Babies may have a more complex perception of their environment than previously understood, picking up on visual and audible cues to make judgements about the people around them. Babies are also making decisions about their own actions. For example, babies who bounced rhythmically and in sync to music with a dance partner were highly likely to help that partner with small tasks, like picking up an object out of reach.

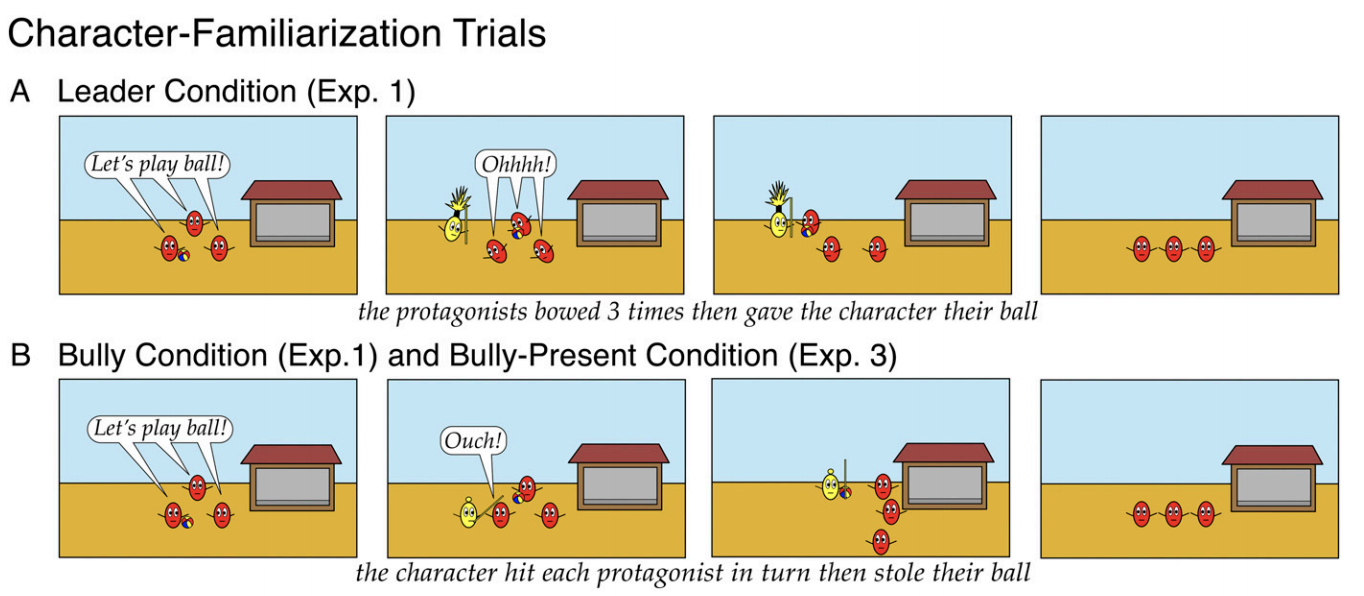

Results from a recent study indicate 21-month-old infants may be able to differentiate a bully from a leader. Francesco Margoni and colleagues assessed babies’ reactions to different scenarios involving two types of authority figure: either a respected or feared character. The respected character represented a leader, and the feared character represented a bully.

All of the infants first watched two scenes involving characters playing ball before an authority figure arrives. These scenes were used to familiarize the babies with the two types of authority. In one scene, the characters bow to a leader and hand over the ball, which the leader takes and leaves. The second scene featured the characters being hit by a bully and having their ball stolen by that bully.

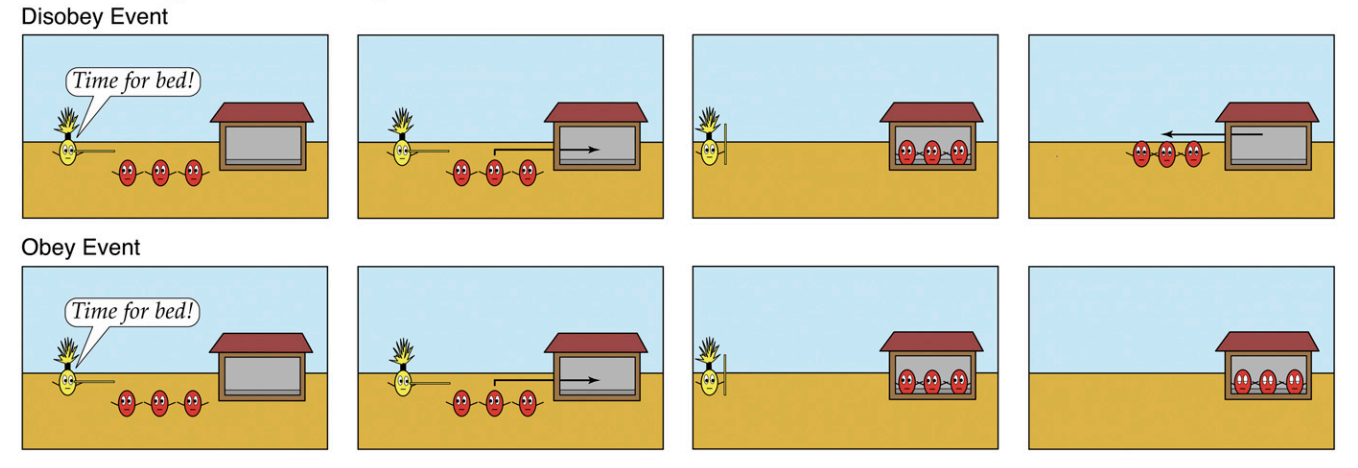

Babies were then randomly assigned to two different groups, and watched test scenes in which the authority figures return. For one group, that authority figure was the leader; for the other group, the authority figure was the bully. At the beginning of these test scenes, the authority figure first commands the characters to go to bed and they obey. The authority figure leaves. Then, the babies watch two further scenarios: in one, the characters continue to obey the command to stay in bed, and in the second, the characters disobey the command and leave bed.

Given that the researchers could not ask the infants to verbally express which character they think is the bully and which is the leader, they watched the babies’ eyes. They measured how long the infants observed the obey and disobey scenarios.

Infants who watched the leader looked at the disobey scene longer than the obey scene. The researchers took this to mean the babies expected the characters to stay in bed, even after the leader left. Since the disobey scene did not match their expectations, the babies looked at it for longer than the obey scene.

The babies who watched the bully stared at obey and disobey scenes for similar amounts of time, indicating they may have considered both outcomes plausible. The babies watched the characters stay in bed, presumably out of fear of the bully returning. They watched equally as long when characters disobeyed the command, and the absent bully no longer had power over them.

According to the researchers, these results provide a basis to further explore the way infants recognize power structures in their environment. Prior research has found that babies may expect smaller characters to give into larger ones in situations of conflict, but not much was known about babies identifying different types of power. Margoni and colleagues suggest combining their findings with this previous research, to observe whether the relative sizes of authority figures influence the way infants distinguish leaders from bullies.

Feature image: Nattanon Kanchak/iStock

Images in article:”Infants distinguish between leaders and bullies, Francesco Margoni, Renée Baillargeon, and Luca Surian, PNAS September 18, 2018 115 (38) E8835-E8843; published ahead of print September 4, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1801677115. Fig. 1. (detail) Schematic depiction of the character-familiarization trials in the different conditions (A–E) of experiments 1 to 3. Fig. 2. (detail) Schematic depiction of the order-familiarization and test trials in the leader condition of experiment 1. Trials in other conditions were identical, with two exceptions. First, in each condition, the character was that shown in the character-familiarization trials for that condition (Fig. 1). Second, in the bully-present condition, the character remained in the scene after giving her order.