Afternoon Tea Seminar Series

Afternoon Tea seminars were a series of conversations on career and workforce development in which V.Scott Solberg, Ph.D, who is currently a professor in counseling psychology at Boston University, conducted casual interviews with distinguished researchers and faculty in the field of vocational psychology. Afternoon Tea seminars were organized by the Center on Education and Work at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Trian Tracy is a distinguished professor in counseling psychology at Arizona State University. He talked about a wide range of methods of career interest assessments.

Steven Brown, Ph.D. is a well-known faculty at Loyola University Chicago and a co-author of Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT). His talk focused on career decision-making difficulties as one of the major issues in career interventions and its solutions.

Mark Savickas, a professor at Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, is the author of Career Construction Theory and demonstrates a narrative method for helping clients in career counseling.

Ellen Henson is a senior employment service specialist in International labor Organization in Switzerland. She talked about global challenges especially career development needs of low- and middle-income countries.

John Vardallas is a founder and CEO of the American Bloomer sharing his perspectives about “All Things Bloomer.”

Dennis Winter is an expert and economic analyst modeling and forecasting and a vice-president and research of North Star Economics.

The conversation focused on learning what makes competitive and employable in today’s changing economy.

Graduate students who returned to college as an adult shared their experiences and resources they used to help them become successful and navigate challenges of going back to school.

Engaging in Remote STEAM and Career Readiness Activities

Our national webinar titled "Engaging in Remote STEAM and Career Readiness Activities" was held on October 23rd, 2020. Visit our YouTube channel to watch the full recording.

Building the Pipeline to Get Black, Hispanic Youth into STEM Careers

Our collaborative research with Sociedad Latina was featured on BU Today. Click here to read the full article.

Diversifying Exposure to Occupations in Elementary School

Diversifying Exposure to Occupations in Elementary School

by Cecilia Voetsch, Efe Shavers, Sara Langtry and Kimberly A.S. Howard

Have you ever heard of an ornithologist? Don't worry we hadn’t either. In school, many of us might have been introduced to a wide array of occupations such as doctors, lawyers, even engineers. But, there are so many more fields to explore; the possibilities are almost endless. In our work with elementary school counselors, we have found that they routinely introduce unique and interesting jobs to their students as a way of encouraging excitement about possible future occupations. They invite community members to describe their work, share what they like about what they do, and explain the path they took to get there.

In case you're still wondering, an ornithologist specializes in the study of birds, their behaviors, and their habitats. School counselors know that there is incredible benefit to exposing children to the range of careers present in their community, such as firefighting, small business ownership, and dentistry. Students begin to understand the world of work better when they get to meet and hear about the day to day activities of people in these jobs. At the same time, when children are given the opportunity to meet professionals in lesser known fields, such as ornithology, metrology (the study of measurement), or ichthyology (the study of fish), it encourages them to explore unfamiliar fields, and to become trailblazers into the unknown. Here are some of the ways you can make this happen.

- Present a Range of Careers: Think broadly about who to bring in. Diversify the occupations discussed beyond the familiar ones. If you live in a rural area, think about occupations to which your students might not already be exposed. If you live in an urban area, think beyond the occupations that students may see in their everyday environments. The goal is to expand the range of careers students know.

- Diversify Role Models. Think critically about the persons you are bringing in, particularly in relation to the occupation. Use what you know about occupational stereotyping to determine who you might invite to speak to your students. For example, in the sciences, perhaps bring in a female scientist instead of a male one; or perhaps invite a scientist of color, and/or a member of the LGBTQAI+ community. Expose the children to a wide range of models. When it comes to modeling, the most impactful models are those we can identify with on the most salient of characteristics such as race, gender, etc. The greater the diversity of role models presented, the less likely students are to think stereotypically about who can “do” certain jobs.

- Encourage Speakers to Show Depth: When students get to middle school and are exposed to the amount of work and time required to become a professional in a certain occupation, their interest can begin to wane. To combat this, invite speakers who talk about the ins and outs of the occupation, as well as the motivations that drove them to pursue that path. The speaker can also attest to how “non-academic” talents and skills helped them reach their goal(s)/current job. They can cite examples such as a love for people, the desire to help, preference to work alone, etc. This would expand on the “requirements” for occupations beyond completing high school and attending college.

- Keep it Developmentally Appropriate: Help your invited speaker explain, in developmentally appropriate ways, their journey to becoming qualified for the job they hold. For example, it would be confusing to a 2nd grader to hear a lawyer discussing the role of the LSAT, but the lawyer can explain the importance of going to college and on to law school, possibly touching on a simplistic explanation of what law school is. A quick preparation with the visitors should suffice to discuss these points. Another option is to consider developmentally appropriate play and hands-on activities that may parallel the basic skills of the chosen career. This is a great way to keep kids engaged and excited, and may even highlight important skill sets they naturally have.

By implementing career education practices such as these you encourage the next generation to explore a wide range of occupations. You ignite students’ natural curiosity and you help them to push the boundaries of what they think is possible.

Equality Can’t Wait: Financial Literacy Is the Key

by Betsy Kelder

Executive Director, Invest in Girls

Trust Your Gut, Trust the Data

It seems obvious that financial literacy enables young people and adults to make better-informed decisions in their lives than those who are not taught the basics of personal finance. Study after study proves that to be true, including the analysis of current literature by Tim Kaiser, Annamaria Lusardi, Lukas Menkhoff, and Carly Urban published by the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center (GFLEC) in April 2020: “The evidence shows that financial education programs have, on average, positive causal treatment effects on financial knowledge and downstream financial behaviors.”

Also worth noting, results from the 2018 National Financial Educators Council (NFEC) survey on financial acumen among Americans suggested that insufficient financial literacy cost households more than $295 billion that year. That’s a lot of dollars.

Though reluctant to use the overused phrase “now more than ever,” I will. Now more than ever, while the nation is coping with the effects of a global pandemic, there is also a financial crisis whose scope and impact is yet to be fully understood. For the unemployed and underemployed without a financial safety net, these are truly precarious times. As Carrie Schwab-Pomerantz, President of the Charles Schwab Foundation said, “The pandemic has underscored just how critical basic personal finance skills are in preparing for the unexpected. Financial literacy is a survival skill that everyone needs.” We talk of being able to save for a rainy day… Well, it’s pouring and many people have no umbrella.

The Solution Is Clear: Education and Early Intervention

Learn early and often. “Through financial literacy education, poor financial habits can be eradicated and displaced by more appropriate habits,” according to the nonprofit Financial Educators Council (FEC). And as economist and researcher Annamaria Lusardi recently wrote in Forbes, “Improving financial literacy must be part of the toolkit we use to move forward and be better prepared for the future, for shocks big and small, and to enhance economic opportunities for all.” Agreed!

Financial literacy is crucial to providing for one’s self (or family), planning for the future, and not being taken advantage of by players who would seek to capitalize on uneducated consumers.

The great opportunity we have to combat the troubling statistics that cause unnecessary hardship and adverse outcomes is to introduce concepts of personal finance to students before they make a decision about higher education or enter the world of work; before they apply for their first credit card or think about buying a car. Financial literacy can be thought of similarly to reading literacy—start early with the basics, get a clear understanding of how to sound out the words and put the sentences together, and then move to more advanced and complex books. Would you hand a 4-year-old War and Peace?

By learning about financial literacy while young, students can build good habits around spending and saving, and be better prepared to participate in and benefit from economic opportunities. When we shine a particular light on concepts like budgeting, credit, return on investment, and compound interest when students are in adolescence, we spark an interest and create a firm foundation at a critical time in creating good money habits.

The good news is that the vast majority of Americans believe that standard high school curricula should include financial literacy coursework, according to a 2020 poll by the National Financial Educators Council (NFEC).

But That’s Not All, Folks!

Financial literacy in young women has the potential to drive additional positive results for society, and Invest in Girls, a program of the Council for Economic Education (CEE), is focused keenly on this demographic. And for good reason.

IIG’s mission is twofold: to usher in the first generation of financially literate girls and to increase the number of women working in finance.

Whether living on their own or managing the finances for their family, working or planning for retirement, it’s particularly important for women to be equipped with the knowledge and prowess to make financial decisions that make sense for them. Research shows that investing in women is one of the most effective ways to impact society for the better. And also that a lack of financial confidence keeps women in bad jobs and life situations and precludes them from making some of the decisions that they want to.

In the finance sector, it’s true that progress has been made with regard to gender parity in the field of financial services at the entry-level, but breaking the ever-present glass ceiling, leaning themselves into the C-suite, and serving on boards remains wildly challenging for women.

Invest in Girls teaches tactical skills, builds confidence, and educates about various opportunities in the job market that high school girls can aspire to and apply to when they are ready to join the workforce. IIG offers age-appropriate curriculum and workshops that benefit young women in a number of ways.

Primarily, girls who participate in IIG programming are introduced to basic concepts, such as budgeting and personal finance, the stock market and other investment instruments, taxes, insurance, and philanthropic giving. These learnings will be valuable as they grow up and into their adult lives. In support of their consideration of options for higher education, students are taught about Financial Aid Forms, college loans, and college debt.

Another forward-looking aspect of financial education for girls in high school is centered on the potential for choosing careers in finance. By presenting girls with role models working in finance, connecting them to mentors, giving them exposure to companies and institutions by way of field trips, providing opportunities to network with professionals and peers, and sharpening their interviewing skills, IIG is encouraging young women to see themselves in private equity, financial services, banking, accounting, and portfolio management.

Not only does data prove that diverse teams lead to greater profits, why shouldn’t young women learn the tools of the trade and add their perspective, be it on Wall Street at an investment firm or on Main Street at the branch of a local bank, running a hedge fund or choosing which startups receive venture capital? (They should.)

Invest in Girls partners with independent, charter, and public schools, as well as nonprofit organizations, to provide financial education and opportunities to high school girls across the country. IIG’s outreach includes a focus on attracting students from diverse communities, where teaching financial literacy is a powerful tool for increasing representation in fields that have historically been white and male.

Investing in Girls

In less than 10 years, IIG has grown from 1 program to offering more than 35 successful programs, educating more than 5,000 girls. And we’ve already seen tangible growth since being brought under the aegis of the Council for Economic Education in 2019—a widely respected national organization that fosters the teaching of personal finance and economic education in our nation’s schools. Working with educators, families, and teens already in the CEE network allows for greater reach and scale when it comes to serving communities across the country.

We look forward to a time when it is safe to have after-school classes in person and on-site field trips again, but until that day comes, digital tools have enabled students outside of the northeast region, where IIG was founded, to raise their hands and opt in to the unique programming IIG offers.

The benefits of financial literacy are many. The first generation of financially literate girls will improve outcomes on the personal level, no doubt. Individuals with the knowledge and confidence necessary to run a household who can manage a family’s budget, teach their children the basics of money management, and contribute to society are the base of a stable economy. At the community level, more financially fit women will organically serve as positive role models as they support local tax bases and businesses.

At the institutional level, by increasing the number of women working in finance, we’ll see greater equality in how investment dollars are allocated, more profitable businesses run by diverse leadership and teams, and—we hope—the gender pay gap becoming a thing of the past.

One can dream that building gender equity in finance and a greater diversity of thought in conference rooms and breakrooms, will result in greater equality for the nation. I’m proud to say that Invest in Girls works toward this goal one classroom, one boardroom, and one click at a time.

Blast Off! Into STEM Career Pathways

About Authors: Yanling Dai and Yajing Chen are completing their Master’s Degree in School Counseling in the Department of Counseling Psychology and Applied Human Development at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education and Human Development. Yanling is interested in developing positive youth development programs, with an emphasis on developing a career identity. Yajing is interested in developing culturally responsive education programs, especially as it relates to higher education and career development.

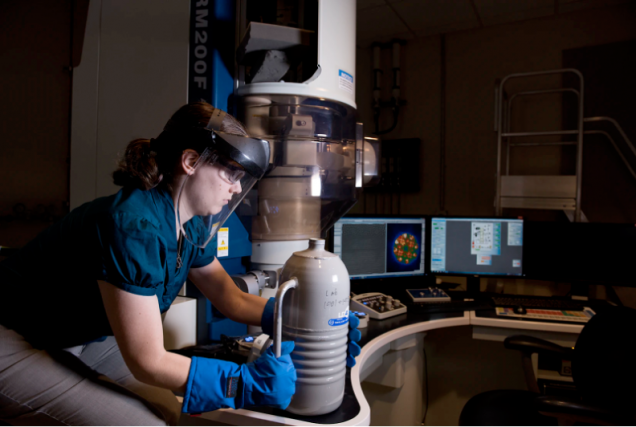

Steven is one of the many talented Latinx youth who begin middle school with an interest in science. He wants to explore more advanced science topics and was in search of STEM related opportunities in his school and neighborhoods. Latinx are severely underrepresented in STEM fields most of which are in high demand and offer high wages. According to the Pew Research Center (2018), Latinx adults represent 16% of the overall workforce but only 7% are participating in STEM occupations. Located in the heart of Boston, Sociedad Latina has been successfully working with Latinx youth and their families. Sociedad Latina offers afterschool and summer STEM enrichment programs that help students like Steven build STEM skills and enter STEM academic/career pathways. In collaboration with Boston University, Sociedad Latina incorporates advanced STEM learning opportunities using Network Science and helps them explore how the skills they are learning opens up a wide range of career opportunities.

“We want to make sure that our programs provide real opportunities. STEM programming really allows for Latino and English language learners to be able to participate in fun, engaging and interactive activities, and tie that to real world challenges they're facing in their community and at the same time, increase their knowledge and interest in STEM careers.” -- Alexandra Oliver Davila, Executive Director of Sociedad Latina

Sociedad Latina and Boston University are incorporating important evidence-based strategies to maximize youth engagement in STEM learning. These strategies include hands-on learning, summer bridge program, mentoring and creating safe, “counterspaces,” for youth collaboration.

1. Hands-on Learning

Supported by a growing number of studies (LaMotte, 2016; Yang et al., 2019 & et al), Hands-on Learning is an experiential learning strategy in which individuals are encouraged to participate in STEM learning through a variety of activities (National Science Foundation, 2019). The Network Science club at Sociedad Latina also helps the youth explore the scientific world through hands-on activities. Students learn about the networks around them (e.g. light bulbs and traffic) and develop new network systems using data available to them (e.g. ice bucket challenge and spread of disease/COVID-19). The Engineering and Technology club at Sociedad Latina is another example of hands-on learning. This summer, students received a STEM kit and were guided to make a Solar Panel Car. Steven expressed his excitement about this activity as it was his first hands-on experience using a science kit.

“I could learn about solar energy and work together with my amazing teachers and friends to make an amazing learning experience and have fun in this process.” -- Steven, 7th grade

For younger kids, it is important to keep in mind that the activities have to be fun and interactive. He also mentioned, “those fun activities are all the little things but put them together they become a big thing... you can make fun of a little bit and learn a lot at the same time.”

2. Summer Bridge Programs

Many studies suggest that summer bridge programs effectively enhance the diversity of STEM professionals (Ashley, Cooper, Cala, & Browness, 2017; Bruno et al., 2016; Wolfe & Riggs, 2017; & et al). The National Science Foundation (2019) also states that the summer bridge programs provide a more inclusive environment for underrepresented populations and open the door to STEM education and workforce development.

This year, Sociedad Latina offered a five-week Summer STEM Program that focuses on academic contents in the mornings and STEM activities in the afternoons. On Thursdays, the students participated in the Careers club, exploring their career goals and interests and skills aligned with their goals.

“Our goal is to build youth capacity to engage in STEM and help them become aware of how learning advanced STEM skills expands their occupational and life opportunities” -- Dr. Kimberly Howard, Principal Investigator, Boston University Wheelock College of Education & Human Development

3. Mentoring

Mentoring is a process where an individual is guided, advised, and modeled by experienced researchers and/or professionals. It establishes a long-term relationship with consistent instruction (National Science Foundation, 2019). Mentoring has been identified as a crucial element of building persistence among underrepresented minorities in the STEM field, as well as a successful strategy aimed at increasing their participation (Charleston, Charleston, & Jackson, 2014; Zaniewski & Reinholz, 2016).

The collaborative project between Sociedad Latina and Boston University provides the youth with an opportunity to build long-term relationships with faculty members from the Physics department as well as Wheelock College of Education and Human Development. Science labs at BU also get involved in this collaboration as guest speakers and by being role models for the youth. The project will also be providing access to industry professionals who will mentor teams of youth around specific projects.

4. Counterspaces/Safe Spaces

“The STEAM Summer Program helped me show my pride in science because I couldn’t ever show it as nobody else likes it with me.” -- Steven

Counterspace is a “safe space” for minority groups where they can learn in supportive environments that provide safe and inclusive experiences that promote belonging (National Science Foundation, 2019). As shown from Steven’s experience, programs like Sociedad Latina’s can create a safe and supportive learning environment for minority youth, where they can freely express themselves while cultivating their knowledge, interests and skills. The premise of the network science and career lessons is to let individuals see the world through the lens of how things connect to each other and to themselves. By building participants’ self-awareness and social awareness, the program empowers the students and further engages them to the STEM world. Due to Covid-19, remote learning was designed to be interactive in ways that allowed small teams of youth to work with an adult mentor on learning the Network Science concepts and exploring their emerging STEM talent and skills.

Steven’s experience is just an example of how one program can have a tremendous impact on youth in pursuing interests and careers in STEM fields.

“My love for science is just like a bomb. As soon as I was getting more into the program, it just blew up. I was starting to love science way more.” -- Steven

If more students from underrepresented groups can have access to STEM lessons combined with career development, we can expect to see more of them becoming interested in and pursuing STEM academic/career pathways.

“I really wish that more people could learn about the program because I would have assumed if it had more of the push to show it to the people what is like then it would be popular.” -- Steven

By Yanling Dai and Yajing Chen

SOURCES

Ashley, M., Cooper, K. M., Cala, J. M., & Brownell, S. E. (2017). Building better bridges into STEM: A synthesis of 25 years of literature on STEM summer bridge programs. CBE Life Sciences Education, 16(3), 1-18.

Bruno, B. C., Wren, J. L. K., Noa K., Wood-Charlson, E. M., Ayau, J., Soon, S. L., Needham, H., & Choy, C. A. (2016). Summer bridge program establishes nascent pipeline to expand and diversify Hawai‘i’s undergraduate geoscience enrollment. Oceanography, 29(2), 286–292.

Charleston, L. J., Charleston, S. A., & Jackson, J. F. L. (2014). Using culturally responsive practices to broaden participation in the educational pipeline: Addressing the unfinished business of brown in the field of computing sciences. The Journal of Negro Education, 83(3), 400-419.

LaMotte, E. M. D. (2016). Unique and diverse voices of African American women in engineering at predominately white institutions: Unpacking individual experiences and factors shaping degree completion (Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, MA). Retrieved fromhttp://scholarworks.umb.edu/doctoral_dissertations/278

NSF INCLUDES Coordination Hub. (2020). Broadening participation in STEM: Evidence-based strategies for improving equity and inclusion of individuals in underrepresented racial and ethnic groups (Research Brief No. 1). Retrieved from https://www.includesnetwork.org/viewdocument/coordination-hub-research-brief-im?

Wolfe, B. A., & Riggs, E. M. (2017). Macrosystem analysis of programs and strategies to increase underrepresented populations in the geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 65, 577-593.

Yang, D., Xu, D., Yeh, Jyh-haw, & Fan, Y. (2019). Undergraduate research experience in cybersecurity for underrepresented students and students with limited research opportunities. Journal of STEM Education, 19(5), 14-25.

Zaniewski, A. M., & Reinholz, D. (2016). Increasing STEM success: A near-peer mentoring program in the physical sciences. International Journal of STEM Education, 3(14), 1-12. More

International Trends and Innovation in Career Guidance

Angela Andrei, a member of the SEL IRN and also an exchange scholar in 2019, is one of the leading authors of this two-volume work by the European Training Foundation. The report discusses the mega trends in career guidance in the 21st century with country specific examples. To learn more about her work, click here for Volume I and here for Volume II.

Life and Work After Sports: Former NCAA Athletes’ Experiences of Athletic Retirement and Career Transition

This study examines former collegiate student athletes’ experiences of career development and transition out of sport and into post-college life and the world of work. For most student athletes, the termination of an athletic career is inevitable and coincides with graduation and transition into a non-sport career. Many student-athletes are unprepared for the transition and experience psychological and emotional difficulties that may interfere with mental health, wellbeing, and career development. This mixed-methods study explores recently graduated, former student athletes’ experiences of athletic retirement and career development.

National Study of Career Development Practice in the Elementary School

In order to better understand the challenges in providing career development programming to elementary school children, we are surveying elementary school counselors from across all 50 states. Specifically, we are examining practicing school counselors’ beliefs about, attitudes towards, preparation for, and practice of career development work with elementary school-aged students.

The current team members working on the national study are Yang Yu (Alex), Yian Xion (Rita), Bianca Barreto, Shilu Wang, Sophia Long, Lara MacIntyre, Amira Samra, Tahreem Nawaz, Shan Shan Yang, Nupur Aroskar, and Ritika Dinesh.

Elementary School Career Development: Exemplars of Practice

In recent years it has become increasingly understood that fostering positive career development in the elementary school years provides a foundation for the college and career readiness endeavors at the high school level. Despite this recognition, there continues to be hesitation to engage in career-related programming in the elementary school years. In this comparative case study, we have identified elementary school counselors who are considered by their peers, colleagues, and supervisors as being “exemplar career educators.” We are studying their practice so as to identify both the school counselor-specific factors, as well as the context-specific conditions that are associated with the provision of exemplary career development programming to elementary school-aged students.

Engineering Teaching Efficacy

Science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education has become a priority in many school districts, which makes it critical that teachers feel well-prepared and confident teaching these subjects. This is especially true in secondary schools when students are making decisions about their educational and vocational futures with long-term ramifications.

The Engineering Teaching Efficacy Scale (ETES) was designed to measure middle school teachers’ confidence in teaching STEM subjects. The 25-question ETES was adapted from the Science Teaching Efficacy and Beliefs Instrument to apply to engineering rather than science teaching. Preliminary research has suggested the ETES has strong psychometric properties and reliability.

The current investigation builds upon this early study by recruiting a larger, nationwide sample of STEM teachers to pilot an initial version of the ETES. These data will be used to investigate the factor structure, psychometric properties, and reliability of the ETES in this expanded dataset.