The Quiet Revolution

The 2023 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Claudia Goldin for her research on the changing role of women in the workplace. As Noah Smith highlights in his blog, Goldin’s work provides a “coherent narrative” that explains the historical trends in women’s labor market outcomes by exploiting novel datasets and synthesizing seemingly disparate facts and theories. Here, I want to focus on Goldin’s 2006 Ely Lecture, as I believe it provides a great glimpse into the economist’s wide ranging work.

Two Major Trends

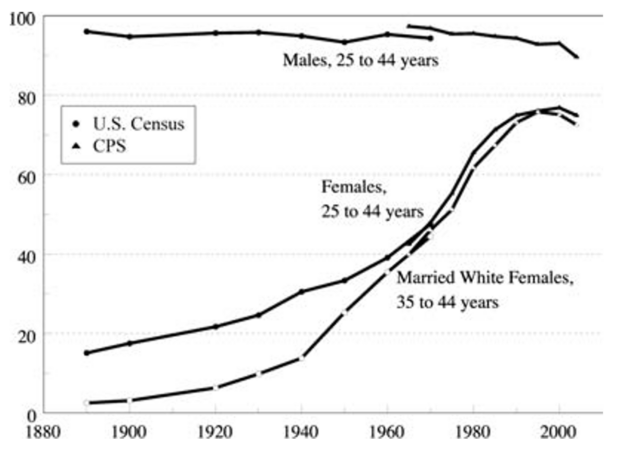

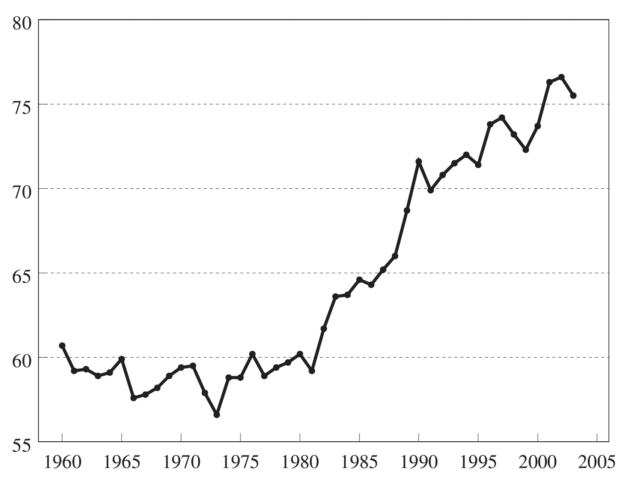

Before diving into the paper, it is useful to highlight two major changes in the labor market outcomes for women. First, there was a gradual increase in the female labor force participation (FLFP) rates since the 1900s. Second, there was a sudden increase in the relative earnings of women during the 1980s. Goldin’s work sheds light into the underlying mechanism behind these two trends. As we will see, the difference in the way the two series increased is central to Goldin’s argument.

Evolution vs. Revolution

Goldin divides the 20th century into four phases: (i) 1900s to 1920s, (ii) 1930s to 1950s, (iii) 1950s to 1970s, and (iv) late 1970s onwards. She describes the first three as evolutionary and the last one as revolutionary (namely, the “Quiet Revolution”). It is important to distinguish between the two terms: evolution refers to a consistent but moderate change whereas revolution refers to a sudden and rapid change. While the gradual increase in the FLFP is a consequence of various socioeconomic evolutionary forces, the rapid ascent in women’s earnings after 1980s is a result of revolutionary forces across specific dimensions like horizon and identity. For now, don’t worry about what these terms mean.

Phase 1: 1900s to 1920s

Since most jobs in the 1900s were dangerous and long in hours, there was a social stigma against women working after they were married. It was the man’s responsibility to provide income for his family, while the wife had to maintain their household. Such a socioeconomic environment meant that women could not benefit from the gains of economic growth. That is, the stigma against women working meant the supply of female workers was virtually non-responsive to increases in the demand for labor (and so wages). Yet, we can see the FLFP rise moderately during this period in Figure 1. Goldin deduces this to be caused by the rise in office clerical roles. These “nice jobs” reduced the stigma of women working, which allowed their supply to become more flexible to wages.

Phases 2 and 3: 1930s to 1950s, 1950s to 1970s

Since the phases lie on a continuum, it is hard to pinpoint what caused the transition from one phase to another. Intuitively, it’s easier to think about the transitions as the result of the aggregate effects of a novel change in the previous period. Here, the aggregate effects of rising office jobs in the 1900s combined with the abolishment of marriage bars in the 1940s resulted in many married women entering the work force during Phase 2. Additionally, the introduction of scheduled part-time work meant women did not have to make the difficult decision of committing to a full-time job. Instead, they had more flexibility in choosing how much they worked and when they worked, which increased their responsiveness to increases in (hourly) wages.

The aggregate impact of the increased clerical roles and part-time jobs led to a gradual change in the social norm, resulting in more married women entering the labor market in Phase 3. This was complemented by an increased demand for labor during the economic boom of the 1950s, which resulted in women staying in the labor force for much longer than they had originally anticipated. This is not surprising, as they had formed their expectations growing up in Phase 2, witnessing their mothers work intermittent jobs with no plans of a long-term career. However, their experiences had set the stage for the new generation and their quiet revolution.

The Quiet Revolution: Late 1970s Onwards

Let’s take a moment here to summarize the socioeconomic evolutionary forces that resulted in the gradual increase in the FLFP. The 1900s was characterized by a strong social stigma against married women working dangerous and arduous jobs. However, the rise of office jobs and scheduled part-time work along with anti discriminatory legislation like banning marriage bans resulted in women entering and staying in the work force at greater rates.

Nevertheless, during this period of consistent improvements in the FLFP, women’s relative earnings to men remained stagnant (Figure 2). This can be largely attributed to the nature of work performed by women (office workers, part-time gigs, etc.), which provided them with no incentive to invest in higher education and little on-the-job learning. However, this drastically changed during the quiet revolution for two main reasons.

First, young women in the late 1970s had an expanded horizon: they were able to better predict their future work lives after observing the progress made by women in Phase 3. Second, the changing role of women in the workforce added a new dimension to their identity. For example, Goldin notes that women increasingly began to value financial success and career recognition in the late 1970s. These forces were complemented by the invention of the pill, which allowed women to delay their marriage and focus on their careers first. Naturally, these changes resulted in a rise in women majoring in career-oriented subjects and transitioning from jobs as nurses and social workers to careers as doctors and lawyers. Goldin attributes these changes, in addition to continued anti-discriminatory legislations imposed in the labor market, to drive the reduction of the gender wage gap starting in the late 1970s.

With such revolutionary forces in action, women’s role in the workforce fundamentally changed – achieving a degree of parity with men that was seemingly implausible at the start of the century.