Karli Snyder

Karli Snyder is a second-year graduate student in the Art History department at the University of New Mexico. She received a bachelor’s degree in history with minors in medieval studies and art from UNM. Her area of thematic interests and studies is centered on late medieval European art history with a particular emphasis on the interdisciplinary studies of gender and feminism and their connection to material culture, textile arts, fashion, and their intersectionality with manuscript studies. She is interested in how textiles, an art form unto themselves, have been used to formulate cultural, gender, economic, and social identities globally. Her secondary fields of interest include museum studies, curatorial and archival practices, collections management, object interpretation, and conservation techniques.

Weaving Identity and Resistance in Colonial New Spain:

Colonization, Women, and Textile Art in Colonial Mexico

Traditional textile arts were a thriving component of indigenous societies in what would become 16th-century New Spain. As sources of artistic innovation and design and as a means of economic currency, traditional indigenous textile arts within various communities signified social status, wealth, and artistic ability. As producers, designers, sellers, and consumers of this art, women held the forefront of this critical trade and form of social and monetary currency long before the arrival of Europeans in the New World.[1] As a consequence of colonization, the identities of indigenous women became intertwined with the social changes brought about by European settlement. Many traditional arts and dress were regulated by laws established during the earliest years of the viceroyalty, first established and maintained under Hapsburg rule from 1535 to 1700, to control and standardize feminine behaviors. With the emergence of a new social identity, that of mestiza, textile productions garnered a more nuanced distinction as a hallmark of such a new colonial identity. Not only did traditional textile arts still produced in private homes take on an entirely new meaning in the colonial environment, but they also evaded regulation, exploitation, and one textile, in particular, would become the very garment ubiquitous to a new Mexican feminine identity, the rebozo. Examining how indigenous textile practices were viewed and appropriated by Europeans and how traditional textiles were technically produced, consumed, and regulated shows how women, in particular, used the rebozo to assert individuality and maintain cultural autonomy.

Indigenous Women’s Roles in Pre-Hispanic Textile Production

Indigenous communities of various ethnic identities and distinctive language families were the first groups to settle in present-day Central Mexico.[2] One of the final dominant groups to emerge in the late-Classical period, c. 900 to 1519 CE, was the Mexica (or Aztecs), known for their incredible craft skills, artistic productions, and assimilations of other cultural styles.[3] Their monumental architectural accomplishments and production of codices, sculptural works, bodily ornamentation, and textiles are a testament to their artisan culture. Within this social dynamic, women were viewed as artistic creators and purveyors of the textile arts overall.

The Spanish colonization of traditional Mexica territories in present-day Central Mexico, which began tentatively after 1521, significantly impacted all facets of indigenous life in the region.[4] Much of the extant information on pre-Conquest practices survive in the codices, or illustrated historical and mythical accounts of indigenous religious beliefs and life which were formatted as screen folded manuscripts, produced at the direction of the Spanish government and church administration. With establishing a system of domination, Spanish governance took on the role of a colonial model of hierarchy and control, one that was centered on the religious conversion of the indigenous population and focused on extracting resources as a lucrative source of income for the Spanish crown . The views of those individuals (and eventually their respective institutions) in power were that indigenous colonized peoples were lesser beings in comparison to Spanish nobility and church officials because they had no “true religion.”[5] Rather, indigenous belief systems were viewed as paganistic and lacked the European definition of “man” and “nature,” two decisively opposing concepts espoused by Europeans in the 16th century. Because of the European view of man as superior to nature, two developments within the colonial system could occur: resource exploitation would arise unabated, and divisions of lesser beings from superior ones could be firmly cemented into what modern terms like “racism” and “sexism” would come to define.[6] Upon initial colonization of the New World, indigenous peoples were themselves viewed as a resource to exploit. As noted by historian Andrés Reséndez, the indigenous populations in the Caribbean were significantly impacted by disease and enslavement and the Spanish crown passed laws granting all colonial natives legal standing and the promise of protection from forced labor to avert further population loss. This was not a technically enforced law, as is evident with the creation of the encomienda system, a forced means of agricultural tribute paid by natives to new recipients of Spanish land grants, typically members of the newly-titled nobility.[7]

As sources of resource documentation and references for future exploitations and extractions, the production of post-Conquest Colonial codices documented the extensive textile productions traditionally undertaken by Aztec women. With few extant Pre-conquest examples of the Mexica’s codices which documented their actual histories, cultural accounts, and social narratives, reliance on colonial-era codices has established a narrow view of indigenous life before the arrival of the Spanish.[8] Specifically, the scholarly emphasis of the various colonial codices and their depictions of indigenous cultures has often overlooked the symbolic nature of the role of women and textile productions.[9] A critical view of these codices asserts that indigenous artists produced these objects for a European audience and that the decorative program, which included imagery of indigenous religious practices and social traditions within them, fit easily into a masculine-centric Christian European narrative. This narrative was, as previously noted, one of a concretization of binary opposites such as us/them, man/woman, and Spanish/indigenous that further entrenched the development of racism and sexism within the colonial system.[10] The visual evidence of this binary opposition and the indigenous assimilation of many European figural styles is evident in the codices’ illustrations, which further implies that indigenous artists were creating the imagery for European viewing.[11]

Pre-Hispanic Mexica culture emphasized women as the keepers of the domestic realm, which meant that women were also the key producers of critical functional elements of life, including clothing and textile works.[12] Feminist scholar Susan Kellogg has written on gender parallelisms within Mexica society and how a binary construction of both male/female social and religious roles permeated everyday life in the Pre-Hispanic period.[13] This parallel is corroborated by the subsequent work of scholar Caroline Dodds Pennock, who concurs with Kellogg, as both argue that this inherent structure of power and social stratification did not create a true gender equilibrium but that Mexica women had far greater agency and held many roles and duties that created a complementarity within everyday life.[14] Within the social strata of Mexica culture, women were full citizens, sharing legal rights with their husbands and brothers, including claims to hold or inherit property, divorce, and appeal to legal courts in various proceedings. Both men and women could be appointed to and retain powerful social positions, such as merchants and marketplace overseers, traders, craftspeople, and educators.[15]

The more nuanced and symbolic nature of women’s roles in Mexica life was further implicated by the emphasis on their control of domestic spheres of the home and production of various goods (like textiles) for their family’s use and use as economic currencies.[16] Contrasting with the masculine-centered image of a patriarchal and warrior society, Mexica women held symbolic power within the domestic realm of everyday life, whereas men held the respective and parallel power of the political sphere.[17] This ideology did not preclude women from political influence however, as their functions within the realm of leadership were centered on the partnerships they held with men in positions of authority as their consorts, and they may have also fulfilled specific political responsibilities.[18] Women also held positions of authority in other public institutions, such as the marketplace, where they were both vendors and buyers of goods, and were also given positions as overseers who would determine fair market prices for merchandise, supervise the production of materials for war provisions, and assign tribute requirements to families.[19]

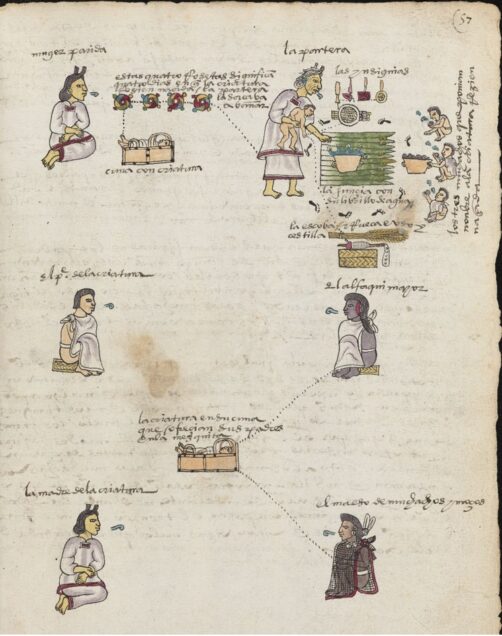

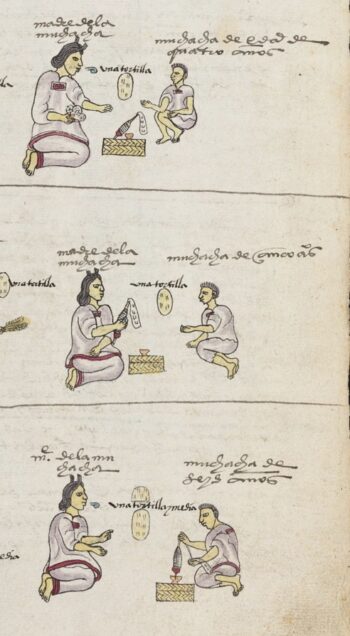

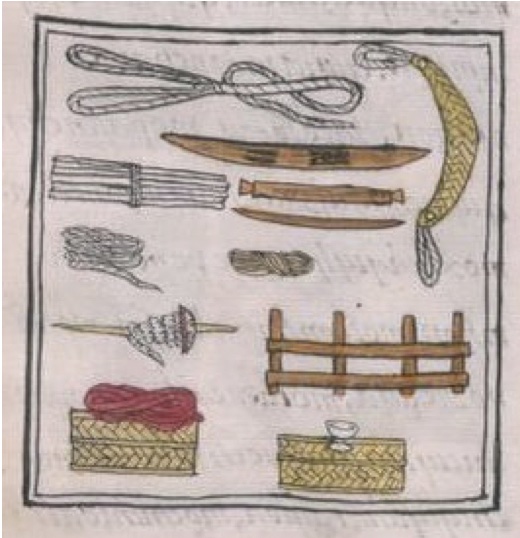

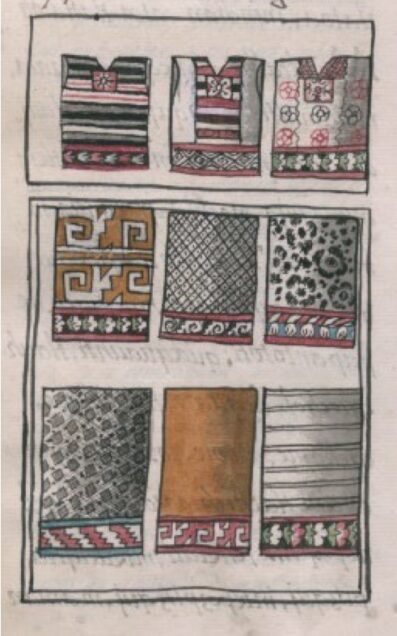

As related in several early colonial accounts, including the Codex Mendoza, when a girl was born, her umbilical cord was buried near the hearth of her family’s home. She was presented with her first set of miniature spinning and weaving tools during the completion of her purification and naming ceremony (fig. 1).[20] Furthermore, many scenes found in the Codex Mendoza and the Codex Florentine (more formally known as the Historia general de las Cosas de Nueva España, written by Fray Bernardino De Sahagún) provide detailed examples of the early lives of children and the Aztec approach to educating boys and girls alike.[21] In particular, scenes from the Codex Mendoza depict the education of young girls in the skill of spinning thread, which began at the age of 6 through 7 years old (fig. 2). By the age of 14, girls began to weave on a backstrap loom (fig. 3).[22] By the age of 15, girls were considered sexually mature and could then become partners and mothers, and their roles as caregivers and providers of domestic goods was solidified.[23] All women in Mexica society, from the lowest-class and impoverished groups to the noble and elite women in positions of relative power, participated in producing textiles for their domestic and religious uses.[24]

Depiction of the Purification and Naming Ceremonies of male and female infants.

A young girl is instructed by her mother on how to weave with a backstrap loom.

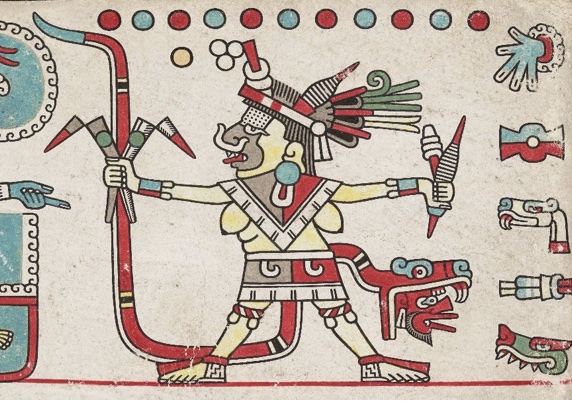

The symbolic nature of women and textile production was also a part of Mexica religion. Similar to the social aspects of their conquest of other neighboring indigenous groups, the Mexica absorbed and incorporated deities from other cultures they subordinated and exacted tribute from. Within the growing and complex Mexica pantheon of deities, several goddesses linked with women, and the production of textiles were vital components of ritual and religious life.[25] As anthropologists Sharisse and Geoffrey McCafferty discuss, the vast array of various female deities with attributes centered on the home, spinning, and weaving are too numerous to name definitively. Instead, many goddesses fit into a similar archetype with varying identities.[26] One such figure is that of Tlazolteotl, known as the “Great Spinner and Weaver,” and was associated with childbirth, the moon, menses, sexuality, witchcraft, healing, and purification. As one of few extant Pre-conquest Mexica codices, the Codex Laud or Codex Mictlan, a 15th– century screenfold codex, pictures Tlazolteotl and several of her associated rituals. She is most often portrayed wearing a headband of unspun cotton with cotton draped from her earspools and a spindle and whorl tucked into her headdress (fig. 4).[27]

Image of the goddess Tlazolteotl.

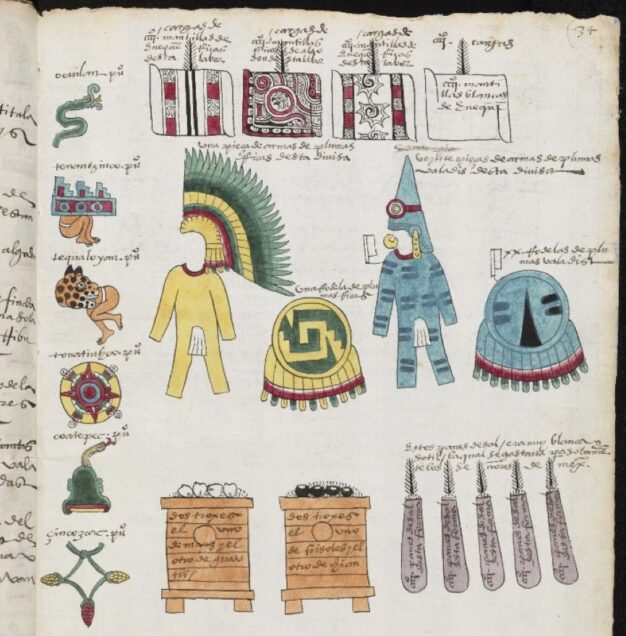

What is also documented in the codices and has been alluded to are the systems of taxation and tribute that the Mexica implemented within their own culture and the various other cultural groups they conquered. In order to support an economy based on a barter system and the exchange of products (whether agricultural or artisan produced) of equal values or uses, the Mexica exacted tributary payments from its lower classes of citizens and also from other subordinate groups.[28] Often these tribute payments were rendered in the form of foods, textiles, and specialized ritual garments, and the complexity of the tribute system itself is evident in sources like the Codex Mendoza, which delineates the quantities and types of items which were required and the locations of their sources (geographic regions and cultural groups).[29] Key to this system was the production of goods made by women, particularly woven textiles. As a source of economic currency and a required resource for the domestic sphere, the emphasis on women’s abilities to spin, weave, and create textiles was crucial in filling a niche monetary role. Particular tributary sources from various towns and outlying settlements were often prized for their artistic innovation, as sociologist Virginia Davis describes in her writings on the goods created in the town of Tenancingo, west of Tenochtitlan.[30] These textile products were documented in the upper portion of folio 34r of the Codex Mendoza and were noted for their stylized patterns and use of rich and contrasting colors (fig. 5). According to archaeologist Elizabeth Brumfiel, tribute cloth collected by official tax collectors called calpixqui, was paid by thirty-two of the thirty-four tax paying provinces of the Aztec empire, and between 147,000 and 428,000 items of cloth were sent to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan annually.[31] Women’s production of tribute cloth and clothing items was not accomplished without some resistance to the forced labor system under the Mexica. According to Brumfiel, not all forms of tribute cloth were high-quality, with some archaeological evidence providing examples of less carefully constructed clothing and poorly spun cloth. She notes this was not a widespread problem within the Mexica tribute system but was dependent upon the quality of production within various towns and Mexica-dominated community groups and was a direct correlation to coercive practices that women resisted through poor products.[32]

Pre-Colonial Textile Production Techniques

Because women produced such a vast number of various textile creations, they employed different methods of production and innovated components of dyeing and weaving that were highly individualized in terms of color, designs, and patterns based on the materials used. The two primary textile materials used were based on locally available plant products such as the processed fibers of the maguey plant, a type of agave, and cotton. In particular, the maguey plant was vital to the Mexica culture, and nearly every part of the plant was used in some manner. It was grown in thin soils and was drought and frost tolerant, both common climatic conditions in Central Mexico.[33] Multiple uses arose from maguey cultivation, including fermenting the beaten pulp into the alcoholic drink called octli or pulque and using the fibers spun into a hemp-like thread known for its hardy strength called ichtli.[34] Processing maguey fibers into thread was a lengthy undertaking. The leaves were cut from the plant and either beaten or buried in the ground inside an earthen oven for several days to loosen the flesh from the fibers. The remaining flesh was scraped away, leaving the fibers behind. The fibers are then washed and whitened with a heavy dough made of maize, at which point the fibers are ready to be spun. Even with its rugged qualities, maguey could often be further refined into threads as fine and soft as that of soft cotton, then woven and elaborately decorated.[35]

Despite its strength and utility, the Mexica considered maguey inferior to cotton, as several cotton varieties grew in the more temperate surrounding regions and were obtained by trade, barter, and tribute with other communities.[36] Processing the cotton fibers into thread was not as labor intensive as that of maguey, but its overall quality (either coarse or high-quality thread) depended on the species used and the number of processing steps.[37] Cotton had to be separated from the plant’s seeds by hand (ginned), cleaned, beaten, and combed before it was spun.[38] Spinning maguey fibers required a heavier set of tools, namely a weighted drop spindle whorl, while the lighter weight cotton fibers used a supported spindle instead (fig. 6). As an abundant archaeological source, spindle whorls, called malacates, were made of a range of materials from stone, seeds, wood, and fruit, but the best preserved and most often extant are made of baked clay.[39] Even spindle whorls could be highly decorative, often carved or fired with varying designs and insignias. The form of the spindle whorl itself (thread shaft) determines the speed and length of time that fiber will spin in a particular direction at a certain angle, which is a highly-developed technique that could create coarse to fine qualities of threads. The greater the diameter of the whorl, the longer it would take to spin, and therefore maguey fibers were typically spun using these larger whorls, which could be “dropped,” utilizing the weight of the whorl to create a tight spin and longer thread length. Because women could drop spin virtually anywhere, they were often seen walking to the market or the fields, with their hands busily drop-spinning as they traveled.[40] These public spinning practices were a vital component of women’s roles as domestic heads of households, with the need to create enough materials to render clothing for their families and themselves, as well as creating textiles in order to fulfill demands for tribute payments. Therefore, it is consistent with both the domestic and social demands for women’s labor that would make it an ordinary occurrence for women to use any available moments to process and spin thread.

Smaller spindle whorls were used for producing finer threads, and cotton was specifically spun, often using 0.5-inch diameter whorls, with the tip resting inside of a bowl to act as a catch for the instrument’s base. Extremely fine thread often incorporated bird feathers or metal wires into the thread to create a shimmering color effect in the light.[41] After the initial step of processing raw plant materials into spun fibers was completed, the application of dyeing techniques began. The use of dye materials, consisting of vegetable (annatto, tree barks, blackberries, brazilwood, and indigo), mineral (iron and iron oxide), and animal sources (cochineal and shellfish), were applied in methods typically termed resist- dyeing.[42] This technique implies that the spun materials were bundled and tied together, then placed in various colored dye baths to soak in the pigments. This method created an almost self-rendering pattern within the bundles of dyed strands where the areas of thread that had been tied together were void of color.[43] Resist dyeing, called plangi, became closely associated with specific weaving techniques, particularly those that incorporated the use of off-set weft threads within a warp design that had been previously created in the dyeing process.[44] For dyed threads that were not bundled to create a resist-dye pattern, an alternative use was made in vibrant embroideries rendered on completed garments.[45]

As the traditional loom of much of the Mesoamerican world, the backstrap loom was represented in images in both codices and further detailed in the Codex Florentine (fig. 7).[46] According to scholar Chloë Sayer, the development of the backstrap loom was just one example among many of the various indigenous resolutions to technical issues surrounding the weaving of textiles. In order to make weaving more time and energy-efficient, many advanced cultures created similar looms that supported the warp in a manner that divided the threads into two sets, allowing for a weft to pass through.[47] Because the loom was not structured on a rigid frame, it could be easily assembled and readily moved to any location. With the weight of the woman acting as the ballast and tension provider on the warp threads, and a pole or tree acting as the other end of the tension, the ease of a single individual using this loom was significant. This system allowed women to weave in any space, but mainly in the home, providing a sense of further control of the domestic sphere, as discussed earlier. Extraordinarily lengthy cloth could be woven on a backstrap loom, and pre-Hispanic textile practices did not allow for tailoring a finished product.[48] Instead, entire weavings were utilized as complete garments, creating the long, wrap-around skirts (pic) and squared blouses (huipils) worn by women (fig. 8).[49]

Just like their pantheon of deities, Mexica society was complex and based primarily upon a hierarchical schematic of ruling over the lower social class. The elite classes, whose ranks consisted of royalty, nobility, military and religious leaders, and scribes, were the recipients of the bulk of tribute items sent to the capital.[50] As alluded to in the previous mention of the maguey and cotton threads, cotton was reserved for use by elite Mexica society. Sumptuary laws were created and enforced by government officials, which allowed for clothing to encompass a signifier of elite social status.[51] Various garments, such as the huipil, were often richly embroidered (depending upon what class the wearer belonged to) with animal and plant motifs along the hems or the chest front. With examples of the elegance of the technical skills of pre- Hispanic textile practices, the colonial codices documented the products of women’s textile arts. Few, if any, extant textile objects remain from before the arrival of the Spanish or even the earliest Colonial period. This is due to various factors, including climate, difficulty preserving organic materials and their rapid deterioration, functional uses and subsequent wear, and the destruction of many objects during the Conquest.[52]

Colonization and Transformation

With the arrival of the Spanish in Central Mexico in 1521 and the subsequent establishment of the viceroyalty in 1535, colonization of what became New Spain by a dominant European force radically altered the culture of the Mexica and surrounding indigenous communities.[53] As the process of colonization took shape, all aspects of indigenous life were changed, and the implementation of colonial rule and its subsequent legislation created a new system of social, economic, and political norms. Not only did the Spanish create an entirely new religious and governing structure, but they also introduced new technologies, artistic mediums, and textile materials to the Americas, such as sheep’s wool, hemp, and flax for making linen, and silks and sericulture, as evident in the establishment of trade with Asia.[54] The environmental climate of Central Mexico was particularly favorable for growing hemp and flax seed varieties, and by the 1530s, both were being cultivated and processed into linen. Temperate climatic regions within Central Mexico were also conducive to growing mulberry trees, the sole food source of the silkworm and thriving sericulture began in colonial New Spain by 1536 with the importation of Asian silkworm larvae.[55] Components or entire quantities of ready-made materials needed to manufacture, produce, or consume goods came from multiple trade networks that extended from Spain and Europe to New Spain, Peru, and as far east as China, Japan, and Spanish colonial settlements in the Philippines.[56] As trade grew within these regions, an annual shipment of Asian goods arriving from the colonial port in Manila to the shores of western Mexico in Acapulco created an essential tie between Asian trade routes and the Spanish empire. The Manila Galleon, as this annual shipment was known, provided the critical link to luxury goods feeding ever-growing desires for their consumption in elite citizens in both Europe and New Spain.[57] With such a vast region exchanging materials and ideas, the influences of artistic styles in the production of textiles reached New Spain, and traditional forms of indigenous weaving were forever transformed.

A few examples of cultural exchanges in textile production are linked to the use of newly available luxury materials, such as silks and linen, and the further development of dyeing techniques from Asia called ikat (fig. 9). Silks were readily marketed and widely available in Asia. Once this material reached New Spain, it became easily obtainable in various city markets. This influx of cheaper raw silk also led to the gradual decline of previously established sericulture, which particularly impacted the economy of Murcia, the region where the most colonial Mexican-cultivated silks originated.[58] Ikat dyeing techniques from Asia were virtually identical to the long-used indigenous plangi styles, with the only exception being the amount of cloth dyed before weaving. Plangi techniques may have been gradually replaced by the newer ikat process as the 16th-century population decline of indigenous women continued. Davis describes this adoption of the Asian technique due to the loss of indigenous knowledge that was no longer available to later generations of textile producers.[59]

Accessed November 13, 2022. https://craftatlas.co/crafts/ikat.

Weaving and cloth production was further transformed by the eventual establishment of colonial textile workshops and the enforcement of sumptuary legislation and religious doctrines aimed at the lower classes of colonial society. As an example of an indigenous cultural parallel to Spanish society, all early colonial textile production was relegated to women, which was the same gendered practice in Europe until the introduction of global mercantilism and the rise of the workshop and guild systems in the 13th century.[60] Within Spanish social stratification, the opening decades of colonial life witnessed the diminished role of women in society, which easily justified the continued use of lower-class female labor in producing clothing and textile goods and harkens back to the emergence of sexism within the colonial system. This form of labor exploitation created yet another continuum of indigenous tribute practices.[61] As previously noted, not all indigenous women produced tribute cloth deemed acceptable, even when the Mexica tribute system was at the helm of this form of labor exploitation. The quality of tribute textiles further deteriorated once the Spanish took over the tribute payment system, and this further erosion could have been due to the reaction of indigenous women to “objective conditions of exploitation.”[62]

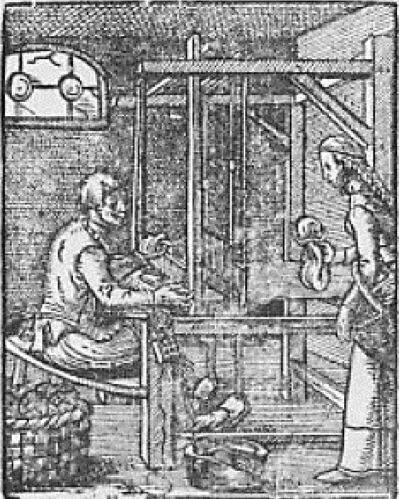

As the colonial economy and markets began to evolve, the Spanish re-interpretation of tribute was formalized within the encomienda (land grant) system with the establishment of workshops called obrajes. Just as guild systems in feudal Europe developed with mercantilism, the Spanish also formed gremios, or textiles guilds, to regulate the production of goods and train workers in how to utilize new technologies such as the foot-powered treadle loom (fig. 10).[63] The labor force needed to meet the growing demands for luxury goods among the colonial elites was fulfilled by the obrajes, with its primary labor source of lower-class indigenous women, as production levels rose by 17% compared to pre-Hispanic tribute records.[64] As a development in the mid- to late-colonial period, disease and harsh working conditions began to rapidly decimate the indigenous population. As a new source of labor, enslaved Africans were transported to New Spain and subjected to work in the obrajes that created goods for upper- and lower-class consumption.[65] This altered form of the previous pre-Hispanic tribute systems saw various resources, such as raw and manufactured goods and foods, paid to encomenderos instead of the traditional Mexica calpixqui.[66]

c. 1585. Collection of the German National Library, Frankfurt am Main.

Colonial Roles of Women

With the introduction of Spanish social norms and customs, the view of women’s roles in society shifted from their previously held positions with varying degrees of power in the pre- Hispanic period to that of European notions of gender roles and deferential status.[67] A significant element of the European view of feminine gender roles was relegated by the Catholic Church, the secondary seat of power in the colonial world.[68] A further aim of viceregal legislation was to assimilate indigenous men and women into what the Spanish viewed as an acceptable and civilized Christian society, which included more laws legislating attire. With Catholic religious practices enforced by the Church, men were required to cover more of their bodies, but the Church largely concluded that traditional women’s dress of the huipil and pic was modest enough. Colonial indigenous clothing styles are represented in an extant mid-17th century biombo folding screen, which depicts an indigenous wedding celebration with both men and women clothed in their best ceremonial dress (fig. 11). One new colonial directive was that women were required to cover their heads when they entered the sacred spaces of parish or cathedral churches.[69] The Church became a substitute for the Mexica temples as consumers of textile goods. It used similar religious and ideological dominion over women to amass clothing and textiles for the clergy, their almshouses, and hospitals, along with richly embroidered altar cloths and other liturgical textiles.[70]

Early colonial mass market production was centered on the processing and weaving of cotton, and Davis notes that cotton became a fiber relegated to the lower classes of society in New Spain. This new distinction was a direct result of the opening global trade market, the arrival of imported luxury goods, and the introduction of new materials such as silk and linen, which became widely available.[71] This new regulation also embodies what scholar Yolanda Fabiola Orquera describes as a generation of social differences and classification systems caused by “unequal conditions of access to the tools of cultural production.”[72] The emergence of unequal social systems was not just a consequence of the colonial power structure; it also enabled further racial and sexual classifications used “to justify economic and cultural dominion over the local population.”[73] Women’s labor was needed not just to fulfill the demands of the elite for luxury goods but also to clothe the majority of colonial society, such as the enslaved laborers, construction workers, and men employed in the gold and silver mines of Taxco and Michoacán.[74] Despite the implementation of workshops, an earlier 1549 edict made explicit the illegalization of “shutting up women in corrals, or elsewhere to spin and weave clothing that are to be given as tribute, and they shall have the freedom to do this in their houses so they will not be exploited.”[75] Although meant to spare indigenous women from the harshest forms of forced labor, this edict was utterly unenforceable, as many of the workshop’s textile mills continued production unabated at rapid paces.[76]

As a further consequence of the exponential increase in textile production and consumption, the Spanish government promulgated sumptuary laws as concerns grew over the ability to identify a person’s class and social status based on appearances. Not only were luxury materials more widely available across social classes, but the emergence of new social hierarchies also began with the intermarriage of Spanish, indigenous, and African peoples.[77] Questions over the purity of an individual’s bloodline consumed government officials, as the belief of close proximity to unadulterated Spanish descent was at the apex of the complex colonial social structure. The varying lower classes included the criollos (American-born Spaniards), the mestizos/mestizas, or offspring of Spanish and indigenous parents, and Africans at the lowest levels.[78] The establishment of this facet of the Spanish colonial power structure effectively created what postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha describes as “affective ambivalence,” or the formulation of self-identity of the dominant group/colonizer that is dependent upon the subordinate/Other.[79] Going beyond the simple binary formulation of Self/Other, as proposed by Edward Said’s Orientalism, theories surrounding postcolonial discourse, as conveyed by Bhabha, critique the formulation and identification of dominant and subordinate groups.[80] These crafted identities create mutual conditioning within each group, and the identification and subsequent appropriation of the Other are never wholly stable within the power structure, as evidenced by the Spanish need to regulate and control class behaviors.[81]

In an ironic parallel, Spanish sumptuary legislation was another continuum of indigenous social practices along with the colonial laws established to address class behaviors. An edict by the Royal Audiencia of New Spain, issued in 1582, forbade African, mulatto (Spanish and African mixed ancestry), and mestizo women from wearing any varieties of indigenous clothing and had to wear Spanish styles unless they were married to an indigenous man.[82] This edict was just one of many colonial laws promulgated and aimed at controlling women’s physical appearance. With the ability for members across classes to own some semblance of luxury goods, other laws aimed to control who could wear silks, jewels, and gold jewelry, most of which were typically reserved for the elite Spanish (peninsulares), criollos and indigenous nobility members (caciques).[83] As a facet of acculturation and a phenomenon of colonial society, many of the lowest class members of Africans, mestizos, and mulattos preferred to dress like indigenous men and women to manipulate identity and evade economic punishments such as taxes levied against non-native peoples.[84] Such cross-class behaviors provide further evidence of the instability of the Other’s identity.

Resistance and Colonial Identity

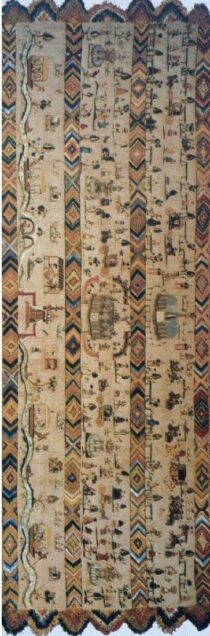

The majority of colonial scholars have written extensively on the establishment of the obrajes and gremios and have often neglected to focus on the role of indigenous women in producing textile art forms, which were transformed at the beginning of colonial rule in New Spain.[85] As artists whose early education was based almost entirely on textile skills, many indigenous women maintained what they could of traditional methods of cultural customs like textile production.[86] The forces of colonial laws, such as the 1582 Audiencia edict, and ensuing social transfigurations drove the need to adapt culturally significant and traditional textiles into new and innovative utilitarian objects. It also served to preserve some indigenous dress like the huipil and was most likely responsible for developing new mestizo garments, such as the ubiquitous rebozo, which “evolved to fill the vacuum that this social policy had created.”[87] Of somewhat nebulous origins, the long and rectangular rebozo (or shawl) that evolved during the early colonial period has become a ubiquitous identifier of contemporary Mexican feminine culture. A rebozo (from the Spanish word “rebozar,” or “to muffle up”) is most often intricately fringed on the ends and, depending on the class status of the wearer, could be made of maguey fibers or cotton dyed in ikat patterns. Towards the end of the colonial period, and as its popularity among women of all classes increased, it could be made of luxury silks interwoven with gold or silver threads and richly embroidered.[88] Dye patterns often mirrored the older traditional garments patterns depicted in the Codex Mendoza and the Codex Florentine. One of the most popular decorative styles, called paloma (Spanish for dove), was a white-speckled blue pattern, while other earth-tone colors and ikat dye patterns may be associated with the pre- Hispanic cult of the serpent, and its resemblance to the mottled patterning of a snake’s skin.[89] Specific patterns or design styles can also indicate a wearer’s regional identity. Each varying pattern, particularly in the earliest years of the rebozo’s development, would have been associated with a particular town, pueblo, or rural community. According to Davis, the earliest form of the rebozo may have originated in the town of Tenancingo, to the northeast of present- day Mexico City.[90] Tenancingo is still a center of rebozo production of exquisite craftsmanship today.[91]

Many theories of this garment’s origin have emerged since its popular rise as a cultural identifier. Sayer notes that it possibly evolved from the cape-like garment, the mantilla, that men wore. It may also have developed from the small square head cloths called rebozos that were used in Spain, or it was a descendant of the widely used indigenous carrying cloth called the ayatl (fig. 12).[92] Still other theories contend that the rebozo was an adaptation of South Asian garments, such as the ikat shawl known to be made and used by the Bagobo, an indigenous tribe from the Philippines, or even as a variation of the Indian sari.[93] These ideas would indeed correspond with the influential trade of the Manila Galleon. However, the anthropological knowledge of the rich textile traditions of the Mexica cannot be overlooked in the evolution of such a garment, and overall, the rebozo represents a truly syncretic cultural development.

With most indigenous and mixed-race women no longer able to consume specific luxury fabrics and materials, coinciding with the enforcement of colonial sumptuary laws, many sought a means of self-determination in something as innocuous as a utilitarian garment like the rebozo. Its multi-functional purposes serve not only as a head covering that was promulgated by the Church but as a barrier from the heat of the sun or cold weather, used as a way to carry and cover children, as an aid in childbirth, can act as an improvised basket for goods, as a kerchief for the face, as a way to protect food and other goods from the elements, and even as a death shroud.[94]

The rebozo could be made in the home using the traditional backstrap loom, while the obrajes operated as a parallel production system. Neither home nor obraje textile work was positioned in a competitive stance, as the backstrap loom represented the “home factory.”[95] However, this space of meaningful production was contained outside the realm of sanctioned work, and the colonial exploitation of women’s labor remained apart from the control women held over the domestic sphere, once again a parallel to the pre-Hispanic indigenous culture. Most utilitarian forms of the rebozo were woven with maguey or cotton threads and embellished using the newly adapted ikat dye methods (fig. 13).[96] More costly materials, such as silk, with lavish embroidery and fringing techniques could be used for rebozos that were made especially for women in the upper class (fig. 14 & 15). Individual women also specialized in particular components of the rebozo, as one may be skilled at the resist dyeing process, one at the actual weaving, and one on the addition of intricate fringe or embroidery.[97] Many luxury rebozos are still extant in various museums and private collections because of their selective uses in ceremonial or religious celebrations, as opposed to the utilitarian rebozos of lower-class women, whose use of these garments meant that wear would eventually lead to their demise.

Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, England.

It is not just that the rebozo was an essential and utilitarian innovation; it was also a means for colonial women, in particular mestiza women, to assert their autonomy by creating an item that was a visual symbol of heritage and gender identity produced outside the confines of the obraje system and colonial regulations. The rebozo became a hallmark of feminine identity, usually associated with women classified into various lower levels of the emerging elaborate caste system, or castas.[98] The rebozo is essentially a product of a colonial process that Bhabha describes as “mimicry.” According to Bhabha, mimicry is the process by which colonial power wrests from its subjects a representation of itself that is “almost the same but not quite,” with the difference being power, status, and knowledge held by the colonizers.[99] The colonized group’s response to this wrested misrepresentation is not just simple imitation (mimicry) but one that “emerges as the representation of a difference that is itself a process of disavowal.”[100] This comparison and the resulting mimetic reflections of the colonized are simultaneously a component of colonial identity and a source of its undoing.

The rebozo was a garment created to fill a void left by the colonial powers in its attempt to reinforce its self-identity, and ironically, towards the end of the colonial period, it became not just a symbol of lower-class women but of all colonial women. As depicted in a mid-18th century casta painting of a young morisca (the child of a Spanish father and African-European mother) and her child, the rebozo features prominently in the portrait, as the young mother is shown wearing the red and multi-colored striped garment over an oversized traditional African blouse (fig. 16). As previously noted, the popularity of the rebozo, as its development and use persisted through the colonial period, crossed all classes, with elite women commissioning their luxurious versions. In a stunning portrait of the early 18th century, the artist Juan Rodríguez Juárez painted the image of a beautiful young woman, most likely a member of the upper class, wearing a striped silken rebozo (fig. 17). Juárez depicted the garment with a shimmering and softly textured quality, as it drapes elegantly around the neck and shoulder of the woman.

The rebozo was a unique creation that combined the indigenous textile traditions with the influence of the global trade markets and existed within the spaces between colonial subjugation and prohibition. The origins of this colonial textile development are critical to understanding the thread of feminine production and identity in an overarching system before and after colonization, as it meant to appropriate and exploit women’s labor production. The rebozo became a means to fill a gap in the available clothing that women could wear, and in turn, counteracted and resisted colonial exploitation. Several factors coalesced for this garment to develop, including the influence of cultural exchanges that were an enormously critical component of the economy of New Spain. The enforcement of sumptuary laws and the establishment of the casta system further marginalized many indigenous and mestiza women, who sought a means to deter the neglect of individual skills and an assigned colonial identity with the creation and use of a garment like a rebozo.

[1] Sharisse D. McCafferty and Geoffrey G. McCafferty, “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity in Post-Classic Mexico,” in Textile Traditions of Mesoamerica and the Andes: An Anthology, ed. by Margot Blum Schevill, Janet Catherine Berlo, and Edward B. Dwyer (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 1996), 19.

[2] McCafferty, “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity,” 26.

[3] Chloë Sayer, Costumes of Mexico (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 1985), 28.

[4] Frances F. Berdan and Patricia Reiff Anawalt, The Essential Codex Mendoza (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997), xi-xiii.

[5] Walter D. Mignolo, “The Invention of the Human and the Three Pillars of the Colonial Matrix of Power: Racism, Sexism, and Nature,” in On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 158.

[6] Mignolo, “The Invention of the Human,” 159-160.

[7] Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016) 61-66.

[8] Davide Domenici, “Codex Mendoza and the Material Agency of Indigenous Artists in Early Colonial New Spain,” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 1, no. 2 (April 2, 2019): 107.

[9] McCafferty, “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity,” 21.

[10] Mignolo, “The Invention of the Human,” 159.

[11] Domenici, “Codex Mendoza and the Material Agency of Indigenous Artists,” 107-108.

[12] Berdan and Anawalt, Essential Codex Mendoza, Vol. 3, 145.

[13] Susan Kellogg, “The Woman’s Room: Some Aspects of Gender Relations in Tenochtitlan in the Late Pre- Hispanic Period.” Ethnohistory 42, no. 4 (October 1, 1995): 563–76.

[14] Caroline Dodds Pennock, “‘A Remarkably Patterned Life’: Domestic and Public in the Aztec Household City.” Gender & History 23, no. 3 (November 1, 2011): 529.

[15] Pennock, “A Remarkably Patterned Life,” 529.

[16] McCafferty, “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity,” 19.

[17] Pennock, “A Remarkably Patterned Life,” 530.

[18] Kellogg, “The Woman’s Room,” 565.

[19] Kellogg, “The Woman’s Room,” 566.

[20] Berdan and Anawalt, Essential Codex Mendoza, Vol. 4, 145.

[21] David Carrasco, “Women and children: weavers of life and precious necklaces.” In The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford Academic, 2013): 79-84.

[22] Berdan and Anawalt, Essential Codex Mendoza, Vol. 4, 120-125.

[23] Susan M. Strawn, “Hand Spinning and Cotton in the Aztec Empire, as Revealed by the Codex Mendoza,” in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings (Textile Society of American Symposium 2002, University of Nebraska – Lincoln, 2002), 8.

[24] Pennock, ‘A Remarkably Patterned Life,’ 529.

[25] McCafferty, “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity,” 26-30.

[26] Ibid, 26.

[27] Ibid, 26-27.

[28] Margaret A. Villanueva, “From Calpixqui to Corregidor: Appropriation of Women’s Cotton Textile Production in Early Colonial Mexico.” Latin American Perspectives 12, no. 1 (1985): 19.

[29] Berdan and Anawalt, Essential Codex Mendoza, Vol. 2, 48-49.

[30] Virginia Davis, “Resist Dyeing in Mexico: Comments on Its History, Significance, and Prevalence,” in Textile Traditions of Mesoamerica and the Andes: An Anthology, ed. Margot Blum Schevill, Janet Catherine Berlo, and Edward B. Dwyer (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), 310.

[31] Elizabeth M. Brumfiel, “Tribute Cloth Production and Compliance in Aztec and Colonial Mexico,” Museum Anthropology 21, no. 2 (1997): 57.

[32] Brumfiel, “Tribute Cloth Production and Compliance,” 55.

[33] Ibid, 55.

[34] Sharisse D. McCafferty and Geoffrey G. McCafferty, “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity in Post-Classic Mexico,” in Textile Traditions of Mesoamerica and the Andes: An Anthology, ed. Margot Blum Schevill, Janet Catherine Berlo, and Edward B. Dwyer (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), 19–44.

[35] Brumfiel, “Tribute Cloth Production and Compliance,” 55.

[36] Ibid, 55.

[37] McCafferty, “Spinning and Weaving,” 23.

[38] Annemarie Seiler-Baldinger, Textiles: A Classification of Techniques (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994): 2-4.

[39] Geoffrey McCafferty and Sharisse McCafferty, “Pregnant in the Dancing Place: Myths and Methods of Textile Production and Use,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs, ed. Deborah L. Nichols and Enrique Rodríguez-Alegría, vol. 1 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016), 376.

[40] McCafferty, “Pregnant in the Dancing Place,” 378-379.

[41] Ibid, 377.

[42] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 140-149.

[43] Seiler-Baldinger, Textiles: A Classification of Techniques, 148.

[44] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 62.

[45] Seiler-Baldinger, Textiles: A Classification of Techniques, 139-140.

[46] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 21-23.

[47] Ibid, 21.

[48] Ibid, 44-45.

[49] Linda Welters and Abby Lillethun, Fashion History: A Global View, Dress, Body, Culture (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2018): 86-87.

[50] Brumfiel, “Tribute Cloth Production and Compliance,” 56-57.

[51] Welters and Lillethun, Fashion History, 87.

[52] Elena Phipps, “The Iberian Globe: Textile Traditions and Trade in Latin America,” in Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, ed. Amelia Peck (London: Thames & Hudson, 2013), 31.

[53] Villanueva, “From Calpixqui to Corregidor,” 23.

[54] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 75-76.

[55] Phipps, “The Iberian Globe.” 39.

[56] Ibid, 32.

[57] Maya Stanfield-Mazzi, Clothing the New World Church : Liturgical Textiles of Spanish America, 1520– 1820 (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2021), 51-52.

[58] Stanfield-Mazzi, Clothing the New World Church, 21.

[59] Davis, “Resist Dyeing in Mexico,” 310-311.

[60] Welters and Lillethun, Fashion History, 87.

[61] Villanueva, “From Calpixqui to Corregidor,” 17-19.

[62] Brumfiel, “Tribute Cloth Production and Compliance,” 59.

[63] Villanueva, “From Calpixqui to Corregidor,” 18.

[64] Brumfiel, “Tribute Cloth Production and Compliance,” 65.

[65] Ibid, 65-66.

[66] Ibid, 57-58.

[67] Jonathan Truitt, “Courting Catholicism: Nahua Women and the Catholic Church in Colonial Mexico City,” Ethnohistory 57, no. 3 (June 1, 2010): 415.

[68] Truitt, “Courting Catholicism,” 416-417.

[69] Welters and Lillethun, Fashion History, 89.

[70] Villanueva, “From Calpixqui to Corregidor,” 24.

[71] Davis, “Resist Dyeing in Mexico,” 311-312.

[72] Yolanda Fabiola Orquera, “‘Race’ and ‘Class’ in the Spanish Colonies of America: A Dynamic Social Perception,” in Rereading the Black Legend: The Discourses of Religious and Racial Difference in the Renaissance Empires, ed. Margaret R. Greer, Walter D. Mignolo, and Maureen Quilligan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 168.

[73] Orquera, “‘Race’ and ‘Class’ in the Spanish Colonies,” 168.

[74] Villanueva, “From Calpixqui to Corregidor,” 23.

[75] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 76.

[76] Brumfiel, “Tribute Cloth Production and Compliance,” 65.

[77] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 91.

[78] Ana Paulina Gámez Martínez, “Painting and Dress in New Spain,” in Painted Cloth: Fashion and Ritual in Colonial Latin America, ed. Rosario I. Granados (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2022), 47.

[79] Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture, Routledge Classics (London: Routledge, 2004), 170.

[80] Arif Dirlik, “Placing Edward Said: Space Time and the Traveling Theorist,” in Edward Said and The Post- Colonial, ed. Bill Ashcroft and Hussein Kadhim (Huntington, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2001), 1–30.

[81] Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 133-134.

[82] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 91.

[83] Gámez Martínez, “Painting and Dress in New Spain,” 48-49.

[84] Ibid, 48.

[85] Villanueva, “From Calpixqui to Corregidor,” 18.

[86] McCafferty, “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity,” 20.

[87] Davis, “Resist Dyeing in Mexico,” 311.

[88] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 106.

[89] Ibid, 310.

[90] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 312.

[91] Emma Yanes, “Traditional Hands of Tenancingo.” Artes de Mexico, no. 90, El Rebozo (August 2008), 77- 79.

[92] Sayer, Costumes of Mexico, 106.

[93] Davis, “Resist Dyeing in Mexico,” 312.

[94] Ibid, 309.

[95] Ibid, 311.

[96] Ibid, 310.

[97] Yanes, “Traditional Hands of Tenancingo,” 77-79.

[98] Welters and Lillethun, Fashion History, 89.

[99] Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 127.

[100] Ibid, 122.