiation prowess while distancing himself from the very unions he once championed. In the years following Reagan’s departure from the Screen Actors Guild, the political landscape of Hollywood continued to evolve, shaping the role of the actors’ union as both an advocate for labor rights and an emblem of larger cultural shifts. The gradual shift from Reagan’s brand of union advocacy to the fierce and overtly political stance embodied by later leaders, like Fran Drescher, underscores a broader evolution. Hollywood unions were no longer focused solely on securing fair wages or benefits but were increasingly vocal about challenging systemic inequities within both the industry and society at large. This evolution in labor politics set the stage for the complex dynamics of the 2023 Hollywood strikes, where actors and writers once again confronted industry power and inequality.

The 2023 SAG-AFTRA Strike

In 2023, the entertainment landscape, though transformed, presented challenges all too familiar. Since the rise of streaming giants like Netflix and Hulu in the 2000s, these platforms had, for better or worse, fundamentally reshaped the industry. Recognizing the immense profits flowing through this new media ecosystem, actors demanded fairer compensation. In response, SAG-AFTRA members went on strike, risking their livelihoods to secure a contract that addressed the economic and technological shifts redefining the field.[38] Their demands signaled an urgent need to recalibrate industry standards to align with the evolving media landscape. At the heart of this conflict was the deepening rift between labor and the industry’s dominant corporations. The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP)—a powerful trade association that includes Disney, Netflix, Paramount, Warner Bros. Discovery, and NBCUniversal—was SAG-AFTRA’s adversary in its push for fairer contractual terms. From picket lines in front of major Hollywood studios, SAG-AFTRA members formed picket lines and cried out for worker protections and adequate compensation.

On the day that the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike was announced, President Fran Drescher (elected in 2021) and Chief Negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland stepped up to a podium to speak to the press. Following four weeks of exhaustive negotiations, both expressed their exasperation with studios, who (similarly to 1960) proved entirely unsympathetic to actor demands. Executives making seven-figure salaries told actors that their demands for a living wage were absurd. For reference, in 2023, a meager 7% of SAG-AFTRA actors and performers earned more than $80,000 a year, and only 14% made at least the $26,470 necessary to qualify for health insurance.[39] Insurance and residuals were not the only issues at stake, however. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, actors had increasingly been expected to film tapes of auditions at home. Because of the unequal distribution of wealth amongst actors, those with the money to spend on personal film crews gained an unfair edge. While AMPTP did offer to provide “guidelines” for the self-tapes, the guidelines would not be enforced, meaning that there would be no concrete way to ensure disparities were equalized.

Whereas stars in 1960 fought for the right to residuals, 2023’s scope was broader . At the heart of these contemporary tensions was a concern for the agency of performers within a rapidly-advancing entertainment landscape. In effect, 2023 was a battle for the futurity of entertainment and the right of artists to earn a living from their work. From the outset, this strike was a battle for autonomy within an increasingly mechanized Hollywood landscape. Much of this contested technological terrain was discussed, naturally, online. In this sense, the role of social media is an implicit part of the larger technological underpinnings of the SAG strike.

Fran Drescher: Redefinitions of Image and Power

At the forefront of this movement was SAG-AFTRA president Fran Drescher, whose leadership proved instrumental in galvanizing the strikers’ resolve. Known not only for her iconic role as the creator and star of The Nanny (CBS, 1993-1999), Drescher quickly emerged as a fierce advocate for the rights of entertainment workers, leveraging her platform and voice to challenge corporate giants and advocate for change. Elected president in 2021, Drescher was outspoken in her contempt for studio exploitation.[40] In a spirited press conference announcing SAG-AFTRA’s vote to go on strike, she denounced intemperate executives and linked the struggle of actors to global labor movements. From behind a podium, Drescher stated emphatically, “We are being victimized by a very greedy entity…It is disgusting. Shame on [the studios]. They stand on the wrong side of history, at this very moment.”[41] Drescher went on to deliver a searing condemnation of not only the studio system, but capitalism as a whole. At one point, she looked into the crowd and said solemnly, “Most Americans don’t have more than five hundred dollars saved. That weighs on us heavily.”[42] By associating the struggle of working-class Americans with those in Hollywood, Drescher attempted to connect the plight of actors to broader economic anxieties. In other words, while Hollywood may work to sell a vision of opulent leisure, there are many workers struggling to pay bills and feed their families. The discursive work of her statement sought to ensure that actors and writers are viewed as a class of worker victimized by corporate greed. Her unwavering stance underscored the urgency of the strike and amplified the call for reform as the industry faced a pivotal moment in its ongoing evolution.

Drescher’s ascendancy to impassioned strike leader was reported as “unlikely,” as members of SAG-AFTRA openly questioned her lack of experience.[43] While there are clear hegemonic implications to the undermining of a Jewish woman in a position of leadership, critics cited potential conflicts of interest. In 2023, when negotiations to avoid a strike were in full swing, Drescher appeared in photos with fellow celebrity Kim Kardashian at a dinner for the designer brand Dolce and Gabbana in Italy.[44] Needless to say, the optics undermined her public denunciation of corporate greed and wealth.

Despite critical industry voices, Drescher possessed a decidedly political edge. A survivor of uterine cancer, Drescher began a nonprofit called “Cancer Shmancer,” which works to call out the medical industrial complex and promote healthy living; notably, the website invokes the Fredrick Douglass quote “’Power concedes nothing without demand. It never has and it never will” as a means of underscoring its ethical mission.[45] In a 2017 interview, Drescher went so far as to publicly label herself “anti-capitalist.”.[46] Many felt that her leadership represented a brave new front, a form of star power unafraid to embrace unions and decry corporate greed.

Drescher’s political engagement parallels the shifting landscape of public discourse in the entertainment industry, particularly regarding labor strikes. In the 1960 strike, for example, opposition to the movement was met with relatively few consequences, as the variety of opinions held by actors remained largely compartmentalized. However, in the 2023 strike, the rapid spread of opinions through social media meant that those who opposed the strike faced more enduring backlash, underscoring the way in which public figures, like Drescher, are now more susceptible to the immediate and lasting impact of their political stances. In both cases, the tension between opposition and solidarity reflects a broader social and political evolution in how power dynamics are negotiated and contested.

‘Scabbing’ in the Age of Techno-Surveillance: Kim Kardashian and Selena Gomez

For stars with a larger platform, “mega-stars,” who possess vast access to social and financial capital in the age of social media, there are literally millions of eyes on them. While social media offers a level of direct communicative agency not afforded to stars of a more classical era, these online spaces often act as forums of opposition, as the simulacrum of the star is transformed into a meta-textual site of cultural discourse. In the case of two such megastars, Selena Gomez and Kim Kardashian, their social media promotion of shows they were acting in during the strike prompted retaliatory backlash from fans and entertainers alike. From the beginning of the strike, SAG-AFTRA called on members to cease promotions for any contracted labor. With a combined Instagram following of 782 million followers, Gomez and Kardashian’s virtual picket crossings were witnessed on a global scale, intensifying the impact and outrage that followed.

In June of 2023, Kim Kardashian took to social media platform X (formerly Twitter) to engage with fans. Kardashian posted, “Hi guys! I’m on set of AHS and we have some time between shots. What are you all up to????”[47] This “check-in” is not an uncommon occurrence amongst stars in the digital age, many of whom speak with fans to better cultivate the parasocial attachment that ensures their social capital. However, considering SAG-AFTRA strike rules against promotional material, Kardashian’s post was immediately condemned. Her explicit promotion of American Horror Story, one of only a handful of shows to resume filming during the strike, further underscored her complete inattention to the larger historical moment.[48] A response from comedian Joel Kim Booster summed up the general feeling concisely. Booster replied to her question with, “Picketing, Kim.”[49] Another said, “Sitting at home since no work due to strike. Why is AHS still filming. Show solidarity with our brother and sisters in the WGA.”[50] Kardashian did not acknowledge the public backlash, nor the response from Booster, and instead went on to answer questions from supportive fans. To her initial question, she received 2,800 replies. It is worth noting that as a star persona, while not known for her acting, Kardashian is a multimillionaire and multi-hyphenate, her class positionality rendering her both glamorous but out of touch, and prototypically bourgeois. Whereas Elizabeth Taylor was free to fly to Jamaica without much of an uproar, 2023 audiences are far more hostile to Kardashian’s seeming ignorance due to the availability of information as well as her unique embodiment of material wealth.

Similarly, actress and pop musician Selena Gomez was lambasted for posting promotions for her show Only Murders in the Building in August 2023.[51] Gomez is a lifelong entertainer and, more recently, the founder of “Rare” Makeup; as of 2024, Rare is valued at over 2 billion dollars.[52] Gomez is also known for her mental health advocacy and work as a UNICEF ambassador. Differently from Kardashian, Gomez is a seasoned actress, beginning her career as a child actor on Disney Channel. Months into the strike, fans struggled to understand how Gomez could so blithely ignore the demands of SAG-AFTRA, given her extensive history in the industry.

That said, Gomez, similarly to Kardashian, resides in a stratosphere of wealth fundamentally incomprehensible to most, demonstrating the wide gap between those for whom the strike represented a real but necessary hardship and those fully insulated by their own privilege.[53] Though the post was deleted in the wake of controversy, in the 15 hours it was available it generated over 1.1 million “likes.” [54] Considering the 2023 response to these stars and their defiance of SAG-AFTRA strike protocol, it becomes increasingly clear that stardom in the contemporary era operates as an embodiment of cultural power struggles, as a site for audiences to play out their rage with larger systems.

Conversations around privilege and celebrity have taken on a different, more critical tone in recent years. Recalling the infamous New York Mag “nepo baby” cover of celebrity children of famous parents that was published in January 2023, cultural conversations concerning hegemony and power in Hollywood were already rampant before the strike ever got underway.[55] Audiences were frustrated with a star system they viewed as regurgitated, and a cultural system that prioritized the interests of the already-famous. This was emblematized by Drew Barrymore, heiress to one of America’s most famous entertainment families and, as of 2023, an infamous Hollywood scab.[56]

In 2023, Barrymore was the host of daytime talk show The Drew Barrymore Show. As a persona, Barrymore made a name for herself as a feel-good survivor of addiction and childhood fame. As a host, she offered a safe space for guests through displays of hand holding, sitting closely beside those she’s interviewing, and her “down to earth” way of approaching subjects. Audiences liked Barrymore— until she made the decision to resume filming her show despite the ongoing WGA strike. While talk shows technically operate under different contractual agreements, and Barrymore’s filming did not violate that, the WGA writers working on the show would be effectively forced to cross the picket in order to keep their jobs writing for the show.[57] These already precariously-conflicted labor interests were compounded by the fact that Barrymore faced legal action from Paramount should she stop filming. Obviously, the role of writers to a talk show is indispensable, and reporters wondered aloud whether Barrymore would write the show herself. When reports circulated about Barrymore banning WGA merchandise on set, things took on a more suppressive tone.[58] While Barrymore had initially championed the strike, she was now faced with the difficult decision to go on air without writers or stay dark and risk legal action and the firing of the employees she allegedly wanted to protect.

It was not simply her contractual return to production that soured public perception, but rather the flawed rhetoric surrounding her decision. Her Instagram statement, intended as a gesture of openness, instead exemplified the perils of celebrity figures “breaking the fourth wall” to address audiences directly. In her post, Barrymore defended her choice to resume filming: “I am making the choice to come back for the first time in this strike for our show, that may have my name on it, but this is bigger than just me.”[59] She portrayed the decision as a commitment to maintaining the show’s role as a mirror to “sensitive times,” claiming adherence to strike rules by avoiding promotion of struck work. The Writers Guild of America (WGA), however, swiftly corrected this claim, noting that her show remained a “WGA-covered, struck show” and announcing plans to picket its production.[60] Barrymore’s choice invited a re-examination of her carefully curated public persona: a shift from the image of empathy and solidarity she had cultivated, seen when she stepped down as MTV Movie Awards host in support of the strike, to one now perceived as prioritizing self-interest and corporate alliances over labor solidarity.

This pivot highlights the fragility of celebrity as “cultural merchandise,” showing how swiftly public perception can recalibrate when stars engage, or conspicuously fail to engage, in labor conflicts. The National Book Foundation’s decision to withdraw Barrymore’s invitation to host the 74th Annual Book Awards Show crystallized her image’s transformation—from a figure of warmth and candor to one viewed as complicit in corporate agendas.[61] Barrymore’s case underscores the delicate balance that stars must maintain between industry obligations, personal brand, and the ever-shifting expectations of the public within Hollywood’s intricate hierarchies of power and labor.

Conclusion

The materiality of stars functions as a site of dynamic tension, a site where unresolved contradictions continually unfold. These contradictions are not mere anomalies but are structural forces that operate across various social strata: the distinction between artists and agents, actors and workers, the 1% and the broader working populace. Within this frame, the labor resistance manifested in the 1960 and 2023 strikes serves as a critical expression of privileged labor, underscoring the inherent complexities of this category. As Richard Dyer provocatively argues, stars transcend the status of mere entertainers, emerging instead as cultural symbols that “articulate what it is to be a human being in contemporary society.”[62] From this vantage, stars are not static commodities but are inextricably bound to the cultural and ideological tensions of their era, serving as crucial signifiers of shifting power dynamics and societal values.

Thus, stardom emerges as a multifaceted embodiment of the broader cultural power struggles that define the contemporary moment. It operates as a site where the spectator’s complex emotional and ideological investments—ranging from admiration to resentment, identification to alienation—are projected onto figures who simultaneously reflect and contest the normative structures of power. Stars, in their negotiation of visibility and vulnerability, become symbolic arenas in which the public performs and processes its engagement with larger socio-political forces, often offering a mediated space to confront the contradictions of capitalist structures, labor relations, and collective agency.

The 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike serves as a poignant manifestation of this tension, illustrating how stardom intersects with labor in the context of the entertainment industry’s systemic inequalities. In this instance, stars, through their privileged positions, became central agents in the fight for equitable compensation, labor protections, and creative autonomy. However, in doing so, they simultaneously embodied the contradictions of their status as both highly visible cultural icons and members of a labor force whose struggles are often obscured by the commodification of their image. The 2023 strike thus serves as a crystallizing moment where the intersection of cultural power, economic inequality, and labor resistance is made visible, revealing that stars, in their brilliance and contradictions, remain integral to the ideological terrain on which contemporary power struggles are fought and reflected.

[1] Hortense Powdermaker, Hollywood: The Dream Factory (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1950).

[2] Richard Dyer and Paul McDonald, Stars (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019).

[3] Edgar Morin, The stars: An Account of the Star-System in Motion Pictures. Grove Press| John Calder, 1960.

[4] Ibid.149.

[5] Murray Ross, Stars and Strikes: Unionization of Hollywood. Columbia University Press, 1941. 1.

[6] Dyer, Stars. 154.

[7] Peter Lev, Transforming the Screen, 1950-1959, vol. 7 (Univ of California Press, 2003). 2.

[8] Ibid. 9.

[9] Laura Jenemann, “Research Guides: American Women: Resources from the Moving Image Collections: Television,” research guide, Library of Congress, accessed December 1, 2024, https://guides.loc.gov/american-women-moving-image/television.

[10] For more on the complicated process of licensing Hollywood films on early television, see: Jennifer Porst, Broadcasting Hollywood: The Struggle over Feature Films on Early TV (Rutgers University Press, 2023).

[11] “Tea, Crumpets, and Strike Talk: Curtis-Leigh Open Their House to 50 Actors and Invite SAG to Give Low Down on Facts,” Daily Variety, February 11, 1960.

[12] Cynthia Littleton. “The SAG-WGA Double Strike of 1960: How Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Ronald Reagan, Desi Arnaz and More Guided Hollywood Back to Work.” Variety (blog), July 17, 2023. https://variety.com/2023/biz/news/sag-strike-1960-wga-janet-leigh-tony-curtis-ronald-reagan-1235672266/

[13] SAG-AFTRA. “History of Residuals.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.sagaftra.org/membership-benefits/residuals/history-residuals.

[14] “USA: HOLLYWOOD: FILM STARS ATTEND STRIKE MEETING,” British Pathé, accessed November 10, 2024, https://www.britishpathe.com/asset/114912/.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Actors Strike Meeting Draws Roster of Stars,” Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1960, p. 2, accessed November 10, 2024, https://latimes.newspapers.com/image/381002967/.

[17] “USA: HOLLYWOOD: FILM STARS ATTEND STRIKE MEETING,” 1:10.

[18] Vincent Canby, “Skouras Fears Strike Battle ‘To the Death,’” Daily Variety, December 30, 1959.

[19] “Hollywood: Strike in a Ghost Town.” TIME, March 21, 1960. https://time.com/archive/6829812/hollywood-strike-in-a-ghost-town/.

[20] “Strike Long Job,” LIFE, March 21, 1960, 25.

[21] Ellis Cashmore, Elizabeth Taylor: A Private Life for Public Consumption (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 54.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Valley Times (North Hollywood, CA), March 16, 1960, 15.

[24] EJ Fleming, The Fixers: Eddie Mannix, Howard Strickling and the MGM Publicity Machine (McFarland, 2015).

[25] Sheri Chinen Biesen, Film Censorship: Regulating America’s Screen (Columbia University Press, 2018).

[26] Cashmore. 5.

[27] Kate Andersen Brower, Elizabeth Taylor: The Grit and Glamour of an Icon (New York: Harper, 2022).

[28] “HOLLYWOOD: Strike in a Ghost Town”.

[29] Taylor was nominated for best actress for her role in Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). She lost to Simone Signoret for Room at the Top. She would, however, win in 1961 for her performance of Gloria Wandrous in Butterfield 8 (1960). The 32nd Academy Awards 1960, October 5, 2014. https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1960.

[30] The Opening of the Academy Awards: 1960 Oscars, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QvbC8tQvTF0.

[31] Lou Cannon, Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power (Public Affairs, 2003).

[32] Thomas Doherty, “1960 SAG-WGA Strike: Reagan, Heston and How Hollywood Made a Deal,” The Hollywood Reporter, July 18, 2023.

[33] “History of Residuals,” SAG-AFTRA, accessed November 2, 2024, https://www.sagaftra.org/membership-benefits/residuals/history-residuals.

[34] Doherty, 1960 SAG-WGA Strike.

[35] Dan E Moldea, Dark Victory: Ronald Reagan, MCA, and the Mob, vol. 23 (Open Road Media, 2017). 17.

[36] “Liz and Eddie Arrive for Academy Fete,” The Los Angeles Times, April 1, 1960, 51.

[37] Henry S Farber and Bruce Western, “Ronald Reagan and the Politics of Declining Union Organization,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 40, no. 3 (2002): 385–401.

[38] Previously referred to as SAG, SAG-AFTRA Formed in 2012 from the merger of the Screen Actors Guild and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, SAG-AFTRA represented around 160,000 industry professionals in 2023. These members ranged from celebrated Oscar-winning actors like Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep to radio hosts and television presenters.

[39] Kalia Richardson. “Most SAG Actors Don’t Even Make a Living Wage. Here Are Their Stories,” Rolling Stone, accessed October 28, 2024, https://www.rollingstone.com/tv-movies/tv-movie-features/actors-strike-hollywood-sag-aftra-living-wage-healthcare-struggle-1234798347/

[40] “SAG-AFTRA Members Elect Fran Drescher President of the Union and Joely Fisher as Secretary-Treasurer,” SAG-AFTRA, accessed Nov. 1, 2024, https://www.sagaftra.org/sag-aftra-members-elect-fran-drescher-president-union-and-joely-fisher-secretary-treasurer.

[41] CBS News. “Fran Drescher Delivers Fiery Speech on SAG-AFTRA Strike”, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4SAPOX7R5M.

[42] Fran Drescher, “Fran Drescher Delivers Fiery Speech on SAG-AFTRA Strike,” CBS News, July 13, 2023, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4SAPOX7R5M.

[43] Joy Press, “A Leader Rises: ‘Just Watched Fran Drescher Chew the #AMPTP’s Face Off,’” Vanity Fair, July 14, 2023. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2023/07/a-labor-leader-rises-just-watched-fran-drescher-chew-the-amptps-face-off.

[44] Chris Gardner, “SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher Criticized for Dolce & Gabbana Outing in Italy Amid Contract Negotiations: ‘It’s Bad Optics,’” The Hollywood Reporter (blog), July 11, 2023. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/fran-drescher-kim-kardashian-dolce-and-gabbana-event-italy-sag-negotiations-1235532562/.

[45] Cancer Schmancer, “Cancer Schmancer,” accessed November 10, 2024, https://www.cancerschmancer.org/press/momentum-women-may-2008.

[46] Peter Moskowitz, “How to Be More Fabulously Radical in 2017, According to Fran Drescher,” Vulture, June 8, 2017, https://www.vulture.com/2017/06/fran-drescher-how-to-be-more-fabulously-radical-in-2017.html.

[47] Kardashian has since deleted the post: Alexis Soloski, “In ‘American Horror Story,’ Kim Kardashian Skims the Surface,” The New York Times, September 21, 2023, sec. Arts.

[48] Notably, Kardashian’s posts were treated as an extension of American Horror Story producer Ryan Murphy’s animosity towards the strike. At the time, reports stated that those working under Murphy were scared to speak out about the strike due to fears of blacklisting. Murphy’s power as a prolific producer and showrunner is a testament to the multi-layered hegemonic struggles constantly playing out in Hollywood. Star Studies demands an industrial and power-based assessment of an actor’s positionality. In Kardashian’s case, her dual role as multimillionaire and actress on Murphy’s show compound in the larger discursive environment of her attitude toward the strike.

[49] Booster has deleted the response. Ibid.

[50] Kirk Kelly [@KirkKelly], “@KimKardashian Sitting at Home since No Work Due to Strike. Why Is AHS Still Filming. Show Solidarity with Our Brother and Sisters in the Wga,” Tweet, Twitter, June 23, 2023. https://x.com/KirkKelly/status/1672344083275153409.

[51] Zack Sharf, “Selena Gomez Breaks SAG Strike Rules? ‘Only Murders’ Post Ignites Backlash,” Variety, 2024, https://variety.com/2023/tv/news/selena-gomez-breaks-sag-strike-rules-only-murders-post-backlash-1235708385/.

[52]Bloomberg.com, “Selena Gomez Weighs Sale of Cosmetics Brand Valued at $2 Billion,” March 18, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-03-18/selena-gomez-weighs-sale-of-cosmetics-brand-valued-at-2-billion.

[53] “Selena Gomez Is a Billionaire Thanks to Her Beauty Brand,” Bloomberg, September 6, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-09-06/selena-gomez-is-a-billionaire-after-rare-beauty-success-exclusive.

[54] Sharf, Variety.

[55] Priyanka Mantha, “Extremely Overanalyzing Hollywood’s Nepo-Baby Boom,” New York Press Room, December 19, 2022, https://nymag.com/press/2022/12/extremely-overanalyzing-hollywoods-nepo-baby-boom.html.

[56] Carol Stein Hoffman, The Barrymore’s: Hollywood’s First Family (University Press of Kentucky, 2001).

[57]Josef Adalian and Kathryn VanArendonk, “The Backlash Came for Drew Barrymore,” Vulture, September 14, 2023.

[58] cass [@goldenilomilo], “Literally Just Got Kicked out of the Drew Barrymore Show Bc We Were Handed Pins from the Writers’ Strike. We Offered to Put Them Away and Some Bald Bozo Said We Weren’t Allowed in Sooo We Joined the Strike! #wgastrong #DrewTheRightThing @DrewBarrymore,” Tweet, Twitter, September 11, 2023. https://x.com/goldenilomilo/status/1701240438290518298.

[59] Alex Abad-Santos, “Drew Barrymore Tried to Live, Laugh, Scab Her Way across the Picket Line. It Didn’t Work,” Vox, September 19, 2023, https://www.vox.com/culture/2023/9/19/23880858/drew-barrymore-show-writers-strike-backlash-apology.

[60] Ibid.

[61] National Book Foundation [@nationalbook], “An Update on the Host of the 2023 National Book Awards. Https://T.Co/aa5aLh0FIU,” Tweet, Twitter, September 12, 2023. https://x.com/nationalbook/status/1701718719745978601.

[62] Richard Dyer, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society (London: British Film Institute, 1986), 7.