Food Mapping in the SOWA Market

Students in Dr. Karen Metheny’s Summer Term course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) are contributing guest posts this month. Today’s post is from Becca Berland.

Food mapping is not something that your typical graduate student does on a daily basis. I’ll admit that I have never even heard of the concept before taking Dr. Karen Metheny’s Anthropology of Food class this summer. But as I’ve learned more about various ethnographic methods of study, I do think that food mapping has the ability to bring something different to the table.

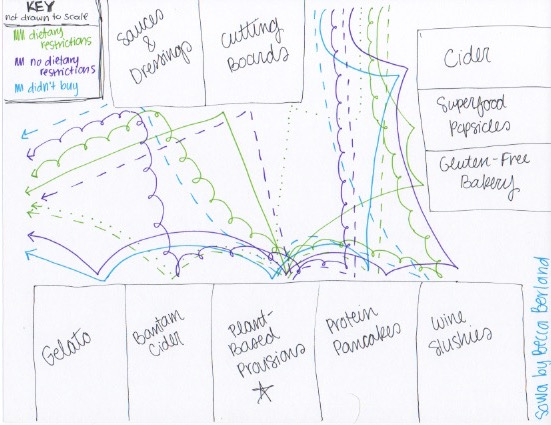

For my food mapping project, I decided to observe and map out a corner of the SOWA Farmer’s Market in the South End of Boston. I’ve been helping man the Plant-Based Provisions (PBP) table this summer, so I used this opportunity to track the footpaths of three different groups of people who visited our stall. I chose to divide the customers I observed the following groups: those who expressed their dietary restrictions, those who had no dietary restrictions (or didn’t express them), and those who stopped at the table but didn’t purchase anything.

Since PBP focuses on vegan, dairy-free, and allergen-free sweet treats, many customers choose to tell us about their dietary restrictions when making friendly conversation. Most are either vegan, lactose intolerant, gluten intolerant, or attempting the Whole 30 diet. We also get customers who are looking for a healthier, naturally sweetened option for themselves or their children. Potential customers without dietary restrictions often get excited when they see we are selling puddings and popsicles, but they are turned off by the fact that our treats are vegan. This commonly leads to an unfinished sale. I suspect this is because the word “vegan” has a negative connotation to it when someone isn’t following a vegan diet. I know that I, too, would rather purchase a regular popsicle or pudding than a vegan one because I have a negative view of treats that are simply labeled “vegan.” Vegan means no milk or eggs, which means I’m usually not interested. There is a deeper meaning here to the label “vegan,” and I’d be interested to explore how this turns regular eaters off in future research.

My map of our corner of SOWA, which is not drawn to scale, shows all of the vendors who were set up near us on this Sunday. I struggled to find a way to represent the different segments of customers but decided on using a different color for each one. I used different types of lines to represent each person’s path in order to follow their steps so that I could draw conclusions on my observations. While it might look a bit messy, I tried my hardest to make it so that each footpath could be followed easily with your eyes or finger. This was not something I had considered before this project, but mapping overlapping footpaths so that they are all still visible is not an easy task. In the future, I would try this map again with overlapping layers so that each footpath would be visible on its own or together with the other paths.

My map of our corner of SOWA, which is not drawn to scale, shows all of the vendors who were set up near us on this Sunday. I struggled to find a way to represent the different segments of customers but decided on using a different color for each one. I used different types of lines to represent each person’s path in order to follow their steps so that I could draw conclusions on my observations. While it might look a bit messy, I tried my hardest to make it so that each footpath could be followed easily with your eyes or finger. This was not something I had considered before this project, but mapping overlapping footpaths so that they are all still visible is not an easy task. In the future, I would try this map again with overlapping layers so that each footpath would be visible on its own or together with the other paths.

This project took mere ethnographic observations and extended them to create a mapping of a food-centric space. Mapping out our section of SOWA allowed me to take another look at the assumptions I had made about certain customers and their patterns. It reiterated to me that food can create cultural and social identities, as well as unwritten rules and segmented groups. While we may not realize it, each and every decision we make in regards to food is a step towards shaping our roles and identities in society.