Click on cover to read our writeup:

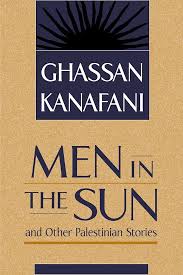

Ghassan Kanafani, Men in the Sun

Men in the Sun is a 1962 novella by Ghassan Kanafani.

Men in the Sun is a 1962 novella by Ghassan Kanafani.

The story follows three Palestinian refugees of different generations seeking to migrate to Kuwait for work. Kanafani’s didactic writings are praised for articulating Palestinian conditions of displacement and inspiring national fervor amongst Palestinians.

Men in the Sun centers characters who have been pushed to the margins of their community and who express discontentment with the national cause. Kanafani offers a vividly tragic and honest depiction of the costs of national struggle with the character of the three men’s driver, Abu Khaizuran. The reader is introduced to Abu Khaizuran’s character when Marwan, the youngest of the three Palestinians migrating to Kuwait, is thrown out of the smuggler’s shop. Talking to Marwan, Abul Khaizuran presents as sharp, and he’s even able to guess Marwan’s family situation, remarking matter-of-factly, “One doesn’t have to be a genius to understand. Everyone stops sending money to their families when they get married or fall in love”(42).

Even though Abu Khaizuran is aware of the cliches of family life, he is the only character exempt from family responsibility, since he has never married. Assad, who seeks freedom from married life, remarks “I was thinking you had a splendid life. No one to drag you in any direction. You can fly off alone wherever you like..” In the original Arabic he repeats “تطير..تطير…تطير” or “fly…fly…fly.” Yet Abul Khaizuran does not live a bachelor’s paradise, as Assad fantasizes; he is restricted from settling down since he has “lost his manhood” ten years prior as a freedom fighter in the 1948 war.

The memory of his surgical castration is revealed through Kanafani’s signature temporal shifts, as Abul Khaizuran flashes back to that foul scene under the hospital light. He is disillusioned by the national cause and rejects any nationalist fervor since he’s lost enough. “He had lost his manhood and his country, and damn everything in this bloody world.” Loss and victimhood – ضاح are repeated throughout Abul Khaizuran’s internal monologues. –Moriah Mikhail ’22

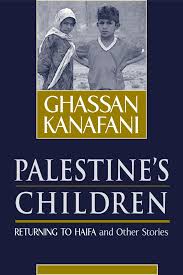

Ghassan Kanafani, Returning to Haifa

Returning to Haifa is a 1969 Palestinian short novel by Ghassan Kanafani, translated into English by Karen E. Riley.

It was the basis of one of the first Palestinian film, made in Lebanon by Kasem Hawal in 1982, and it was later adapted into a play by Ismail Khalidi. The book is about Said and Safiyya’s journey to the house in Haifa from which they were expelled during the 1948 Nakba. When they were forced to leave, they accidentally left behind their baby Khaldun, who was later adopted by Jewish immigrants and renamed “Dov.” After the 1967 Six-Day War, Said and Safiyya are finally allowed to visit their old house in Haifa for the first time, meeting the settlers and Dov, whom they only later discover to be their son. The families’ encounter forces them to confront the painful memories and what it means to “belong” to a specific identity. The story questions the gain/loss of identities and memories throughout displacement.

If you are interested in Kanafani’s shorter writing, you can also start with his short story collection Palestine’s Children. -Ruofei Shang ’25

Sahar Khalifeh, Passage to the Plaza

Passage to the Plaza is a 1990 novel by Sahar Khalifeh, translated into English in 2020.

The novel is dominated by three female characters from different social backgrounds, who navigate the complexities of the intifada as they are forced to take refuge in a disreputable home during a curfew. Khalifeh has used this fictional story to offer class and gender perspectives on Palestinian narratives of occupation.

Nuzha, in Passage to the Plaza, is no stranger to loss. Similar to Abu Khaizuran in Ghassan Kanafani’s famous novella Men in the Sun, the national cause has been the culprit. Nuzha’s story is set against a different background, as hers takes place in the Bab al-Saha quarter of Nablus during the 1987 (first) intifada. Disgraced by her mother’s reputation as a suspected traitor and her own position as a prostitute (though it’s unclear which is more scandalous), Nuzha is ostracized from the community. The three other main characters hesitantly find refuge in her infamous home once the imposed curfew restricts them. As Samar questions Nuzha for research, she is shocked by her lack of patriotism, telling more than asking her “And you love Palestine.”

Nuzha has lost everything of value to the intifada. Her mother was killed for being a suspected traitor, her brother’s whereabouts are unknown since joining the resistance, and her ex-lover pimped her out to buy weapons from Israeli officers. She is excluded from community and a role in nation-building as a prostitute and a deadbeat mother. As Joane Nagel writes in the Handbook on Men and Masculinities: “Women are mothers of the nation, so purity must be impeccable, and so nationalists often have a special interest in the sexuality and sexual behavior of their women. Women’s shame is a nation’s shame.” Nuzha is without community and lacks the security of a family. In this way, she floats in a suspended space.

Nuzha refers to Palestine irreverently as الغولة , which translates to “ogre” or “cannibal,” using the feminine form of the noun to allude to the feminized romanticization of Palestine. Khalifeh turns the typical symbol of a feminine homeland on its head to present the image of a female cannibal or (what some might even refer to Nuzha as) a “man-eater” or “she-devil.” She also wholly rejects the practice of ululating in celebration of her brother’s martyrdom, spitting out in anger “Shit on Palestine! I want my brother, not Palestine.” She resists the female role in conflict to serve as a symbol and spectator/supporter of male bravery and prowess. As someone who has lost her family to the intifada, she finds it ridiculous to participate in the celebration of martyrdom. –Moriah Mikhail ’22

Emad Burnet, Five Broken Cameras

Emad Burnat’s Five Broken Cameras is a multi-award-winning documentary.

It showcases the birth of the Palestinian resistance in the city of Bil’in between 2005 and 2010. Emad, a villager and father who initially bought his first camera to film his fourth son’s childhood, ends up using the same camera to film Israeli workers when they occupy his beloved village of Bil’in. In the beginning of 2005, the Israeli government builds a fence dividing the village and a nearby illegal Israeli settlement being constructed, in a greater attempt of colonizing the West Bank. Throughout the film, Emad documents Israeli workers uprooting olive trees, building separating walls in the middle of his village, protests against the occupation (turned violent by the IDF), and the construction of illegal settlements on his land. Emad doesn’t consciously choose to become a journalist, much less a filmmaker, but he explains that “when something happens in the village, my instinct is to film it”. Five Broken Cameras is thus a collection of instincts creating this magnificent film.

Documenting the occupation in the West Bank is an extremely dangerous action, criminalized by the Israeli government. Emad risks his life documenting the resistance in Bil’in, and as a result, the Israeli government breaks a total of five of his cameras, hence the name Five Broken Cameras.

While the cameras collect hundreds of hours of footage, what makes the movie so compelling is the composition of what is collected. Burnat splices together many high intensity scenes back to back to give a sense of what it’s like to live in a warzone to the viewer, but his most potent shots come from the juxtaposition of loud, abrasive scenes to those of complete silence. This pace is set early on in the film at around the seven and a half minute mark. Here, gunshots and explosions are heard throughout the village as IDF soldiers push in, attempting to scare off the Palestinians and force them to retreat home. In a unifying scene we see the people of Bil’in march through the streets with instruments in hand, chanting and smiling to show their resilience. The constant sounds of war have not dampened their spirits, they will continue to fight and move forward as they have always done. This shot gives the viewer a sense of hope, it would lead perfectly to a following scene of the town uniting for a celebration, or maybe just a moment of peace. But instead we’re met with total silence as a fire rages in the background. These contradictory shots are used throughout the film to snap the viewer back to reality. As good as things may seem in the moment, as high as spirits get, they always crash down in an instant when reality hits.

Five Broken Cameras is not about Palestinian suffering but about life, showcasing what suffering can create. The film demonstrates deep Palestinian resilience and a strong connection to the land. The film documents the greater battle against the Israeli occupation on the Palestinian people, a perspective that is not often portrayed in the media. Emad shows the creation of settlements, settler violence, annexation of land, dedication and loyalty to the land, criminalization of the press, and robbery of Palestinian childhood, justice, and life. Emad discusses the connection between the camera and the battlefield. “When I film, I feel like the camera protects me, but it’s all an illusion,” he narrates as he films his brother’s arrest, emphasizing the dynamic between the gun and the camera which is analyzed in detail in David LaRocca’s, The Philosophy of War Films.

Showing burned olive trees amidst a dabke celebration, Emad is able to encapsulate the Palestinian dilemma among occupation in two consecutive scenes. Through Emad’s raw filming style, the viewer truly gets to experience what it’s like to resist the Israeli occupation and what Palestinians in the West Bank have to go through on a day-to-day basis, which is still relevant in 2024. Five Broken Cameras allows us to understand Palestinian resistance in all its forms.

As Emad Burnat sums up: “Healing is a challenge in life. It’s a victim’s sole obligation. By healing you resist oppression. But when I’m hurt over and over again, I forget the wounds that rule my life. Forgotten wounds can’t be healed, so I film to heal it. But I’ll just keep filming it helps me confront it to survive”- Noora Lahoud ’25 & Griffin L’Italien

Amer Shomali and Paul Cowan, The Wanted 18 (film)

The Wanted 18, released in 2014, is an animated documentary about a true story that takes place during the second intifada in the Palestinian village of Beit Sahour.

The Wanted 18, released in 2014, is an animated documentary about a true story that takes place during the second intifada in the Palestinian village of Beit Sahour.

The film portrays the story of Palestinians in the village who bought 18 cows and attempted to start a dairy farm to provide their own milk, make money, and boycott Israeli products. The film is a funny, witty story of Palestinians in the village trying to save the 18 cows from getting confiscated by the IDF, which has claimed they are a threat to Israel’s security. The Wanted 18 displays the diverse ways in which Palestinians are forced to resist occupation, highlighting the famous steadfastness of Palestinians while also demonstrating the brutal conditions endured during the second intifada. The humorous animation style makes The Wanted 18 stand out from other films about Palestine. -Noora Lahoud ’25

Leila Abdelrazaq, Baddawi

Baddawi is a graphic novel by Leila Abdelrazaq that recounts her father Ahmed’s childhood to adolescence in the Palestinian refugee camp, Baddawi.

Ahmed’s story unfolds amidst the Lebanese civil war as he navigates boyhood, conflict, acceptance, loss, and identity. Leila Abdelrazaq is a young Palestinian-American author and artist who explores themes of diaspora, refugeehood, history, and borders in her work.

From the opening panel of Baddawi, Leila Abdelrazaq presents her interpretation of Palestine as abstract and imagined. The leading caption reads, “Palestine is buried deep in the creases of my grandmother’s palms.” Lining the panel borders throughout the graphic novel is the traditional Palestinian embroidery, tatreez. The patterns are intended to showcase preservation of Palestinian identity, yet Leila shares that this widely popularized symbol is not native to her family’s ancestral village in Palestine. The practice of embroidery was actually taught in refugee camps like Baddawi as an attempt to resist cultural erasure and became a symbol of Palestinian identity through its practice in the camps. This process is authentic to the Palestinian diaspora, demonstrating how culture and identity persist outside of national borders. Abdelrazaq notes, “It’s a process of nation-building in the sense of coming together and deciding tatreez represents us all.”

Throughout Baddawi, Leila Abdelrazaq grants the reader flashes of Palestine persisting. A series of panels shows Ahmed gathering thyme for za’atar, a staple in Palestinian households, and preparing the aromatic mixture. Against a pastoral landscape, a caption reads, “Recipes are passed on in families, and vary region to region.” In the following panels, Ahmed’s mother passes the recipe to Ahmed (and the reader), describing the process step by step. His mother tells him “You know Ahmed, the next time you gather thyme for za’atar it will be in Palestine,” and in the following panel, lined with tatreez, Ahmed visualizes what Palestine might look like. The next page cuts to the 1967 defeat of the Arab armies against Israel. Although Ahmed’s mother cannot fulfill the promise of return, she passes on a tradition that prompts him to imagine Palestine, somewhere he’s never been.

Baddawi rarely fixates on issues of the national cause or fascinations of statehood. Abdelrazaq preserves Palestine as abstract, something that can be drawn onto the page. This practices keeps with the tradition of transmitting Palestinian culture as an act of resistance. In this way, tatreez and za’atar are not trivial incidentals of culture. They are intentional preservations that help maintain identity across a scattered diaspora. Leila Abdelrazaq reflects: “All of these symbols and imaginaries help build a nation. The way I like to think about it is that we exist and have always existed beyond the nation-state.” –Moriah Mikhail ’22

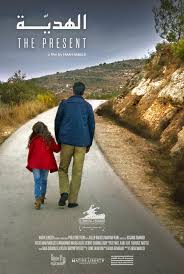

Farah Nabulsi, The Present

The Present is a a 2020 short film directed by Farah Nabulsi that explores the daily struggles faced by Palestinians living under illegal Israeli occupation.

The Present is a a 2020 short film directed by Farah Nabulsi that explores the daily struggles faced by Palestinians living under illegal Israeli occupation.

The film follows a small family, Yousef, his wife, and their daughter Yasmine. Since it is Yousef and his wife’s anniversary, he takes his daughter to travel to buy a gift for his wife. In the short 24 minutes, the film showcases the physical and emotional difficulty for Palestinians to perform such an ordinary task. Their plans get delayed and they are humiliated at arbitrary military checkpoints. What seems to be a mundane activity for the viewer, normally taking no less than a few hours to complete, turns out to be a day-long, physically demanding, and emotionally traumatizing ordeal for Yousef and Yasmine. It is an honest and direct portrayal of the harsh reality living under the occupation. -Ruofei Shang ’25

Adania Shibli, Minor Detail

Minor Detail is a 2017 novel by Adania Shibli that revolves around “the incident” in which a young Bedouin girl is raped and murdered by Israeli soldiers in the Negev on August 13, 1949.

The novel is split in two sections, the first following the perpetrator leading up to the incident and the latter narrated by a young woman from Ramallah obsessively investigating the details of “the incident” 50 years later. Shibli emphasizes that she does not write about Palestine but within Palestine, as what she calls “a position of witnessing.”

Unlike some scholars such as sociologist Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Adania Shibli decenters the colonial context to present the incident as senseless violence that one should resist rationalizing. Shibli presents the scene of the incident as a banal crime. Nearing the day August 13, 1949, the officer’s actions become increasingly erratic after suffering a festering spider bite. There is not much internal monologue to explain the officer’s thought process in the moment of the incident. It’s almost as if he does it just because he can. Of course, Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s analysis holds here. The officer is shielded by Israeli policies that strip Bedouin children of security and make them victims of gendered settler-colonial violence. The real-life platoon officer, who remains unnamed in Minor Detail, wrote in his report of the incident, “I took the Arab female captive. On the first night the soldiers abused her and the next day I saw fit to remove her from the world.”

Although Shibli does not share his name (Moshe) or other details such as this report in the novel, her telling of the crime preserves its senselessness. “I saw fit to remove her from the world” captures the banality of the crime but reminds us that for an Israeli officer with orders to ethnically cleanse the Negev of remaining Arabs, this precisely fits his job description. The female narrator has internalized and accepted conditions under Israeli domination so that these incidents are mundane, banal and almost expected. This acceptance of violence is what Shibli (as she says in this interview) pushes against. –Moriah Mikhail ’22

Darin J. Sallam, Farha

Farha is a 2021 film directed by Darin J. Sallam, showcasing one story from the 1948 Palestinian Nakba.

The story is centered around Farha, a 14-year-old Palestinian girl who is the daughter of the leader of the village. She was ready to pursue an education in the city, having convinced her father. However, her dreams are abruptly shattered when her village comes under attack by Israeli soldiers. As violence escalates, her father hides her in a small storage room and attempts to protect the village. While being isolated, Farha witnesses horrific events through a small opening in the door, including the brutalization, killing, and the destruction of her village.

Farha beautifully bridges personal storytelling with broader historical and political context of war and displacement in the Arab world. Filmed from Farha’s perspective, it offers a deeply emotional and unique way to engage with the lived experience of those caught in the chaos of war. The scene of Farha and Fareeda dreaming of their future, only to have their childhood shattered by violence, captures the abrupt loss of innocence that defines many narratives of war. Moreover, the film’s depiction of events reflects real-life atrocities that have unfolded over decades of genocide, ethnic cleansing, and occupation. This parallel between fiction and ongoing reality is a critical reflection on how Arab cinema bears witness to historical and contemporary struggles. – Ruofei Shang and Chaimaa Chkounda

Carol Mansour, Aida Returns

Aida Returns is a 2023 documentary film directed by Carol Mansour. The film follows the director’s mother, Aida Mansour, in her last days battling Alzheimer’s.

Aida Returns compiles footage from right before her passing, an older interview, photos of her childhood in Palestine and her life in Beirut and then Montreal, and present day footage of Mansour’s efforts to get her mother’s ashes back to Yafa. This documentary is unlike any genre of film I have seen before. It is a personal, intimate story, not focused particularly on the military histories of war, but instead on one woman’s life and the posthumous journey that she is brought on. There are windows into historical moments one might have learned about in a history class, but through the lens of one woman’s experiences.

One of the brightest lights of this film is the care that Carol’s friends Raeda, Tanya, and Angelique bring to the task, as they embark on this meaningful journey on behalf of their dear friend. Ultimately, the film is a profound example of how Israel discriminates and oppresses Palestinians in both life and death, but how despite this, the resilience of the Palestinian people and their steadfast memory persists. A taxi driver in Yafa put it best: “even if they die in a foreign land, the homeland and the earth of the homeland will embrace him,” almost as if the land was waiting for Aida to return. – Jasmine Lee

Hany Abu Assad, Paradise Now

Paradise Now is a provocative thriller crime film directed by Hany Abu-Assad. The film provides a layered themes to be explored, which include loyalty, sacrifice, and the overwhelming influence of accounts forged by decades of occupation.

By centering the film around two young individuals often undermined in a wider discourse, the film uncovers the personal struggles, psychological anguish, and the ethical dilemmas that underpin their choices.

The film follows childhood friends Said and Khaled as they are recruited for a suicide bomb mission in Tel Aviv. It also follows Azzam, the love interest of Said and the director of a humanitarian organization. Khaled and Said follow a virtuous perspective on the occupation, agreeing to commit a terrorist attack in the name of ending the occupation. Azzam differs. She argues that returning the violence to Israel only gives them an alibi to continue their encroachment on Palestine. Khaled and Azzam get into an argument about this in the film’s third act, where Khaled argues that it doesn’t matter: whether they fight back or not, Israel will continue its violence.

As Khalid and Said begin their mission they are faced with a tangled emotional surge of anger, despair, and hope. Said is a character deeply motivated by the loss of a loved one that occurred due to the occupation and therefore, views this mission as a way to reclaim his dignity and find a sense of purpose in a life that has been impaired by poverty and humiliation. In contrast, Khaled’s determination slowly fades as he wrestles with feelings of doubt and fear about the consequences to come. In both cases, tensions arise as Khaled and Said juggle both their shared sense of duty as well as their own individual fears and ambivalence. The portrayal of humanity towards two men on the verge of a life-altering choice makes Paradise Now captivating as well as a meaningful contribution to a conversation on war and identity in the Middle East. – Sophie Haddadeen and Mickie McCool

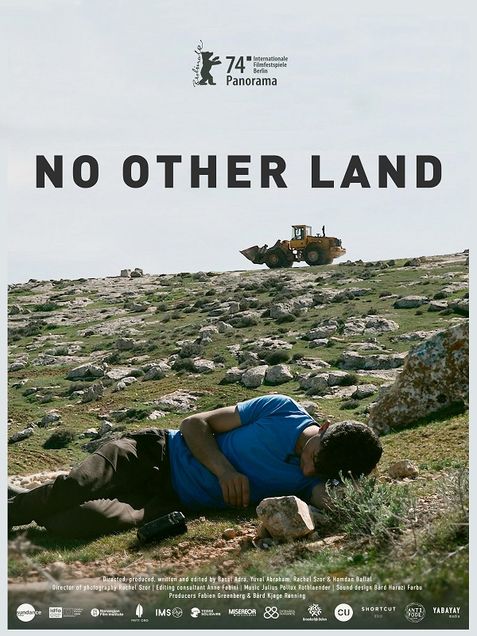

No Other Land

Directed by Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham, and Rachel Szor

No Other Land tells the story of life under occupation in Masafer Yatta, a Palestinian village in the West Bank whose people have been subjected to Israeli military control and displacement for generations.

Directed by a team of Palestinian and Israeli journalists, this cross-cultural collaboration follows Adra’s family and neighbors in their continued struggle against expulsion, as the IDF works to construct a military training facility on their land. The story is powerfully moving and executed with a flawless visual aesthetic that seamlessly transitions from beautiful shots of rocky landscapes, to dimly lit conversations so astute that they could be scripted, to shaky handheld protest footage shot vertically on an iPhone.

We watch as Israeli bulldozers demolish Palestinian homes and schools without warning, literally ignoring their cries and violently suppressing their objections. We see this community’s steadfastness as they gather their belongings and set them back up to make new homes in the land’s caves, providing a stunning visual representation of belonging—paired in almost perfect contrast with the image of IDF soldiers riding away when they’re done. This very conflict is then reflected directly in the onscreen conversations between Adra and Abraham, whose private moments seem to be overshadowed by an undeniable tension: resistance is survival for one and politics for the other—leaving is an option for one and impossible for the other. Regardless, the closeness that develops in their relationship becomes an essential component of the film as they maneuver the complexities of solidarity and dissent on an interpersonal level. – Mara Farrell

Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine

The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine documents several radical developments within Middle Eastern politics.

The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine documents several radical developments within Middle Eastern politics.

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the outset of World War I, the League of Nations granted control of Palestine to the British empire. In accordance with the Balfour Declaration, British-mandate Palestine was unilaterally recognized as a national homeland for the Jewish people despite the country’s overwhelming Arab-Muslim majority. When the British Empire withdrew in 1948, Zionist paramilitary forces depopulated thousands of Arab villages throughout Palestine, seizing nearly 80% of the land in the process. The state of Israel was founded on May 14th of the same year.

Arab perspectives are often erased from academic coverage of the Israel-Palestine crisis. Khalidi, on the other hand, analyzes the complex process of colonization and subjugation through the lens of the ongoing Palestinian struggle. The war on Palestine, spanning Ottoman, British, and eventually American hegemony, demonstrates the absolute devastation and injustice inherent to imperialism. The undying spirit of liberation highlighted in this book is shared by all living under the yoke of systemic oppression. – Joshua Emokpae

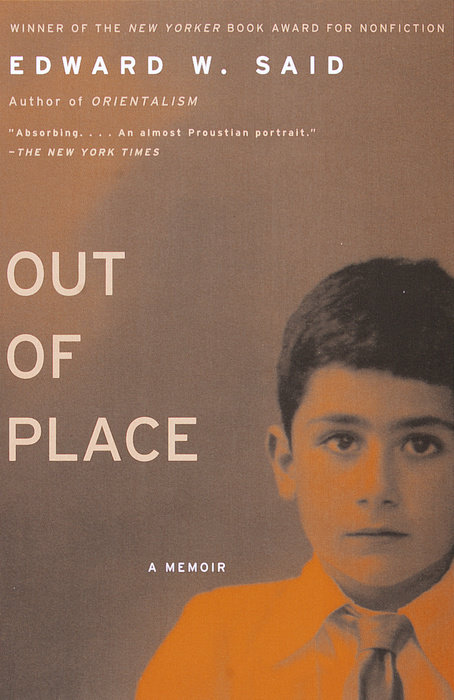

Edward Said is widely recognized as the first Palestinian voice to engage Western audiences in the question of Palestine.

Edward Said is widely recognized as the first Palestinian voice to engage Western audiences in the question of Palestine.

His book, Orientalism, became a seminal text in the field of postcolonial studies after its release in 1978. Pursuing bachelor’s and doctorate degrees in English and literary studies steeped him in Western narratives and paradigms, allowing him to scrutinize and criticize them in his theoretical, political, and historical works.

If you’re looking for behind-the-scenes insight into Said’s career, this memoir won’t provide one. Said omits his academic and political theories and works almost entirely and instead takes us chronologically from his early childhood through the divorce of his first wife. As the title suggests, Out of Place reflects on the core theme of his life–a nagging disharmony, outward and inward–which set in during his childhood between Egypt, Lebanon, and the American Northeast. Reading it, I got the sense that he left no inner stone unturned. His rigorous interior exploration accounts for the physical, emotional, and psychological components of his displacement and traces their origins and repercussions. Physical displacements destabilized his sense of identity, cleaving a rupture between outer and inner selves that he would spend his life trying to understand and repair. Spurred by his cancer diagnosis, the tone is often urgent and the narrative remains pregnant with a sense of impending mortality. – Leila Elayan ’26

Mourid Barghouti, I Saw Ramallah

Barghouti recounts his return to Palestine after a 30-year-long exile in I Saw Ramallah, which opens with him crossing the bridge between Amman and Ramallah and ends with the sleepless eve of his exile’s resumption.

He finds that returning does little to ease the psychological unrootedness caused by his initial exile from Palestine in 1967, when his final exams at the University of Cairo were interrupted by the news that the Israeli military occupation of Palestine’s West Bank had made his return home impossible. Exiled again from Egypt in 1977, he continued to accrue exiles and found himself unable to connect with whatever land he stood on, including the Palestinian land to which he returned. His return narrative describes a “wasteland” stripped of the rosiness of memories and the passion of nationalist propaganda. This disillusionment complicates rhetoric that celebrates return’s antidotal properties and the essential significance of the Holy Land. His body features centrally on each page, enabling Palestine to fall from abstract to literal when the land is beneath his feet and between his fingers. – Leila Elayan ’26

Ghada Karmi, In Search of Fatima

In Ghada Karmi’s first memoir, In Search of Fatima, she reflects on her adolescence in London’s Palestinian diaspora and her rise to political consciousness.

Ghada Karmi is an influential activist for and scholar of the Palestinian cause and political-national situation. Her family’s exile from Palestine in 1948 and her individual return trips in 1998 and 2000 bookend this chronological, first-person narrative which details her childhood through early adulthood. Karmi recalls how she had eagerly assimilated into British culture after her family relocated to London, but evidence of her Otherness and racialization gradually corroded the self that she had conceived of as white and utterly British. Her self-analysis interrogates a deeply-entrenched desire to be accepted by her white, Western communities that, alongside her internalized racism and sexism, obstructed her political and Palestinian consciousness. – Leila Elayan ’26

Sarah Aziza, The Hollow Half: A Memoir of Bodies and Borders

Aziza’s first book testifies to the versatility of the life and self-writing genre, combining aspects of memoir, diary, essay, and poetry.

A constant stream of end and footnote references to literary prose and verse, critical non-fiction, prominent activists and political figures, and historical facts enriches Aziza’s prose and creates a unique reading experience. Her father hails from Deir al-Balah and ‘Ibdis in Gaza, but he and his family were exiled to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where Sarah spent some of her childhood before moving to the Chicago area.

Aziza’s anorexia and subsequent path to recovery anchors the narrative’s timeline. Histories of her father and grandmother and their exiles splice her own memories and anecdotes. The body and the land are beyond mere entanglement in Aziza’s memoir–she demonstrates how they both became one perpetrator of and terrain through which she experiences exile. – Leila Elayan ’26

Hala Alyan, I’ll Tell You When I’m Home

A self-proclaimed, English-speaking Scheherezade, Alyan illuminates infertility, surrogacy, addiction, generational displacements, and the capacity of storytelling to enslave and liberate under the frame story of her surrogate’s pregnancy.

Political circumstances have flung her far and wide, from Illinois, Kuwait City, Beirut, Oklahoma, Maine, to New York City. She shows how the places in which she has lived insist on living in her, alongside the exiles she has endured and inherited, too. Alyan’s memoir, following two novels and five collections of poetry, straddles prose and verse. With storylines and stray thoughts splicing one another, her narrative captures the dynamism of memory and its reciprocity with the march of the present.

Randa Jarrar, Love is an Ex-Country: A Memoir (Expanded Edition)

Randa Jarrar takes a cross-country road trip in Love Is an Ex-Country, seeking to commune with a country toiling to shrink and police her queer, Muslim, fat, and femme voice, body, and sexuality.

She addresses her contentious relationship with America as an Arab-American whose experiences fall variously between privilege and oppression. Born to an Egyptian mother and Palestinian father in Chicago, she spent her childhood in the Arab world before the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait City prompted her family’s immigration to Connecticut.

Taking a tone somewhere between essay and blog post, each chapter collects bits of memories, facts, opinions, and associations to address a theme. At its core, this memoir seems to be a reflection on the origins of her voice and the insatiable drive to use it. Jarrar’s memoir is evocative for how she foregrounds sexual pleasure and kinks, but its true eroticism comes from her sensually lived and recorded experiences. The expanded edition includes a resonant essay on maternality and the Virgin Mary, plus an additional introduction and afterward that reflect on the gifts that self and life writing have given her. – Leila Elayan ’26