Makenzie Coker

Makenzie Coker is a PhD Student in the American and New England Studies Program at Boston University. She is interested in material culture, fan studies, and popular culture, particularly the relationship between popular culture and academic scholarship. Her current research centers on romance novels as expressions of gendered sports fandom. She holds an MA in American History from The College of William & Mary and a BA in Medieval Studies from The University of Chicago.

“An Ideal Picture”:

The Fairbanks House, Landscape Transferware, and the Creation of Historical Canons

Introduction

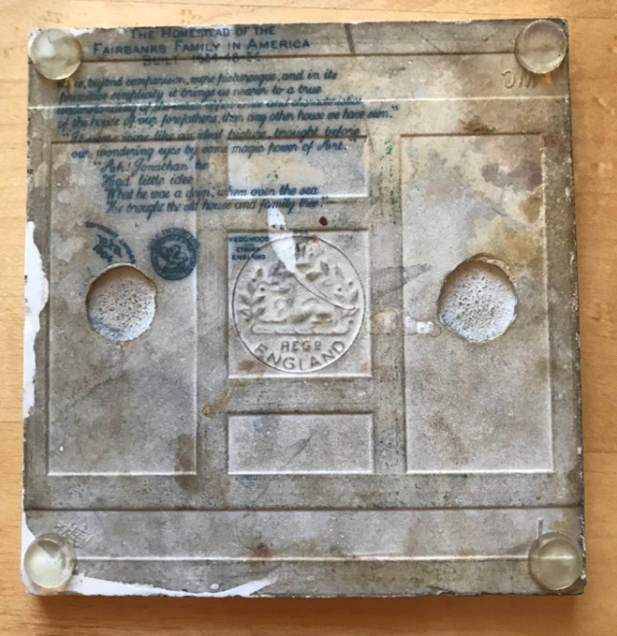

In 2015 I found a square, ceramic tile inside the kitchen wall of my apartment in Chicago. The experience was slightly surreal, a bit like acting out a mad-lib that produced unexpected items.[1] It was cool to the touch, 5 ¾ inches square, and felt heavier or perhaps denser than its 13.1 ounces. One side was glazed and featured an image of a house, finely drawn in blue on a white background; the other was unfinished and identified the house as “The Homestead of The Fairbanks Family in America” (figs. 1, 2). I had no idea who the Fairbanks family were, and I certainly didn’t recognize their house, but I was intrigued by that lack of recognition. Even without the identifying text on the back, there is a particularity to the tile’s visual detail that makes clear this is an image of a specific house, and because it is named, it seems to be representing itself, not serving as a model for a generic image. The identifying text, however, is on the back of the tile, not incorporated into the glossy finished side where it could easily be seen while the tile was in use or on display. One possible explanation is that whoever designed the tile believed that at least some people would, or should, recognize the Fairbanks house.

While it may not be named on the tile’s front, the subject (the Fairbanks House), manufacturer (Wedgwood) and importer (James McDuffee & Stratton Company) are all clearly noted on the back. This is not an object that is intended to be unexamined. It is participating in a broader conversation, and its markings act as citations of the other entities, objects, and ideas with which it is in dialogue. By researching each of these named parties, I traced the tile’s physical and conceptual journey to Chicago. It begins in mid-seventeenth-century Massachusetts, where the Fairbanks House stands and ages into venerable seniority over the next several hundred years. In the late nineteenth century, the Fairbanks House becomes the focus of familial mythmaking in the Colonial Revival style with the incorporation of the Fairbanks Family in America and the opening of the house as a museum. Next, I trace its transatlantic voyage to the Wedgwood factory in Etruria, England, to consider the history of landscape transferware production and collecting, and the distinct place it holds in material culture of the Colonial Revival. The Fairbanks House tile now returns to Massachusetts, no earlier than 1904, by way of James McDuffee & Stratton, importers of American historical ceramics. The tile and its many siblings then begin to circulate around the United States as an image in a catalogue or a souvenir. Through this circulation, the tile confirms the Fairbanks House’s cultural significance and place in the historical narrative. Entering Chicago, this particular tile engages with ideas of character creation and Americanization through consumption before coming to rest in an American home very different -at least in structural form – from the Fairbanks House, whose image it bore.

The images on ceramics such as this tile comprise a visual canon for the mythologized and Anglocentric version of American history created in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. An in-depth examination of the Fairbanks house tile reveals how such a canon may be constructed through the syncretic collaboration of individual actors pursuing their own goals. It also demonstrates the conditional and temporary nature of canonical inclusion.

The Fairbanks House

The Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts, was originally constructed in the seventeenth century for Jonathan Fairbanks and his family and is the oldest surviving timber frame house in North America. The central part of the house was built in stages between 1637 and 1656, with later additions made in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[2] The house is noteworthy for the degree to which parts of the structure remained unchanged from the seventeenth century. Dendrochronological testing has confirmed that timbers in the earliest section of the house date to between 1637 and 1641.[3] Through chance and the later generations’ lack of resources, more of the seventeenth-century house remained less altered than was typical, and even in the twentieth century it could boast “an extraordinary range of surviving features.”[4] Thus, the Fairbanks house grew in historical significance through a period of quasi-stasis. While the many well-preserved features of the house offer a wealth of information to historians, I would argue that the specifics of the house’s construction are less relevant to its inclusion in the popular colonial canon than the twentieth-century perception of its great relative age.[5]

Eight generations of the Fairbanks family lived in the house until straitened finances forced Rebecca Fairbanks to sell the property in 1895, although she was allowed to continue living there.[6] The new owner, John Crowley, planned to pull down the house and build new, but was willing to sell it “if an effort can be made to save it from destruction” as the house was already well known as a historical landmark.[7] Following an appeal in the Boston Evening Transcript “to arouse in the members of the patriotic societies here in Massachusetts a sense of the duty which they owe to themselves and to their country to try to preserve for Massachusetts this interesting relic of the colonial days,” Martha Codman, the widow of the artist John Amory Codman, and her daughter Martha Codman Karolik bought the property.[8] They then turned the house over to the Fairbanks Family in America in 1904.

The Fairbanks Family in America was incorporated in 1903 by J. Wilder Fairbank, who had been organizing large-scale family reunions over the previous several years and had a mailing list of over 3,000 Fairbanks descendants.[9] In their constitution the association claimed as their purpose “the acquisition of the title and the preservation of the Homestead of Jonathan Fairbanks in the town of Dedham,” as well as “the collection and preservation of all matters pertaining to the history of the Fairbanks Family in America.”[10] The constitution also calls for the study of the family’s history and publication of articles on that subject for the education of members. Membership was open to all descendants of Jonathan Fairbanks of Dedham, as well as their spouses, and dues were set at one dollar per family member, although it was hoped that those who could give more would.[11] The association sought to build community and connections between members by cultivating a sense of family identity through the creation of a shared historical narrative centered on the Fairbanks house. The goals laid out in the constitution also show a desire to disseminate this historical information more widely, both internally through the circulation of research among the many Fairbanks descendants spread across the United States, and externally by opening the Fairbanks house to the wider public as a museum in 1905.

There was no single important event or former resident that marked the Fairbanks house as a likely candidate for a museum.[12] It was instead selected for preservation because its inherent qualities – great age, relative lack of nineteenth-century renovations, and association with a single family- now marked it out as something rare and valuable. The establishment of both the Fairbanks House Museum and the Fairbanks Family in America was part of the intensifying interest in historical preservation and family heritage sparked by the Colonial Revival movement.[13] The movement, which began in the late nineteenth century and increased following the 1876 centennial, led Americans to reassess the early history of the U.S., particularly its domestic life or material culture.[14] The Colonial Revival broadened the scope of historical mythmaking and allowed the private home to take center stage in the nation’s memory alongside famous buildings and battles. There was an idea that what was best and essential to the American character had flourished most before industrialization during the “Age of Homespun.”[15] This conception of history held up the mythical, semi-self-sufficient farming household as the ideal Americans, rather than centering only on “Great Men.” Their way of living, as expressed in their houses and material culture, was seen as morally superior and truly American in character, and many Americans believed that they could shape the character of their own families and communities in that image through the style of their homes.

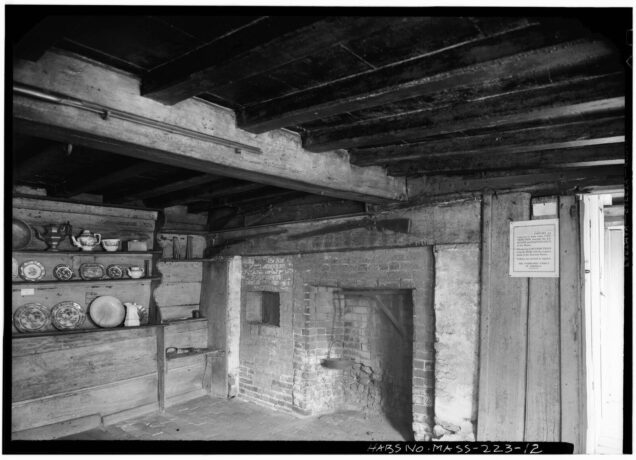

This focus on the domestic made American history useful and available to people in the present. While they could not go back and participate in the historical events of the past, they could adopt some version of colonial style in their homes and bring the past to them. The practical core of the Colonial Revival movement was, and remains, the use of design elements intended to reference or evoke the colonial period, in architecture, the decorative arts, and home décor.[16] There was no shortage of information for the would-be Colonial Revivalist of the late nineteenth century. Guidebooks, like Candace Wheeler’s popular Principles of Home Decoration with Practical Examples, gave advice on how to adapt the “colonial craze” to rented or recently built homes, while Wallace Nutting’s widely circulated catalogues offered not only furniture for sale, but also design inspiration in the form of carefully staged and photographed interiors.[17] The Fairbanks house embodied both the physical and the cultural ideas of the Colonial Revival espoused in this literature – it was very old, looked it, and had remained in the original family. The members of the Fairbanks Family in America who set up the museum were certainly aware of this, and they presented the house in the visual style of the Colonial Revival, complete with spinning wheel(s), hearth accoutrement, and displays of blue and white china (fig. 3).[18]

Tabletop Landscapes

The development of transfer printing techniques for ceramics in the 1750s made landscape tableware, previously reserved for those who could afford the cost of labor-intensive hand-painted goods, available to a much wider swath of the population.[19] Engraved plates were made from the desired image, inked, and printed on tissue paper, which was placed on the ceramic, transferring the ink. When it was dry, the tissue paper was dissolved in water and the ceramic was fired, glazed, and then fired again. Originally blue ink was used because it held its color best, but over time other colors were developed and more delicate tissue paper allowed for the transfer of more detailed images.[20]

English ceramic manufacturers began creating English landscape transferware in the second half of the eighteenth century. The vast majority of these scenes were rural, although there were a few urban views made.[21] Many of them featured a suitably grand central building, such as a castle, palace, or church. Although clearly important to the composition, these buildings did not dominate them. They were often placed at a distance framed by the landscape and vegetation with people or animals in foreground. Following the American Revolution, British manufacturers were required to contend with other countries, notably France, entering the tableware market in their former colonies.[22] As a means of maintaining their competitive edge, they began producing American transferware landscapes for export in the early nineteenth century. At first these American scenes were very similar to their British predecessors, focusing on historically significant or public buildings, with plenty of space given to the landscape. For example, the first platter produced by John Rogers and Son in the first half of the nineteenth century depicts the Boston State House (fig. 4). A plate of this design was actually found during archaeological work at the Fairbanks house.[23] Over time the American landscape transferware became more and more focused on the buildings, with less of the landscape, and fewer people, included in the image.

Wedgwood is an English manufacturer of fine china and porcelain founded in 1759 by Josiah Wedgwood. They are best known for their classically inspired jasperware and transfer printed creamware. Despite being an early pioneer of English transferware landscapes, Wedgwood was notably not involved in the earlier period of American scene tableware.[24] They made their first foray into the market with a pitcher for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, featuring views of the fair.[25] They would continue to produce American landscapes up to the present day.

Wedgwood’s partner for their major foray into American landscape tableware was Jones, McDuffee & Stratton (JMS), a Boston-based firm that specialized in imported china. The two were working together by 1881, and their successful relationship continued well into the twentieth century.[26] A series of plates and other tableware commonly referred to as Wedgwood Old Blue Historical is their primary contribution to American landscape transferware. The plates originally retailed for fifty and then thirty-five cents, roughly fifteen dollars today, which made them affordable for a growing number of Americans.[27] These plates were “excellent for the plate rail effect,” and were intended to be collectibles, falling within an established tradition of historical tableware collecting in America.[28] The first thirty-five “American Views” were produced in 1899 and sold very well, with more views introduced over time, but, because individuals or organizations could commission their own designs from JMS, the final number of designs, while estimated to be in the hundreds, is not precisely known.[29]

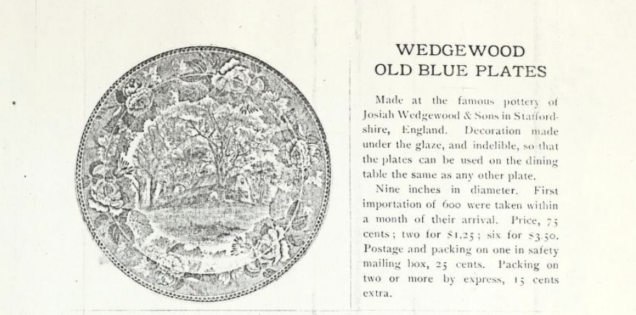

By 1904 the Fairbanks Family in America could count themselves among those organizations that had commissioned a plate in the Old Blue Historical line. In November of that year an issue of Ye Fayerbanke Historial, the periodical published by the association, offered mail order Fairbanks House “Wedgewood [sic] Old Blue Plates” of a very similar design to the tile along with pictures, postcards, paperweights, and various other ephemera (fig. 5).[30]

The author’s choice to highlight the connection to Wedgwood, a British manufacturer, in the listing for a product that trades so heavily on its Americanness indicates a belief that the benefits of an appeal to connoisseurship would outlay any perceived contradiction. The advertised discount on a six-piece set as well as the emphasis on the “indelible” glaze protecting the designs also point to an understanding, or at least hope, that the plates would be used as tableware, in addition to their decorative function. Taken as a whole, the text positions the plates as refined but practical editions to any home.

JMS was also known for their annual calendar tiles, manufactured by Wedgwood.[31] They were rectangular and featured a historical American scene on the reverse, with a small hole in one end, presumably so they could be suspended or affixed to the wall. These were given away to customers by JMS as advertising in much the same way later businesses would give out paper calendars. In 1910 alone they distributed 12,000 of them, which gives some sense of the company’s scale.[32] They also produced a different kind of calendar tile for sale. These were square, one-sided, and each had a scene representing a single month, such that a full year would comprise twelve tiles.[33] So the tile bearing an image of the Fairbanks house was engaging with a long tradition of historical blue and white landscape transferware – a tradition that aligned with the decorative and commercial inclinations of the Colonial Revival, as well as with the Fairbanks House Museum’s presentation of itself as the ideal early American home.

The intended use of this tile is somewhat ambiguous. It is the same size as other tiles produced by Wedgwood around this time, and the depressions on the back side indicate that it could be functionally installed as a wall tile. However, this would render the text on its back permanently inaccessible and the absence of grout residue on the tile rules that out in this particular case. The tile may have been displayed on a plate rail or mantel, although its unfinished edges might imply this was not the original intent. It was most likely used as a trivet to protect tables or counters from contact with hot dishes. The tile could have been used as is, or it could have been placed in a frame with legs. These frames range from simple, twisted, wire, to elaborately decorated silver (fig. 6).

Although the image is recognizable as the Fairbanks House to those who have seen it before, it is only textually identified on the back, unglazed side. The back of the tile is stamped with both the Wedgwood and Jones, McDuffee and Stratton marks. Some tiles with this design, although not this particular one, state that they were made for the Fairbanks Family in America.[34] There are also several quotations referring to the Fairbanks house and family printed in an elaborate looping script on the back of the tile (fig. 2).

THE HOMESTEAD OF THE

FAIRBANKS FAMILY IN AMERICA

BUILT 1634-48-56

“It is, beyond comparison, more picturesque, and in its

primitive simplicity it brings us nearer to a true

understanding of the actual appearance and characteristics

of the house of our forefathers, than any other house we have seen.”

“It seems more like an ideal picture, brought before

our wondering eyes by some magic power of Art.”

Ah! Jonathan he

Had little idee

“What he was a doin, when over the sea

He brought the old house and family tree.”

The quotations come from a book on the Fairbanks family by J. Wilder Fairbanks, which is itself excerpting from Alvin Lincoln Jones’ 1894 book Old Colonial Homes.[35] They can be read as a justification for the inclusion of the Fairbanks house in the New England Views series. It is worthy of such visual commemoration because it is a very old, very well-preserved example of a true American house, credit for which was given to the Fairbanks family.

There are no people or animals visible, no nearby houses or signs of other life. The house is presented as existing out of time, clearly old, but not specifically dated to either the past, present, or future. Other more-or-less contemporary images of the house– photographs used for postcards and a Childe Hassam painting, contextualize the house with the inclusion of people and the surrounding built landscape (fig. 7). They place the house firmly in the present day of their creation, depicting it as a real place rather than an idealized symbol. The tile shows the house as an icon, contextualized by the rise of the hill and the towering grandeur of the trees that overtop it and fill in the sky. While its clear geometric lines and recognizable architectural features mark it as manmade and therefore not of the landscape it does seem to be on that scale of time.

The image used as the referent for the Fairbanks house transfer was a photograph taken in 1899 by the Detroit Publishing Company.[36] Detroit Publishing was a major American creator of postcards in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and were known for their photochrome work.[37] While there are several photographs of the house from this angle which appear on postcards, the shadows of the branches on the roof point to this one. This specific image may not have been published as a postcard, or if it was, it has not survived well. It is not clear who provided the image – the Fairbanks Family in America, Jones, McDuffee & Stratton, or Wedgwood. The degree to which this image was selected for its characteristics as opposed to being a choice of convenience cannot be determined either. Other plates produced by Wedgwood for JMS seem to feature postcard images as well, so the image used for the Fairbanks house tile would appear to fall within the normal practice, whatever the particulars of its selection.

Postcard images may have been used on relatively mass-produced items, such as the Old Blue Historical tableware for reasons beyond convenience. The images were familiar to customers in their style and composition, even if the subjects themselves were new. It was also much more cost effective to buy or license existing images than to pay a photographer to take new ones. A particularly humorous example that showcases both the postcard roots of these images, and the general cost-cutting and lack of care that went into their production, is the view of the Massachusetts State House in Boston. The image, which looks like a postcard complete with identifying text, was simply placed directly on the center of the plate, without the usual effort at blending the edges.[38] Another version of this plate featuring the exact same image, but now with a fully extended background, was also made.

Postcards had been rising in popularity during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as the U.S. government gradually opened their publication to commercial ventures.[39] They were not only the vehicles for short notes, but also souvenirs and mementos of the past and of places visited or visited by friends.[40] They indicate a connection, “I was there” or “someone I know was there”; postcards were a recognizable type of image that could travel and circulate. In her article “Copley’s Cargo,” Jennifer Roberts argues that certain kinds of images can more easily be conceptualized as moveable within a given culture.[41] She claims that the formal features that convey this sense of mobility can be, and in some cases have been, isolated and used to intentionally construct movable images. The use of postcard images, and the fact that these ceramics were being shipped internationally seem to resonate with her underlying premise. The plates, trivets, and in particular the calendar tiles, all resemble ceramic postcards. There is overlap in the images that were used, but they also share a similar shape and scale. There are practical reasons for this. Ceramics in these shapes were easier and more efficient to pack and ship. They were not so large as to be overly costly and the similar size no doubt made transferring the images easier. Their shared physical properties might also indicate other shared functions, however. Ceramic landscapes were also images that circulated and had a long history of being collected and displayed as souvenirs.[42] Perhaps their resemblance to and use of postcard images strengthened the qualities that let them do so, or perhaps it is merely an example of convergent evolution.

Either way, plates and tiles with their scenes of New England history, including the Fairbanks house sold well and spread those images across the country. While people at the turn of the century had access to many more images than in centuries past, they were still far, far, fewer than today. Finding out what a specific place looked like took work, and perhaps a certain amount of luck. A company or organization in the position to influence which images people did see had the opportunity to take an active role in shaping the popular historical canon by constructing its visual component.

In this case there are three organizations, the Fairbanks Family in America, Jones McDuffee & Stratton, and Wedgewood, each with their own individual goals, who combined to promote a particular narrative of American History. This narrative was Anglophilic and centered on New England, and to a lesser extent the other British colonies now part of the United States. The version of American history visualized by the Old Blue Historical plates privileged the English influence on the population of America and culture, language, and architecture. This narrative was constructed to the exclusion of the early French, Spanish, and Dutch presence, not to mention later immigrant groups. It also completely ignored the presence of Native and Black Americans, both free and enslaved, two groups who played a very large role in the history of New England, the region these plates most focused on. The hegemonic American folk culture and perception of the past argued for by the Colonial Revival movement as embodied in the Old Blue Historical Plates elides the difference between American and Anglo-American. All the truly important parts of early American history and culture are traced or tied to the English.

All three major parties involved in the production of the Fairbanks House tile had reason to support this narrative. The Fairbanks House was a building originally constructed in an English vernacular style, by an English family who had only recently come to America. The tableware depicting it was commissioned by a group, the Fairbanks Family in America, descended from that original English family and interested in presenting the house in line with Colonial Revival ideas. The firm that imported and sold the plate in America was based in Boston, and the company that produced it was located in England. Of the three, the Fairbanks Family in America had the most ideological intent, but even they were most concerned with their own financial benefit and inclusion in the narrative, rather than its shape as a whole. It is an effect that builds up in the aggregate from all the individual interactions between cultural, personal, and financial interests.

Chicago

Chicago in the early twentieth century was in many ways the antithesis of this Anglocentric view of America, founded after the Revolution and outside the geographic bounds of New England. It was a center for transportation, meat processing, and industry with a modern downtown core, almost entirely rebuilt after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 blazed a four-mile strip through it.[43] By 1910, over 70% of the city’s population were either foreign-born immigrants or their children. Over the next several decades, it also became one of the major destinations for African Americans during the Great Migration.[44] While Chicago represents many key aspects of what might be called the “American Experience,” these are not aspects reflected in the idealized myth of early America. Unlike citizens along the Atlantic Coast, residents of Chicago did not find physical reminders of the mythologized colonial past in the day-to-day geography of their city. The presence of objects like the Fairbanks House tile in early twentieth-century Chicago residences is therefore suggestive of the ways in which the material culture of Colonial Revival was becoming associated with broader concepts of American identity.

The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 gave millions of Americans access to this colonial imaginary and spread the idea beyond its historical geographic bounds by quite literally bringing it to them. There was significant Colonial Revival influence in the fair’s architecture and exhibits, particularly the design of the state buildings which housed exhibits and host events.[45] Visitors could tour recreations of Mount Vernon (Virginia), Independence Hall (Pennsylvania), John Hancock House (Massachusetts), or one of eighteen other colonial inspired state buildings. They could eat at the New England log cabin, watch demonstrations of colonial handcrafts on the Midway Plaisance, or join the 800,000 visitors who viewed the Massachusetts exhibit of historical objects from the Essex Institute’s collection.[46] The fair offered visitors a historical narrative that was both vivid and tangible. It may have been fleeting, but its presence was real.

The Fairbanks House tile is both a product of the same strain of Anglo-American historical narrative, and a means for its further spread. Its presence in Chicago indicates that some residents of the city were engaging with this canon beyond the bounds of the fairground. Patricia West discusses the complicated directionality of this engagement, most notably for immigrants but also native-born Americans without deep familial connections to the past of a place.[47] Anglo-American reformers concerned about changing demographics saw Colonial Revival architecture and interiors as a means of maintaining their cultural hegemony. They believed immigrants, particularly children, could be Americanized through the imposition or inculcation of the desire for the “correct” kind of material culture.[48] However, the adoption and use of that material culture allowed people previously excluded from the colonial mythos to expand perceptions of who or what was legible as “American.” Purchasing and displaying ceramics like the Fairbanks House tile could be seen as a marker of participation in this aspect of American-ness.[49] Residents of Chicago may not have lived in New England, but they too could display blue and white china to make their homes in the image of those idealized colonial ones, at least symbolically.

The iconography of the ceramics may also have had some symbolic function of its own. In this case, the tile depicts the Fairbanks House, a building commemorated specifically for being a very well-preserved old house. It represents the ideal American home, an abstraction that is reinforced by the absence in this particular image of any context with regards to time or location. Thomas Denenberg refers to Colonial Revival objects and images as having a quasi-religious valence. In some cases, they can take on a “totemic” quality and mark or bless the space around them.[50] There is some nebulous sense in which the image of the Fairbanks House may transform the house in which it resides, its presence conferring the identity of a true American home in spirit if not in physicality.

Conclusion

When Mrs. Paul J. Urban wrote “Our American Story” illustrated by Wedgwood plates in 1957, the Fairbanks House was there, alongside the landing of the Mayflower, the surrender of Lord Cornwallis, and an image of the Massachusetts State House with similar earlier plate found at the Fairbanks house.[51] The Fairbanks Family in America had successfully written their house into the national narrative which they once consumed, but the house’s place in that canon was only temporary. Although the Wedgwood Old Blue Historical Fairbanks House plates and tiles still circulate through antique shops and online auctions, I had never heard of it before finding my tile. They still convey a historical narrative, but it is increasingly one of their own moment of creation rather than the past they were created to represent. There is a fascinating sense of circularity at play with this tile. It was once in an apartment in Chicago where it memorialized a house in Massachusetts, and is now in a house in Massachusetts, where it reminds me of my apartment in Chicago. Over a hundred years on and it continues to serve as an anchor for memories and a tool for transforming a space to a home.

[1]It was the end of the quarter, and I was admittedly quite sleep-deprived at the time.

[2] Abbott Lowell Cummings, The Fairbanks House: A History of the Oldest Timber-Frame Building in New England, 2nd ed. (Boston: Fairbanks Family in America; New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2003), https://archive.org/details/fairbankshousehi0000cumm.

[3] D.W.H. Miles, M. J. Worthington, and Anne Andrus Grady, Development of Standard Tree-Ring Chronologies for Dating Historic Structure in Eastern Massachusetts, Phase II, Abr. ed. Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities and Oxford Dendrochronology Laboratory, 2002, https://www.dendrochronology.com/fhd-1.html.

[4] Cummings, The Fairbanks House, 3.

[5] For an in-depth architectural examination of the Fairbanks House, see Abbott Lowell Cummings, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979).

[6] Cummings, The Fairbanks House, 41.

[7] Mrs. Nelson V. Titus, “A Last Appeal for the Fairbanks House,” Boston Evening Standard, April 3, 1897, part two, last edition, https://books.google.com/books/newspapers/.

[8] Titus, “A Last Appeal.” Cummings, The Fairbanks House, 41. Cummings notes that the Codmans’ purchase of the house was really more of a loan, as the Fairbanks Family in America mortgaged it back to them on a five-year note after taking possession.

[9] Charles Bridgham Hosmer, Presence of the Past: A History of the Preservation Movement in The United States Before Williamsburg (New York: Putnam, 1965), 116, https://archive.org/details/presenceofpast00hosm.

[10] J. Wilder Fairbank, “With the Historian: La Raison D’Etre,” Ye Fayerbanke Historial 1, no. 1 (1903), 35, https://archive.org/details/yefayerbankehist12bost.

[11] Fairbank, “With the Historian,” 35.

[12] There are several historically prominent Fairbanks descendants including Charles W. Fairbanks, the twenty-sixth Vice-President of the United States, but none of them ever lived at the Fairbanks House.

[13] Richard Guy Wilson, introduction to Re-Creating the American Past: Essays on the Colonial Revival, eds. Richard Guy Wilson, Shaun Eyring, and Kenny Marotta (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 6. See also Hosmer, Presence of the Past, 115.

[14] Wilson, Re-Creating the American Past, 5. See also Kenneth L. Ames, introduction to The Colonial Revival in America, 1st ed., ed. Alan Axelrod, (New York: Norton, 1985), 9.

[15] The “Age of Homespun” was an idea developed by the Rev. Horace Bushnell in an 1851 address at the Litchfield, CT, county centennial. William Butler says of this, “Residents [of Litchfield] did not rely on documentary evidence for their colonial restorations, but based their work instead on traditions and memory, romanticizing, sentimentalizing, and idealizing the image of the colonial style,” William Butler, ”Another City upon a Hill: Litchfield, Connecticut, and the Colonial Revival,” in The Colonial Revival in America, ed. Alan Axelrod, (New York: Norton, 1985), 36. For a fuller discussion of the idea’s development see Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, introduction to The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth, (New York: Vintage Books, 2002).

[16] Patricia West, Domesticating History: The Political Origins of America’s House Museums, (Washington D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999), chap. 2 sec. 1, Kindle.

[17] Candace Wheeler, Principles of Home Decoration with Practical Examples (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1903), 163, https://archive.org/details/principlesofhome00whee. Thomas Andrew Denenberg, Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 66.

[18] See also this postcard of the Fairbanks House Museum Living Room, c.1910, https://www.ebay.com/itm/296144676131, which is staged very similarly to Wallace Nutting, Trimming the Pie, 1910s, black and white photographic print – hand tinted, 7×9 in, Wallace Nutting photographic collection, Historic New England, https://www.historicnewengland.org/explore/collections-access/gusn/223470/

[19] Jeanne Morgan Zarucchi, The Material Culture of Tableware: Staffordshire Pottery and American Values (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), 19.

[20] Arthur Wilfred Coysh and Frank Stefano Jr., Collecting Ceramic Landscapes, British and American Landscapes on Printed Pottery (London, England: Lund Humphries, 1981), 12.

[21] Coysh and Stefano, Collecting Ceramic Landscapes, 39.

[22] Zarucchi, The Material Culture of Tableware, 19.

[23] Travis Parno, “Lab Update: On Cross Mending…,” Archaeology at the Fairbanks House, April 22, 2001, http://fairbanksarchaeology.blogspot.com/2011/04/lab-update-on-cross-mending.html.

[24] Christina H. Nelson, “Transfer-Printed Creamware and Pearlware for the American Market,” Winterthur Portfolio 15, no. 2 (1980): 93.

[25] Coysh & Stefano, Collecting Ceramic Landscapes, 69.

[26] Coysh & Stefano, Collecting Ceramic Landscapes, 69.

[27] Keith A. McLeod and James R. Boyle, “Wedgwood and the Boston Connection,” Alexis Antiques, www.alexisantiques.com/links/jms.php, likely transcribed from The Heritage of Wedgwood (Elkins Park, PA: Wedgwood International Seminar, 1998) by the same authors.

[28] McLeod and James R. Boyle, “Wedgwood and the Boston Connection.” Edwin Atlee Barber, Anglo-American Pottery: Old English China with American Views, A Manual for Collectors, (Indianapolis: Press of The Clay-Worker, 1899).

[29] Coysh and Stefano, Collecting Ceramic Landscapes, 71.

[30] Ye Fayerbanke Historial 1, no. 3 (1904), 19-20, http://archive.org/details/yefayerbankehist13unse

[31] John Connolly, A Century-Old Concern, Business of Jones, McDuffee & Stratton Co. Founded by Otis Norcross, the Elder, in 1810, Unbroken Record of Growth and Progress, the Largest Wholesale and Retail Crockery, China and Glassware Establishment in the Country … (Boston: G.H. Ellis, Printers, 1910), 28, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433023109378&seq=1.

[32] Coysh and Stefano, Collecting Ceramic Landscapes, 69.

[33] Julian Barnard, Victorian Ceramic Tiles (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1972), 83.

[34] Wedgwood for Fairbanks House, The Homestead of The Fairbanks Family in America, c.1904, https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/1904-flow-blue-wedgwood-plate-1723218474

[35] John Wilder Fairbanks and Alvin Lincoln Jones, The Old Fairbanks House, 1908.

[36] Detroit Publishing Co., Old Fairbanks House, Dedham, Mass., photograph, c.1899, https://www.loc.gov/resource/det.4a07130/.

[37] “Detroit Publishing Company – About this Collection,” Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/collections/detroit-publishing-company/about-this-collection/.

[38] Wedgwood for Jones McDuffee & Stratton Co., The State House, Boston, c. 1899, https://www.ebay.com/itm/Wedgwood-Etruria-Blue-White-Historical-Boston-Plate-State-House-1899-/253703408311

[39] “Development of the Modern Postcard,” Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/det/development.html.

[40] Maribeth Keane, “When Postcards Were the Social Network,” Collectors Weekly, November 20, 2008, www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/an-interview-with-vintage-postcard-collector-ann-waidelich/.

[41] Jennifer Roberts, “Copley’s Cargo,” American Art 21, no. 2 (2007): 20-41.

[42] Coysh and Stefano mention that some of the American Landscapes not sold in Britain did end up there, brought back by travelers. Coysh and Stefano, Collecting Ceramic Landscapes, 71.

[43] Robert G. Spinney, City of Big Shoulders: A History of Chicago (Ithaca: Northern Illinois University Press, 2020), 92, ProQuest Ebook Central.

[44] Spinney, City of Big Shoulders, 111.

[45] Susan Prendergast Schoelwer, “Curios Relics and Quaint Scenes: The Colonial Revival at Chicago’s Great Fair,” in The Colonial Revival in America, ed. Alan Axelrod (New York: Norton, 1985), 195.

[46] Schoelwer, “Curios Relics and Quaint Scenes,” 204

[47] Patricia West, Domesticating History, chap. 2, Kindle.

[48] William B. Rhoads, “The Colonial Revival and the Americanization of Immigrants,” in The Colonial Revival in America, ed. Alan Axelrod, (New York: Norton, 1985).

[49] Patricia West refers to this as joining “consumption communities.” Patricia West, Domesticating History, chap. 2, sec. 5, Kindle.

[50] Denenberg, Wallace Nutting, 5.

[51] Mrs. Paul J. Urban, “English Blue Printed Wear,” Second Wedgewood International Seminar Minutes (Merion PA, Wedgwood International Seminar, 1957), 46-54, https://issuu.com/josiahw/docs/1957/46.