Holly Wiegand

Holly Wiegand is a doctoral candidate in English at Boston University. Holly’s research and teaching chart interdisciplinary approaches to British and American literature and religion of the long nineteenth century. Her dissertation, “Bold Devotion: Female Religious Authority and Transatlantic 19th-Century Fiction,” tells a new story about how period women’s writing stages public female preachers and theologians within cultures that seek to silence them. Her graduate work has been supported by the BU Center of the Humanities. Portions of Holly’s research are also forthcoming in Legacy and the edited collection Victorians and Videogames with Routledge.

Dickinson on the Surface: Contemporary Children’s Editions of Dickinson and the Board-Book Canon

In 1891, two edited poems by American author Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) appeared in the popular children’s magazine St. Nicholas.[1] The famously reclusive Dickinson sent out only a handful of her almost 1800 poems to be published during her lifetime; the poems at hand, titled by the editors as “The Sleeping Flowers” and “Morning,” join reams of Dickinson poems that were modified by publishers, editors, and adapters during and after her life to fit a perceived poetic taste.[2] In contemporary literary studies, early edited Dickinson poems on the whole remain ephemera to be exhumed only as opportunities for comparison, favoring analysis of facsimile manuscripts or accepted scholarly editions. Yet as book historian Ingrid Satelmajer points out, the packaged St. Nicholas poems reveal how Dickinson’s editors and publishers sought to “introduce her into print culture,” pointing out that periodicals easily outsold books and stood as a bastion of nineteenth-century literary culture.[3] The St. Nicholas Dickinson poems point us to popular sentiments about Dickinson’s poetry and, moreover, how adults interpret children interpreting poetry. Even today, children’s book publishers re-package Dickinson and see her as children’s reading, evidenced in the slew of kid-oriented Dickinson collections ranging from young readers’ picture books to infants’ illustrated board books. Here, I examine five modern Dickinson collections for children as a growing archive of a kid-oriented canon: I’m Nobody! Who Are You?: Poems of Emily Dickinson for Children (1978), Poetry for Young People: Emily Dickinson (1994), Poetry for Kids: Emily Dickinson (2016), Little Poet Emily Dickinson: In Emily’s Garden (2019), and The Illustrated Emily Dickinson: 25 Essential Poems (2022).[4]

Taking up Dickinson children’s books as objects of analysis reveals a complex network of popular assumptions about poetry for kids. As picture books, these Dickinson editions specifically engage multivalent material and textual surfaces: the surface of the language, the surface of the page, and the surface of the book. I argue contemporary Dickinson children’s book editors arrange the surfaces of Dickinson’s poems to cultivate an accessible and consumable Dickinson poetry. These picture books craft this image of Dickinson by emphasizing her poems about nature, couching her poetry among playful illustrations of bugs, animals, and flowers to “make them irresistible, beguiling—and clearly understandable,” as the book jacket of I’m Nobody! declares.[5] Such editorial choices paint Dickinson’s poems as safe and simple, swerving away from Dickinson’s notorious complexity. I contend these children’s versions of Dickinson epitomize an accessible “surface reading” approach to literary interpretation: a posture of reading that foregrounds the “evident, perceptible, apprehensible” in interpretation, according to Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus.[6] The children’s picture books at hand are a collaborative multimodal effort among past and present authors, publishers, and illustrators. As such, Dickinson children’s books both represent and respond to surface reading approaches. In surface mode, Dickinson kids’ books epitomize the push for child-friendly versions of canonical literature in popular culture growing out of adult anxieties (and fantasies) about poetic literacy and cultural inheritance.

Dickinson picture books offer an evocative case study for approaching the “board-book canon,” as I call it, by identifying the surfaces, audiences, and philosophies of reading within the children’s literature genre: the publisher/curator, the editor, the illustrator, and the adult purchaser. The Dickinson “board books” at hand (books constructed from durable paperboard for children), these Dickinson editions are calculated to spark a child’s interest in and understanding of poetry through its many surfaces. In brief, “surface reading” as an exterior interpretive posture arises in reaction to an inward excavatory approach of “symptomatic reading” made popular by Frederic Jameson.[7] Symptomatic reading seeks to diagnose hidden or unsayable codes and meanings “represse[d]” beneath “the surface of the text,” in Jameson’s words.[8] As Best and Marcus point out, this interpretive posture might be traced to Freud’s understanding of the unconscious and takes many forms.[9] Symptomatic reading is akin to “suspicious reading” and “reading against the grain” of a text in order to attend to its silences and how those silences often have real socio-political stakes, particularly for figures and ideologies often relegated to covert spaces and signs.[10] In contrast, Best and Marcus encourage us not to forsake the obvious for the obscure. Pushing back on suspicious reading, they summarize, “A surface is what insists on being looked at rather than what we must train ourselves to see through.”[11] Marcus’s investigation of female friendship in Victorian novels exemplifies this approach, arguing for “just reading,” seeing the surface text as “ample” for analysis.[12] Surface reading, then, holds kinship with “reading with the grain” and Eve Sedgwick’s “reparative reading” among other coinages.[13]

In scholarly conversation, Dickinson remains a prime candidate for both symptomatic and surface reading approaches for a host of compelling reasons ranging from biography (her reclusive spinsterhood and complicated sexuality) to publication history (her complicated legacy of editorial targeting) to language and genre (her complicated poetry).[14] Dickinson stands as the dominant female poet of the nineteenth century in part because of the never-ending complexity of her life and work. Surface readings of Dickinson largely attend to her manuscript facsimiles, as exemplified first by Ralph W. Franklin’s 1981 two-volume publication of Dickinson facsimiles in The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson and Marta L. Werner’s 1995 Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios, the latter of which lovingly reproduces photos of manuscripts side-by-side with transcriptions and analysis; the scholarly text itself forces us to attend to Dickinson’s surfaces in its scrapbook-like format.[15] Yet as Domhnall Mitchell summarizes, manuscript surface supremacy in Dickinson scholarship can tend toward a limiting (and limited) interpretive road. Mitchell suggests that emphasizing the manuscript implies “not only that there must be right and wrong textual approaches, but also that there are right and wrong texts—original and corrupt versions.”[16] Mitchell rightly points out that elevating Dickinson’s archives brings about problems of access equity and exclusionist critical approaches when, as Satelmajer represents, there is much to gain from analyzing Dickinson’s edited works and children’s editions.[17] Dickinson materiality scholars emphasize an ethos of fidelity, immediacy, and intimacy that privileges the authorial manuscript surface; Dickinson children’s book producers emphasize a different kind of fidelity, immediacy, and intimacy that privileges engagement with multimodal surfaces—and the consumer.

Reading surface does not mean forsaking depth but being alert to the exterior and the literal, therefore offering a useful methodology in children’s literature analysis and studies of adaptation. Surface study, Best and Marcus indicate, might attend to the physical materiality of the text, invest in formalist concerns of structure and design, attend to digital humanities analysis and cross-text comparisons, or simply contend for a literal interpretation of the words on the page. I wield and explore each of these various surface reading approaches to help sort out the networks of interpretation and intention of Dickinson’s works. I perceive these Dickinson children’s editions as doing surface reading as well as the books facilitating it. Material surfaces in children’s books are destined for years of wear and tear, to be cast aside, re-gifted, or stored away. And, particularly in adaptations, abridgments, and collections of established literary works for kids, textual and visual surface reigns supreme. Children’s literature scholar Peter Hunt suggests “the study of children’s literature brings us back to some very fundamental concerns: why are we reading? what are books for?”[18] I follow Hunt in arguing that children’s literature similarly returns to questions of how we read and what surfaces we value—consciously or unconsciously—in that reading. Kids’ books clue us into how adults interpret Dickinson as a cultural figure.

Illustrated children’s books geared toward aesthetic and ideological formation in U.S. culture like the Dickinson books at hand have a long history traceable to Benjamin Harris’s 1690 New England Primer, an alphabet book of couplets and correlated illustrations drawn from the Bible.[19] In the nineteenth century, as modern views of the home, the family, and the individual began to emphasize childhood as distinct from adulthood, children’s literature exploded.[20] Children’s picture books and primers of the past and present seek to prime children for adult reading and, moreover, for reading and being in adult society and culture.[21] Following children’s pedagogy scholar Hong-Nguyen (Gwen) Nguyen, I emphasize poetry reading as a social act emerging from, engaging, and creating literary culture.[22] Nguyen builds on sociocultural theories of child literacy and psychology, which emphasize students’ prior knowledge, cultural backgrounds, and social contexts to scaffold future work, “building on what children bring,” to quote Catherine Compton-Lilly.[23] Nguyen’s research on children learning to read haiku suggests that children reading poetry with an adult is not only an inherently social activity by relating to others through individual reading but also “a visible and irreducible joint production” among the poem, the adult reader, and the child learner.[24] Sociocultural literacy theory offers useful foundations for analyzing children’s poetry and the children’s poetry publishing industry in tandem with surface reading because of its attention to interacting interpretive tools and forces within texts and within the reading moment. Surface reading shows us that contemporary Dickinson editions emerge from and seek to build on “what children bring” culturally—a culture in which Dickinson is a popular figure in the Western canon. Close reading the surfaces of Dickinson children’s books points us to the utility of a sociocultural surface reading as a theory and method for approaching the board-book canon broadly.

Dickinson children’s editions uniquely manifest the tensions between simplicity and complexity, image and language in Dickinson’s poetry as well as the tensions between adult consumer nostalgia and creative adaptation in pop-culture Dickinson editions. The board-book canon grants us important insight into how contemporary culture considers literary legacy. And despite being transparently objects of cultural capital, these texts help emphasize the playfulness and vibrancy of Dickinson’s poems. They belong in conversations about Dickinson’s poetics because they urge us to consider afresh how we read Dickinson (in culture and in scholarship) and what surfaces we value in that reading.

Poetic Imagery, Illustration and Interpretation for Kids

Surface is supreme in contemporary Dickinson children’s literature: pages are made to be touched and turned, images and language flow in and out. These editors, illustrators, and publishers make strategic decisions based on their view of Dickinson, their view of how to read her poetry, and their view of how children will read her poetry. Comparing each of the five selected Dickinson kids’ picture book collections as both exemplifying and responding to surface reading modes, I will show, reveals little about how children actually engage with Dickinson’s poems and more about the editors’ assumptions about children’s intellectual habits and what makes a poem “for kids” and not for the adult reader. Scholar of children’s literature David Rudd identifies “three elements” at play in kids’ books: “the texts, the children, and the adult critics.”[25] I suggest, however, the Dickinson board-book canon trend only privileges the canon and the adult—the literary-minded consumer.

Even in a scholarly collection of children’s poems like the Oxford Book of Children’s Verse in America (1985), editor Donald Hall selects eight Dickinson poems as “for kids,” though suggesting these poems are “suited to children” and Dickinson “not at her best.”[26] Each of Hall’s eight poems appears in at least one of the illustrated children’s collections I examine. Hall seeks to historicize—and, implicitly, excuse—Dickinson as a children’s author in nineteenth-century poetic culture. He notes that “children’s magazines made much of Emily Dickinson” and claims that Dickinson joins a larger “current of childishness” in the poetic culture of the period, contending in sweeping historical judgment that in the nineteenth-century popular view “to be a poet was to be childlike.”[27] Hall sees Dickinson emerging from and contributing to a poetic culture for kids in broad, undefined terms. To sidestep his far-reaching (and here, uncorroborated) claim about nineteenth-century poetics, Hall’s comments illustrate the slipperiness and arbitrariness of identifying what poetry for children means, fluctuating between authorial intention, reception, tradition, and what he calls “structural intention.”[28] Even if the other editors concur with his poetry selections, Hall’s derogatory comment about what Dickinson poems are for children—Dickinson “not at her best”—suggests Hall sees surface simplicity as a lack of skill.

The host of illustrated children’s editions of Dickinson represents a strong stance about the importance of images in interpreting Dickinson and maintains that Dickinson is an author for children’s poetic consumption and appreciation. Published almost a decade before Hall’s Oxford Book of Children’s Verse, Stemmer House Publisher’s I’m Nobody! Who Are You? is the first modern illustrated Dickinson kids’ book. Stemmer House forwards a strong surface-oriented entry into Dickinson children’s books. I’m Nobody! is directed toward English readers ages 9 to 10 and includes a kid-friendly biographical introduction by Yale English professor Richard B. Sewall. However, the language and tone of the book’s jacket are clearly geared toward adult purchasers and suggest a non-academic author in its stress on simplicity and surface:

So many of the poems of Emily Dickinson seem made to delight children that we have asked a gifted artist, Rex Schneider, to interpret all those in this book with full-color illustrations. Thus, for the first time, the whimsical and thought-provoking images created by this great American poet are surrounded by marvelous pictures that make them irresistible, beguiling—and clearly understandable.[29]

Clunky grammar aside, the publishers of I’m Nobody! announce Dickinson as simultaneously a children’s poet and yet also as a poet needing illustration for reader comprehension. Added visual surface helps explicate the linguistic surface.

As scholar Perry Nodelman explains in his theoretical consideration of children’s book illustrations, the purpose of illustrations is to “assist in the telling of stories” and “bear the burden of conveying most of the information” because they take up the most space.[30] Illustrations are interconnected with text on the page surface and cannot but affect meaning-making; reading involves images as well as words. Poetry for Young People similarly declares that illustrations shape, simplify, and codify multiple poetic interpretations and “meanings” into a singular meaning; “An ideal way to introduce young readers to the marvels of poetry, the Poetry for Young People series opens up the world of wonderful word images by pairing classic poems with beautiful, related illustrations and providing helpful definitions and commentary,” the jacket explains.[31] Certainly, young readers benefit from kid-oriented scaffolding to sort out Dickinson’s “word images.” In blending metaphors of writing as painting, these pieces of surface scaffolding are loaded theories of poetry and poetic interpretation. Stemmer House’s description illustrates the affinity between Dickinson’s poetic “images” and Schneider’s “pictures,” and Poetry for Young People similarly praises Dickinson for “[u]sing words as her brush, she paints vivid pictures of the world around her.”[32]

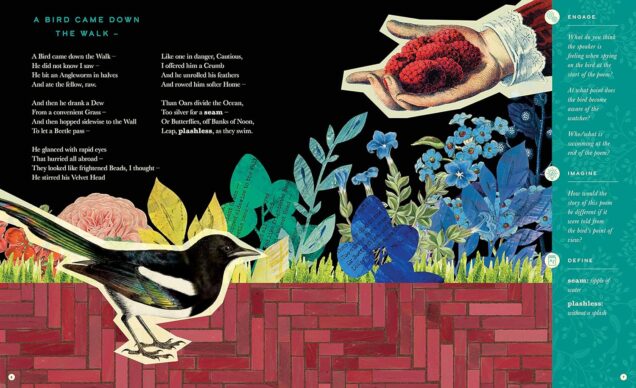

Both I’m Nobody and Poetry for Young People rely on surface reading postures to familiarize Dickinson’s complexity, particularly in their discussion of her “riddle poems”—poems that describe a subject or idea but do not name it, leaving the reader to deduce that subject or idea. In Bolin’s Poetry for Young People, an introduction aimed at young children summarizes Dickinson’s biography, and the jacket author swings between Dickinson as simple and surprising: “See the beauty and magic of the everyday world through the eyes of Emily Dickinson, one of America’s best-loved and most renowned poets. Flowers, birds, sunrises, sunsets, the moon, and even her own existence take on surprising meanings.”[33] The natural world becomes both legible and illegible in the author’s insistence on familiarity and surprise, foreshadowing the book’s interpretation of several Dickinson poems as “riddles.” Bolin’s edition explicitly speaks of seven of its Dickinson poems as “riddles” with the “answers” printed upside down in small font at the bottom of the page, urging readers to “cover the pictures” to not spoil the answer. I’m Nobody! offers a similar strategy for Dickinson’s riddle poems: “Some of the most delightful poems hide their meanings like little puzzles, until their last stanzas; and these we have arranged in such a way that the surprises are kept to the very end.”[34] Yet ultimately these picture books emphasize surface because of their emphasis on illustration as interpretation. As I’m Nobody! contends, “Sometimes [the poems] speak most directly. Sometimes they yield their meanings the way roses open, one petal at a time. […] Other poems happily allow the reader to find out not only their meanings but their subjects […] To these Rex Schneider brings vivid pictorial imagery which provides the key to understanding.”[35] Stemmer House’s philosophy exemplifies Nodelman’s analysis of the power of pictures. Yet because illustrations hold the most emphasis, the power and play within Dickinson’s riddles are undercut immediately: illustrations give away the “key” as surface image supersedes surface text. Poetry for Kids’ short poetic summaries of “What Emily Was Thinking” in the back of the book cannot compete with illustration. The Illustrated Emily Dickinson’s “Engage” and “Imagine” question prompts on the side of each page make a better attempt to engage the reader in poetic interpretation and critical thinking, adding a linguistic surface that addresses the reader directly. Nevertheless, illustration, even the most abstract, dominates.

Dickinson’s Birds, Bees, and Bugs

According to their dust jackets, contemporary Dickinson picture books seek to offer their young readers both surprise and sophistication alongside simplicity and surface. These books are awash with colors, shapes, and, most of all, critters. The five Dickinson kids’ books consistently select and emphasize Dickinson’s poems about the natural world. Natural subjects are easily representable in illustration and (likely) already identifiable by children. Illustrations of Dickinson’s birds, bees, and bugs are a clear example of publishers and editors “building on what children bring,” to remind us of Compton-Lilly’s philosophy of child literacy. The Oxford Book of Children’s Verse selects 8 Dickinson poems, I’m Nobody! selects 45, Poetry for Kids selects 35, Poetry for Young People selects 36, Illustrated Emily Dickinson selects 25, and In Emily’s Garden selects 8; together these children’s books mark 89 of Dickinson’s 1800 poems as children’s poetry. Five of the six Dickinson books include “A narrow fellow in the grass” (which addresses a snake) and “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” (which addresses a frog). Children’s book editorial selections mirror Dickinson’s oeuvre: Stanley Plumly notes that birds appear in 220 of Dickinson’s poems—the dominant creaturely image before bees and then butterflies.[36] All six of the children’s books at hand include the twenty-line “A Bird came down the Walk,” an 1862 poem in which a speaker observes a bird eat an “angleworm” and engage in other bird behavior before soaring away after the speaker offers “him” crumbs.[37]

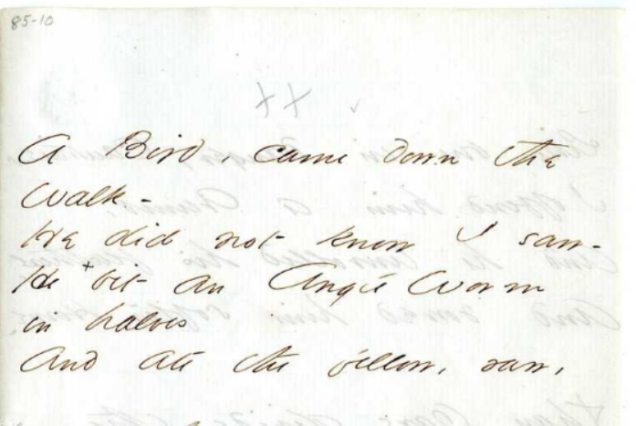

Here, I compare the children’s editions of “A Bird came down the Walk” and their accompanying surfaces and illustrations, beginning with Dickinson’s manuscript, to investigate how these surfaces cling to a simple and kid-friendly Dickinson despite the linguistic complexity in the poem’s final lines. Contemporary children’s picture book treatments of “A Bird came down the Walk” uniquely draw out the tensions between metaphor and image. In clinging to surface, they ironically reveal Dickinson’s complexity by way of contrast. Dickinson’s “A Bird came down the Walk” can be read as a kids’ poem because it stages a humble and realistic encounter between the speaker and the bird—“I offered him a Crumb.”[38] As John Felstiner points out in his reading of the poem, this bird is anthropomorphized in “com[ing] down the walk,” and familiar even in its Darwinian deed of eating the worm.[39] Richard E. Brantley posits that Dickinson’s “tone celebrates the scientific sense in which both she and the bird share common ground” amid the cruelty and beauty of the natural world.[40] The first stanzas of the poem paint a clear image (see fig. 1).

Franklin transcribes the first stanza of the poem thusly, maintaining Dickinson’s signature capitalization and dashes:

A Bird, came down the Walk –

He did not know I saw –

He bit an Angle Worm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw,[41]

Each of Dickinson’s contemporary children’s publishers and editors, save for In Emily’s Garden, regularizes the capitalization and punctuation throughout the poem. Poetry for Kids, for example, eliminates the dashes altogether and adds punctuations to the end of clauses:

A bird came down the walk

He did not know I saw;

He bit an angleworm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw.[42]

This regularization mirrors the methods of St. Nicholas editors Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd in prepping Dickinson for children’s reading.[43] The regularized addition of end marks at once both smooths and sections the poem into digestible ideas, removing the ambiguity of the dashes and the dynamism of the hanging comma. Nancy Walker points out that the specifically “raw” worm here emphasizes a human perspective in a “whimsical personification.”[44] The period here underscores this whimsy as a place where the adult reader might pause to laugh at the bird, seeing this act as ridiculous.

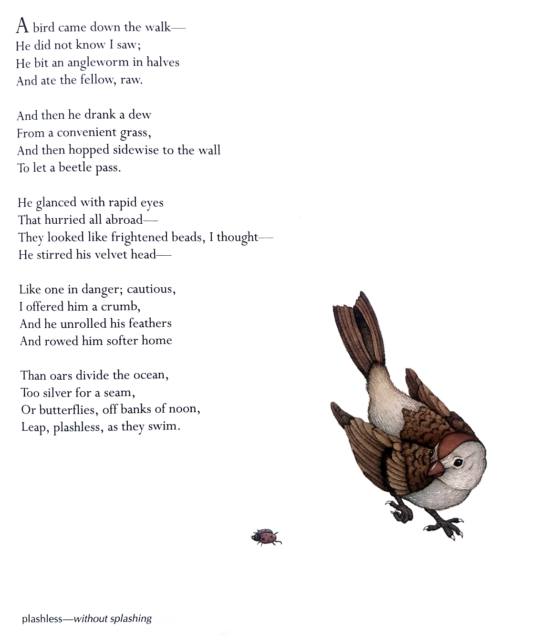

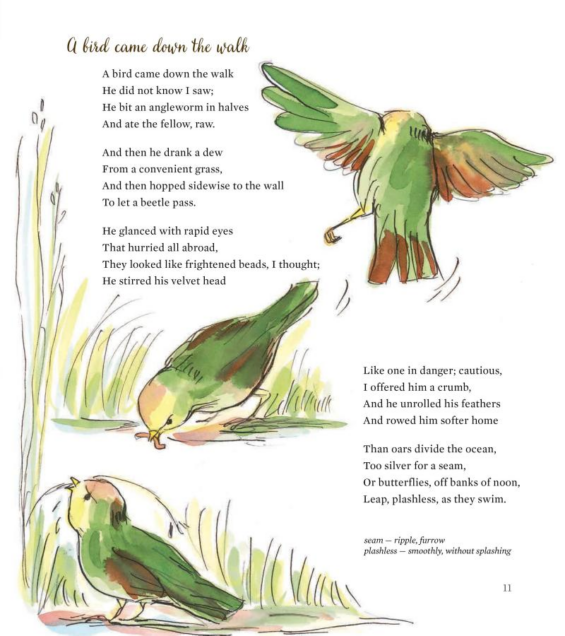

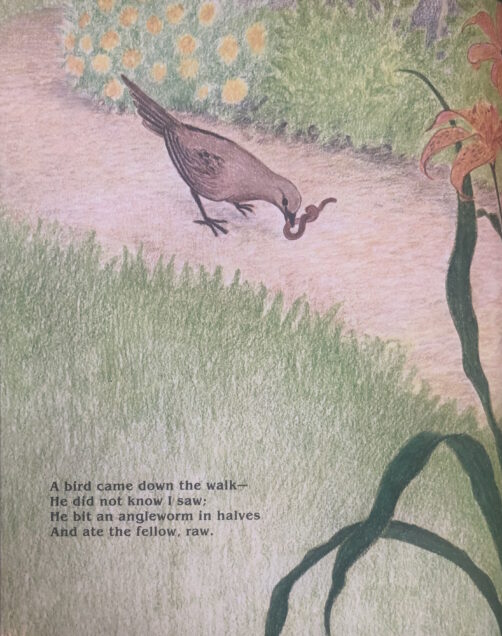

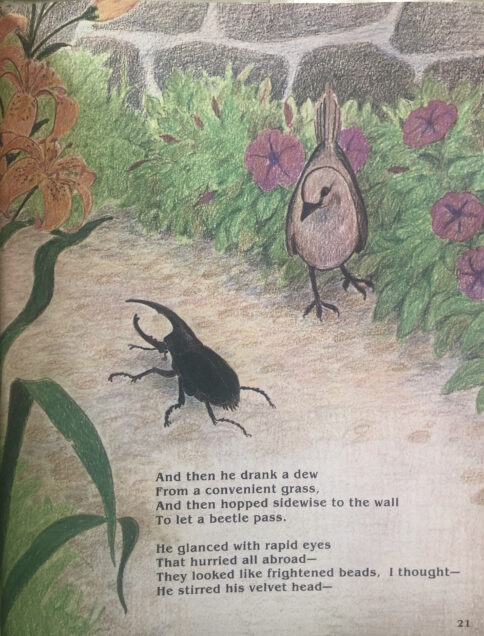

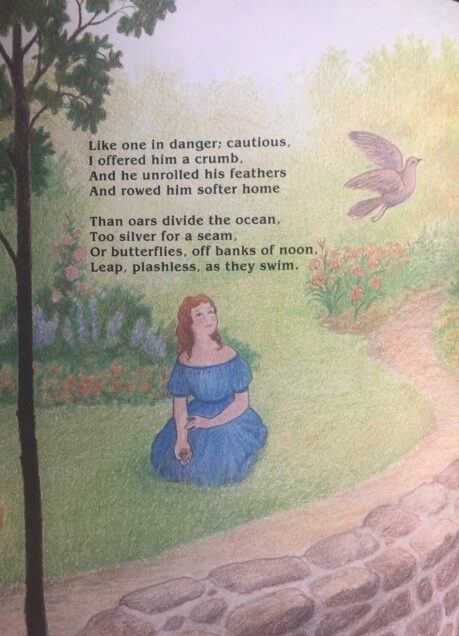

Illustrations of “A Bird came down the Walk” emphasize the bird, of course, because a bird is a familiar, identifiable subject in a kids’ book. Poetry for Young People’s illustrator, Chi Chung, frames this poem with a small illustration of a brown bird, perhaps a sparrow, walking across the page’s capacious white background, peering at a small ladybug to its left (see fig. 2).[45] Poetry for Kids’s illustrator Christine Davenier emphasizes this first stanza in a triptych-like watercolor series of the bird eating the worm, turning to the invisible speaker, and taking flight (see fig. 3). I’m Nobody!’s Rex Schneider allots the poem three full pages of warm colored pencil illustration, tracking the bird in three actions: eating the worm, letting “a Beetle pass,” and finally taking flight above a young Dickinson stand-in (see fig. 4-6).[46] Carme Lemniscates in In Emily’s Garden shows us a bright blue jay on an abstracted red background, strutting proudly down the sidewalk (see fig. 7-8). The Illustrated Emily Dickinson’s collage pages feature a large magpie outlined against a black background below a raspberry-filled girl’s hand (see fig. 9).

The illustrations above are safe, approachable, engaging. Each of these illustrations emphasizes the bird as the central poetic subject; we see different birds and bugs but little to no full human presence save in I’m Nobody! Human absence, counterintuitively, makes the poem more relatable and immersive. Without an illustrated human proxy, the child more easily immerses themselves in the world of the poem to identify with the poetic speaker finding meaning in the bird’s movements through this human-animal encounter. Dickinson’s “A Bird came down the Walk” feels kid-friendly as well because of its seemingly simple storytelling and its rhyming iambs; the poem is easy to read aloud and easy to memorize. Yet this surface safety and familiarity explodes in the final lines as the bird takes flight, becoming distant and strange.

Dickinson complicates the language surface with a network of metaphors about that flight—a complication that is impossible to represent in simple children’s illustrations: “he unrolled his feathers, / And rowed him softer Home / Than Oars divide the Ocean, / Too silver for a seam / Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon, / Leap, plashless as they swim.”[47] The bird unrolls like a carpet or a scroll and deftly cuts the horizon like a rowboat in its flight to finally become like a butterfly. Dickinson layers natural imagery, blending sky and sea and bird and butterfly in a confusion of surfaces and signs. In Felstiner’s words, “Dickinson wades into the ocean toward creatures somewhere sometime out of mind. […] ‘Banks of Noon’ snaps our synapses, leaves us blinking into midday sun.”[48] The bird transcends its natural state to become a dynamic spectacle of language soaring away from view. Dickinson plays with surface meaning and complexity as the bird escapes language and image. Indeed, there is a “surprise” and “riddle” to this poem, but not in the senses the publishers described above wherein the reader discovers the satisfaction of closure. Instead, the poem struggles against its surrounding surfaces and itself flies away. These children’s editions distinctively (and on the editor’s part, inadvertently) reveal the pulls between metaphorical and concrete image, surface and suspicion in Dickinson by making that tension visible on the page: Dickinson’s description of flight transcends the in-flight illustrations, too. The poem liberates itself from the illustrations around it.

Building the Board-Book Canon

“A Bird came down the Walk” illustrates the superficiality of contemporary children’s book editors and publishers’ characterization of Dickinson’s “kid poems” and what approaching them looks like. If “Banks of Noon” baffles the adult critic, how can children understand it? These are the “whimsical and thought-provoking images” Dickinson is known for indeed. The primary aim of these books, though, is to incite a lifelong interest in poetry—not to ensure full reading comprehension. Poetry for Young People asserts its collection is “[a]n ideal way to introduce young readers to the marvels of poetry.” Turning finally to a close examination of In Emily’s Garden and the BabyLit children’s series underscores what the other Dickinson children’s books imply: these texts are produced to instill poetic literacy and also canon surface literacy—the ability of children to learn canonical texts, characters, images, and ideas early in order to pursue them more fully as their reading levels develop. In other words, the commercialization of Dickinson relies on surface reading.

BabyLit was created by Suzanne Gibbs Taylor, the Publisher and Chief Creative Officer at Gibbs Smith Publisher, as “a fashionable way to introduce your child to the world of classic literature, while learning numbers, sounds, animals, colors, and more!” according to the back of the Classic Collection boxed set.[49] BabyLit advertises that their board book market is 0-3-year-olds, and, at the time of writing, their “classic” board book literature series includes twenty-two titles ranging from Anna Karenina as a “fashion primer” to Moby-Dick as an “ocean primer” to Romeo & Juliet as a “counting primer.”[50] In Emily’s Garden is the contemporary children’s edition of Dickinson with the youngest target reading level: each page spread includes just one line from a Dickinson poem, each of which refers to a bug, flower, or bee. In Emily’s Garden is part of the “Little Poet” series, joined by Robert Frost, and functions as a primer for garden creatures and Dickinson’s diction: the book teaches both what a hummingbird is and what a “sepal” is (the green outer portions of a developing flower bud).[51] Even in BabyLit’s selection of Dickinson’s lines, Dickinson’s complicated language and range of surfaces seem unavoidable. As Beverly Lyon Clark emphasizes in her analysis of BabyLit’s Little Women, BabyLit books “erode the segregation of adult and baby audiences,” and the market for these children’s editions is the adult reader and “adult purchaser.”[52]

I am (and have been, I freely admit) the ideal BabyLit target: the type who thinks about literature, literacy, and “classic” literary texts.[53] I’ve gifted several of my expecting friends the Classic Lit A to Z: A Babylit Alphabet Primer—with its delightfully absurd specificity of “Q” for Don Quixote—to both amuse my friends and, with any luck, ignite their kid’s curiosity about characters and stories I love. These books are charming and cute. Taylor explains that this impulse is BabyLit’s exact motivation: “it’s never too young to start putting things in front of them that are a little more meaningful, that have more levels […] It’s not so simple as, ‘Here’s a dog, here’s the number 2.’”[54] By 2013, the BabyLit series had already sold around 300,000 books and gained even greater attention through Julie Bosman’s The New York Times article that year.[55] Yet, in her essay for Inside Higher Ed, Carolyn Foster Segal questions BabyLit’s material and aims: “I’m not quite convinced of the value of introducing a 6-month-old to Moby-Dick or Les Miserables” because “[s]uch an endeavor must clearly involve a great deal of judicious revision. Does Ahab’s line ‘We become the thing we hate’ now read ‘We become the thing we teethe on’?”[56] Segal probes BabyLit’s adaptation of adult-oriented novels and sees the broader project as “absurd”—the board book is not nearly capacious enough for deep content and themes.[57] Segal concludes her essay by sardonically pitching new additions to the series like “Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury: A Boxed Set of 2 Classic Crying Primers.”[58] Segal’s tone throughout is skeptical, asking: Can we really adapt complex literature (like Melville, like Tolstoy, like Dickinson) into children’s books? Ought we? What are we actually accomplishing?

Looking outward towards the broader board-book canon, we find that children’s editions of literature and poetry are nothing new, and continuing to attend to our expectations about what and how a child reads is crucial to the broader project of expanding the canon and challenging notions of canonicity itself. Attending to the interdependent, contradictory surfaces of a “classic” for kids tells us more about our idealism, nostalgia, and anxiety than the intellectual and emotional processes of children reading. To extend Segal’s suspicious reading of BabyLit, it is crucial to also interrogate which “classic” books are and are not included in series like BabyLit or its counterparts, Chronicle Books’ “Cozy Classics” or Union Square Kids’ “Classic Starts,” each of which principally feature white English-speaking authors and narratives.[59] These texts signal Western cultural capital.

Nevertheless, Dickinson books for kids give us insight into Dickinson’s work by reflecting the values of surface reading: new surfaces and contexts lead to new insights about Dickinson’s poetics and how we interpret her poetry and legacy. I will likely pass on this collection of Dickinson books out of my own hope to plant seeds of interest in Dickinson. Dickinson’s deceptively simple “childlike” birds, bees, and bugs work better than adaptations of fiction because the poems’ surfaces respond to growing readers as they begin to read more suspiciously and imagine what it means for a bird to “unroll[] his feathers / […] Too silver for a seam”—an image that moves in, around, and beyond surface.

[1] I wish to thank Nick Bloechl, Noa Saunders, and Meghan Townes for their time and generous and incisive feedback in the writing of this essay. “The Products of my Farm are these / Sufficient for my Own / And here and there a Benefit / Unto a Neighbor’s Bin,” Emily Dickinson, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition, ed. R. W. Franklin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999), 425.

[2] After the bulk of Dickinson’s nearly 1800 poems were uncovered by her family after her death in 1886, Dickinson’s sister Lavinia pursued publishing, enlisting Mabel Loomis Todd (1856-1932) and Emily’s longtime correspondent Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1823-1911). Todd and Higginson published Poems of Emily Dickinson in 1890—adding titles, adjusting punctuation, and altering Dickinson’s language—and began a legacy of Dickinson edits. “The Sleeping Flowers” and “Morning” are now better known by their first lines, “Whose are the little beds – I asked” (1859) and “Will there really be a ‘morning’” (1860), respectively. For more on St. Nicholas and the edited Dickinson poems, see Ingrid Satelmajer, “Dickinson as Child’s Fare: The Author Served up in ‘St. Nicholas,’” Book History 5 (2002): 105-142.

[3] Satelmajer, 106. Satelmajer cites nineteenth-century periodical scholars Richard Ohmann, Politics of Letters (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1987); Michael Lund, America’s Continuing Story: An Introduction to Serial Fiction, 1850-1900 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1993; and Ellen Gruber Garvey, The Adman in the Parlor: Magazines and the Gendering of Consumer Culture, 1800s to 1910s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). See also Kenneth M. Price and Susan Belasco Smith, Periodical Literature in Nineteenth-Century America (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992).

[4] While other children’s and young reader’s Dickinson-oriented books are available, for the sake of space I have selected these texts because they center Dickinson’s poetry, not her life story. For contemporary kid-oriented Dickinson biographies, see Michael Bedard’s Emily (New York: Doubleday Book for Young Readers, 1992), Jennifer Berne’s On Wings of Words: The Extraordinary Life of Emily Dickinson (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2020), and Jane Yolen’s Emily Writes: Emily Dickinson and Her Poetic Beginnings (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2020). Dickinson herself wrote poems for her favorite young nephew, Thomas Gilbert (Gib) Dickinson (1875-1883); here I focus on poems scholars and editors deem “for kids.”

[5] I’m Nobody! Who are You?: Poems of Emily Dickinson for Young People (Owings Mill, MD: Stemmer House, 1978).

[6] Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus, “Surface Reading: An Introduction.” Representations 108, no. 1 (2009), 9.

[7] Best and Marcus, 5.

[8] Frederic Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (Ithica: Cornell University Press: 1981), 48.

[9] Best and Marcus, 4. Best and Marcus cite what Paul Ricoeur labelled a “hermeneutics of suspicion” in Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation, trans. by Denis Savage (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970).

[10] In this essay I do not intend to dismiss these clear arguments for the benefits of “suspicious reading.”

[11] Best and Marcus, 9.

[12] Marcus also clarifies that her coinage, “just reading,” also recognizes all reading as interpretive: “even when attending to the givens of a text, we are always only—or just—constructing a reading.” Marcus, Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 73.

[13] Best and Marcus point to Susan Sontag’s important 1966 essay “Against Interpretation” and Sedgwick. Rita Felski’s The Limits of Critique (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015) also marks a more-recent contribution to the surface reading lineage.

[14] To offer a very abbreviated selection of further reading about these respective topics, see, for example, Richard B. Sewall, The Life of Emily Dickinson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998); Lena Christensen, Editing Emily Dickinson (New York: Routledge, 2007); and Nicole Panizza and Trisha Kannan (eds.), The Language of Emily Dickinson (Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press, 2021).

[15] Published in 1995, Werner does not speak of her methodology as surface reading explicitly, though she does speak of Dickinson’s “surfaces of writing,” and her description of her project parallels archival surface reading aims: “By providing facsimiles of forty of Dickinson’s late manuscripts along with typed transcriptions that display as fully as possible her compositional process, I hope to reveal the spectacular complexity of the textual situation circa 1870, which has been all but erased by the editorial interventions and print conventions of the present century” (1-2). Werner rather contends for “an aesthetics of open-endedness” (2). Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios: Scenes of Reading, Surfaces of Writing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995). Werner follows similar Dickinson projects by Sharon Cameron in Choosing Not Choosing: Dickinson’s Fascicles (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). See also Werner and Jen Bervin’s Emily Dickinson: The Gorgeous Nothings (New York, NY: New Directions, 2013), which is the first full-color coffee-table size publication of Dickinson’s “envelope poems.”

[16] Domhnall Mitchell, “The Grammar of Ornament: Emily Dickinson’s Manuscripts and Their Meanings.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 55, no. 4 (2001), 514. Emphasis in original.

[17] Mitchell, 513-4.

[18] Peter Hunt, “Introduction,” Understanding Children’s Literature, 2nd ed., edited by Peter Hunt (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 10.

[19] A product of its Puritan culture, The New England Primer too reflects and inculcates adult views of children, namely as sinners in need of redemption. As David H. Watters argues in his analysis of Primer’s biblical metaphors and allusions, “By learning a set of religious metaphors, the child learns about his or her place in the world.” Watters, “‘I Spake as a Child’: Authority, Metaphor and ‘The New-England Primer.’” Early American Literature 20, no. 3 (1985): 194. See also Kyle B. Roberts, “Rethinking the New-England Primer.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 104, no. 4 (2010): 489–523.

[20] For more on the development ideological, social, and material structures of childhood, see for example, Karin Calvert, Children in the House: The Material Culture of Early Childhood, 1600-1900 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992) and Hugh Cunningham, Children and Childhood in Western Society (New York: Routledge, 2005). For more on nineteenth-century children’s literature, see, for example, Anne Scott MacLeod, American Childhood: Essays on Children’s Literature of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Atlanta: University of Georgia Press, 1995); Beverly Lyon Clark, Kiddie Lit: The Cultural Construction of Children’s Literature in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005); James Holt McGavran (ed.) Romanticism and Children’s Literature in Nineteenth-Century England (Atlanta: University of Georgia Press, 2009); and Jessica L. Straley Evolution and Imagination in Victorian Children’s Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

[21] There is a large body of research on children’s engagement with poetry in the classroom that documents how poetry stimulates symbolic thinking and creativity in the individual For recent summaries of child poetic literacy research ranging from 1970 to present, see Krystyna Nowak-Fabrykowski, “The Role of Poetry and Stories of Young Children in their Process of Learning,” Journal of Instructional Psychology 27, no. 1 (2000); and Karen Coats, “The Meaning of Children’s Poetry: A Cognitive Approach” International Research in Children’s Literature 6, no. 2 (2016): 127–142.

[22] Hong-Nguyen (Gwen) Nguyen, “The Social Nature of Reading Poetry: The Case of Reading Haiku for Content,” Journal of Pedagogical Research 4, no. 3, (2020): 387–400.

[23] Catherine Compton-Lilly, “Building on What Children Bring: Cognitive and Sociocultural Approaches to Teaching Literacy,” The Journal of Balanced Literacy Research and Instruction 1, no. 1 (2013), 1. Dominant socio-cultural literacy theories came to the forefront in the 1960s and continue to spur practical and theoretical child literacy research like Nguyen’s project. See Lev Vygotsky, Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978) and Thought and Language (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986); Marie M. Clay, Becoming Literate: The Construction of Inner Control (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann Press, 1991) and By Different Paths to Common Outcomes (Grandview Heights, OH: Stenhouse Publishers, 1998); Ure Bronfenbrenner, The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979) and Bronfenbrenner and Pamela A. Morris, “The Bioecological Model of Human Development” in Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed., ed. R. M. Lerner and W. Damon (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006): 793–828. For a useful summary of theories of childhood literacy, see Christine Pegorraro, et. al. Early Childhood Literacy: Engaging and Empowering Emergent Readers and Writers, Birth – Age 5 (The Virtual Library of Virginia, 2021).

[24] Nguyen, 387.

[25] David Rudd, “Theorising and Theories: How does children’s literature exist?” Understanding Children’s Literature, second ed. ed. by Peter Hunt (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 15.

[26] Donald Hall, Oxford Book of Children’s Verse in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), xxxiv. The eight poems Hall includes are “A bird came down the walk,” “I like to see it lap the miles,” “I’m nobody, who are you?” “The morns are meeker than they were,” “A narrow fellow in the grass,” “There is no frigate like a book,” “To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee,” and “Will there really be a morning?”

[27] Hall, xxxiv.

[28] Hall, xxiv.

[29] Book jacket of I’m Nobody! Who Are You?, i.

[30] Nodelman continues to explain that because images take up the most space, “the texts these pictures accompany are also unique— unlike all other narrative texts. […] They are always dependent upon the accompanying pictures for their specific meaning and import; they often sound more like plot summaries than like the actual words of a story. Because the words and the pictures in picture books both define and amplify each other, neither is as open-ended as either would be on its own.” Perry Nodelman, Words about Pictures: Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 6.

[31] Poetry for Young People: Emily Dickinson, ed. by Francis Schoonmaker Bolin (New York: Sterling, 1994).

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] In 1969, scholar Dolores Dyer Lucas identified Dickinson with the English riddle tradition—a lens that Anthony Hecht takes up again in 1978. See Lucas Emily Dickinson and Riddle (Northern Illinois University Press, 1969) and Hecht, “The Riddles of Emily Dickinson.” New England Review (1978-1982) 1, no. 1 (1978): 1–24.

[35] I’m Nobody! Who Are You?, i.

[36] Stanley Plumly, “Wings.” The Kenyon Review 36, no. 3 (2014), 167-168.

[37] Dickinson, “A Bird came down the Walk,” The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition, ed. R. W. Franklin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999): 163, 1-4.

[38] Dickinson, 14.

[39] John Felstiner, “‘Earth’s Most Graphic Transaction’: The Syllables of Emily Dickinson.” The American Poetry Review 36, no. 2 (2007), 8. For a more-recent analysis, see Onno Oerlemans, “The Individual Animal in Poetry,” Poetry and Animals: Blurring Boundaries with the Human (Columbia University Press, 2018): 129-130.

[40] Richard E. Brantley’s comprehensive survey of critical interpretations in “The Empirical Imagination of Emily Dickinson,” The Wordsworth Circle 32, no. 3 (2001), 146.

[41] Emily Dickinson, “A Bird came down the Walk,” The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition, ed. R. W. Franklin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999): 163, 1-4.

[42] Poetry for Kids: Emily Dickinson, ed. by Susan Snively (Lake Forest, CA: MoonDance Press, 2016), 11; 1-4.

[43] For more on Dickinson’s novel punctuation, spelling, and spacing, see Willis J. Buckingham, “Emily Dickinson’s ‘Lone Orthography.’” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 75, no. 4 (1981): 419–35.

[44] Nancy Walker, “Emily Dickinson and the Self: Humor as Identity.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 2, no. 1 (1983), 59.

[45] Poetry for Young People: Emily Dickinson, 33.

[46] Dickinson, 8.

[47] Dickinson, 14-20.

[48] Felstiner, 8.

[49] Jennifer Adams, The Classic BabyLit Collection (Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 2018).

[50] The BabyLit “Storybook” line for 3-5 year-old readers includes The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Moby-Dick, The Jungle Book, and Little Women. https://gibbs-smith.com/collections/babylit-storybooks

[51] Emily Dickinson, “A sepal, petal, and a thorn,” qtd. in Kate Coombs, Little Poet Emily Dickinson: In Emily’s Garden (Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 2019), 8.

[52] Beverly Lyon Clark, “BabyLit to Lusty Little Women: Age, Race, and Sexuality in Recent Little Women Spinoffs, Women’s Studies 48, no. 4 (2019), 436, 435.

[53] I’m very sympathetic to Amazon reviewer Izak Contreras’s idealism, who quotes the script of Joe Wright’s 2005 Pride and Prejudice film to explain his feelings about the Classic Collection box set: “Completely[,] Perfectly and Incandescently Wonderful,” the reviewer says, “The future parents I gave them to were so excited about them.” I similarly have purchased three BabyLit books for three of my expecting friends. Izak Contreras, Review of The Classic Baby Lit Collection Boxed Set by Jennifer Adams (Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 2018), August 13, 2022. https://www.amazon.com/gp/customer-reviews/R2N750BK8JPCV8/ref=cm_cr_dp_d_rvw_ttl?ie=UTF8&ASIN=1423645731

[54] Suzanne Gibbs Taylor, qtd. in Julie Bosman, “A Library of Classics, Edited for the Teething Set,” New York Times (New York, NY), Oct. 26, 2013.

[55] Julie Bosman, “A Library of Classics, Edited for the Teething Set,” New York Times (New York, NY), Oct. 26, 2013.

[56] Carolyn Foster Segal, “Oh, Baby(Lit),” Inside Higher Ed, last modified Nov. 20, 2013, https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2013/11/21/assessing-new-baby-board-book-empire-essay

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid.

[59] “Cozy Classics,” founded by Jack and Holman Wang, include The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Pride and Prejudice, Moby Dick, War & Peace, The Nutcracker, Les Miserables, Emma, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Jane Eyre, and Oliver Twist. “Classic Starts,” written for children 7+, includes Little Women, Sherlock Holmes, The Jungle Book, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, The Adventures of Robin Hood, The War of the Worlds, Gulliver’s Travels, Oliver Twist, A Little Princess, The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dracula, Arabian Nights, White Fang, Greek Myth, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Phantom of the Opera and many others.