Saccharomyces Serenades, Lactobacillus Lullabies: The Soundscapes of Fermentation

By Dana Ferrante

It’s not everyday you meet a self-proclaimed ‘fermentation evangelist,’ let alone play a small part in his upcoming exhibition.

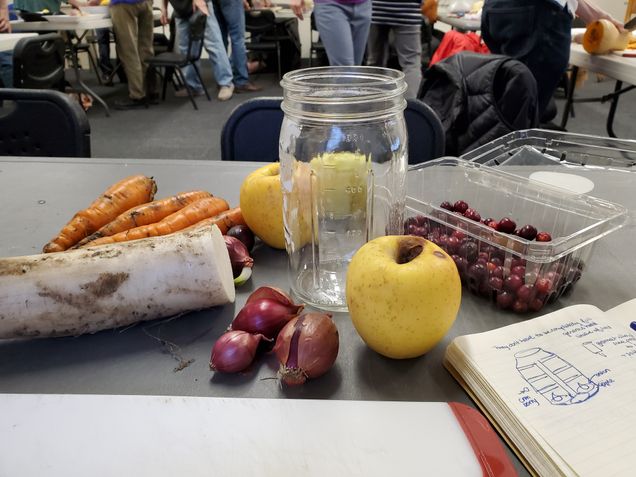

On February 1, 2020, I participated in a workshop for the members and friends of the Somerville Community Growing Center led by Joshua Rosenstock, an artist, musician, fermentation expert, and Associate Director of WPI’s Interactive Media & Game Development program.

The workshop had an eclectic mix of participants, including community garden and farm members, pickling enthusiasts, musicians, young children and their intrigued guardians. The task at hand was relatively simple: using produce from Waltham Fields Community Farm, we were to create pickle jars that would then be connected to Joshua’s living art piece, The Fermentophone.

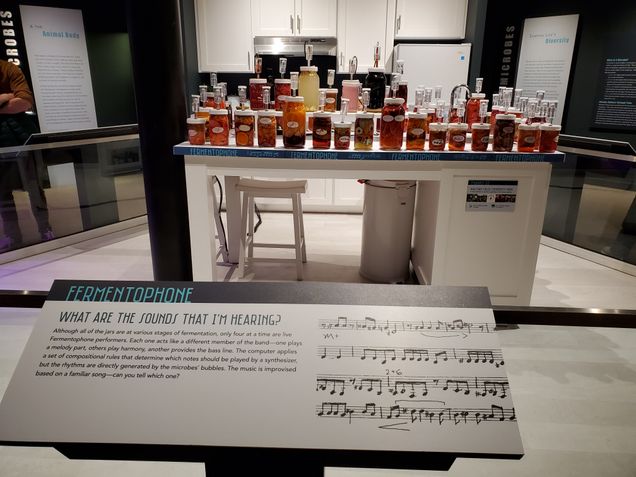

According to Joshua’s website, the “Fermentophone is a multi-sensory installation in which an algorithmically generated musical composition is performed by living cultures of bacteria and yeast. The installation comprises a series of different vessels containing actively fermenting foodstuffs and beverages, wired with electronic sensors. Each colorful, odorous, and edible ferment has its own musical vocabulary which is expressed according to microbial activity. ”

Joshua created his first Fermentophone installation back in 2013 at a festival at MIT’s Media lab; since then, he’s exhibited his idea in an empty storefront in Wisconsin as part of the state’s Fermentation Fest, as well as a similar festival in Boston in 2016. The fruits of our labor in February 2020 were destined for a temporary installation within the Harvard Museum of Natural History’s exhibit, Microbial Life: A Universe at the Edge of Sight, a “multimedia journey into [the] fascinating, invisible realm” of bacteria and microbes (HMNH website, 2020).

Before we began carefully stuffing our mason jars, Joshua gave us some very important background information on the history, power, and process of fermentation. Here are the key takeaways:

1) Microbes, or the yeasts and bacteria responsible for the fermentation process, are everywhere.

Evolutionarily speaking, microbes preceded humans, and likely exerted selective pressure on humans—which is both a humbling and somewhat terrifying concept. Humans are majority microbes, and we exist in a symbiotic relationship with them (you may have heard the term ‘microbiome’). Little is known about the gut-brain axis in the human body, which is organized around microbial activity, but scientists have established it plays a role in regulating some of our thoughts and emotions. (Hence, somewhat terrifying.)

2) Saccharomyces, a genus of fungi, includes many types of yeasts humans have used to create food and drink for at least 12,000 years.

From beer in the Epic of Gilgamesh, to ancient Chicha pots unearthed in the Andes, to depictions of the Greek god Dionysus with satyrs and wine glasses, strains of Saccharomyces have been harnessed throughout human history, around the world, to produce fermented, alcoholic beverages. Many have attributed the existence of bread, beer, and other fermented food and drinks to a rise in surplus grains due to the agricultural revolution (approximately 10,000 BCE).

As Joshua pointed out, microbes not only control different physiological processes (e.g. gut-brain axis, microbiome, etc), but have the power to expand our minds. Accordingly, fermented beverages in a variety of cultural contexts have gained significance beyond pure nutrition; for example, beer was once used as a form of currency or salary, and chicha, bread, and wine are linked with spirituality in cultures across the globe. Today, yeast continues to produce delicious breads and brews, as well as some kinds of synthetic insulin and some vaccines.

3) Another microbe, lactobacillus, can survive where many microbes can’t; this often leads to spontaneous lacto-fermentation.

When vegetables are put into a salt water brine, the salt drives out the water in the vegetables. Very few bacteria can survive in this context, with the exception of lactobacillus, which imparts that distinctly sour, tangy flavor we associate with a good yogurt or lacto-fermented pickle. Lacto-fermented foods are found in cultures around the world, from kimchi to sauerkraut, Greek yogurt to miso.

Joshua was quick to point out that for much of human history, fermentation was one of the only ways humans could preserve foods. Until the advent of refrigeration beginning in the 1930s, harnessing microbes was one of the best and most common ways to save food for later.

4) Not all pickles are fermented.

As someone who enjoys pickling any and all vegetables, this was something I knew in the back of my mind, but didn’t really want to admit, I guess. Like many impatient, city-dwelling folks living in a shared space, I am always a bit weary about letting things I plan to eat actually ferment. I love vinegar, and am pretty skeptical about the type of microbes that might be living in my apartment….

So what foods are actually fermented? Pickles that undergo spontaneous lacto-fermentation are ‘real’ pickles, according to Joshua. When vegetables are “pickled” in vinegar, their immersion in a highly acidic solution (e.g. vinegar) essentially ensures their preservation. In contrast with a salt water brine that encourages spontaneous chemical reactions, vinegar inhibits any spontaneous microbial activity. In order for the Fermentophone to work, our pickle jars needed to lacto-ferment, thereby releasing bubbles and producing the Fermentophone’s rhythm.

Ultimately, this hands-on experience has made me significantly less afraid to lacto-ferment pickles, and I cannot wait to use New England’s bounty of late summer vegetables and give it a try.

Aside from the fact that Joshua’s installation involved the community in a very hands-on way (Harvard’s Food Literacy Project and students from a local school also contributed mason jars), I think what makes the Fermentophone so clever is that it uses live organisms to create “generative art,” as Joshua called it.

The Fermentophone translates the chemical process of fermentation into a sonoric experience, while also connecting science with visual art, the culinary arts, and questions of cultural significance. While we could curate the colors, shapes, layering, titles, and flavors of each mason jar, the Fermentophone produced “serendipitous” sounds and experiences.

As a student of gastronomy, this experience has made me reconsider the mediums and sensory experiences one can harness to explore topics in food. While I have often found myself wondering what the food in an 18th century kitchen tasted like, I now found myself thinking: what would that kitchen have sounded or felt like? What can I do as a gastronomy student to make better use of sonoric, tactile, and visual mediums in my research or presentations?

Lastly, a quick apology: the Fermentophone exhibit, to the best of my knowledge, has been dismantled at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. That said, a visit to the museum is certainly worth the while for gastronomy students, especially with the Peabody Museum’s Resetting the Table: Food and Our Changing Tastes exhibit happening right next door until November 28, 2021.