Korie Tinch

A PhD student in Boston University’s American & New England Studies program, Korie Tinch draws upon queer theory and the social sciences broadly to investigate the construction and maintenance of sexual identities through popular culture. Korie approaches this topic through the lens of contemporary media consumption, especially underground music movements, reality television, and digital media. Korie’s most recent line of research focuses on the roles of gender and sexuality among “Juggalos,” the vibrant subculture rooted in a dedicated fandom surrounding hip hop group Insane Clown Posse.

Skate Dudes and Str8 Dudes:

Normative Sexuality and the Jackass Media Franchise

Introduction

In a 2010 Vanity Fair interview promoting Jackass 3D, franchise star Steve-O commented that the team behind the television and media franchise “always thought it was funny to force a heterosexual MTV generation to deal with all of our thongs and homoerotic humour;” he further claimed that said humor “has been a humanitarian attack against homophobia” and that in his opinion, “gay people really dig it too.”[1] The case Steve-O makes for Jackass having a thoughtfully anti-homophobic mission—especially one that is received as such—is intriguing but tenuous when measured against public response to the franchise. Jackass has long been derided as pointless and crude, with one particularly scathing, “zero star” review of the first film published by the New York Post lamenting the “depressing” fact that “the mostly male audience at a screening…laughed heartily at what was half a step up from a snuff film.”[2]

Recent years have seen more favorable reception of the franchise. 2022’s Jackass Forever notably holding a critical score on Rotten Tomatoes of 86 percent compared to the first film’s 49 percent.[3] A standout review of Forever by BuzzFeed culture writer Shannon Keating credits not just the film but the franchise overall with a palpable sense of earnest sweetness below its low-brow, slapstick surface. She writes that, as a viewer, “you come to watch somebody get hurt in the most absurd possible way, but you stay because these guys love each other endlessly for it.”[4] Keating also attends to the homoerotic optics of the film and franchise in the course of her revie—just one example amidst the Jackass renaissance of popular journalists now articulating the franchise’s materials with queer experience, or locating where that articulation is being voiced through public discourse on social media. In a 2021 piece that calls back to the 2010 Vanity Fair interview, Joseph Earp proclaims that Steve-O and the other cast members’ words therein only served to make more widely known that which had always been obvious “for astute fans.”[5] Yet main cast members prior to the franchise’s fourth and most recent film have been white, male, cisgender, and not openly queer themselves—and the lion’s share of consumers of their work have always been presumed to fit the same description—even as much of their content relies upon male nudity and psycho-sexually charged antics.

To what extent can the appeal of these flirtations with homoeroticism in fact be reduced to “benign violation”[6] for an overwhelmingly heterosexual audience? Is it possibly the case that a deeply self-aware, critical engagement with the norms of gender and sexuality is at the heart of Jackass, and that message is reaching a receptive queer audience? Or is the cast’s suggestion of that being the case a matter of exaggeration? I seek to resolve these questions through the analysis of source material and its aggregate reception by the public. I approach this analysis through frameworks of key writings on gender and sexuality, with masculinity in the contemporary United States as a particular focus. I do not wish to ignore how the interpretation of Jackass by its straight male viewers was at one time inextricably linked to negative public perceptions of homosexuality and gender nonconforming behavior and include closing statements that problematize that cultural linkage. Still, my article highlights a self-evident thread of queer audience identification with the Jackass brand within popular media discourse. I advocate for such discussions to be taken as serious entries to the archive of queer media criticism. The question of whether the makers of the franchise authentically “intended” for its content to resist a heteronormative order is difficult to resolve; in any case I maintain that assessing it through the lens of queer frameworks to explore what it does for the queer viewers who claim it—as shown subsequently—fits productively into the study of gender, sexuality, and culture. Ultimately, I present this case with the aspiration of furthering the project of destabilizing the rigidity of the heterosexual and queer as cultural categories.

Literature Review

The work of Jane Ward serves as a natural keystone for exploring the relationship between Jackass and contemporary masculinities. My title references a 2008 article by Ward on “dude-sex” as well as her 2015 book, “Not Gay: Sex Between Straight, White Men.” Based upon extensive analysis of m4m (male-for-male) craigslist personal ads, Ward’s texts present a subset of self-identified “str8” men who seek out same-sex encounters while maintaining their heterosexual identity, for whom “straightness is constituted by their way of life” instead of their sexual activities; rather, “it is performed and substantiated through a hyper-masculine and misogynistic rejection of queer culture.”[7]

Not Gay expansively applies Ward’s nuanced conception of straight identity as a social category that doesn’t bear a linear relationship to actual sexual experience—particularly for otherwise heteronormative white men—arguing that “homosexual sex plays a remarkably central role in the institutions and rituals that produce heterosexual subjectivity, as well as in the broader culture’s imagination of what it means for ‘boys to be boys’”; the book significantly claims that not only do homosexual encounters not necessarily compromise men’s heterosexual social status maintained within a the landscape that casts “straightness and queerness primarily as cultural domains” but in fact plays a hand in constructing and reifying said identity.[8] I take up this central argument, utilizing it in my attempt to disentangle the notion that the homoerotically charged scenes throughout the Jackass franchise may indeed just be a matter of shock and grotesque amusement for an otherwise unbothered, heteronormative male audience. Ward briefly engages with Jackass in the fourth chapter of Not Gay as one example among popular media that compels “viewers to celebrate homosexual play among edgy white dudes who are so reckless that their homosexual behavior reads as a macho display of endurance and self-sacrifice—a homosexual sacrifice made for the sake of our entertainment” and to a lesser degree, as a possible self-reflective engagement with masculinity that “models a way for young white men to disidentify with the knee-jerk homophobia of their generation,”[9] but she does not linger upon the details of its contents nor its contentious impact upon queer viewers, which I subsequently elaborate on as the main focus of my own argument.

I also follow Ward’s own reference to Jack Halberstam’s The Queer Art of Failure. Ward has characterized Jackass after Halberstam as an example of “precisely the genre of lowbrow white male ‘stupidity films’…that has the potential to disarm white hetero-masculinity by allowing it to be incompetent, ignorant, and forgetful of its own status and function.”[10] While Ward mostly references Halberstam’s formulations of ignorance and stupidity as potentially subversive ways of life, I extend the connections to his text. Jackass has effectively been characterized by its detractors as a failure of taste and decency. I argue that this sense of “artistic failure” marks opportunity for the Jackass crew to practice a sense of sincerity that many more “serious” artists may struggle to access, motivated by the goal of critical success. In Halberstam’s own words—deployed by him to critically assess the academy—”being taken seriously means missing out on the chance to be frivolous, promiscuous, and irrelevant.”[11] Parallels might be drawn between Jackass and any number of iconic queer bodies of work that have been targets of or responses to respectability discourse as it pertains to art; Jackass especially shares proximity to camp filmmaker John Waters who has long championed the franchise, befriending and collaborating star Johnny Knoxville, even appearing briefly in the series’ second film installment. In subsequent sections I elaborate on how this interpretation of the franchise as an example of subversive, artistic failure cuts across various themes in The Queer Art of Failure, from the underestimation of so-called “lowbrow” media and cultural projects to the role of unbecoming in gender performance.

Additionally, themes of earnest platonic affection between cast members characterized as non-stereotypical displays amongst straight men arise throughout the public discourse surrounding Jackass. I have related these themes not only to Ward’s reflections on the often underestimated and denied ambiguity of even heteronormative homosocial relations, but also back to models of queer social organization posited by Michel Foucault.

The materials to which I apply above frameworks range from the content of Jackass itself, to public response in the form of commentary on social media and popular press. Tweets by queer individuals who identify Jackass as formative to interpreting their own identities make up most of the former, while the latter includes several online articles and, significantly, an episode of the StraightioLab podcast that focuses on Jackass. In the following section, I describe some of the events and general aesthetics of the franchise, using key moments from the 2006 film Jackass Number Two as case examples. Later, I juxtapose the 2000’s era antics of the cast and crew with some very visible difference in the content their most recent film (2022’s Jackass Forever), but as my analysis takes up the reflections of viewers who identify their earlier works as formative media, those entries into the franchise constitute my natural starting point and primary focus.

Examining the Content of Jackass

Deliberate appeals to shock and disgust have always been essential to the franchise’s formula and what audiences expect to see from it. There is a consistent emphasis on nudity and raunchy humor in the content. In many instances, it is genital proximity between male cast members, as well as the infliction of pain to genitals, from which Jackass extracts its humor.

A mere four minutes into the run time of Number Two and directly following the film’s suburban running of the bulls introduction sequence, the viewer observes a scene in which a “puppet” that is shortly revealed to be cast member Chris Pontius’ flaccid penis—comically disguised as a mouse with fabric and googly eyes—is attacked by a captive snake. Fellow cast member Johnny Knoxville is manipulating Pontius’ genitals as if a marionette and narrating the scene in character as a magician while the rest of the cast look on gleefully and laugh (0:04:31).

A few segments later, Jackass cast member “Danger” Ehren McGhehey and motocross athlete Thor Drake (making a guest appearance) are shown attempting to complete a vertical loop on miniature motorcycles. An unseen cast member (possibly Chris Pontius) comments from off-screen, “I love that confidence. I’m not gay but I… I kind of want to fuck him” regarding Drake as he’s seen approaching the loop (0:13:06). At the conclusion of the stunt, Pontius jokes that McGhehey is “totally going to lose [his] virginity” after the movie’s release, to which McGhehey laughingly responds, “I don’t think dudes count, Chris” (0:13:45-0:13:52).

Immediately following the loop sequence is a scene in which Bam Margera’s buttock flesh is branded with a hot iron. The crew is onsite at a cattle ranch, and both Ryan Dunn—Margera’s castmate and close friend who ultimately administers the brand—and Johnny Knoxville provide complimentary description of Margera’s bare rear. Knoxville then attempts to help stabilize Margera as Dunn heats up a metal instrument crudely resembling a penis and testicles which he proceeds to brand Margera with as several cows look on calmly (0:14:08).

Numerous other moments from the film may be considered tenuously charged with homoerotic or queer implications, including Margera’s request to have a dildo launched at high speed (via carnival strength game apparatus) towards his anus rather than a heavy weight launched at his testicles (0:10:35-0:11:08), or his off-handed comment that he would “French kiss” Knoxville for hypothetically accomplishing a particularly risky stunt involving rubber balls propelled by a powerful explosive (0:33:31-0:33:39); Chris Pontius—whose appearance in revealing women’s clothing is a frequent component of Jackass productions—standing by in a flowered bikini and bunny ears as Wee Man and Preston Lacy tandem bungee jump off of a Miami bridge (0:25:15-0:25-19); John Waters’ aforementioned brief appearance as he presents a “disappearing act” in the form of Wee Man, in his underwear, being body slammed into a mattress by a much larger and equally undressed woman (0:37:09-0:37:40). These clips from Number Two are fairly representative of the content featured throughout the show and film series. Said typical content makes up many of the examples that might be cited by viewers as variously either degrading or affirming to individuals whose identities or experiences are sexually marginalized. Though the filmmakers’ intent obviously cannot be measured by an observer, the remainder of this article interprets responses to this material mostly through the lens of queer viewership and compares the perceptions thereof with relevant theoretical literature, largely on the homosexual activities of white men who are understood to be heterosexual social and cultural subjects.

Queer Reception and Analysis

While there are several instances of critics and fans avowing the franchise’s queer leanings that I will explore in this section, the one that best encapsulates recurrent and significant themes may be the Jackass centered episode of the StraightioLab podcast. The show’s tongue-in-cheek description declares it to be “an intellectual podcast where smart comedians George Civeris and Sam Taggart unpack the rich, multi-colored tapestry of straight culture,” while the episode in question is described in a manner that sets up the hosts’ subsequent humorous yet genuinely thought-provoking meta-analysis of their topic:

Intellectual powerhouse Sarah Squirm joins Sam and George to unpack the cultural legacy of the subversive feminist art project known as the Jackass franchise. Gender politics, self-harm, trigger warnings, the failures of television criticism, the field of linguistics… it is ALL addressed. This episode is the podcast equivalent of jumping off a bridge into alligator-infested waters while your boys look on. For your own safety, do NOT try this at home.[12]

The hosts and guest Sarah “Squirm” Sherman identify how a generous reading of the franchise can locate within it models of care, self-awareness, exploration of bodies and identities. They also stress its subversive elements of social nonconformity and a sense of artistic integrity that is unconcerned with critical recognition. Simultaneously, they identify a disconnect between their contemporary identification with the material as gay and female spectators versus the reception of the show and early films in the franchise at the time of their release.

Civeris, Taggart, and Sherman’s thoughts are strikingly echoed throughout other responses from a variety of writers and average social media users alike. My own cursory review of Tweets around the time of Jackass Forever’s release in early 2022 turned up over fifty examples of users describing the franchise’s relationship to the development of their own gender or sexual identity. In the next section I will explore in-depth the ostensibly queer dimensions of Jackass and its fandom, as well as consider counterarguments based on its role outside LGBTQ lives and communities. I do so by analyzing pull quotes from the podcast, articles elaborating on the above themes, and example Tweet screenshots I have collected through searches that mention both Jackass and key terms related to queer identity.

Care, Community, and Kinship

“Jackass is pro-gay but someone using those exact tactics to, like, bully you in school is not…because everyone in that show is part of a community, they have agreed to the rules, and they are, in fact, using a form of group therapy to process their trauma. They have their version of safe words…it is within a safe space.”

-George Civeris[13]

Some of the features most consistently noted by the hosts of StraightioLab and other queer commenters are negotiation, agreement, and encouragement throughout the participation of the Jackass crew in their own antics, and how the nature of their association with each other is exactly what enables them to pursue such physically and creatively ambitious feats in their work. While Civeris’ suggestion that they are using this environment to “process their trauma” is decidedly tongue-in-cheek, he and his co-hosts are hardly the only people to have commented on the possibility that Jackass showcases or implies a certain amount of unpacking the expectation that men be emotionally closed off to those around them. Other commenters have quite seriously considered that the cast’s collaborations have facilitated exploring alternative, care-driven masculinities. Journalist Jess Thomson’s 2022 piece on the franchise’s so-called “positive masculinity” and its reception by queer viewers champions it as exceptional amongst its 2000’s era comedy contemporaries for showing men “comfortable with each other’s bodies” to the degree of homoeroticism, but “in a way that doesn’t mock being gay;” she suggests that it was refreshing for audiences to witness in media “dudes just genuinely caring about each other…they always help each other up off the ground, regardless of who knocked them over in the first place.”[14]

“They’re all hot, they’re all hilarious, they’re guys hanging out with their friends—they’re all REAL FRIENDS. We all see these [other] shows—like, these reality shows where you see a group of friends all doing stuff? They’re not friends. They don’t like each other.”

-Sarah Sherman on the cast of Jackass[15]

Such a reading of Jackass not only points out the sense of sincere affection and closeness exhibited by the cast members but also represents them as notably rare displays in their historical context. The hosts of StraightioLab especially contrast this to other works in the reality television genre—such as the Real Housewives franchise—that rely upon interpersonal conflict and apparent histrionics for entertainment. At the same time the dynamics at work in Jackass are problematized by Civeris as something that until just last year excluded any women, and arguably is part of a cultural metanarrative that glorifies male homosocial relations for being perceived of as free from pettiness or drama that ostensibly undermines the depth of female friendships.[16] But the podcast’s earnest engagement with the centrality of trust and communication to the Jackass’ creative process relates it back to what Sherman describes as an intentional “consenting community that has the common understanding of play and laughter” among the cast.[17]

Again, this apparent model of care baked into the foundation of Jackass is a frequent focus of commentary in a multitude of the sources I have examined. Thomson’s piece includes interview quotes from two other queer Jackass fans affirming this interpretation. These respondents emphasize how the cast has projected a sense of being “very supportive and brotherly with each other,” expressing their masculinity in a way that is “taken so lightly and positively, it feels safe to engage in,” especially when framed in contrast to male-centric comedy that directly targets minorities (sexual an otherwise) as the butt of its jokes—something Thomson and her respondents likewise remarked the series surprisingly avoided leaning upon during its early success.[18]

Shannon Keating and Joseph Earp’s articles also cite moments of vulnerability that accompany the crassness and danger as examples that counter the series’ reputation as a bastion of toxic masculinity. Following Ward, it might be argued that the heteronormatively “necessary” performance of masculine strength and unseriousness across the rest of the content “justifies” these glimpses of tenderness and precludes them from becoming threats to the straight identities of their various actors. At the same time, the idea that the cast exhibits some expansively queer “way of being” in their interactions is hardly unprecedented. In the highly influential Friendship as a Way of Life, Michel Foucault elaborates upon subjects becoming or embodying queerness by relating to each other socially in ways that are as much or more “unsettling” to the scripts of heteronormativity than even homosexual contact. He characterizes his own lifelong experience of “being gay” as at its core about “want[ing] relations with guys…not necessarily in the form of a couple but as a matter of existence,” such as the sharing physical space (nonsexually) and emotional vulnerability.[19]

Yet what of the presence of those acts we might define as homosexual according to Ward’s usage “as a technical description of same-sex sexual behavior”?[20] As I have established, both genital proximity and sensory excess, usually in the form of pain, are integral to Jackass. Ward’s theories, even with a concession to the self-awareness of the franchise, would likely explain the acts of pseudo-sexual intimacy—the nudity, proximity to and targeted abuse of the genitals—primarily as iterations of the bonding rituals of endurance through combinations of the (sexually) humiliating and physically daunting long associated with esoteric, white male social spaces that rationalize such displays as vacated of sexual meaning. As such, in a sense the cast may be viewed as “inoculated…against authentic gayness”[21] particularly in the eyes of straight viewers whose cognitive dissonance wards off reflection upon their own sexual subjectivity. But by the same token it is this very denial that suggests there is a lurking homosexual threat, the avoidance of which must be cultivated by the viewer to maintain their own heteronormative status. While cast members don’t outwardly express sexual gratification from these activities, they are a source of some delight and perhaps an extension of Foucault termed making oneself “infinitely more susceptible to pleasures.”[22] The hosts of StraightioLab and others have likened some of the stunts to “exploration of kink.”[23] Underscoring such an assertion is the notion that many of the cast’s activities on display (genital torture, gender nonconforming dress, nudity, and so on) are analogous with deliberate deviance from sexual norms for sexual pleasure. At the very least, these encounters constitute exploring the uses of the body for sensory excess in often socially unsanctioned ways. The following section delves into the role of and reflections upon the body—white, cisgender, and male or otherwise—woven into the franchise.

Embodiment, Dis/identifying, Un/Becoming.

“The fact that they’re hot, as you said, is like part of that too.. You’re saying, ‘look, these guys are like, white men…that have the body that we are conditioned to think is ideal. Now we’re gonna literally have an alligator bite their nipples off.’”

-George Civeris[24]

Halberstam refers to masochism on the part of men as a behavior that “inhabits a kind of heroic antiheroism by refusing social privilege,” while “the female masochist’s performance is far more complex and offers a critique of the very ground of the human.”[25] Arguably the self-injurious antics showcased on Jackass may speak to both characterizations of masochism. Civeris describes some degree of alienation experienced as a viewer on the outside of heterosexual normalcy, felt as an “envy of being liberated enough to destroy your own body,” while he also characterize the franchise’s frequent deployment of “danger specifically targeting the male genitalia” as aesthetically compatible with a certain radical feminist perspective.[26] This interpretation casts the stars’ work as a form of self-critical, or even self-deprecating, engagement with masculinity through the violation and destruction of (largely, traditionally attractive) male bodies.

“What do you do to escape the violent architecture of masculinity?

You literally self-combust by destroying your masculine body.”

-George Civeris[27]

I argue that what queer viewers seem to widely take away from these feats of bodily strain is a philosophical interrogation of what the body is “supposed to” be or do. Much of the negative response Jackass has received relies upon an implicit disgust at the “abuses” the cast put themselves through, with their work routinely being characterized as stupid, incapable of providing insight or benefit beyond juvenile entertainment. If we take seriously the possibility that the cast are deconstructing an imagined strict narrative of what the body is “supposed” to be put to productive use—socially and economically speaking—then their antics illustrate another register of critical embodiment. Might this not be its own response to the expectations of liberalism “where certain formulations of self (as active, voluntaristic, choosing, propulsive) dominate the political sphere,” compelling actors to do something “worthwhile?”[28] Halberstam discusses this liberal selfhood in opposition to what he calls “radical passivity” on the part of female actors, but the same liberal values might be criticized through the avenues of time-wasting, as well as compromising the body’s integrity and subsequently its ability to operate “productively.” This line of analysis has implications critical of capitalism and the Protestant work ethic, as well as calling into question bioessentialist arguments against medical transition, the latter of which has been especially implicated in the comments trans and gender nonconforming viewers.

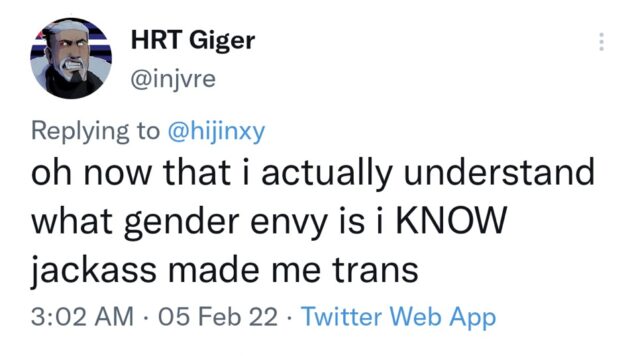

Around the release time of 2022’s Jackass Forever, film critic Henry Giardina compiled tweets in which transgender fans of the franchise explicitly linked their affection for the series to trans identity and experience. Giardina’s examples echo the StraightioLab hosts’ identification of kink as an element of the Jackass brand, idly musing its role in the realization of “gay little trans mascs into bdsm,” while others seem to stake more explicit claims about the series’ formative role—that it “made them into the dudes they are today.”[29] Many tweets I encountered in repeated searches expressed similar or related sentiments.

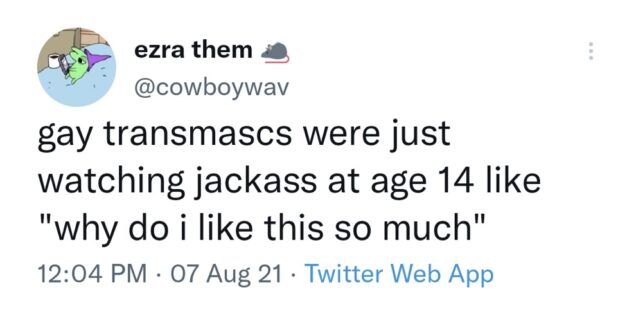

User @cowboywav’s above tweet (figure 1) is hardly the only one I could personally locate that articulates early exposure to Jackass especially with transmasculinity. I collected screenshots of at least twenty-two example original tweets—some of them threads with subsequent responses—most of which referenced the concept of “gender envy” inspired by the members of Jackass. The PFLAG National Glossary defines gender envy as “a casual term primarily used by transgender people to describe an individual they aspire to be like. It often refers to having envy for an individual’s expression of gender” and “is sometimes experienced by people expressing themselves outside society’s gender stereotypes.”[30] A tweet at the time of Forever’s release by user @injvre not only cites this phenomenon as one the author has experienced, but goes on to claim that the franchise “made them trans” in some regard (figure 2).

Culture writer Niko Stratis published an article titled “Jackass Made Me the Trans Woman I Am” through now-defunct Bitch Media on the date of Forever’s release elaborating trans identification with the franchise in great detail. She describes being “by all outward appearances…a young man among other young men” who nonetheless “never quite felt like a man” and “struggled” with the expectations placed upon her to “become” one; Jackass presented for Stratis what she perceived to be an alternative masculinity, one exhibited by the same “types” of men that populated here surrounding but who exhibited “little of the bullying bravado I’d witnessed at my local skate park.”[31] Crucially, although the franchise relies on the body as a site for humor, Stratis characterizes the uses of the body at work therein not as a reinforcement of a masculine physical ideal but a break from it. As Stratis

tried to find my place in the skate park, it seemed that my masculinity was measured in the prospective inches of my genitalia. And as I grew to understand my body as one I felt disconnected from, I developed anxiety around not being classically manly enough. I just wanted to learn to kickflip down some stairs; balls didn’t seem to be necessary to do that. Jackass, by contrast, seemed to make an enemy of balls: Along with dicks, they were under constant threat of attack.[32]

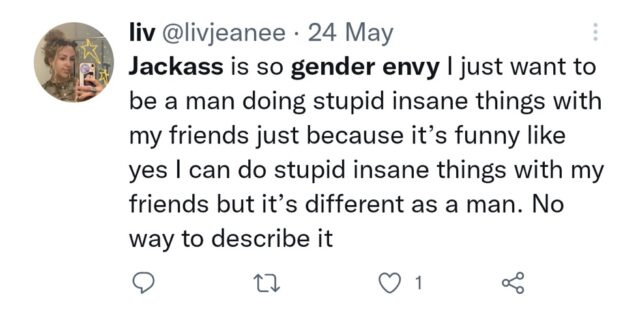

She goes on the claim that the crew exhibited “a notable lack of language around dicks being the core of a man’s strength,” which, however tenuously—and I will consider the opposite argument in this article’s closing section—threatens to upset contemporary narratives equating anatomy with gender determinism. It remains unclear whether the “gender envy” described by the aforementioned Twitter users is contrarily a matter of desiring to inhabit the perception of masculine bodies onscreen. However, some cited the likes of watching the cast “doing stupid insane things” together as the target of this feeling (figure 3), suggesting that for them a sense that what they were missing out on was the ability to behave like men or boys—supporting Stratis’ reading of Jackass as championing a masculinity not grounded in the physical, and reinforcing earlier points about the centrality of friendship in the crew’s dynamics as something longed for by non-cishetero male viewers.

Art, Rebellion, and Respectability

“The commitment is a real like, thing…So many people are like, half-assing everything they do, especially in the entertainment industry. Sort of being like, ‘well how can I just like, clock in, baby, and get like, my royalties. And be like, the most inoffensive that I possibly can be for a half hour on NBC.”

-Sam Taggart[33]

I have referred briefly to what I perceive as Jackass’ proximity to queer media that gladly embraces the sensational and the grotesque. This to me is an essential consideration for explaining the appeal the franchise has to queer viewers that by now I hope is well-established. It is the sense of unwavering gumption in the act of performing—what Sherman calls “commitment to the bit-ment”—which Civeris uses to credit, however humorously, his claim that “Jackass is more politically progressive than the LGBTQ center” he was the head of on a college campus.[34] Recent years have seen the expansion of “family friendly” content featuring queer characters or displays, accompanied by debates about homonormativity and the expectation of performing socio-moral purity in order to assimilate into mainstream culture, as well as misgivings about the sanitization of art and media broadly. Against this backdrop, the puerile and vulgar contents of Jackass may be read as critical provocation.

To begin addressing Jackass’ contentious subversiveness, I think it is pertinent to not discount that the cast’s stunts—including and perhaps especially genitally targeted ones—may be tantamount to seeking thrills and danger as a display of masculine eminence, however differently they may be interpreted by individual viewers. Likewise, their homoerotic displays may well amount to little more than a flavor of “defiant stunt[s] that produced among onlookers the desired degree of shock,” the likes of which Ward characterizes the Hell’s Angels kissing as much as “an expression of ‘lust’ and ‘brotherhood.’”[35] I close my analysis by delving more extensively into less optimistic readings Jackass, including its overlap with queer experience.

Problematizing Intent, Interpretation, and Legacy

“The legacy of [Jackass]…whether it’s their intention or their fault or not, it did inspire some of the worst behavior among teenage boys—and later, adult men.”

-George Civeris[36]

As much as can be said about Jackass’ appeal to queer viewers and its illuminating visions of gender performance in action, there remains the question of how intentional these outcomes have been throughout the creative process. There also remains the problem of how the more negative iterations of its influence were felt by young queers through the conduit of straight teenage boys and young men looking to emulate the cast’s antics. The StraightioLab episode addresses these issues more directly than the articles I have cited. Taggart in fact suggests that there has been an ongoing and emphatic “artpop-ification” of the franchise that perhaps only retroactively casts its content as “pro-gay” and “commenting on masculinity instead of embracing it.”[37] Both he and Civeris cite episodes of explicitly homophobic bullying at their expense by fellow high school students who idolized the Jackass cast. While Steve-O and his collaborators may purport that inclusivity and support of queer viewers is at the heart of their work, that aspiration became dislodged in the ways that many young, straight male viewers regurgitated what they took to be the point of the series.

Civeris, Taggart, and Sherman’s comments also allude to the advent of outright damaging prank-based digital content that boomed within the last two decades. Others have explicitly deemed the rise of said content—the existence of which as a cohesive and far-reaching phenomenon came after the 2005 launch of YouTube, nearly five years after the premiere of Jackass on MTV—arguably a direct effect of the success of the series. Writing for NBC at the time of Forever’s release, Morgan Sung went so far as to claim the “franchise laid the foundation for the prank culture that long dominated YouTube and Vine.”[38] Sung cites Sam Pepper as a notable example, having been the subject of multiple controversies involving sexual misconduct in association with a specific prank video in 2014, and in 2016, a video created under the pretense of faking the murder of one of Pepper’s friends in front of another; the prank target’s ignorance was later revealed to be fabricated. Despite these incidents, Pepper maintains a significant online following.[39] More recently, YouTube star David Dobrik, whose wildly successful content has relied on “daredevil” behavior, has been the subject of similar claims about perpetuating and facilitating sexual misconduct, and additionally engaged in a stunt that resulted in his former friend and collaborator Jeff Wittek’s grave injury and near death.[40] With the exception of Bam Margera, most of the Jackass cast by contrast have not been the subject of large-scale public controversies. Margera has been plagued by legal troubles related to his very public, tumultuous journey with substance use especially after the untimely death of Ryan Dunn—issues that contributed to his being excluded from most of the filming and final theatrical cut of Forever; other cast members, some of whom have likewise shared histories of drug use over the course of their careers, ostensibly attempted to intervene to have Margera involved contingent upon his own sobriety.[41]

Setting aside the complexities of addressing substance use—being outside the scope of this article—the Jackass crew’s handling of ongoing ordeals with Margera not only supports a sense of mutual responsibility for each other, but also for the effects their work has on the public. Notably since the show’s first airing on MTV, it has prominently featured disclaimers (that the hosts of StraightioLab compare rather disputably to trigger warnings) to not recreate its content. Said disclaimers failed to dissuade would-be copycats, contributing to the franchise’s move to film releases exclusively.[42] Out of the sources I’ve reviewed, the hosts of StraightioLab are the primary voices pointing out that much of the queer nostalgia for the show does seem to benefit from being viewed retrospectively, with the enlightenment of the present. That is not to say such identification with the franchise is invalid, but that it only mitigates the effects of homophobic and misogynistic harassment that may not have precisely resulted from Jackass, but were rationalized on the basis of it. If anything, this analysis serves to deepen the understanding viewers can have of this body of work, whose complexity and cultural impact has been largely disregarded until now.

Conclusion

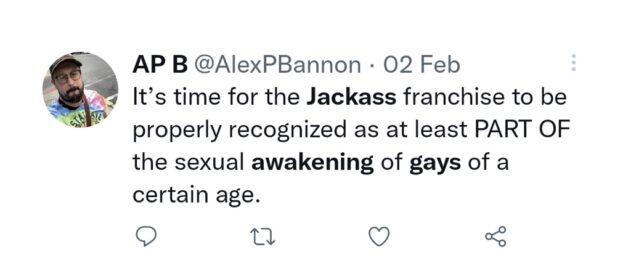

Jackass Forever introduced viewers to a series of new cast members, featuring comedian Rachel Wolfson as the cast’s first (and to date, only) female member, and multiple Black members including actor Eric Manaka and former rapper Jasper Dolphin. The visible diversity of this cast iteration compared to previous installments was commented on at the time of its release, with Knoxville stating the original crew “could have done a better job about incorporating more people, but we didn’t;” in the same interview, he marvels at the franchise receiving critical approval for the first time and emphasizes the centrality of male nudity to the series’ humor.[43] For all the trouble and labor dedicated to producing set humor, one wonders if the franchise’s so-called “anti-homophobic” intent might have been made more explicit to the betterment of 2000’s era culture and the aftereffects we feel of it today. Even so, the more “traditional” Jackass installments clearly hold great significance to the development of many queer individuals, with several of the Tweets I reviewed for this piece specifically naming them as an instigator of “gay awakenings” (figure 4).

One might also wonder if much of the franchise investment held by white gay men, specifically, can be credited in part to a sexually-charged consumer gaze that is as much adhered to whiteness and masculinity as it is to heterosexuality. My own view is that the relief of witnessing a masculinity that doesn’t entail a toxic level of seriousness—is indeed willing to “literally self-combust” in the words of Civeris—with actors taking physical risks not just in the name of heroism or bravado, but primarily in the name of absurdity and fun as has been suggested across the spectrum of sources I cite here, explains this fascination at least as plausibly The imagined boundary between the cultural realms of heteronormativity and queer art has long been taken for granted, despite their relatively recent and highly arbitrary definitions and applications. Making these connections between Jackass, its reception by queer viewers, and multiple works by queer theorists offers us an opportunity to erode the separation of queer art and media from “everything else,” which can unwittingly reinforce the strictures of normative identity.

[1] Eric Spitznagel, “The Stars of Jackass 3D On God, Cancer, and Homosexuality,” Vanity Fair, October 14, 2010. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2010/10/the-stars-of-jackass-3d-talk-about-god-cancer-and-homosexuality

[2] Lou Lumenick, “The Plot Sickens,” The New York Post, October 25, 2002, https://nypost.com/2002/10/25/the-plot-sickens/

[3] https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/jackass_forever; https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/jackass_the_movie

[4] Shannon Keating, “The New ‘Jackass’ Movie Is Funny, Thank Goodness,” BuzzFeed, February 8, 2022, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/shannonkeating/jackass-forever-review

[5] Joseph Earp, “’Jackass’ Has Always Been Deeply, Deeply Queer,” Junkee, July 26, 2021, https://junkee.com/jackass-forever-queer/303129

[6] Sean O’Neal, “This Is Why You’ll Never Stop Thinking About ‘Jackass,’” Men’s Health, February 2, 2022, https://www.menshealth.com/entertainment/a38678294/benign-violation/

[7] Jane Ward, Not Gay: Sex Between Straight White Men (New York: NYU Press, 2015), 130.

[8] Ibid, 34.

[9] Ibid, 125-126.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 6.

[12] Georg Civeris, Sarah Sherman, and Sam Taggart “Jackass w/ Sarah Squirm,” January 18, 2022, StraightioLab, presented and produced by George Civeris and Sam Taggart, podcast, MP3 Audio, 1:14:22, https://omny.fm/shows/straightiolab/jackass-w-sarah-squirm

[13] Ibid (0:40:25-0:41:05); emphasis added.

[14] Jess Thomson, “How Queer Folks Embraced the Positive Masculinity of ‘Jackass,’” Xtra Magazine, February 17, 2022, https://xtramagazine.com/culture/jackass-queer-positive-masculinity-218348

[15] Civeris, Sherman, and Taggart, 2022 (0:37:00-0:37:15); emphasis added.

[16] Ibid (0:37:20-0:37:50).

[17] Ibid (0:41:25-0:41:35).

[18] Thomson, 2022.

[19] Michel Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” in Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth (New York: The New Press, 1997), 136.

[20] Ward 2015, 37.

[21] Ibid, 25.

[22] Foucault 1997, 137.

[23] Civeris, Sherman, and Taggart, 2022 (0:43:53-0:44:09).

[24] Ibid (0:46:25-0:46:45).

[25] Halberstam, 2011 (139).

[26] Civeris, Sherman, and Taggart, 2022 (0:57:56-0:57:09 and 0:45:42-0:46:08).

[27] Ibid (0:55:58-0:56:11); emphasis added.

[28] Halberstam 2011, 140.

[29] Henry Giardina, Trans People Love ‘Jackass,’ and It’s No Wonder Why,” Into, February 8, 2022, https://www.intomore.com/film/trans-people-love-jackass-no-wonder/

[30] PFLAG National Glossary, s.v. “gender envy,” https://pflag.org/glossary/

[31] Niko Stratis, “’Jackass’ Made Me the Trans Woman I Am,” Bitch Media, February 4, 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/20231015043047/https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/jackass-made-me-the-trans-woman-i-am

[32] Ibid.

[33] Civeris, Sherman, and Taggart, 2022 (0:44:20-0:44:45); emphasis added.

[34] Ibid (0:44:04-0:44:41).

[35] Ward 2015, 69.

[36] Civeris, Sherman, and Taggart, 2022 (0:51:40-0:51:5); emphasis added.

[37] Ibid (0:40:25-0:40:44).

[38] Morgan Sung, “’Jackass’ and the Rise and Fall of Prank Content Online,” NBC News, February 5, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/viral/jackass-rise-fall-prank-content-online-rcna14000

[39] Louise Griffin, “How Disgraced YouTuber Sam Pepper Became a Viral TikTok Star: From Big Brother and Distressing Pranks to a Fully-Fledged Comeback,” Metro UK, January 14, 2020, https://metro.co.uk/2020/01/14/disgraced-youtuber-sam-pepper-became-viral-tiktok-star-big-brother-distressing-pranks-fully-fledged-comeback-12031928/

[40] Florence O’Connor and Zoe Haylock, “A Timeline of the David Dobrik Allegations and Controversies,” Vulture, June 27, 2022,

[41] Karla Rodriguez, “Bam Margera’s Turbulent Relationship with the ‘Jackass’ Crew, Explained,” Complex, September 29, 2022, https://www.complex.com/pop-culture/a/karla-rodriguez/jackass-bam-margera-beef-explained

[42] Jeremy Dick, “Steve-O Says Early Jackass Series Controversy was Justified,” Movieweb, June 25, 2022, https://movieweb.com/steve-o-says-jackass-backlash-was-justified/

[43] Andy Greene, “’It’s Funnier if His Cock is Out:’ Johnny Knoxville on the Past, Present, and Future of ‘Jackass,’” Rolling Stone, February 7, 2022, https://www.rollingstone.com/tv-movies/tv-movie-features/johnny-knoxville-jackass-forever-interview-1296064/amp/