The Epidemic of Disillusionment: And How You Can Overcome It

What is the Epidemic of Disillusionment?

A lot of economics students, early on in their undergraduate studies, become disillusioned with the subject. Talking to my peers and reflecting on my personal experiences, I believe a driving reason for this “epidemic” is the pedagogical methods used in lower-level (and many times upper-level, too) undergraduate economics courses. In particular, the focus on teaching abstract theories siloed from a discussion of real-world data substantiating these theories turns students away from economics. However, I am not here to denounce nor praise the already established pedagogical methods. Instead, I want to show you that theory and empirics are not actually separate entities isolated from one another. Quite the opposite, theory and empirics combine to facilitate economic research and better our understanding of the world. This insight, hopefully, should provide a remedy for the disillusionment you might be facing.

The Theory-Empirics Cycle

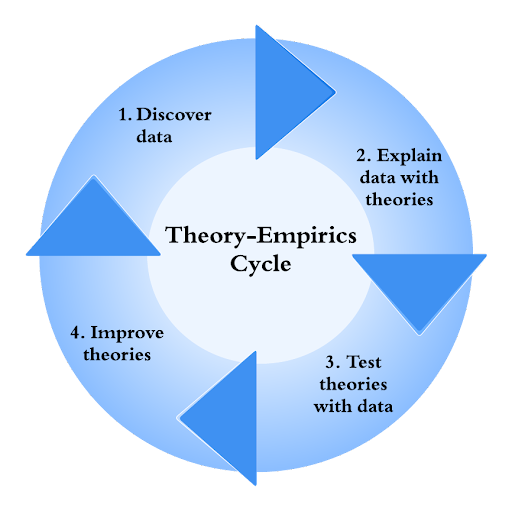

I would be doing the discipline wrong if I did not attempt to boil down complex relationships into simplified diagrams. So, to me, the dynamics between theory and empirics can be illustrated as follows:

The caveat of the above diagram is that it is a continuous cycle that might not have a clearly defined end. That is, it is very rare that you will find a theory that is not being actively tested and improved upon. Why? Because the assumption of ceteris paribus does not hold in the real world, and you can examine a theory in an infinite number of ways. Thus, you will rarely find a theory that (legitimately) reaches sweeping conclusions. If this bothers you, what proceeds probably won’t cure your dissatisfaction with the discipline. However, if the endless possibilities to test theories and continuously improve them excites you, I might have a solution for your disillusionment.

Mapping the Trajectory of the “Crowding In” Hypothesis

If you have taken an introductory macroeconomics course, you probably already have a strong intuition of what it means when economists say, “government spending crowds out private investment.” In a nutshell, the logic boils down to supply and demand dynamics: the government increases the demand for loanable funds → the price of loanable funds (i.e., the interest rate) rises → private investment reduces.

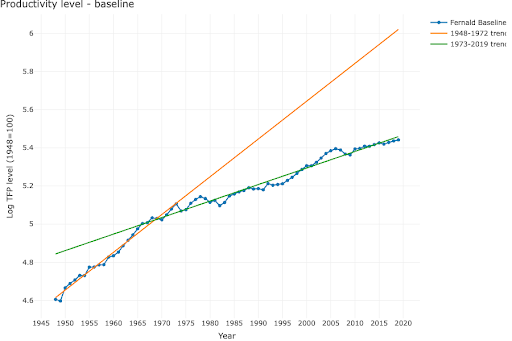

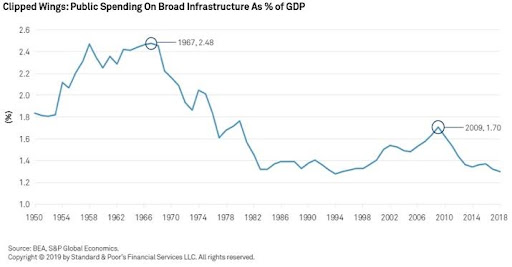

However, the striking correlation between the dramatic slowdown of productivity in the early 1970s (figure 1) and the stagnating investment in public infrastructure since the late 1960s (figure 2) caused economists to start questioning the dynamics between public investment and private investment. In his influential paper, Aschauer (1989) postulates that government expenditure towards public infrastructure in the USA increases the marginal product of capital by complementing private capital in the “production and distribution of private goods and services,” thereby stimulating (i.e., “crowding in”) private investment. This seems fairly intuitive: better roads and bridges reduce transportation costs, more efficient energy infrastructure reduces the costs of running factories, and increased public recreational infrastructures boost labor productivity.

In this case, Figures 2 and 3 can be seen as stage 1 of the theory-empirics cycle, while the Aschauer (1989) paper can be interpreted as stage 2 of the cycle. Just as there are various scenarios (such as different geographic locations, political characteristics, etc.) in which a theory can be put to test, there are multiple methods to test a theory. For the sake of simplicity, I will explore how a small segment of the time series literature reacted to Aschauer (1989) (i.e., stages 3 and 4 of the theory-empirics cycle).

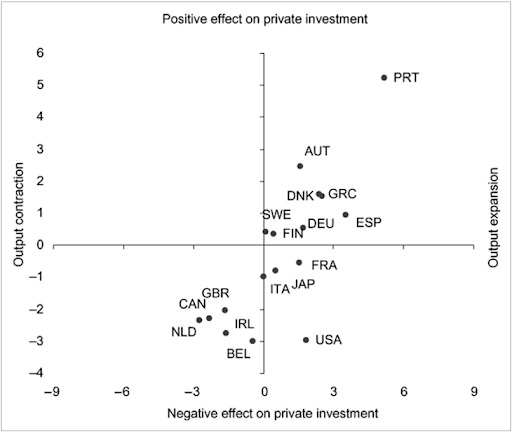

In response to Aschauer (1989), numerous papers tested the “crowding in” hypothesis in various settings using a vector autoregression (VAR) framework. In essence, this econometric methodology allows economists to evaluate how certain variables (like private investment) respond to shocks on other variables (such as increased public investment) over time. Notably, Afonso and St. Aubyn (2009) extend Aschauer’s original “crowding in” hypothesis to 14 European Union countries, Canada, and Japan. The authors find that the dynamics between public investment and private investment vary from country to country. While public investment crowded out private investment in Belgium, Ireland, Canada, the UK, and the Netherlands, it crowded in private investment in Austria, Germany, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden (figure 4). What is different between these two groups that caused public investment to have a different effect on private investment? Is it because countries with lower GDP invest more in infrastructure and, therefore, benefit from crowding in? Or maybe some countries’ governments are more supportive of private businesses? This is, in part, what Bahal et al. (2018) explore. By implementing a structural vector error correction model (SVECM), the long-run counterpart of the VAR framework, the authors show that following the “pro-business reforms of the early 1980s and the structural reforms of 1990s,” there was a shift in the dynamics of public and private investment in India, with public investment increasingly crowding in private investment! To be sure, none of these papers present sweeping conclusions. The literature on the “crowding in” hypothesis is still evolving, with researchers finding innovative ways to test the theory in different circumstances.

Okay so Now What?

Hopefully the theory-empirics cycle and the trajectory of the crowding in hypothesis has convinced you of the existence of the give-and-take relationship between economic theory and real-world data. However, simply acknowledging this relationship is probably not a strong enough remedy to your disillusionment. So where do you go from here? I think the best solution is to actively involve yourself with the theory-empirics cycle. If you come across an article describing cool data, ask yourself if the data is explained by existing economic theory? Does the data contradict existing economic theory? This is fairly doable as an undergraduate student and will make you well-versed with stages 1 and 2 of the theory-empirics cycle. Getting involved in stages 3 and 4 is a trickier task, because testing and improving economic theories often requires the use of rigorous econometric methodology and takes a lot of time. I would leave this to the actual economists. However, you can always take the first steps by taking courses in econometrics and reading up on how the current economic literature is testing and improving theories that excite you.

Written by Vignesh Somjit