Tim Chandler

Tim Chandler is a writer and art historian who is currently a PhD student in Art History at Concordia University in Montreal. His research investigates how failure was used as a narrative device in 19th-century art writing to communicate avant-gardeness. Prior to Concordia, he worked at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery as the TD Curator of Education Fellow from 2016 to 2018. He completed his Master’s in Art History and Visual Culture at the University of Guelph in 2016. His research is supported by a SSHRC Doctoral Fellowship.

Composing Annie Pootoogook:

Tropes and Inequity in Post/Neocolonial Biography

Note: An optional aural accompaniment to this paper is the 2015 collaboration between Iqaluktuuttiaq singer Tanya Tagaq and Toronto hardcore punk band Fucked Up, “Our Own Blood.” The thirty-minute piece, which consists of Tagaq performing throat singing over improvisations by Fucked Up, is an example of collaborative creativity through genuine reconciliation efforts. See Appendix.

Looking across the field of contemporary art, we find striking differences in the representation of artists in scholarly genres, popular genres, and genres in between – like art magazines. Art magazines, such as Canadian Art, C Magazine, and Esse, are not quite popular sources, but they, like newspapers, are written for mass audiences and have a wide readership. These magazines feature a wide variety of genres, from short news stories to longer considerations of exhibitions. Though publications are rooted in reporting and reacting to current events in art, art criticism in these pages shapes the public’s perception of an artist as the primary accessible source to consume information about that artist’s life. This is especially true of contemporary minority artists, particularly Indigenous figures already at a cultural disadvantage. Though scholarly discussion of Indigenous artists has tried to remedy how Western studies handle these artists’ stories, the same cannot be said of popular media. A powerful recent example of this tension is how Canadian media outlets covered the life and death of Inuk illustrator Annie Pootoogook, who died on September 19, 2016.

Pootoogook’s death became a national news phenomenon replete with negative tropes about Indigenous peoples: most of Canada’s prominent media entities ran stories about how the artist had fallen from grace and was living on the streets of Ottawa selling her art before she drowned. Robert Everett-Green’s account in the Globe and Mail is illustrative, saying that ten years after winning the Sobey Art Award, “the innovative, hard-working artist at the center of that revolution was living rough in Ottawa, selling her drawings on the street and begging for beer money near a downtown liquor store.”[1] And Pootoogook was aware of this narrative surrounding her life, as communicated by one of her gallerists, Jason St. Laurent, in a conversation with Carol Off on the CBC Radio program As It Happens:

CO: I’m looking at some of the articles. There’s one from 2014, the headline was “Alcohol Idleness Still Battle Acclaimed Inuit Artist.” The next year, “Inuit Artist Back At Women’s Shelter While Work Displayed At Art Gallery.” So these are the articles that troubled her when she saw them in print?

JSL: Yes. And you know it’s hard to imagine these types of articles written on any other Canadian artist that’s struggling. But, when it comes to Indigenous artists, these types of very personal details make their way into articles.[3]

Both the radio host and the gallerist were aware of the tragic narrative of Pootoogook’s life and the effect this narrative had on the artist while she was still living. Both the public and the individual artist were keyed into the effects of popular art writing, illustrating a pernicious cycle of artistic performance and public perception exacerbated by Western tropes and assumptions.

The narrative of Pootoogook’s struggle with the pressures of the art world rapidly moved through the broader Canadian art world. At the time of Pootoogook’s death, I worked at the Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, which had put on a solo exhibition of her large pencil crayon drawings depicting contemporary life in Kinngait, Nunavut, in 2006. Several weeks after her death, one of my co-workers mentioned that there had been an immediate increase in interest in the exhibition catalogs for Pootoogook’s show, signaling Pootoogook’s death prompted a surge in attention among Toronto’s art patrons (primarily white and upper-class) because it meant a tragic event (that resulted from decades of institutional neglect by the Canadian government) was being consumed as cultural capital by cultural elites. Before this moment, interest in the catalogs was practically non-existent. Still, the possibility of Pootoogook being a sort of Inuit van Gogh-like figure as a tragic, tortured artist was the inciting incident to bring awareness to a broader white audience.

Annie Pootoogook was the first artist in Kinngait’s now-famous West Eskimo Print Co-Operative to achieve international fame. She was born into an artistic family in 1969, the granddaughter of the artist Pitseolak Ashoona, and had a childhood typical of Kinngait, digging clams, and camping.[3] She began her artistic training at the co-op with her relatives in 1997 after she completed high school and returned to her hometown from Iqaluit, learning by observing the elders of the co-op. Pootoogook was said to have developed rapidly, and her work began to circulate to the south of Canada via the distribution of Dorset Fine Arts and Fehely Fine Arts. This rise culminated in her winning the Sobey Art Award, Canada’s most prestigious art prize for young artists, in 2006 and then exhibiting extensively in the years after with the aforementioned show at The Power Plant and others at the Art Gallery of Ontario and documenta 12.[4]

Popular writing about Pootoogook from this period emphasized what the Canadian art press saw as a meteoric rise in the Western art world but also exhibited a colonialist view of Pootoogook’s work already developing in the way her work was exhibited, especially when it was situated next to childhood art by white artists. Reviewing the international contemporary art exhibition documenta 12 for C Magazine, Rosemary Heather criticized this curatorial choice of: “It is too bad that [curators] Buergel and Noack also chose to situate Pootoogook’s work close to the childhood drawings of Austrian artist Peter Friedl,” as “the juxtaposition betrays a colonialist view of the Inuit artist” as intellectually inferior.[5] A review of an exhibition of Pootoogook’s work at the Museum of the American Indian in New York in 2009 identifies an impasse in the curation of the artist’s work: on one hand, she is presented as an important contemporary Canadian artist, but on the other hand, exhibition texts and materials consistently emphasize the tragic parts of her biography.[6]

The presentation of Pootoogook as a crucial but tragic artist during her lifetime dovetails with how major news outlets presented her upon her death, as already noted above. What is curious though, is writing about the artist was scarce from her commercial peak in 2006-2009 until she died in 2016. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s news archive features stories on the Pootoogook winning the Sobey Art Award in 2006 and then stories about her death in 2016 and after, but nothing in between. Similarly, Canadian Art has several articles that include passing mentions of the artist but do not seriously discuss her. Canadian media only covered her when her life dovetailed with the West’s notions of how an Indigenous artist should act, succeeding on Western terms in 2006 and then suffering a tragic death. This perhaps makes sense for major news outlets, who will only write about an artist when something significant occurs, but why was there also no coverage of her career in between these two poles by art-specific publications?

These two conjunctures around Pootoogook as an artist – her winning the Sobey Art Award and her death – illustrate the problematic tropes that persist in popular Western art writing about Indigenous subjects: Indigenous artists are placed in a bind where they must either be Westernized successes or colonized failures. Annie Pootoogook’s biography, informed by the media’s response to her death, is a case of an artist being fit into the ‘Tragic Native’ character trope perpetuated in Western (settler) art writing. I argue that in contrast to the traditional understanding of the term as a single contained volume,[7] biography as a life narrative is better considered an amalgamation of many disparate sources, such as critical art reviews, newspaper articles, and website features. Even though the publication of traditional biographies continues, understanding artist biography as an assemblage of imperfect perspectives, tropes, and expectations is crucial to evaluating criticism and popular writing about Indigenous artists. Thus, to properly contextualize the writing about Annie Pootoogook, I will look to Indigenous neo- and postcolonial studies, art historiography, and linguistic studies to investigate how tropes shape our understanding. I will also turn to critical studies of how allies write about Indigenous artists, concluding that we need revolutionary and real-world actions to push against Western biography and tropes about Indigenous artists.

Indigenous Challenges to Postcolonialist Biography

In writing about colonialist tropes and biography about Annie Pootoogook’s life and death, I begin here with an extensive discussion of terminology to move towards a better approach to life writing about Indigenous artists. As a cisgender white man, it is important to clarify my use of language when speaking about a cultural group that, though often seen as homogenous through a Western lens, comprises many distinct cultures and populations. I will use the term Indigenous, as it is a term that encompasses the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people of Turtle Island.[8] I chose ‘Indigenous’ instead, as it has become the most common and accepted language used in academic settings and lived experience.[9] Still, to resist generalizations about a diverse group of peoples, beliefs, and social systems, ‘Indigenous’ will be used to address large-scale ideas of how European/Western writers and thinkers treat Indigenous peoples. Often, these writers group the Inuit with all of Turtle Island’s Indigenous Nations, despite the former being distinct from the latter. Cree-Métis-Saulteaux curator and art historian Jas M Morgan suggests that the Inuit are further marginalized within Indigenous academia.[10] To consider this shared knowledge from the Inuit, ‘Inuit’ will be used whenever possible to discuss Pootoogook and her artistic community, and ‘Indigenous’ only when referring to Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples as a whole.[11] It is also important to note that I am writing this paper through a Western lens and describing subjects in terms of how they relate to Canadian art historiography when the subjects are not Canadian.

The general sense of postcolonial studies, broadly defined by Edward Said in Orientalism as a method of inquiry questioning Western power in knowledge production after European countries colonialized the rest of the world, is also resisted by some Indigenous scholars, who view North America as a neocolonial environment rather than a postcolonial one.[12] Noted Ojibwe activist Winona LaDuke describes this distinction:

What masquerades as a postcolonial paradigm is often only a new form or new derivation of colonialism, with the attendant struggles of native peoples for the same things: to control our destiny, to control our lives, our land, and to continue our life ways in relative peace.[13]

It is easier for Western academics to view Turtle Island as a postcolonial place when in their view, they are no longer actively colonizing it. However, many Indigenous artists, such as Pootoogook, still suffer from the same oppression this population faced during the height of European colonization. Authors like LaDuke ask: What makes it different if this new postcolonial world perpetuates the same things as colonization? Still, Trépanier and Creighton conferred with 18 Indigenous scholars who disagree with the term “postcolonial” but agree with postcolonial scholarship’s general goals in critiquing the Western lens.[14] The two poles of ‘post-’ and ‘neo-‘ colonial studies establish a framework for settler art historians to approach contemporary Indigenous subjects.

This paper does not seek to answer those questions fully but does consider this point of view while examining Annie Pootoogook’s life as an example of neocolonial biography and teasing out the problems in settler writing about her. [15] Settlers who are aware of the neocolonial struggle that Indigenous peoples face often seek to identify as allies to their cause, which entails learning about anti-oppression frameworks and supporting those who are oppressed.[16] Many of those who wrote about Pootoogook after her death identified as allies to some degree, yet they still perpetuated harmful stereotypes about the community she came from. These pitfalls illustrate the post/neocolonial theoretical distinction: writers may think they are working towards reconciliation but, in fact, still conform to colonial points of view. To work against this, Western writers must be deliberate in their efforts to support Indigenous scholarship, and even then they will likely make mistakes. As Western art historians writing about Indigenous artists and objects, the goal should be to bring in Indigenous ways of writing history rather than trying to incorporate Indigenous subjects into our established practice of writing and teaching art history. Heather Igloliorte, one of the foremost Inuk art historians, and Carla Taunton frame this process as such:

[Writing Indigenous art history] entails a fundamental shift away from past practices rooted in Eurocentric discussions of Indigenous arts, and a mobilization of productive methodologies – both Indigenous and non-Indigenous – that honour and centre Indigenous ways of knowing and being.[17]

To take this quote into account, I make use of metahistorical techniques while also prioritizing the readings of Indigenous issues and rights offered by Indigenous historians, art historians, and activists. It is important to not consider these two views as oppositional poles but to look at the ways that the latter can inform the former to arrive at a new understanding.

The ideological distance between Western and Indigenous academic approaches to Postcolonialism raises more important questions about Canada’s recent reconciliation efforts.[18] Can this process be called reconciliation if those that the actions are designed to help are not benefitting? A Canada working towards reconciliation and making that work a substantial part of its national platform should aim to provide an art world in which Indigenous artists have the tools to succeed and build on that success in their communities.[19] Annie Pootoogook is an artist whose success should have put her in a position to be a beneficiary of the government’s reconciliation efforts, as she was a nationally recognized artist after winning the Sobey Art Award. Instead, she suffered under pressure from the Western art world and Canada’s systematic failings. Her death should be read as a product of those forces rather than an example of a stereotype.[20] Reconciliation in the arts failed Pootoogook, which raises questions about who reconciliation benefits.

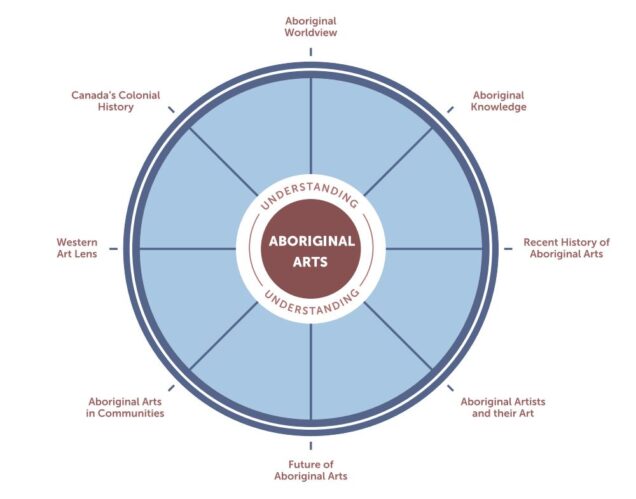

One of the ways that settler writers can contribute to improving the representation of Indigenous artists in media is to be critical of how Indigenous subjects have been written about in the past to avoid problematic depictions of marginalized peoples in the future. The first step in that process is to understand the various factors and perspectives contributing to contemporary understandings of Indigenous art. Trépanier and Chris Creighton Kelly’s report provides a broad framework for this (Fig. 1), and consulting the work of current Indigenous art historians, such as Igloliorte, Jolene Rickard, and Gerald McMaster, is a bare minimum second step. Many tropes about the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island are rooted in Eurocentric ways of writing and thinking embedded in Western art history, so dismantling them requires a conscious resistance to the ways that settlers have learned Indigenous art history. By knowing these tropes, how white writers use them, and where they come from, art historians can name them and work to make them less pervasive.[21]

Tropes in Historiography and How They Shape Our Reading

Attending to tropes plays a crucial role in historiographical analyses, providing a foothold for critics of art, literature, and film to compare and trace narrative, thematic, or character developments through time.[22] Tropes are more than clichés because they convey layers of meaning and allegory that direct the reader toward desired outcomes.[23] Assessing tropes is ultimately a historical practice, a core component of historian Hayden White’s historiographical work on tropes.[24] In working through the figurative structuring of historical texts through tropes, White uncovers how historians have used different storytelling methods, like tropes, to communicate large historical narratives. Doing so creates the history of the techniques used by the author and allows us to understand and critique the creation of that historiographical writing. The inverse of this is also true, and by writing a historiography of a specific type or example of literature, in this case, writing about Annie Pootoogook by the West, we can critique that process and isolate mistakes. This process is especially valuable in biography in its various forms, such as newspaper articles and magazine stories, as biography is a historical, social, and literary construction.[25]

White’s analysis of the tragic trope, in particular, helps us see how Western popular writers have subconsciously entrenched the tragic plot, fitting a history, life, or character into one of these modes allows us to quickly sketch where that text resides in a network of related texts.[26] As White summarizes, the tragic trope ends with the defeat of its protagonist, unjustified in their quest; this is the mode most applicable to how the West has written about Annie Pootoogook. Though some try to garner sympathy for the artist in how she died, the tragic circumstances of her death – the end of her story – are always emphasized.[27] To cite illustrative examples, in a segment for CBC’s The National, Deana Sumanac-Johnson concluded, “In recent years, Pootoogook was living on the streets of Ottawa, selling her drawings for a pittance.”[28] The Toronto Star’s Murray Whyte opened his review of that exhibition with an immediate mention of the circumstances of Pootoogook’s death, saying, “There’s a funereal air to Cutting Ice, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection’s exhibition of the late Inuit artist Annie Pootoogook. It’s not intentional, though, given the circumstances of her death, such a thing would be hard to avoid.”[29] This tragic emphasis on her death still grew Pootoogook’s name recognition, and she was the subject of a retrospective exhibition at one of Canada’s most prominent collections of art, The McMichael Gallery, and a book about her titled Carving Ice came shortly after that.[30] Her increased profile in south Canada is directly related to white interest in her tragic story.

Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz’s analysis of the artist figure as a recognized character in the public consciousness helps us further untangle the tragic tropes applied to Pootoogook by the popular media.[31] Kris and Kurz recognize that the public figure of ‘the artist’ is filled by a theory of what the artist is and does rather than the individual at a particular historical moment.[32] This trope of the “Tragic Artist” has its roots in the (largely white, largely Western) Romantic movement of the nineteenth century, seeing an artist’s premature death as a sign of genius cut short. The tragic artist figure was codified in the writing about modernism in the late-nineteenth century, especially as it pertained to the experiences of Manet submitting his work to the Paris Salon from 1863-1867 and then posthumous re-evaluations of Vincent van Gogh.[33] Failed artists had existed before this, but late-nineteenth-century Paris is the critical time and place where the stories of failed and tragic artists took off in art history and signified a quality of avant-gardeness in the artist. However, Indigenous and other minority artists who struggle or fail are nearly always ascribed negative tragic tropes and language, never idealized.

Western popular media’s coverage stands in contrast to the more thoughtful and respectful way that Indigenous writers handled Pootoogook’s legacy. In her obituary of the artist, Inuk art historian Heather Igloliorte does not mention the circumstances of Pootoogook’s death at all and instead focuses on the artist’s accolades and how she distinguished herself as an artist.[34] While being interviewed by Canadian Art and being asked a question about Pootoogook’s relation to the southern art market by a settler writer, Duane and Tanya Linklater were more forthright in how they planned to wrestle with Pootoogook’s biography, saying “We wanted to avoid certain tensions of those complications, and focus on giving the space that her work requires in this exhibition across the year. The year began with a reading of a text about Annie by Heather Igloliorte–she wrote an obituary, a beautiful text, for her.”[35] Each of these responses speaks a respect for Pootoogook’s experience and story and a level of caring for her legacy as an artist, to combat the historiographical modes that have plagued Indigenous peoples in North America.

In addition to challenging the Western monolithic artist image as a means of resisting colonialist tropes, challenging monolithic notions of biography helps us approach the artist in their full complexity. I propose the use of “biography” as not signaling to a single or specific text but to a loose, abstract understanding of the function of biography in art history and criticism.[36] An artist’s biography is a composite of the versions presented in traditional biographical novels, the “life and work” version presented in monographs, and from more scattered sources, such as critical reviews, newspapers, magazines, and interviews.[37] These varied sources are equally crucial in informing the public’s interpretation of an artist’s life. In this telling, biography is distributed among many sources rather than stemming from one definitive source, which differs from traditional Western ways of thinking about narratives.

The artist’s existence lies between these two poles of public life and private life. The public version of an artist is controlled and created entirely in a hive consciousness by the public. The latter part of the duality consists of the artist’s actual existence, which they can control. One part molds the matter, while the other is the matter, and tropes bridge the distance between them. These forces converge; separating an artist’s private and public versions is increasingly difficult. Since tropes are so entrenched in how we use language, we find them easy to understand because of their familiarity and how we have learned a language since we began speaking it. Linguist Raymond Gibbs’ understanding of tropes is that they represent the most entrenched ways humans use language that does not require special cognitive processes to understand.[38] We can fit the artist’s biography, as defined by Kris, Kurz, and Catherine Soussloff, and the historical modes of White into Gibbs’ linguistic framework, as they constitute some of the tropes of art history. The trope of the “Tragic Native” in popular culture is a new permutation of the older “Tragic Artist” trope from the nineteenth century but placed in a new ethnographic circumstance. Therefore, popular Western writers latch onto Pootoogook as the next ‘Tragic Native’ because the Western thinking process around language in art history has programmed us to understand it this way. This mode of thinking dehumanizes Pootoogook because it leads Western thinkers to associate her experience more as a representation of the ‘Indigenous’ experience in the art world rather than the story of one Inuk person experiencing systematic racism and the effects of a neo-colonial environment.

The White Savior Complex and Problems in Allyship

One of the problems with Canada’s recent reconciliation tactics is that the arrangement primarily benefits the state rather than those it is designed to help. The governments of postcolonial states make reconciliation with Indigenous Nations a significant part of their campaign and policy, as being an ally to these marginalized peoples is generally acknowledged as the right thing to do. However, Westerners advocating for reconciliation often do not recognize how deeply the ‘white savior’ complex permeates their efforts. Jas M. Morgan said that in focusing on the circumstances of Pootoogook’s death and emphasizing the tragedy of it, the Western media’s response “reeks of white savior complex.”[39] This white savior gaze toward Indigenous artists dehumanizes and exploits its subjects. It creates a romanticized version of Inuit artists that ignores the current state and issues regarding ongoing colonialism and surface-level reconciliation. This gaze has been a problem with Western writing about Indigenous peoples in general, and the romantic notion of who the peoples are and what they do results in Eurocentric tropes beyond that of the ‘Tragic Native’ dominating the text. Dakotan historian Philip J. Deloria writes:

how white Americans have used Indianness in creative self-shaping have continued to be pried apart from questions of inequality, the uneven workings of power, and the social setting in which Indians and non-Indians might actually meet.[40]

In the case of Annie Pootoogook, white writers present her death as if it happened in a far-off world, away from current Canadian metropolitan existence. They talk about her success earlier in her career and how far the circumstances of her death were from that success, but nothing in between these two episodes. The CBC article on her death opens by saying:

Prominent Inuk artist Annie Pootoogook has been identified as the woman whose body was found in Ottawa’s Rideau River earlier this week. Officials with the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in her hometown, Cape Dorset, Nunavut, confirmed the death of the chalk-and-ink artist, who rose to prominence when she won the Sobey Award in 2006. Pootoogook, 47, had been living in Ottawa.[41]

This narrative distance exists because filling in the space between those events would mean that the white writer, or their publisher, must confront the fact that our current social system and art economy contributed to her death.

Unfortunately, writing featuring stereotypes of Indigenous peoples will sell better commercially and be more easily published than writing that does not.[42] In their article “I is for Ignoble: Stereotyping Native Americans” for the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Arlene Hirschfelder and Paulette F. Molin outline how stereotypical images of Indigenous peoples persist in commercial goods and outsell more faithful depictions or reflections of Indigenous culture.[43] This speaks to how white settlers and even allies pigeonhole the experiences and representations of Indigenous peoples, including the Inuit. A white writer writing about Annie Pootoogook will subconsciously fit her into the mold of the writing they have already seen. “American Indians are richly diverse, yet all too often their public portrayals…are greatly at odds with actual Native peoples and cultures,”[44] so stereotyping Pootoogook as a tragic figure implies that the defining traits of the Inuit are drinking problems and early death. Western writers have extensively used tropes about Indigenous peoples since colonization, some being ‘the savage,’ ‘the warrior,’ and ‘the princess.’[45] The treatment of Pootoogook is just the following link in that chain.

Allyship and the white savior complex were heavily criticized by the Indigenous activist group Indigenous Action in their zine/pamphlet Accomplices, not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex, published in 2014. The group argues that allies often carry romantic notions of the oppressed groups they wish to help, which leads them to see the groups as victims rather than marginalized people.[46] This attitude also trickles down through the institutions, corporations, and organizations that the ally is involved with, and by placing importance on the actions themselves rather than those they are aiming to help, they reinforce the division that created this problem in the first place. Indigenous Action is especially critical of activists and non-profit organizations, referred to as ‘non-profit capitalists,’ which rely on their allyship for their careers.[47] To make their careers in activism work and commodify the struggle of marginalized peoples, they must first objectify that struggle. ‘Where struggle is commodity, allyship is currency.’[48]

As anyone who has watched an authority figure stumble through the pronunciations in a land acknowledgment can attest, this is a problem that is becoming more and more prevalent in Western institutions, as acknowledging reconciliation becomes an integral part of institutional programming, but acting on it remains the same as it ever was. The white savior and ally industrial complexes are forms of latent white supremacy and a reminder that those in positions of privilege must always be working to unlearn their attitudes toward marginalized groups. The white savior gaze is the ultimate result of ‘allies’ and the act of someone who is not committed to advancing Indigenous independence but does recognize the need to align themselves with that cause.

New Ways of Evaluating Indigenous Biography

In art history, one of the primary ways tropes influence our perception of artists is through the public figure of ‘the artist’ as discussed earlier in the work of Kris, Kurz, and Soussloff. The current value of what an art historian does is bring out knowledge by relocating an artwork in its historical matrix, closing the gap between past and present.[49] As a result, the artist is a streamlined, simplified figure meant to make it easy for an unspecialized or unfamiliar reader to understand what is essential or distinctive about the artist and where they exist in art history.

Critiquing popular media and its usage, or in this case, weaponization, is a historical process.[50] The process of the creation of the ‘Tragic Native’ trope and its development into the type that Western art history reads Annie Pootoogook’s character as is a historical one too. Pootoogook’s case is helpful because we saw the process in real-time: the white savior and ally industrial complex greatly influenced the writing about Pootoogook after her death. As soon as she died, writing about her death overwhelmed any other media about her, and her biography was diluted to be a fall from grace. Art magazines, newspapers, radio shows, and television all homed in on her death because that was the story they wanted to sell and what their audience was already used to hearing.

Suppose Annie Pootoogook was the most recognized Indigenous artist and the benefactor of reconciliation efforts in winning the Sobey Art Award. Why did she die the way she did? Why did she not benefit from her successes? The answer is that Indigenous artists are forced to overcome the authority of the Western art lens and reckon with the role and tropes that Western writers have assigned to Indigenous peoples to make their specific culture heard beyond the local.[51] The public has been trained to connect the writing about an artist to their artistic process, so for Indigenous artists to overcome the hegemony of the Western art media, they are also forced to reckon with the Western idea of an Indigenous, no matter how far from reality it may be. This conditioning creates a double bind for Indigenous artists, who are pushed towards exploiting their identity to succeed in the Western art world. Pootoogook was, understandably, unable to overcome this, resulting in her death.

Conclusion

Though the Western popular media of Pootoogook’s death is wrought with stereotypes, it is also unacceptable to ignore her death, as that results in ignoring the failing current state of reconciliation.[52] To ignore the circumstances of her death is to ignore the reality of the current art economy around Indigenous artists and the problems therein. This bind is especially evident in writing about Indigenous artists in a Neocolonial world. It is hard to know if there is a ‘right way’ for settlers to write about the failings of reconciliation. This dilemma is all the more obvious in comparing the way that Indigenous writers covered Pootoogook’s death, such as how Heather Igloliorte focused on the artist’s cultural impact and how Jas M. Morgan called to action to change our perception of Pootoogook in the future. The wide gap in the content about Pootoogook by settlers and Indigenous writers suggests that settlers are oblivious to large parts of the experience of living during reconciliation as an Indigenous person. This is necessary to rectify in the future. Indigenous Action argues that allyship is the corruption of radical thinking required to facilitate a tangible form of reconciliation.[53] Though none of those instrumental in creating the stereotype of Annie Pootoogook self-identified as radicals in thinking or political alignment, their labels as allies align them with radicals in some way. Ultimately, this is a helpful reminder that real change in the Western art economy, that would benefit Inuit artists and accomplish tangible acts of reconciliation, can only be achieved through revolutionary actions, ones with legal consequences and risk for its participants.[54] To confuse our interest in the well-being of Indigenous peoples with the fight for the preservation of Indigenous Nations is dangerous and ignores the brutal reality of the situation.

[1] Robert Everett-Green, ‘Annie Pootoogook: A life too short, built on creativity, but marred by despair,’ The Globe and Mail, last modified 12 November 2017, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/art-and-architecture/the-remarkable-life-of-inuit-artist-anniepootoogook/article32198919/.

[2] CBC Radio, ‘Stereotypes plagued Inuk artist Annie Pootoogook in life as in death, says gallerist’, last modified 29 September 2016, https://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/as-it-happens-monday-edition-1.3779380/stereotypes-plagued-inuk-artist-annie-pootoogook-in-life-as-in-death-says-gallerist-1.3782623.

[3] Nancy Campbell, Annie Pootoogook: Life and Work (Toronto: Art Institute of Canada, 2020): 5.

[4] ‘Annie Pootoogook’, Feheley Fine Arts, accessed May 10th, 2020, https://feheleyfinearts.com/artists/annie-pootoogook/.

[5] Rosemary Heather, “documenta 12,” C Magazine, No 95 1 March 2006: 26-27.

[6] Leah Modigliani, “Annie Pootoogook’s Drawings of Contemporary Inuit Life,” C Magazine No 103 1 Sep 2009: 47-48. “The lack of curatorial intervention in Pootoogook’s work suggests questions somewhat harder to pinpoint or resolve. On the one hand, her inclusion in Documenta 12, her winning the 2006 Sobey Art Award and her invitation to participate in international artist residencies suggests that her work be considered simply as that of a contemporary artist from a culturally rich region of northern Canada. On the other hand, the texts and biographical videos about her work consistently emphasize her direct drawing style (“I draw what I see”) and her identity as an Inuit woman who has been abused but who has triumphed personally through her work as an artist. As a result, the formal and conceptual aspects of Pootoogook’s work are simultaneously protected from critique and elided in favour of a general enthusiasm for her personal story of artistic triumph.”

[7] “A written account of the life of an individual, esp. a historical or public figure; (also) a brief profile of a person’s life or work.” Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “biography, n., sense 1”, July 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1120962910.

[8] France Trépanier and Chris Creighton-Kelly, Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today: A Knowledge and Literature Review, Research and Evaluation Section, Canada Council for the Arts, 2011: 9. France Trépanier and Chris Creighton-Kelly approached the topic similarly in a report given to the Canada Council of the Arts by using the term ‘Aboriginal’ to refer to this cultural group.

[9] “Indigenous or Aboriginal,” Indigenous Corporate Training, accessed July 27th, 2023. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/indigenous-or-aboriginal-which-is-correct. Indigenous Corporate Training is an Indigenous-led organization designed to provide education about language use with regards to Indigenous peoples to large groups.

[10] Jas M Morgan, ‘Stories Not Told,’ Canadian Art, Spring 2017, https://canadianart.ca/essays/stories-not-told-annie-pootoogook/.

[11] Trépanier and Creighton-Kelly, Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today, 44.

[12] Edward Said, Orientalism, New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

Trépanier and Creighton-Kelly, Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today, 44-45.

[13] Winona LaDuke, ‘Foreword,’ in At the Risk of Being Heard: Identity, Indigenous Rights, and Postcolonial States, ed. Bartholomew Dean and Jerome M. Levi, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998, ix-x.

[14] Trépanier and Creighton-Kelly, Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today, 44-45. Much of this research project is a literature review designed to give a Western reader a broad sense of how Canadian writers write about Indigenous arts. Here they give 18 individuals who support this point.

[15] It is also necessary to define my use of the term ‘biography,’ as it differs from the literal sense of the term. In art historiography, I see biography as something dispersed through various kinds of media and an amalgam of sources rather than one source, as had traditionally been the case in art history in the nineteenth century.

[16] Indigenous Action, Accomplices, not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex, 2014: 1-2.

[17] Heather Igloliorte and Carla Taunton, ‘Continuities Between Eras: Indigenous Art Histories’, RACAR: revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 42, no. 2, 2017, 6.

[18] Reconciliation refers to how the government of Canada uses the term and reflects broad, national policies aimed at resolving the country’s relationship with its Indigenous population.

[19] ‘Reconciliation’, Government of Canada, last modified 9 April 2019, https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1400782178444/1529183710887; ‘Trudeau presents plan to restore Canada’s relationship with Aboriginal peoples,’ Liberal Party of Canada, last modified 7 July, 2015, https://www.liberal.ca/trudeau-presents-plan-to-restore-canadas-relationship-with-aboriginal-peoples/. This webpage documents Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s campaign promises regarding improved reconciliation during the 2015 federal election that he eventually won.

[20] Nancy Campbell, ‘Cracking the Glass Ceiling: Contemporary Inuit Drawing,’ PhD diss., York University, 2017, 52-55.

[21] A standard theory regarding the study of tropes is that once a trope has been named or discussed, it stops being as pervasive as it once was, moving from an unconscious tendency to a knowing metatextual device. An example of this discussion in popular culture would be the Simpsons episode ‘The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show’ from the television show’s eighth season.

[22] James Monaco, How to Read a Film: The Art, Technology, Language, History, and Theory of Film and Media (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981): 140; Johannes Ehrat, Cinema and Semiotic: Peirce and Film Aesthetics, Narration, and Representation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005): 441. This reading of tropes grew from film studies, where the term means a visual “turn of phrase” as a sign to the viewer that brings new connotations to what they see.

[23] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1980): 77-86; Robert Doran, “Human, Formalism, and the Discourse of History,” in The Fiction of Narrative by Hayden White (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010): xvii-xix.

[24] Hayden White, ‘Ideology and Counterideology in Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism,’ in The Fiction of Narrative: Essays on History, Literature, and Theory, ed. Robert Doran, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, 248. White goes so far as to say that Frye’s seminal text in comparative literature is ultimately a philosophy of history.

[25] I fully elaborate on this concept in my master’s thesis, Engineering Failure: Measuring Historiographical Changes in Artist Biography, University of Guelph, 2016.

[26] Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973, 39-42.

[27] For more on how art historians have relied on biography when writing about women artists, see Angela Rosenthal, Angelica Kauffman: Art and Sensibility, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

[28] Deana Sumanac-Johnson, “Annie Pootoogook, award-winning artist, dead,” The National, CBC News,

[29] Murray Whyte, “The death, and life, of Annie Pootoogook on vivid display at the McMichael gallery,” The Toronto Star, 16 September 2017, https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/visualarts/2017/09/16/the-death-and-life-of-annie-pootoogook-on-vivid-display-at-the-mcmichael-gallery.html.

[30] “Biography of Annie Pootoogook balances the good with the controversy, says author.”

[31] Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz, Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist: A Historical Experiment. Trans. Alastair Laing and Lottie M. Newman, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979; Catherine Soussloff, The Absolute Artist: The Historiography of a Concept, Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1997, 115. For them, this concept emerged in Early Modern Italy, and the two argue that as art historians, we should read biographies as collections of stereotypical stories and anecdotes, as it is this in the text which will reveal a culture’s understanding of the artist to us.

[32] Soussloff, The Absolute Artist, 112.

[33] The emergence, codification, and social, political and cultural implications of this trope are the subject of my current doctoral research.

[34] Heather Igloliorte, “Annie Pootoogook: 1969-2016,” Canadian Art, September 27, 2016. https://canadianart.ca/features/annie-pootoogook-1969-2016/.

[35] John Hampton, “Inside a Year-Long Experiment in Indigenous Institutional Critique,” Canadian Art, 2 May 2017. https://canadianart.ca/features/indigenous-institutional-critique-case-study-wood-land-school/

[36] This was the subject of my master’s thesis, Engineering Failure, University of Guelph, 2016. See Philip Sohm’s “Caravaggio’s Deaths,” Art Bulletin 84 3 (Sep 2002): 449-468, for a discussion of biography being a form of criticism.

[37] Alfred Gell, Art and Agency (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998): 221-251. This reading is influenced by Gell’s analysis of the artist’s oeuvre in the last chapter of this book, using Marcel Duchamp as his example.

[38] Raymond M. Gibbs, ‘Process and products in making sense of tropes’, in Metaphor and Thought, ed. Andrew Ortony, Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1993, 253-254. Gibbs gives examples of tropes in linguistics, such as metaphor, metonymy, sarcasm, and idioms. For example, the trope of metonymy occurs when something related to an entity signifies the entity as a whole. For example, ‘the crown,’ meaning the British monarchy, has been used so much that it is now understood to have that meaning and no longer requires elaboration. Though tropes seem as if they are flouting the rules of language, they have become shorthand for us in speeding through those rules for the sake of conciseness and to be evocative.

[39] Jas Morgan, ‘Stories Not Told.’

[40] Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998, 189–190.

[41] “Inuk artist Annie Pootoogook found dead in Ottawa,” CBC News, September 24th 2016, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/annie-pootoogook-obit-1.3776525.

[42] Hirschfelder and Molin, ‘I is for Ignoble: Stereotyping Native Americans,’ Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University, 22 February 2018. Hirschfelder and Molin’s article outlines how stereotypical images of Indigenous peoples persist in commercial goods.

[43] Hirschfelder and Molin, “I is for Ignoble

[44] Hirschfelder and Molin, ‘I is for Ignoble’.

[45] Hirschfelder and Molin, ‘I is for Ignoble’.

[46] Accomplices, not Allies, 2.

[47] Accomplices, not Allies, 1.

[48] Accomplices, not Allies, 1.

[49] Christopher S. Wood, A History of Art History, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019, 4.

[50] White, ‘Ideology and Counterideology in Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism,’ 248.

[51] Trépanier and Creighton-Kelly, Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today, 45.

[52] Nixon, ‘Stories Not Told.’

[53] Indigenous Action, Accomplices, not Allies, 7.

[54] For example, in 2020, the Wet’suwet’en Nation staged long-term protests against the Canadian government’s installation of an oil pipeline. This protest prompted showings of support across Turtle Island, including blockades of the Canadian Railway, and did much more to draw attention to the failings of reconciliation than recent government initiatives.

Appendix 1: Our Own Blood

“It’s for careful contemplation and we’d like you to take it from us.”

“Our Own Blood” by Tanya Tagaq, Mike Haliechuk, and Jonah Falco. Vocals by Tanya Tagaq. Guitars by Mike Haliechuk. Percussion by Jonah Falco. Synth by Mike Haliechuk. Design and Layout by Sandy Miranda and Michael Haliechuk. Published by Rats Love Music.