Genevieve (Genna) Kane

Genna Kane is currently a PhD Student at Boston University in the American & New England Studies Program. Genna researches twentieth century urban development, historic preservation, and public history. Her work emphasizes how historic preservation influenced urban planning, and the development of neighborhood identities through the built environment. Genna draws upon a background of public history and nonprofit management, which inspired her interest in the establishment and operation of historic sites. Genna plans to build off her research about historic sites as public history institutions to examine Boston’s built environment.

Retaining Maritime Life: The ICA’s Adaptive Reuse and Preservation of Industrial Heritage in East Boston

On July 4th 2018, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Boston opened their second exhibition space, called the “Watershed,” in Jeffries Point, East Boston. Instead of investing in a new building near their primary location in the Seaport district, the ICA decided to rehabilitate a condemned copper pipe warehouse in the middle of the East Boston marina. In a 2018 article about the project in the New York Times, reporter Hilarie Sheets wrote that ICA Executive Director Jill Medvedow “was describing the [East Boston] neighborhood when a young man interjected. ‘Maritime life is going away with everything coming into the shipyard,’ he said, somewhat confrontationally. The director quickly introduced herself — ‘I’m Jill from the ICA’ — and shook the hand of the man, who said his name was Dan. ‘I’m literally next door,’ he said. ‘Just thinking about my job, that’s all.’”[1] Dan’s concerns about the ICA in the marina highlight a ubiquitous fear that institutions such as art museums gentrify neighborhoods. Dan recognized that many parts of cities lose their character because real estate developers, institutions, or anyone with power will replace “unproductive” areas with buildings and structures that generate wealth.

Despite Dan’s concerns about the loss of maritime life, much of the East Boston marina already faced significant decay and lack of use. A creative strategy to rehabilitate decayed and unused structures is “adaptive reuse” – or altering historic buildings and/or infrastructure for new purposes. The former copper pipe warehouse necessitated significant rehabilitation, which the ICA achieved through combinations of reconstructing the decayed fabric, highlighting the historic fabric, and embracing the building’s historic program. The architects used newer industrial materials to blend the building into the existing marina. The strategy of adaptive reuse challenges the dominant narratives about real estate development and valuable history. Before the ICA’s project, historic preservation was not a viable option for the marina because the buildings decayed and the industrial history seemed unworthy of interpretation. Therefore, replacement or neglect were the only options for the marina’s buildings. However, the ICA’s investment in adaptive reuse broke the cycle of neglect in the East Boston marina while creatively interpreting the site’s industrial history. By closely examining the ICA’s vision and changes to the Watershed, this paper argues that the adaptive reuse of the copper pipe warehouse fought against the grain of trends in historical commemoration and against the grain of the process of architectural decay.

What do we do with former industrial sites?

The former copper pipe warehouse was established in the context of a productive shipping and industrial site in the East Boston harbor. The East Boston harbor thrived as a railroad depot and shipping port in the mid nineteenth century. Due to the success of the railroad industry, developers invested in land making to increase the size of the harbor.[2] As early as 1892, the Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad established a depot near the current location of the Watershed.[3] During World War II, ship production increased in demand, so the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Company established a dry dock near the Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad depots.[4] In 1955, the shipbuilding company constructed the copper pipe warehouse that would eventually become the Watershed. The warehouse functioned as an assembly and storage space for copper pipes and other materials used for constructing ships, which was the marina’s primary purpose in the mid twentieth century. The rest of the marina also resonated as a place of work. Ship builders and mariners may have lived in East Boston, but most of the marina’s surrounding neighborhood remained zoned for industry and business.[5] Historians characterized the marina as a place of constant movement – many migrants came to Boston through Jeffries Point, workers assembled and loaded ships the docks, but at the height of its productivity, few resided in Jeffries Point for long.[6]

The East Boston waterfront’s productive industry declined by the 1960s. Like many American cities, Boston’s deindustrialization rendered industrial sites obsolete. In Boston, government officials embraced urban renewal to replace the former railroads and industrial infrastructure in the center of the city with updated highways and luxury apartment complexes.[7] However, the East Boston waterfront remained relatively untouched in the 1960s and 70s, neither renewed nor maintained. By 1985, the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) obtained the East Boston harbor to aid the declining ship production on the waterfront. Instead of revitalizing the shipping industry however, Massport failed to make any improvements to the land.[8] Most of their resources remained invested in the neighboring Logan Airport, and the harbor in East Boston was not as “productive” as Massport anticipated.[9] By the late 1980s, Massport evicted boatmen from the East Boston piers.[10] However, Massport did not allow private developers to build on this land.[11] Instead, Massport held onto the marina until the City of Boston’s Housing Authority (BHA) developed part of the land on the waterfront for affordable apartments and middle-income condominiums in 2021.[12]

Both the general neglect of the harbor and Massport’s retention of the land resulted in gradual decay of the buildings at the waterfront. In addition to the rotting and condemned condition of the copper pipe warehouse before the ICA arrived, one prominent example of a building lost to decay in the neighborhood was the East Boston Immigration station. Sometimes referred to as “Boston’s Ellis Island,” the Immigration Station opened in 1920 and functioned as a processing facility for incoming immigrants until 1959. In 2010, the City of Boston Landmark Commission discussed whether the building warranted landmark status. The commission agreed that the history of immigration was essential to preserve, but they emphasized that “due to the deteriorated condition of the building, its lack of architectural integrity … the staff withholds recommendation to designate the East Boston Immigration Station as a Landmark.”[13] Due to Massport’s retention of the land and their unwillingness to maintain the waterfront, buildings like the Immigration Station rotted. The former copper pipe warehouse could have suffered a similar fate.

Perhaps earlier efforts for historic preservation could have reinvigorated the Immigration Station and its neighbors. Since the 1960s, the National Register of Historic Places recognizes thousands of historic buildings, and inscription on this list grants these buildings new purpose and vitality as museums or sites of historical interpretation.[14] However, the industrial buildings in the East Boston marina are unlikely to be considered landmarks because many buildings in the East Boston harbor are significantly decayed. As the Immigration Station demonstrates, if buildings lack integrity or the ability to demonstrate their historical significance, few preservation authorities will invest in them.[15] Unlike the Immigration Station however, the other buildings in the marina do not fit neatly into narratives of history that typically result in preservation. Many preserve buildings associated with historic heroes or significant chapters of history, such as historic house museums or birthplaces of significant historical figures. However, industrial history rarely has attributes that offer straightforward interpretation. As historians Marcus Binney, Ken Powell, and Francis Machin argue, “Enthusiasm for industrial architecture is a new phenomenon. Until very recently people have tended to judge industrial buildings by what they represent, rather than what they are. They have seemed to be unacceptable relics of oppressive working conditions and poor living standards.”[16] The combination of decayed buildings and lack of attention to industrial history suggests that typical historic preservation of the East Boston marina is unlikely.

Because preservation poses a challenge, the marina’s obsolete infrastructure seemed to pose two unappealing options: neglecting the buildings until dereliction, or replacing them with new facilities. These two avenues exemplify a narrative of architectural history that embraces progress. This narrative of progress contends that if there is no need for the industrial East Boston harbor, then it should be ignored until it can be replaced with new buildings. Architectural history students will recognize this narrative of history that emerged with the rise of modernism at the turn of the twentieth century. For example, architect Le Corbusier argued in 1923 that architecture should evolve. He wrote that “Civilizations advance… culture is the flowering of the effort to selection. Selection means rejection, pruning, cleansing; the clear and naked emergence of the Essential.” [17] Modernist thinking, and subsequently narratives of history as progress, suggest that architecture advances with civilization. In other words, buildings from the past with no contemporary use have no place in the built environment. Even though the destruction or replacement of historic buildings is by no means a new phenomenon, East Boston’s marina especially poses a challenge for heritage preservation. Embracing the narrative of progress for history not only praises certain stories over others, but this narrative also risks the loss of the buildings that contained a significant chapter of Boston’s history.

The ICA’s Vision for the Watershed

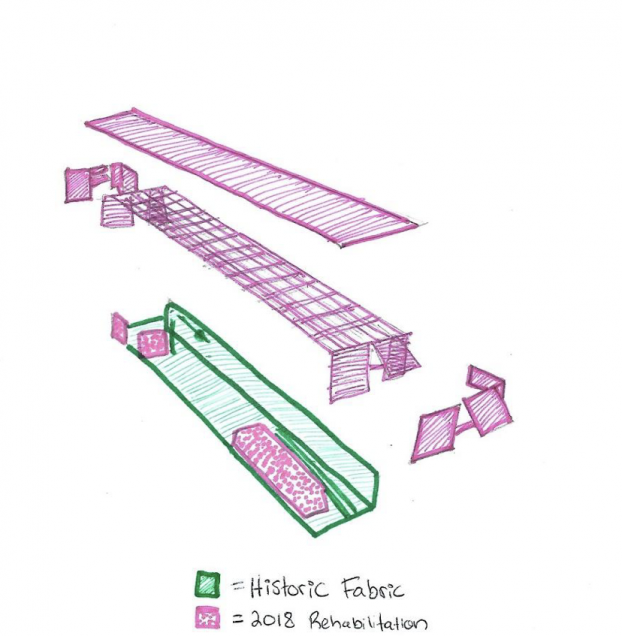

The ICA’s rehabilitation and adaptation of the copper pipe warehouse represents an underutilized option to encourage historic preservation of decaying industrial buildings. The ICA embarked on their adaptive reuse of the condemned warehouse in 2017. The ICA leased the Watershed building from Massport in 2017 and hired the Cambridge firm Anmahian Winton Architects to design the adaptive reuse. The ICA completed rehabilitation of the building in 2018 and opened to the public on July 4th as a summer seasonal exhibition space.[18] The adaptive reuse of the condemned building necessitated significant changes and new structural elements, especially because much of the historic fabric was rotting or filled with asbestos (Figure 1). The building was 15,000 square feet total – the inside space was 50 feet wide and the building had a 25 foot tall ceiling.[19] After the adaptive reuse, the ICA had 9,400 square feet of gallery space and 3,400 square feet for educational projects within the building.[20] (Figure 2) The adaptive reuse project cost about $10 million, which was significantly less expensive than the construction of the ICA’s primary location, which cost $41 million to build in 2006.[21]

The ICA’s goals for the Watershed focused on interpreting the industrial history, functioning and a community asset, and establishing a water taxi service across the harbor. The ICA prioritized the building’s changes to interpret the history of Boston’s industry on the waterfront. According to their press release, “the intent was to preserve much of the essential industrial and historic character while also creating a new architectural expression that makes the building a compelling space for large-scale contemporary art.”[22] The ICA also envisioned the Watershed as a community asset. The ICA created the Watershed as a free exhibition space, so visitors did not have to purchase an admission ticket in either East Boston or the Seaport District to see the exhibitions at the Watershed.[23] The community outreach also extended beyond the art museum’s programmatic mission. According to The Boston Banner, ICA executive director Jill Medvedow “conducted vigorous outreach in East Boston and began building collaborative partnerships with local schools and nonprofits of all kinds.”[24] The ICA staff connected to the community resources in East Boston to develop the Watershed as an asset.[25] The ICA additionally explained that East Boston worked well for their secondary location because they envisioned a water taxi service. The ICA offered the water taxi service from Fort Point to the East Boston Piers Park as part of visitors’ admission when they visited the Seaport location.[26] The ICA’s water taxi service transported visitors across the harbor in either direction in a few minutes. The water taxi service emphasized that visitors could experience both ends of the Boston harbor without driving, but also invited the visitors to explore East Boston through the harborside walk from Piers Park to the Watershed.

Methods of Adaptive Reuse

The ICA rehabilitated the former warehouse by embracing the building’s industrial history, through both the preservation of the historic fabric and by illuminating the “spirit” of the industrial past. The ICA replaced much of the building’s original fabric due to the decay and asbestos. However, they reconstructed a new roof with an industrial appearance (Figure 3). In addition to recreating a non-surviving feature to emphasize the industrial history, the ICA also preserved some of the historic fabric. The museum retained a surviving concrete and cinder block wall, and they emphasized that the “concrete and cinder block wall at one time supported the loading and unloading of rail cars that ran through the building and brought supplies to the facility.”[27] (Figure 4). In addition, the ICA preserved three original metal columns, crane and monorail hoists, and railroad tracks near the front entrance (Figure 5 and 6). The space overall retained the historic fabric in a way that emphasizes the genius loci, or the “spirit of the place” as an industrial facility.[28] To further communicate the significance of the industrial history, the ICA developed a small gallery space that visually interpreted the history of East Boston and the adaptive reuse of the copper pipe warehouse (Figure 7). The “Shipyard Gallery” played a video on repeat that emphasized East Boston’s industrial and immigration history, as well as the Watershed’s adaptive reuse story.[29] The ICA retained the historic character and the story of the building by retaining a large portion of the original fabric and by interpreting the industrial past.

In addition to interpreting the industrial past, the ICA attempted to improve from the original both aesthetically and functionally. The existing conditions inspired some design changes that further rehabilitated the inside of the building. Nick Winton noted that “there were a lot of beautiful things about [the original building] that we noticed right away, one of those was the light that was piercing through that corus roof, giving a beautiful impression of what the light might be like.”[30] The original conditions inspired Winton to develop a 250 foot long skylight, and this skylight highlighted the concrete and cinder block wall (Figure 8). In addition, the architects constructed new doors that illuminated the inside of the building with natural light, and even when closed, the translucent polycarbonate material of the doors allowed natural light in the space (Figure 9). Because the copper pipe warehouse developed in the middle of two neighboring warehouses, the shorter elevations remained one of the few opportunities for natural light. The architect’s choice to prioritize natural light and use that light to illuminate the historic fabric significantly surpassed the original condition of the copper pipe warehouse. The Watershed improved upon the original while highlighting the industrial history.

The architects developed the art museum within the existing large space, which perpetuated the building’s historic program as a warehouse. Except for adding necessary facilities like updated plumbing, restrooms, and locker rooms, the architects made few changes to the large warehouse space. Instead, the large space allowed the ICA to install temporary exhibits that purposefully worked within the open capacity of the building (Figure 10). The architects argued that the project shows “breaking with the customary ‘white room / black box’ gallery paradigm, [and] daylight plays a seminal role in the space, illuminating a major wall and highlighting both ends of the building.”[31] Because the Watershed utilized the large warehouse space, the new program of the building also respected the historical use of the large warehouse. Few historical records prove exactly how the space was used, but the museum could emulate the feeling of the large warehouse by encouraging and prioritizing large art exhibits suited for the warehouse space.

Due to significant deterioration, the architects had no choice but to design something new for the building’s exterior. When tasked with adding onto historic buildings, architects can recreate the original or develop a design that looks completely different.[32] The Watershed’s architects stated that their “design synthesizes the retained infrastructure with equally powerful, new industrial materials” – in other words, using the language of the original to create something new.[33] (Figure 11). The Watershed’s exterior respected the neighboring warehouses because the elevation remained in alignment with the surrounding structures and the new roof also mimicked the black roof line of the neighboring buildings (Figure 12). The translucent polycarbonate doors, which the architects described as the “new industrial” material, blended the structure in with its neighbors. [34] However, the garage doors offered a much wider entrance space, which functioned to welcome large groups of people. (Figure 13). The back elevation utilized the “new industrial” polycarbonate, but the appearance mimicked the surrounding industrial environment more so than the front. The back included a similar garage door and included a terrace space for visitors. However, when the museum was closed, the back door remained closed. From the perspective of the harbor, the building further blended into the surrounding conditions (Figure 14). The back elevation spoke the architectural language of the surrounding industrial environment.[35] Even though the architects updated the exterior, the design overall expressed restraint and respect for the existing conditions of its surrounding environment.

Conclusion

In Hilarie Sheet’s article about the Watershed in 2018, East Boston resident Dan believed that “Maritime life is going away with everything coming into the shipyard.” However, the ICA’s Watershed instead presented an approach that conserved the marina’s character. The building’s history as a warehouse and copper pipe factory for ship production is evident from the retention of the historic fabric, such as the railroad tracks and the monorail hoists. The industrial spirit and feeling of the space remains through the skylight and reconstructed roof. In addition, the museum interpreted East Boston’s maritime history in the Shipyard Gallery. The museum’s program of showcasing large exhibits builds upon the historic program as a large warehouse facility. Overall, the museum’s design suggests that the building respected the existing use as a marina. The exterior design differentiated the additions but used new industrial materials to blend into the harbor’s existing appearance. The Watershed did not encourage maritime life to go away, but instead celebrated and embraced the existing use as a marina.

Dan’s comment that “maritime life is going away” also reflects the narrative of progressive architecture. According to Dan, the East Boston harbor’s character will be lost because it will be replaced with something new. However, the Watershed exemplifies that a building can be updated for a new use and be preserved at the same time. By retaining the heritage associated with the building, the Watershed demonstrates that obsolete environments are not fated to dereliction or replacement. In addition, the adaptive reuse of the Watershed suggested that the industrial history warranted preservation and interpretation. Because the industrial past is not dictated by famous heroes of history and is often associated with grueling labor conditions, it receives less interpretation. However, the ICA decided to illuminate this history through rehabilitating the industrial fabric and by interpreting the stories of the shipyard in an exhibit. Overall, the ICA’s adaptive reuse of the Watershed fought against the grain of architectural decay and showcases how important yet unrecognized chapters of history can be interpreted.

End Notes

[1] Hilarie M. Sheets, “In an East Boston Shipyard, a Watershed Idea for Art,” New York Times, 22 June 2018.

[2] Nancy Seasholes, “Addition of Land” in The Atlas of Boston History, ed. Nancy Seasholes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 72.

[3] George Washington Bromley, Atlas of the city of Boston: East Boston, Mass: Volume Nine (Philadelphia : G.W. Bromley & Co, 1892), 4.

[4] Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Maps of Boston Massachusetts (New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1957).

[5] East Boston Urban Renewal Area R-44, 1965, Folio 63, no 10, Boston Redevelopment Authority, Leventhal Map Center, Boston, Massachusetts.

[6] Michael Kenney details the history of immigrant residents in East Boston, and what remains at Jeffries Poitn today. Michael Kenney, “The Hidden East Boston Offers a Waterfront Without Crowds,” Boston Globe; 24 June 2000: F.1.

[7] For more about Boston’s postwar urban renewal, see Lawrence W. Kennedy, Planning the City upon a Hill: Boston Since 1630 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992).

[8] Bruce Mohl, “Massport serious about waterfront,” Boston Globe, 14 Nov 1985: 81.

[9] Charles Radlin, “Massport, BRA disagree on pier use: East Boston land valued for housing or industry,” Boston Globe, 09 Aug 1986: 17.

[10] Charles Radlin, “Massport, BRA disagree on pier use: East Boston land valued for housing or industry,” Boston Globe, 09 Aug 1986: 17.

[11] William Coughlin, “Massport evicts more boatmen from its piers in East Boston,” Boston Globe, 01 Dec 1988: 27.

[12] City of Boston, “Grand Opening of New Mixed-Income Housing on East Boston Waterfront Celebrated,” July 13 2021. Accessed December 2021. https://www.boston.gov/news/grand-opening-new-mixed-income-housing-east-boston-waterfront-celebrated

[13] East Boston Immigration Station: A Study Report. Boston Landmarks Commission, 2010.

[14] National Park Service, “National Register of Historic Places,” accessed January 2023, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/index.htm

[15] Pamela Jerome, “An Introduction to Authenticity in Preservation.” APT Bulletin 39 (2008 2/3): 3-8.

[16] Marcus Binney, Ken Powell, and Francis Machin, “Decline and Revival” In Bright future: the re-use of industrial buildings (London: SAVE Britain’s Heritage, 1990), 9.

[17] Le Corbusier, Toward a New Architecture (New York: Dover Publications, 1923), 138.

[18] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed.” Accessed December 2021, https://www.icaboston.org/ica-watershed

[19] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed Architectural Fact Sheet,” June 21, 2018.

[20] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed Architectural Fact Sheet,” June 21, 2018.

[21] Robert Campbell, “New ICA building emerges into the light,” Boston Globe, November 30 2006.

[22] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed Architectural Fact Sheet,” June 21, 2018.

[23] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed.” Accessed December 2021, https://www.icaboston.org/ica-watershed

[24] Susan Saccoccia, “ICA expands across the harbor,” The Boston Banner, 28 June 2018: 15, 23.

[25] Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the ICA utilized the Watershed as an emergency food distribution space as well. Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed.” Accessed December 2021, https://www.icaboston.org/ica-watershed

[26] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “Watershed Shuttle Schedule.” Accessed in October 2021.

https://www.icaboston.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/watershed_shuttle_schedule%5B1%5D.pdf

[27] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed Architectural Fact Sheet.” June 21, 2018.

[28] Bie Plevoets and Koenraad Van Cleempoel, “Chapter 2: Intervention” in Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage: Concepts and Cases of an Emerging Discipline (London: Routledge, 2019), 31.

[29] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed: From Condemned to Contemporary Art Space,” June 27, 2018. Accessed via Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Yn5XN31IcM&list=PLgK0CYNpzjV1eRY8HFjLG8hbT8FwHG1Jm&index=5

[30] Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, “The ICA Watershed: From Condemned to Contemporary Art Space,” June 27, 2018. Accessed via Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Yn5XN31IcM&list=PLgK0CYNpzjV1eRY8HFjLG8hbT8FwHG1Jm&index=5

[31] Anmahian Winton Architects, “ICA/Boston Watershed.” Accessed October 2021. https://www.aw-arch.com/ica-watershed

[32] Steven W. Semes, “‘Differentiated’ and ‘Compatible’: Four Strategies for Additions to Historic Settings,” Forum Journal Vol. 21 No. 4 (Summer 2007), 19.

[33] Anmahian Winton Architects, “ICA/Boston Watershed.” Accessed October 2021. https://www.aw-arch.com/ica-watershed

[34] The alterations align with Stephen Semes’ definition of “abstract reference.” Abstract reference attempts to differentiate the addition from the original, but “makes reference to the historic setting while consciously avoiding literal resemblance or working in a historic style. Steven W. Semes, “‘Differentiated’ and ‘Compatible’: Four Strategies for Additions to Historic Settings,” Forum Journal Vol. 21 No. 4 (Summer 2007), 19.

[35] The back of the museum mimicked the surrounding environment, so it aligned closer with Semes’ definition of “Invention within a Style.” Semes argues that “this strategy, while not replicating the original design, adds new elements in either the same or a closely related style, sustaining a sense of continuity in architectural language.” Semes, “‘Differentiated’ and ‘Compatible,’” 18.