Anne Callahan

Anne Callahan is a PhD student in American Studies at Boston University studying representations of work and free time in 19th and early 20th century North American media, with particular attention in the opportunistic use of working hours for play, invention, and personal profit, and the creation and theorization of alternatives to managerial workplaces.

Noise and Work in Nineteenth-Century Lowell, Massachusetts: Stone Blasting, Shouts and Hissing, and Ringing in My Ears

Noise characterized the experience of work in nineteenth-century Lowell, Massachusetts. Plotted into existence by Boston investors eager to create a model industrial city, Lowell was under construction even before the town was incorporated in 1826.[1] By the 1840s, visitors to Lowell marveled at the “jar and whirl of these crowded and noisy mills,” the inescapable “noise of hammers, of spindles,” and the “terrific … thumpings” of the water wheel.[2] Yankee women who moved from rural New England for jobs as “operatives” – workers who operated industrial machinery – wrote and received letters about the “noisey factory” and the “din and clatter of machinery.”[3] They dramatized the “strange discord,” the “click-clack” of the shuttles, and “the whizzing and singing” of spinning machines in published stories and poems.[4] Factory bells sounded as many as six times a day, prompting one operative to parody the “ding dong of a bell.”[5] Workers went home to a “noisy tenement,” celebrated the Fourth of July with cannon fire, and summoned the police to quiet disturbers of the peace.[6]

Nineteenth-century Americans told stories about noise in part to make sense of transformations in familiar environments and economic, social, and political relations. The image of the quiet country village transformed into the noisy manufacturing city pervaded newspaper and magazine stories in the second half of the nineteenth century. Depending on the context, this flexible rhetorical device could portend moral corruption, trigger colonial nostalgia, or demonstrate U.S. ingenuity and cosmopolitanism to audiences abroad. “The hum of industry is now heard where a year ago all was silent as the tomb,” cheered the metalworkers’ trade magazine The Iron Age in 1890, echoing earlier settler narratives that justified land expropriation as the improvement of “vacant soyle” and “barren wilderness” through agriculture.[7] Industrial development elicited laments as well as cheers. A poem published in a textile trade magazine in 1896 bemoaned that “the factory whistle roar / And screeching scream” had replaced “Nature’s joyous harmony.”[8] The language nineteenth-century Americans used to describe their “heard world” suggested prosperity and sociability as well as terror and loss of control.[9]

In this essay I examine three accounts of noises that interfered with – “drowned” or “put down” – other sounds in Lowell in the period from 1835 to 1846. Following sound studies scholar Mark M. Smith, I use “sound” as a generic term for any element of the “heard world,” and define “noise” as “gratuitous” sound – sound that some hearers, at least, deemed loud, noxious, inescapable, or alienating.[10] I relate each description of noisy interference to the work culture emerging in this period, as cotton mill investors struggled to maintain the mills’ famously high dividends and preserve Lowell’s reputation as a model manufacturing city while facing unpredictable markets.[11] Narrowly focusing on accounts of noise that interfered with other sounds has the advantage of showing interconnected layers of sounds – and by extension events and experiences – that characterized work life in Lowell. Descriptions of noisy interferences also reveal hierarchies assumed by the people who documented them. Which sounds deserved hearing and which sounds counted as ‘noise’ depended on the hearer.

Published and manuscript sources documenting work life in nineteenth-century Lowell are full of references to noise. Historian David Zonderman has drawn from these sources to discuss Lowell operatives’ aural experiences of two industrial machines for producing cotton cloth, the spinning throstle and the power loom.[12] Mark M. Smith has analyzed mill operatives’ descriptions of sounds in Lowell in order to trace female mill operatives’ engagement with popular ideas about natural versus man-made worlds, and to complicate critic Leo Marx’s metaphor of the “machine in the garden.”[13] In his longer study Listening to Nineteenth-Century America, Smith demonstrates how Northerners and Southerners in the U.S. attached meanings to sounds that reflected regionally-grounded notions of progress and degradation.[14] This essay examines accounts of noisy interference in order to gain insight into New Englanders’ experiences as they negotiated first the emergence, then the increasing dominance, of industrial work society.

In her feminist critique of work politics, The Problem with Work, critic Kathi Weeks introduces the concepts of the “work society” and “work values” in order to emphasize the public and political, rather than private and inevitable, nature of waged work. For Weeks, “work values” assume that waged work, rather than other activities, is the natural mechanism for acquiring basic needs – food, clothing, shelter – as well as healthcare, care during old age, social relationships, and social status. Collective acceptance of “work values” then produces “work society.”[15] Weeks’s aim is to show that the work society many of us in the U.S. today take for granted is constructed and contingent; other kinds of societies built on other values are possible. Many New Englanders in the first half of the nineteenth century shared Weeks’s suspicion of waged work as a god-given good, and their responses to the work society taking hold around them – in particular, to the emergence of an exclusive and seemingly permanent class of owner-employers – ranged from curiosity to confusion, from satisfaction to fury. I read the accounts of noisy interferences that follow as evidence of New Englanders’ motivations and compromises as they responded to changing meanings of work.

“hissing and shouts”

“Look at Lowell! See an anti-abolition meeting put down by hissing and shouts!” The Washington, DC-based newspaper the Extra Globe reprinted this account of noisy disruption from the United States Telegraph in September 1835.[16] Other newspapers picked up the story of Lowell citizens ‘hissing down’ an anti-abolition meeting. The Baltimore-based Niles’ Weekly Register reprinted stories from newspapers in Virginia and South Carolina that recommended boycotting Lowell cloth in response to the “outrageous conduct at an anti-abolition meeting” and Lowell’s “hostility” to the South. Writers for the Extra Globe and the New York American downplayed the story. “No anti-abolition meeting was put down there by ‘hissing and shouts,’” the Extra Globe editor assured their readers, “but one was held there and largely attended, and resolutions hostile to the proceedings of the abolition fanatics passed unanimously.” The New York American’s commentary, reprinted in the Niles’ Weekly Register, dismissed the original source of the report, the Lowell Times, as a “rank abolition paper, as bad almost as the Liberator itself.”[17]

The surge of national interest in Lowell’s abolition politics in the fall of 1835 reflected Lowell’s prominent position in public discourse, as a model industrial city on an international stage and a nexus that linked together Northern and Southern settler economies as the two-part foundation of the fabulously profitable global cotton trade. “Lowell is not an obscure and insignificant village, but an extensive manufacturing town,” wrote The Richmond Compiler, expressing alarm that abolitionists had “made such progress” there.[18] Indeed, Lowell’s reach extended far beyond New England through a network of economic relations that produced wealth for cotton mill investors, plantation owners, and middle agents in the U.S. and England, while calling for faster work and greater output from enslaved Black farm laborers who farmed cotton fields and from waged factory operatives who produced cotton cloth.[19] Antislavery protestors’ alleged “hissing and shouts” in Lowell portended danger and instability from the perspective of newspaper editors in Washington, D.C., Charleston, and Richmond aligned with plantation owners, and with that of Northerners invested in avoiding sectional confrontation at any cost. To self-declared abolitionists and other resisters who read or heard about the Lowell anti-abolition meeting, the “hissing and shouts” may have been welcome news that proved the irrepressibility of antislavery sentiment.

The flurry of commentary about the Lowell anti-abolition meeting in newspapers far from Lowell also reflected a national preoccupation with assigning places and people to one or another side in the slavery debates that absorbed U.S. culture in the 1830s and 1840s. Individuals identified themselves and others, as well as churches, newspapers, towns, and cities, as “anti-slavery,” “emancipationist,” “gradualist,” “immediatist,” “nonextensionist,” “amalgamationist,” “colonizationist,” “abolitionist,” and “anti-abolitionist.”[20] Motivated by white Southerners’ outrage following the July 1835 abolitionist postal campaign, in which members of the newly-formed American Anti-Slavery Society mailed thousands of abolitionist books and newspapers to politicians and clergymen all over the U.S., Yankee men with political and financial investments in the South rushed to organize anti-abolition meetings and articulate statements of solidarity with “Southern brethren.”[21] Anti-abolition leaders presented their position as a reasonable middle ground that accommodated both pro-Southern-rights and antislavery beliefs while denouncing “incendiary” abolitionists. Stopping abolitionists became a rallying cry for white mobs throughout the U.S., who led violent multiple-day attacks on Black neighborhoods in Philadelphia, New York City, and Cincinnati in 1834 and 1836; surrounded a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and dragged abolitionist figurehead William Lloyd Garrison through the streets in 1835; and murdered abolitionist printer Elijah Lovejoy in Alton, Illinois in 1837.

Two local newspapers offered details about the 1835 Lowell anti-abolition meeting allegedly disrupted by “hissing and shouts.” The antislavery Lowell Journal and Mercury published a transcript of the meeting that included an assertion of Southern states’ constitutional right to retain “regulation and control of slavery” and a resolution to “cherish the Union and maintain inviolate the compact under which it was formed.” The meeting organizers reserved their strongest language for condemning “Anti-Slavery societies of the North” who called for “immediate abolition” using tactics “tending to endanger the harmony of the Union, to excite sectional jealousy and ill will, to disturb the domestic relations of society, and leading to insurrection and civil war.”[22] The report in the antislavery Lowell Times, reprinted in Niles’ Weekly Register, denounced the anti-abolition meeting as “utterly subversive to the principles of the constitution, and of common-sense” and described the “hissing, scrapings, coughs, and yells” and “disorder and confusion” that resulted in the postponement of the meeting until the following week. The Lowell Times writer chose an example of religious hypocrisy for their rhetorical climax. When “an attempt was made by H. C. Meriam, esq. to justify slavery from the scriptures … the strongest disapprobation was manifested by the audience, who, after repeated but ineffectual calls to order, hissed him down.” [23]

Descriptions of audiences who “hissed down” actors and speakers appeared in publications in the U.S. and Europe throughout the 1800s. According to a Boston theater critic, hissing was acceptable behavior at the theater and offered useful feedback: “… what the public hiss down in the performance of actors the actors will not attempt, nor will the managers ‘bill’ it, for the next performance.”[24] But to hiss down a political speech was not “recognized as the dignified or legitimate way of shewing disagreement,” according to an article reprinted in the Boston magazine Littell’s Living Age.[25] Another magazine writer distinguished hissing from other expressions of disapproval as “far too direct and personal.”[26] The intended effect of hissing was to render public speech indecipherable, but hissing also had an association with the devil that distinguished it from shouting, coughing, or stomping. In an 1852 U.S. dictionary, “to hiss down” is one definition of “to damn,” alongside “to curse; condemn,” while “hiss” by itself was defined as “the cry of a serpent; expression of contempt.”[27] Many Northerners, including abolitionists, cautious antislavery advocates, and others who rankled at “slave power” if not slavery itself, found common ground in their abhorrence of biblical arguments to justify slavery. From their perspective, hissing may have seemed like the ideal response. For the same reason, those on the receiving end of a hiss may have taken special offense.

For residents of Lowell, news about the noisy disruption of the anti-abolition meeting would have called to mind another meeting disrupted by hissing and shouts. Eight months earlier, in the fall of 1834, British abolitionist orator George Thompson made stops in Lowell while on a speaking tour of the U.S. that included lectures on “Slavery and the Bible” and “History and Results of West India Emancipation.”[28] The Boston antislavery newspaper The Liberator reported that Thompson’s audience at the Lowell Town Hall “was large and listened with delight until a late hour” on the first night of speaking, but on the second night, protestors tried to interrupt Thompson’s lecture with “stamping, vociferation, and hisses” and by throwing a brick that just missed Thompson’s head. The Liberator reporter, Lowell antislavery leader Asa Rand, distinguished between the “low company of fellows” who stamped and hissed, and the “gentlemen” who protested the formation of Lowell’s antislavery society but declined an invitation to Thompson’s lectures.[29]

Lowell’s gentlemen – mill agents and their associates – organized the 1835 anti-abolition meeting in Lowell. Manuscript notes on the meeting in the collection of Lowell History Center identify Kirk Boott, the powerful on-the-ground representative of the Lowell investors, as co-signer on a public call for the meeting, alongside other high-level employees of the corporations as the meeting’s organizers, including mill agents William Austin and John Aiken.[30] Cotton industry investors understood anti-abolition as essential work. Harrison Otis Gray, whose significant wealth was invested in Boston real estate and a Taunton, Massachusetts cotton mill, led a Boston anti-abolition meeting held a day before the meeting in Lowell.[31] Amos Lawrence, a Lowell investor whose family developed mills in Lawrence, Massachusetts on the Lowell model, traveled to cotton plantations in Georgia, Louisiana, and Alabama in 1836 and 1837 and assured planters of their shared interests.[32] In the same period, the Whig party dominated Massachusetts politics and counted among its ranks cotton industry investors Nathan Appleton, Amos Lawrence’s brother Abbott Lawrence, and Theodore Lyman II. Industry-friendly Whigs spread the anti-abolition message to town officers and business owners through personal relationships and party newspapers.[33]

In her study of Blackness and cotton, Black Bodies, White Gold, art historian Anna Arabindan-Kesson writes that “a speculative vision” – a constant looking forward to the next exchange – drove the U.S. cotton trade in the nineteenth century. Northern cotton industry investors and Southern cotton planters made decisions based on anticipation of the next harvest, the next sale, the next dividend.[34] Millions of pounds of cheap raw cotton enabled Lowell mills’ high dividends; the commodification of Black bodies enabled cheap cotton.[35] Plantation owners who supplied raw material to the Lowell mills purchased cloth produced in Lowell – “negro cloth” in mill records, “lowell cloth” in plantation records – to clothe enslaved Black laborers who harvested cotton.[36] Northern cotton industry investors imagined abolitionists’ disruption of future profits and committed themselves to eliminating the threat. Anti-abolition activism would secure the future of the trade.

The 1835 Lowell anti-abolition meeting took place on a Saturday evening in the Lowell Town Hall, removed from work sites and outside working hours. But talk of abolition and anti-abolition would have circulated through workplaces in Lowell. For some Lowell workers who created and controlled their workplaces, news-sharing and discussion was a seamless part their workday. John Levy, a Black barber who opened a shop in downtown Lowell in the 1830s, talked about antislavery politics with white clients while he shaved and trimmed.[37] “I began to discuss the question with my customers, in my shop at Lowell,” Levy recounted in his memoir. “By this conduct I rendered myself obnoxious to the people to whom the question was distasteful. I felt proud of being a volunteer in the cause of freedom, and I had always a copy of the ‘Liberator’ on my table.”[38] Asa Rand, a white minister and president of the Lowell Anti-Slavery Society in 1835, operated a bookstore on Merrimack Street from 1834 to 1836 where he may have discussed antislavery news with customers and friends.[39]

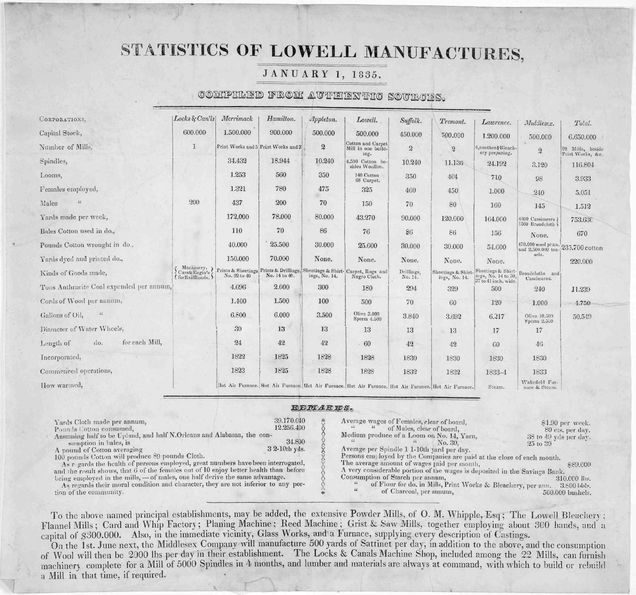

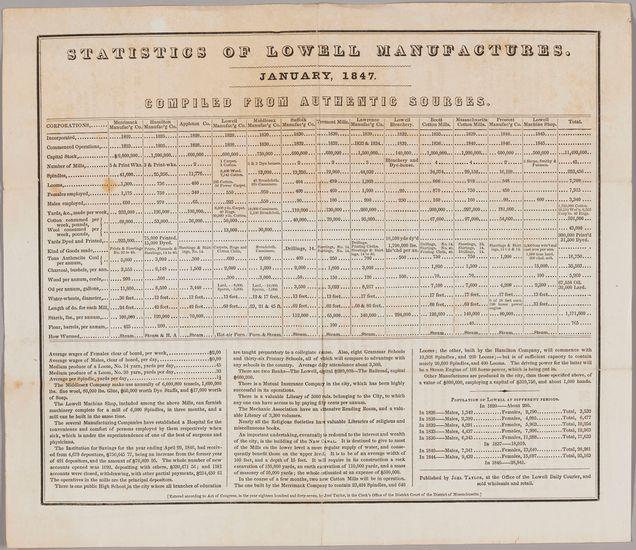

Just over five thousand white Yankee women worked in the Lowell mills in 1835, the majority under the age of thirty-five, and nearly all of them lived together in boardinghouses built and owned by mill investors.[40][41] Operatives worked for twelve to thirteen hours a day, six days a week, in noisy rooms. Talk about the noisy showdowns at George Thompson’s lectures or at Lowell’s anti-abolition meeting would have taken place during meal breaks, pauses at work, or after hours in boardinghouse rooms or in public spaces such as lecture halls and churches. Between 1832 and 1835 women in Lowell, including many mill operatives, organized a female antislavery society.[42] Together with women in other New England antislavery groups, they participated in a public practice of citizenship when they signed, and sought neighbors’ and co-workers’ signatures, on an antislavery petitions addressed to the federal government in 1836 and 1837.[43]

Lowell operatives who supported antislavery did so at the same time they expressed ambivalence about their conditions of work. Operatives who protested pay cuts in 1834 and 1836 by “turning out” – walking off the job – at once glimpsed and obscured their entanglement with slavery when they invoked liberty and bondage and warned that “the oppressing hand of avarice” would “enslave” them.”[44] Their language comparing factory work to slavery sounded a common theme in contemporary white labor reform that traded on racialized fear while dimly suggesting common cause with enslaved African Americans as fellow victims of coercive work culture.[45] Lowell’s antislavery societies were foundering by the early 1840s, due to “divisions in the ranks of its friends,” according to one observer, but re-formed and expanded during the 1840s and 1850s as abolitionism entered mainstream discourse as righteous cause alongside temperance and labor reform, and as Lowell became a fixture on abolitionist speaking tours and a safe haven for Black freedom seekers.[46]

Hissing, and appeals to stop hissing, would become standard fare at antislavery meetings in New England as abolitionism gained ground in the 1840s. In 1843, when a delegation of abolitionist lecturers visited Lowell on a packed New England tour, offended audience members issued a “volley of wrathful hisses from an hundred tongues,” while other audiences members offered “good-natured tokens of applause,” in response one speaker’s attack on the complacency of local clergymen. The same newspaper report described “considerable hissing” at a meeting in Lowell later in same day featuring speeches by abolitionists Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, William White, Parker Pillsbury, and John Collins, but noted that the audience stopped “when it was distinctly admitted that they had the right of hissing.”[47] Like the newspaper editors who either amplified or denied the story of noisy protest at the 1835 anti-abolition meeting, audiences who applauded or disrupted antislavery speech made claims about who and what deserved to be heard. In Lowell, where workaday lives were tied fast to the Southern slave economy, audience members’ claps and hisses expressed not only their moral and religious feelings, but also their investments in Lowell’s structures of work.

“reports of stone blasting”

In September 1846, Lowell mill operative Sarah Bagley published an attack on the Christian piety of cotton mill investors and their agents in the Lowell-based labor newspaper the Voice of Industry. Bagley was both an experienced weaver who had worked in the Lowell mills for ten years and a labor reform leader who co-founded the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association in 1844, spoke before the Massachusetts legislature in favor of the ten-hour work day in 1845, and served on the publishing committee of the Voice of Industry from 1845 to 1846. Bagley had publicly denounced the religious hypocrisy of mill owners before, in an 1845 pamphlet titled “Factory Life As It Is” published by the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association.[48] She addressed her 1846 critique to a Scottish newspaper correspondent who had published an admiring report on the famous American manufacturing city, citing Lowell’s “twenty-three churches” and the absence of “poverty,” “drunkenness,” and “rioting” as evidence of its high moral standard.[49]

Bagley challenged the Scottish correspondent’s sunny image of Lowell. Had they observed Lowell on a Sunday, Bagley asserted, they would have witnessed abundant evidence of desecration of the sabbath: “You might have seen workmen employed by the hundreds… you might have seen teams moving gravel … you might have seen a train of cars coming in from New Hampshire… loaded with workmen.” In addition to seeing work, they would have heard it:

You might have heard the reports of stone blasting, that would shake the foundation of the ‘twenty-three churches,’ and drown the voice of the man of God, who was dispensing the word of life to the agents under whose directions the work was performed.[50]

“This,” Bagley continued, “is the real, actual, practical religion of the corporations, a very different thing from profession.” Her styling of her target as “the corporations” reflected common usage among operatives in Lowell and points to Bagley’s and other workers’ recognition of the novel financial structures that made Lowell possible.[51] For Lowell’s labor reformers, “the corporations” were extensive, abstract, and powerful adversaries.

Bagley’s story about noisy sabbath labor reads as a parable of religious hypocrisy. Directing work on Sundays proved the corporations’ unholy zeal for profit, and their unconcern for drowning the voice of the minister, or shaking the church foundations, proved their faithlessness. Bagley invited her readers to picture mill agents in particular – local proxies for the Boston investors who controlled the mills’ daily operations – seated in their pews on Sunday before the muted minister, hearing not a sermon or Gospel reading but instead repeating explosions that signaled industrial expansion. Increasing their returns on investment, Bagley implied, was the corporations’ real “word of life.”

Bagley’s rhetoric was strategic, but the noise was real. Stone blasting was a job, performed by men hired as “outdoor hands” by the Proprietors of the Locks and Canals, the company that controlled waterpower privileges in Lowell.[52] The same year Bagley published her attack on the corporations’ religious hypocrisy, the Locks and Canals broke ground on an ambitious project to expand and retrofit their canal system in order to increase the number of lease-able mill seats. From the perspective of the mill owners, the Northern Canal was an investment on the same logic as the initial development of Lowell – a massive outlay of capital that promised high returns on investment – and a maintenance and upgrade project motivated by increasing market competition.[53] From the perspective of men seeking work, the Northern Canal represented opportunities for work after a slow hiring period at the mills. In his history of waterpower in Lowell, Patrick Malone found that between February and August 1846, the Locks and Canals increased their workforce from “17 mechanics and laborers” to over eight hundred.[54] The Locks and Canals classified them as “laborers” or “out-door hands.”[55]

The majority of the people who worked on the Northern Canal were Irish men.[56] They applied for work through the Locks and Canals’ superintendent of outdoor work, who had been on the job since the 1820s and may have known returning laborers by name.[57] Work on the Northern Canal included manual drilling, excavating hard rock with black powder explosives, moving gravel, earth, wood, and stones, and de-constructing and re-constructing wood and stone canal walls and other structures. A supervisor on the project described the scope of excavation work in his notebook, in terms that quantify and abstract the strenuous labor: “the daily work of a laboring man is raising 10 lb. to the height of 10 ft. in a second and continue this for 10 hours.”[58] Newspapers reported on the deaths of at least four workmen during the construction of the Northern Canal, including one, Michael Reefe, who was struck by falling rock.[59] In his history of Irish communities in Lowell, historian Brian C. Mitchell calculated that laborers working on the Northern Canal received on average $1 per day, slightly higher than the usual rate of 83¢, possibly because the work was dangerous and the timeline was short.[60]

Northern Canal construction was likely the noise in Sarah Bagley’s ear in 1846, but construction noise had been ongoing since the Lowell investors started buying land and water rights at Pawtucket Falls on the Merrimack River in 1821. The first Irish work crew arrived on the site in 1822, traveling by foot from Charlestown to apply to Kirk Boott for work as canal builders. Boott met the crew at a tavern and made arrangements with their foreman, and they started work the next day.[61] Later in the 1820s Irish men moved to Lowell with their families to take advantage of the seasonal construction jobs, including work on the canals as well as building streets, railways, mill buildings, and boarding houses; permanent jobs in the mills were reserved for Yankees.[62] Brian Mitchell tracks the slowly increasing numbers of Irish residents of Lowell throughout the 1820s and 1830s, and the rapidly increasing numbers after 1841, when new travel routes opened up from Ireland to Boston, and again after 1846, when effects of the Irish Famine were most devastating.[63] Contemporary newspaper reports and later histories of Lowell referred to the “huts,” “cabins,” “tents,” and “shanties” built by Irish families on land across the canal from the mill district that was known as the “paddy camp lands,” the “Irish camp,” “New Dublin,” and “the Acre” and “Half-Acre.”[64] The lively outdoor life and provisional appearance of the Irish neighborhood contrasted with the long, orderly rows brick boarding houses for Yankee women on the other side of the canal.

Bagley characterized the working men who carted gravel and blasted rocks on the sabbath as victims of corporate avarice who deserved the same protections as the Yankee operatives. For others in Lowell, the noise of blasting performed by Irish working men may have seemed of a piece with other experiences of Irish noise and disorder. A French-Canadian mechanic living in Lowell in 1840 was dismayed by the “great many Irish here” who “will get drunk and fight and then go to Church” and who “will at the death of a friend get drunk and howl over the body in a manner truly terrifying.”[65] Police reports in the Lowell Courier newspaper in the 1840s regularly named Irish men who disturbed the peace. A typical report from May 1841 teasingly described a “‘fight royal’ between the counties of Cork and Kerry” and listed Jerry Shea, James Moran, Morris Quinn, Tom Quinn and his five sons, Pat Horagan, and Kate and Nelly Fitzgerald as antagonists, victims, and witnesses. Morris Quinn “was held in $50 to keep quiet 3 months.”[66]

Kirk Boott responded to reports of Irish disorder by appealing to Irish Catholic leadership in Boston for help, and by donating corporation land for a Catholic church on the Acre. Irish men worked after hours to complete the construction of St. Patrick’s in 1831.[67] Although St. Patrick’s counted among the “twenty-three churches” cited by Bagley and the Scottish correspondent, it stood apart from Lowell’s Protestant church culture. For mill agents and for middle-class Irish people invested in respectability, St. Patrick’s functioned as a labor control mechanism, with only mixed success. Before construction was complete, a mob of Yankee nativists, allegedly angered by the church as a sign of Irish permanence in Lowell, attacked the church construction site and surrounding neighborhood but were held off by residents armed with stones, and eventually, by town officials.[68]

For textile mill operatives and other Lowell residents, the congregation of St. Patrick’s may have seemed more likely to disrupt than to suffer disruptions. Bagley’s description in the Voice of Industry of stone blasting disrupting the minister’s speech, and the mill agents’ inability to hear “the word of life,” would have brought to mind images of Protestant churches attended by mill agents and mill overseers such as St. Anne’s, the Episcopal church Kirk Boott established in 1825, or the John Street Congregational Church, established by mill agent John Aiken and others in 1839. Sound studies scholar Mark Smith has identified nineteenth-century “norms of genteel Protestant worship” in the U.S. including silence, solemnity, and discipline over emotions.[69] Many Lowell Yankees perceived Lowell’s Irish residents as embodying the opposite values: noisiness, passion, and disorder.

Bagley’s critique of sabbath labor in 1846 coincided with the end of the period when young Yankee women formed the majority of the work force in the Lowell mills. As Irish women seeking permanent employment began to fill positions in the spinning and weaving rooms, Yankee operatives remembered wistfully when their workplace was more social and day-to-day work discipline was less strict, even while agents and overseers took greater paternal interest in each worker. Some Yankee operatives jumped to make connections between the degradation of working conditions and the degraded nature of the incoming Irish workers. One Yankee operative writing in the Lowell Offering in 1849 warned that if operatives quit their positions in response to a wage reduction, “vacancies left by these substantial, well-educated, upright-minded girls will be filled by the Irish.” She elaborated on her objection to “the Irish” taking positions as operatives, explaining that “they are untidy, ignorant, passionate” and “the better class, even the middle class of our New England girls, will not be seen in the street with them, will not room with them, cannot find them in the least degree companionable.”[70] Bagley took a different position, arguing that the mill investors had failed all their workers, and labored to build a far-reaching coalition of working people that focused on the ten-hour work day but also supported abolition, land reform, temperance, and cooperative movements.

Critics likely viewed Bagley herself as a source of noisy interference, of both gender norms and workplace norms. A poem printed in the Voice of Industry in 1845 used a metaphor of noise to describe the work of labor reform: “Be the Voice of Industry / on every hill top heard.”[71] Bagley’s voice in particular stood out as loud, uncompromising, and female. Bagley left her position at the Voice of Industry in late 1846, explaining in a letter to a friend that the new Voice of Industry editor “found fault with my communications” and planned to eliminate the newspaper’s Female Department, which Bagley had introduced in early 1846 with assurances to readers that it would “not be neutral, because it is female.”[72] She lamented to her friend that the new editor believed “truth ought to be spoken in such honeyed words that if it hits any one, it shall not affect him unfavorably.”[73] Bagley’s metaphorical language offers a negative counterpart to noisy speech – smooth and palatable “honeyed words” – while suggesting that the effectiveness of the reformer’s voice lies in its capacity for physical impact.

“ringing in my ears”

In 1867, the labor reform newspaper the Boston Daily Evening Voice published a letter from “A Working Woman” in which she recollects her experience as a factory operative in the Lowell in the late 1830s. “A Working Woman” described both the appeal and the hardships of working in the Lowell mills and charted the development of her political consciousness. Witnessing firsthand the enviable condition of mill owners’ daughters, who were “tenderly cared for,” “had an abundance of leisure,” and could work or attend school “when they pleased,” she explained, moved her to reflect “on the injustice of society” and ultimately participate in the campaign for the ten-hour work day.[74] The working woman offered her story as part of an argument for shorter working hours, recalling how fatigue from overwork competed with her eagerness to educate herself by reading and attending evening lectures. “I am sure few possessed a more ardent desire for knowledge than I did,” she wrote, but “it was impossible to study History, Philosophy, or Science” after “ten to fourteen hours” of manual labor. At evening lectures it was too hard to hear, which she blamed in part on noisy interference in her ears:

I well remember the chagrin I often felt when attending lectures, to find myself unable to keep awake; or perhaps so far from the speaker on account of being late, that the ringing in my ears caused by the noise of the looms during the day, prevented my hearing scarcely a sentence he uttered.

In the working woman’s description, ringing in the ears, like stone blasting and hissing, rendered authoritative speech indecipherable. Unlike blasting and hissing, the ringing, “caused by the noise of the looms during the day,” was a sound that moved across time as well as space, following the working woman from the weaving room into leisure space of the lecture hall. Like the working woman’s other symptoms of poor health, the ringing in her ears was an example of employer-controlled work conditions taking hold of her body after work hours and outside the workplace.

The female operatives’ self-organized literary magazines, the Lowell Offering and its successor the New England Offering, include numerous references to noisy workplaces in fictional stories about mill work. Writers commented on the ways noise obstructed sociability or fostered introspection. In the fictional story “A Week in the Mill” published in 1845, the narrator recounts an operative’s limited opportunities for conversation with co-workers: “Now and then she mingles with a knot of busy talkers” or “holds converse with some intelligent and agreeable friend.” But since “the clattering and rumbling around her prevent any other noise from attracting her,” she is often “left to her own thoughts.”[75] In another story framed as a series of journal entries, a fictional operative describes her friendship with “a very pretty sociable girl in the mill, who comes and screams in my ear to tell my funny things, but I cannot understand her half the time.”[76] The noise of the machines did not prevent sociability in these stories, but it did determine its quality and extent.

In her 1889 memoir about working in the Lowell mills, Lucy Larcom described how her perception of mill noise changed during her time as operative in the late 1830s and 1840s. At first, “[t]he noise of the machinery was particularly distasteful to me,” she recalled, though she was determined that “its incessant discords” would not “drown the music of my thoughts.”[77] When Larcom returned to mill work after caring for family members for several months, her perspective on the noise of the machines changed. She found that she “enjoyed … the familiar, unremitting clatter of the mill, because it indicated that something was going on.” Larcom reflected that she particularly took pleasure in the company of her co-workers and the experience of collective work. “I liked to feel the people around me, even those whom I did not know, as a wave may like to feel the surrounding waves urging it forward…. I felt that I belonged to the world…”[78] The 1841 story “The Spirit of Discontent” published in The Lowell Offering also presented two distinct perspectives on mill noise. When the fictional operative Ellen Collins complains about “the clang of the bell” that calls her to work at an early hour, and confinement in “a close noisy room from morning til night,” her friend suggests that returning to her rural home may not resolve her frustrations. “What difference does it make, whether you shall be awakened by a bell, or the noisy bustle of a farm-house?” the friend asks, after inventorying the advantages of urban life in Lowell, including proximity to churches and access to books and evening lectures.[79]

Like the fictional operative, the anonymous working woman counted Lowell’s evening lecture programs as a positive part of her experience of mill work. Operatives’ enthusiasm for lectures reflected an interest in intellectual and moral improvement that pervaded nineteenth-century New England. Reading groups, circulating libraries, and lecture programs known as ‘lyceums’ appeared in seemingly every New England village and town in the 1830s.[80] Lowell operatives attended evening concerts, classes, improvement circles (where they prepared contributions to the operatives’ literary magazines), and lectures on science, religion, philosophy, and literature. The corporations sponsored many of these edifying offerings as part of their project to protect female operatives from corrupting influences, but the success of the lyceum lectures and improvement circles also related to operatives’ desire to prepare for something better than factory work.[81] Historians of the Lowell mills Caroline Ware, Hannah Josephson, and Thomas Dublin have demonstrated the high turnover of female operatives and the frequency with which they pursued cosmopolitan urban lives after a period of work in the mills.[82] The anonymous working woman noted that she entered mill work in order to “pay expenses at an Academy,” and that she worked in the mill for just three years.

The working woman’s letter shows a person engaged with the dynamics of work, power, and gender who sought to negotiate a measure of autonomy in her own work life. She linked her commitment to the campaign for the ten-hour work day to her desire to correct the injustice that allowed some people to “do as they pleased” while others experienced strict time discipline. At the end of her letter, she reflected on her preferred work arrangements:

And I will say in truth that if the hours of labor had been only eight instead of thirteen, I should prefer working in the mill to house work, enjoyed the society of the girls, and the noise of the machinery was not displeasing to me…

Like the fictional character who compared mill work to farm work, the working woman imagined a version of mill work that she would prefer to house work. The noise of the looms figured into her imagined version of mill work, but in these improved conditions “the noise of the machinery was not displeasing.” In the work life she would choose, with less time required on the job and more time to do what she pleased, the noise would become bearable or even enjoyable.

Conclusion

Stone blasting, hissing, and ringing in ears shut out the voices of the minister, the anti-abolition speaker, and the lyceum lecturer in Lowell in the first half of the nineteenth-century. Other voices, in turn, documented these noisy interferences, choosing words, forms of address, and mediums that served their own goals as witnesses, critics, resistors, or defenders of the status quo. Irish men noisily excavated rocky land, incidentally drowning out the Christian “word of life,” in order to materialize investment opportunities for distant owners. Sarah Bagley turned the church-disrupting noise into a damning parable that cast waged laborers as freedom-seekers and cotton industry investors as worshippers of dividends. Anti-abolitionists and abolitionists “hissed down” – condemned – each other’s speech in the Lowell Town Hall. Arguments for and against emancipation – gradual, immediate, and colonial – circulated through mill rooms, through Levy’s barbershop, and through newspapers that reached far beyond Lowell. The clatter, rattle, and hum of spinning frames and power looms dominated operatives’ experience of mill work and followed them off the job, but they were also familiar sounds that operatives associated with Yankee sisterhood and cosmopolitan urban life.

Stories about noise in Lowell in the first half of the nineteenth century show people reckoning with new work relations that seemed to be hardening into unchangeable facts of life. The anonymous working woman, looking back on her time as an operative in Lowell in the late 1830s, tentatively imagined the work life she would choose: social relationships with co-workers, factory work instead of housework, shorter hours with more time and energy for reading. In the “The Spirit of Discontent,” one fictional operative preferred the self-determined schedule of farm life; the other preferred the escape from household management she enjoyed as a Lowell operative.[83] Like the working woman and the fictional operatives choosing between farm and factory, many of the Lowell workers in this essay test their ability to control their work conditions. The noisy interferences I examine here each mark out moments of friction, when one bid for control interfered with another. Noticing these sticking points is a method for mapping New Englanders’ motivations and strategies in response to their first encounters with waged work.

[1] A small, well-connected group of Boston merchants plotted the creation of a model industrial city in New England soon after developing a lucrative modern cotton mill in Waltham, Massachusetts in the 1810s. The Waltham mill, masterminded by Boston merchant Francis Cabot Lowell, made profitable use of new power loom technology Lowell had observed in England, an advantageous mill site on the Charles River, and the cheap labor of young women from local farming families. Around 1815, Lowell and his associates determined to scale up their lucrative experiment on a larger site with access to more waterpower. They chose a site on the Merrimack River that would eventually become Lowell, Massachusetts. See Thomas Dublin, Women at Work: The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826-1860 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 17-22.

[2] “jar and whirl”: John Greenleaf Whittier, The Stranger in Lowell (Boston: Waite, Peirce, and Company, 1845), 22; “din and clatter”: “noise of hammers”: Michel Chevalier, Society, Manners and Politics in the United States, Being a Series of Letters on North America (Boston: Weeks, Jordan, and Company, 1839), 129; “thumpings”: “A Trip to Lowell, ” The People’s Journal, June 13, 1846, 328.

[3] “noisey factory”: Amy Galusha to Aaron Leland Galusha, 3 Apr. 1849, Letter 001, Galusha Family Collection, Lowell National Historical Park, Lowell, MA, https://libguides.uml.edu/c.php?g=542883&p=3724664; “din and clatter”: Marie Currier to Harriot Hanson Robinson, Oct. 12, 1845, in Allis Rosenberg Wolfe, “Letters of a Lowell Mill Girls and Friends and Friends, 1845-1846,” Labor History 17, no. 1 (1976): 98.

[4] “strange discord”: Harriet Farley, “Letters from Susan: Letter Second,” Lowell Offering, June 1844, 52; “click-clack”: Lucy Larcom, An Idyl of Work (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875), 80; “whizzing and spinning”: Josephine L. Baker, “A Second Peep at Factory Life,” Lowell Offering, May 1845, 98.

[5] Almira, “The Spirit of Discontent,” Lowell Offering, 1841, 113.

[6] “noisy tenement”: Ella, “Weaver’s Reverie,” Lowell Offering, 1841, 188; cannon fire: Elizabeth [pseudonym], “My First Independence Day in Lowell,” Lowell Offering, November 1845, 249; “disturb the peace”: see the “Police Court” section in the Lowell Courier between 1841 and 1842.

[7] The Iron Age, January 30, 1890, 171; “vacant soyle”: John Cotton, God’s Promise to His Plantations (London: Printed by William Jones for John Bellamy, 1634), 5; “barren wilderness”: William Hubbard, The Happiness of a People in the Wisdome of their Rulers Directing and In the Obedience of Their Brethren… (Boston: Printed by John Foster, 1676), 61. See William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1984), 54-81.

[8] J.H., “The Song of the Factory Hand,” Truth and Opinion, Supplement to Fiber and Fabric, October 17, 1896, 1.

[9] Mark M. Smith has studied the ways aurality and aural images are central to representations of industrialization in the U.S. The term “heard world” comes from Smith. Mark M. Smith, Listening to Nineteenth Century America (University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

[10] Smith, Listening to Nineteenth-Century America, 11.

[11] See Norman Ware’s description of this period as characterized by increasing demands on workers’ speed and attention. Norman Ware, The Industrial Worker, 1840-1860: The Reaction of American Industrial Society to the Advance of Industrial Revolution (Houghton Mifflin, 1924), xii-xiii and 106-124. Robert F. Dalzell charts the same phenomenon from the perspective of the owners of the Lowell mills. Dalzell also argues that the primary goal motivating the investors who developed Lowell was wealth preservation, rather than wealth production. Robert F. Dalzell, Enterprising Elite: The Boston Associates and the World They Made (Harvard University Press, 1987), 66-70.

[12] David A. Zonderman, Aspirations and Anxieties: New England Workers and the Mechanized Factory System (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 22-23.

[13] Mark M. Smith, “The Garden in the Machine: Listening to Early American Industrialization,” The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies, eds. Trevor Pinch and Karin Bjistervel (Oxford University Press, 2011), 39-57.

[14] Smith, Listening to Nineteenth-Century America.

[15] Kathi Weeks, The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries (Duke University Press, 2011), 5-8.

[16] Extra Globe (Washington, D.C.), October 2, 1835, 298.

[17] Niles’ Weekly Register, October 3, 1835, 74.

[18] Ibid.

[19] For evidence of speed-ups and other labor intensification practices: Caitlin Rosenthal, Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018), 85-120; Peter A. Coclanis, “How the Low Country Was Taken to Task: Slave-Labor Organization in Coastal South Carolina and Georgia,” in Slavery, Secession, and Southern History, eds. Robert Louis Paquette and Louis A. Ferleger (University Press of Virginia, 2000), 59-78; Philip D. Morgan, “Task and Gang Systems: The Organization of Labor on New World Plantations” in Work and Labor in Early America, ed. Stephen Innes (University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 189-200; Thomas Dublin, Women at Work, 109-113; and Zonderman, Aspirations and Anxieties, 33-35. Historians and scholars of the cotton trade have also noted the ways industrial machinery, such as the loom and the cotton gin, was subject to the logic of intensification.

[20] “Emancipationist,” “gradualist,” “immediatist,” “nonextensionist,” and “colonizationist” referred to distinct antislavery positions. “Amalgamationist” was a term used to incite fear by implying an equivalence between antislavery politics and support for “racial blending” at the level of the family.

[21] Lowell Journal and Mercury, September 4, 1835.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Niles’ Weekly Register, October 3, 1835, 74.

[24] “The Ethics of Amusement,” The Musical Record, April 1884, 10.

[25] “Hissing,” Littell’s Living Age, May 16, 1874, 444.

[26] “Hissing Actors,” The Week, November 30, 1872, 713.

[27] J. Walker, A Rhyming, Spelling, and Pronouncing Dictionary of the English Language (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1852), 311, 469.

[28] Z. E. Stone, “George Thompson, the English Philanthropist, in Lowell,” Contributions of the Old Residents’ Historical Association (Lowell, MA: Old Residents’ Historical Association and Morning Mail Print, 1883), 118-119, and Arthur L. Eno, “The Civil War: Patriotism vs. King Cotton,” Cotton was King: A History of Lowell, Massachusetts, ed. Arthur L. Eno (New Hampshire Publishing Company and the Lowell Historical Society, 1976), 128.

[29] A. Rand [Asa Rand], “Mr. Thompson at Lowell,” The Liberator, December 6, 1834, 194.

[30] Yukako Hisada, “George Thompson and Anti-Abolitionism in Lowell, Massachusetts,” Journal of the Faculty of Foreign Studies no. 46 (2014): 222-223.

[31] Thomas H. O’Connor, Lords of the Loom: The Cotton Whigs and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968), 52, and John Michael Cudd, The Chicopee Manufacturing Company: 1823-1915 (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1974), 15.

[32] Dalzell, Enterprising Elite, 180-181; O’Connor, Lords of the Loom, 48-49.

[33] Frederic Cople Jaher, The Urban Establishment: Upper Strata in Boston, New York, Charleston, Chicago, and Los Angeles (University of Illinois Press, 1982), 55.

[34] Anna Arabindan-Kesson, Black Bodies: White Gold: Art, Cotton, Commerce in the Atlantic World (Duke University Press, 2021).

[35] Ronald Bailey lists domestic cotton consumption in pounds per year for every tenth year between 1790 and 1860. Ronald Bailey, “The Other Side of Slavery: Black Labor, Cotton, and Textile Industrialization in Great Britain and the United States, Agricultural History 68, no. 2 (Spring 1994): 37. For nineteenth-century published sources for Lowell statistics, see for ex. an 1840 report on U.S. cotton manufacturing stating that Lowell mills consumed 18,059,600 pounds of cotton in 1839. James Montgomery, A Practical Detail of the Cotton Manufacture of the United States of America; and the State of the Cotton Manufacture of that Country Contrasted and Compared with that of Great Britain; with Comparative Estimates, (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1840), 172.

[36] Arabindan-Kesson uses “lowell cloth” or “negro cloth” as a touchpoint for reflection on the material, embodied experiences of the people who wore it. Arabindan-Kesson, Black Bodies, White Gold, 42-63. For historical sources that reference “lowell cloth” see: Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, [1936]. The UMass Lowell Library has collected all the narratives that reference “lowell cloth”: “Lowell Cloth,” UMass Lowell Library, Revised 19 Apr. 2021, libguides.uml.edu/c.php?g=546113. For examples of published sources that reference “negro cloth,” see: James Montgomery, A Practical Detail of the Cotton Manufacture of the United States of America; and the State of the Cotton Manufacture of that Country Contrasted and Compared with that of Great Britain; with Comparative Estimates (New York: Appleton & Co., 1840), 167; and John MacGregor, Commercial Statistics. A Digest of the Productive Resources, Commercial Legislation, Customs Tariffs, Navigation, Port, and Quarantine Laws, and Charges, Shipping, Imports and Exports, and the Monies, Weights, and Measures of All Nations vol. 3 (London: Whittaker and Co., 1847), 107, 108. South Carolina’s “Negro Act of 1740” states: “no owner … shall permit such Negro or other slave to have or wear any sort of apparel whatsoever, finer, other or greater value than Negro cloth.” In Lowell, each manufacturing company specialized in different textile products; the mill that produced “negro cloth” was the Lowell Manufacturing Company. The terms “negro cloth” and “lowell cloth” are also found in manuscript sources such as account books.

[37] Levy states that he was in business as a barber in Lowell around 1826 and again from 1833 and 1836. John Levy, The Life and Adventures of John Levy, edited by his Daughter Miss Rachel Frances Levy (Lawrence, MA: Robert Bowners, The Journal Office, 1871), 41, 47-52.

[38] Levy, The Life and Adventures of John Levy, 48. For a history of Black barbershops see: Quincy T. Mills, Cutting Across the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

[39] John Lytle Myers, The Agency System of the Anti-Slavery Movement, 1832-1837, and Its Antecedents in Other Benevolent and Reform Societies (PhD dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Abor, 1961), 205-206.

[40] “Statistics of Lowell Manufactures” [printed sheet], 1 Jan. 1835, Portfolio 56, Folder 10, Printed Ephemera Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., www.loc.gov/item/2021767203.

[41] Dublin, Women at Work, 75-76.

[42] Beth A. Salerno, Sister Societies: Women’s Antislavery Organizations in Antebellum America (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2005), 29; Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States vol. 1 (New York: International Publishers, 1962), 267. Foner dates the establishment of the Lowell Female Anti-Slavery Society to 1832; Salerno dates it to 1835, immediately following George Thompson’s lectures in Lowell.

[43] Edward Magdol, The Anti-Slavery Rank and File: A Social Profile of the Abolitionists’ Constituency (New York: Greenwood Press, 1986) and Susan Zaeske, Signatures of Citizenship: Petitioning, Antislavery, and Women’s Political Identity (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 78. Zaeske discusses Northern womens’ diverse understandings of petitioning as a public political practice, and the high stakes of women’s petitioning activity following the 1836 federal law prohibiting hearings on antislavery petitions.

[44] For histories of the turn-outs, see Dublin, Women at Work, 86-107 and Harriet Hanson Robinson, Loom and Spindle, or, Life Among the Early Mill Girls (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell and Company, 1898), 83-86; “oppressing hand”: Boston Evening Transcript 18 Feb. 1834.

[45] For discussions of operatives’ and other workers’ comparisons between factory work and slavery in labor reform rhetoric, see: David Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (New York: Verso, 1991); Julie Husband, “‘The White Slave of the North’: Lowell Mill Women and the Reproduction of ‘Free’ Labor,” Legacy 16, no. 1 (1999): 11-21; and Carla L. Peterson, “‘And We Claim Our Rights’: The Rights Rhetoric of Black and White Women Activists before the Civil War,” in Sister Circle: Black Women and Work, eds. Sharon Harley and the Black Women and Work Collective (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 140-143.

[46] Joseph Sturge, A Visit to the United States in 1841 (London: Hamilton, Adams, and Co., 1842), 143.

[47] N. P. R. [Nathaniel Peabody Rogers], “Letter to the Editor,” Herald of Freedom, March 1, 1844, 6-7.

[48] Sarah G. Bagley, “Factory Life As It Is. By An Operative,” Factory Tracts no. 1 (Lowell, MA: Lowell Female Reform Association, 1845).

[49] Sarah G. Bagley, The Voice of Industry, September 18, 1846, 2. Reports about Lowell that circulated abroad in the 1820s through 1840s often compared working conditions in Lowell to those of British manufacturing cities like Manchester. People in the U.S. and Great Britain perceived British manufacturing cities of places of suffering and moral degradation, and Lowell was considered an alternative model. Improving on the British manufacturing labor system was part of the designs of Francis Cabot Lowell and Nathan Appleton, the investors who masterminded the development of Lowell and its predecessor mill complex in Waltham.

[50] Ibid.

[51] For a detailed description of the financial structures underpinning the development of Lowell and the New England cotton industry, and contemporary responses to the corporation, see Philip Scranton, Proprietary Capitalism: The Textile Manufacture at Philadelphia, 1800-1885 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 13-16.

[52] In 1845, the owners of the mills who used the Lowell canal system became the sole owners of the Proprietors of the Locks and Canals and subsequently took up projects to maintain the canal infrastructure and increase waterpower. See Patrick M. Malone, “Surplus Water, Hybrid Power Systems, and Industrial Expansion in Lowell,” The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 31, no. 1 (2005): 21.

[53] Brian C. Mitchell, Paddy Camps: The Irish of Lowell, 1821-1861 (University of Illinois Press, 1988), 86.

[54] Malone, Waterpower in Lowell, 91.

[55] Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 31.

[56] Malone calculates that Irish men made up more than half of the Northern Canal workforce by 1848. Patrick M. Malone, Waterpower in Lowell: Waterpower and Industry in Nineteenth-Century America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 92.

[57] Malone, Waterpower in Lowell, 89; Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 27, 30.

[58] Samuel K. Hutchinson, “Northern Canal, 1846-1847,” Small Notebooks, Proprietors of the Locks and Canals Collection, Lowell National Historic Park, Lowell, MA. Quoted in: Malone, Waterpower, 91.

[59] Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 87.

[60] Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 88.

[61] Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 14-15. Mitchell notes that a small number of Irish families lived in the area near Pawtucket Falls before 1822, and Irish men worked as canal builders there in the 1790s, before the Boston investors who developed Lowell took an interest in the area.

[62] Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 87; Dublin, Women at Work, 146.

[63] Using a variety of statistical and literary sources, Mitchell estimates that Lowell’s Irish population was about 500, or 7% of Lowell’s total population, in 1830, and grew to between 1,500 and 1,800, or between 12% and 14% of Lowell’s total population, in 1837. Mitchell also references the 1855 U.S. Census, which lists 10,369 Irish residents of Lowell, or 27.6% of the total population, but this number excludes many American-born Irish-heritage residents. Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 34, 58, 83-85, 184.

[64] Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 7, 24.

[65] J. I. Little, “A Canadian in Lowell: Labour, Manhood and Independence in the Early Industrial Era, 1840-1849” Labour / Le Travail 48 (Fall 2001): 227.

[66] Lowell Courier, May 9, 1841. Mitchell and others discuss Irish residents’ strong identification with their ancestral counties, which shaped the organization of neighborhoods, work crews, and other aspects of social life.

[67] George Francis O’Dwyer, Irish Catholic Genesis of Lowell (Lowell, MA: Printed by Sullivan Brothers, 1920), 15; Peter F. Blewett, “The New People: An Introduction to the Ethnic History of Lowell,” in Cotton Was King: A History of Lowell, Massachusetts, ed. Arthur L. Eno, Jr. (Somersworth, N.H.: New Hampshire Publishing Company, 1976), 195.

[68] Mitchell, Paddy Camps, 32; O’Dwyer, Irish Catholic Genesis of Lowell, 15-17.

[69] Smith, Listening to Nineteenth-Century America, 103.

[70] “Rights and Duties of Mill Girls, Chapter X: Reduction of Wages for Factory Labor,” New England Offering, July 1849, 156.

[71] Voice of Industry, May 5, 1845.

[72] Sarah G. Bagley, “Introductory,” Voice of Industry, January 9, 1846, 2.

[73] Sarah George Bagley to Angelique Le Petit Martin, 13 Mar. 1847, Martin family correspondence, Box 1, Folder 7, Lilly Martin Spencer Collection, Ohio History Connection Repository, https://libguides.uml.edu/c.php?g=542883&p=3723895.

[74] Boston Daily Evening News, February 23, 1867.

[75] “A Week in the Mill,” Lowell Offering, October 1845, 218.

[76] “Extracts from a Journal,” New England Offering: A Magazine of Industry, November 1849, 265.

[77] Lucy Larcom, A New England Girl-hood, Outlined from Memory (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1889), 183.

[78] Ibid., 193.

[79] Almira [pseudonym], “Spirit of Discontent,” Lowell Offering, April 1841, 41-44.

[80] See Tom F. Wright, The Cosmopolitan Lyceum Lecture Culture and the Globe in Nineteenth-Century America (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013).

[81] Lucy Larcom wrote that the “Lyceum lectures” in Lowell were “more patronized by the mill-people than any mere entertainment.” Larcom, A New England Girl-hood, 252.

[82] Dublin, Women at Work, 31-32, 54-57, 70; Hannah Josephson, The Golden Threads: New England’s Mill Girls and Magnates (New York: Russell & Russell, 1967), 81-83 [first published in 1949]; Caroline F. Ware, The Early New England Cotton Manufacture: A Study in Industrial Beginnings (New York: Russell and Russell, 1966) [first published in 1931].

[83] Almira [pseudonym], “Spirit of Discontent,” 41-44.