The Marvelous Misunderstanding of Miss Mustard Oil

Today's post, the second in our series from student's in MET ML 619, The Science of Food and Cooking, with Professor Valerie Ryan, is submitted by gastronomy student Julian Plovnik.

Last January, I accepted a job with a company whose focus centered around the delivery of authentic, homemade food to hungry customers across the country, with dishes being made predominantly by immigrant populations living in major U.S. cities. I was fortunate enough to be in a role that facilitated a lot of 1-on-1 interaction with the cooks on our platform, allowing me the opportunity to ask them questions about their backgrounds, national cuisines, and specific culinary traditions. Conversations often included winding trips down memory lane, emotional stories about each cook’s journey to the U.S., and obviously lots of talk about food. It was not out of the ordinary for me to learn something new each day. In fact, it was rare for me not to. From ingredients like jaggery, galangal, and kaffir lime, I was constantly being introduced to food and foodways that lived outside of my daily life experiences.

For the most part, I was never surprised by anything I learned. There was no reason for me to question specific techniques or dishes that some of the cooks on the platform wanted to prepare. That is, until I was asked by one woman what seemed to be a very simple question at the time. “I’m not allowed to use mustard oil in my dishes, correct?” Unsure of exactly what she was asking, I asked her why that would be the case. “Well,” she said, “because it’s illegal”. I was confused. I had never heard of mustard oil before and I definitely hadn’t heard of an illegal cooking oil before. What could possibly be illegal about it? Was it highly combustable? Were there new sanctions on Pakistan that I hadn’t heard about? Maybe it was toxic to pets. Nevertheless, I assured her I would look into her question and get back to her.

Mustard oil is a bright, pungent oil made from pressing the seeds of the mustard plant to release an oil that is relished in many countries for its unique spiciness and high smoking point of 480F (Sharma, 2020). It’s most popularly used as a cooking oil or condiment in the cuisines of East and Central Asian countries such as China, Bangladesh, and India, but also appears in some dishes in Russian and other Baltic cuisines. It’s particularly popular in the northern state of West Bengal in India, where it’s used in dishes such as achaars, a pickled condiment used to add an acidic spice to a wide variety of dishes. One difference that you might see as you traverse Asia is the type of mustard seed being used to make mustard oil. In India, black mustard seeds from the plant Brassica nigra are used to make the oil, while brown mustard seeds from Brassica juncea are more commonly used in China and Russian oils (2020). However, the controversy behind mustard oil lies deeper into the biology of the mustard plant and Brassicaceae family in general, specifically with a long-chain fatty acid called erucic acid.

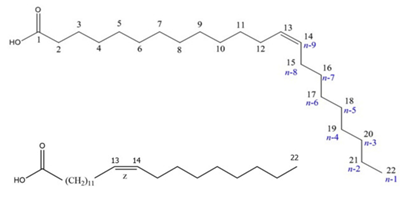

Erucic acid is a naturally-occuring, non-branched, monounsaturated fatty acid with 22 carbons and a cis-configured double bond on the 13th carbon (Vetter et al., 2020). The Brassicacea family of plants, often referred to as the Cruciferae or mustard family (Šamec et al., 2019) includes vegetables that are highly consumed all across the world, such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbages, and of course mustard greens. Additionally due to their high fat content, many species of fish, such as wild salmon, also contain measurable levels of erucic acid (Vetter et al., 2020). While mustard oil is comprised of a variety of fatty acids, erucic acid can sometimes comprise up to 50% of an oil’s fatty acid composition, causing it to be a liquid at room temperature (Wendlinger et al., 2013). It’s because of this high concentration of erucic acid in the fatty acid composition that makes mustard oil such a controversial ingredient, as many of the other members of the Brassicaceae family tend to have much lower overall levels.

Discussion around the potential toxicity of erucic acid first began in the 1950’s when research began to surface showing a potential link between high levels of erucic acid consumption in rats and the development of myocardial lipidosis and heart lesions (2013). In one of the studies, fully refined rapeseed oils (another oil with a high concentration of erucic acid) containing different amounts of erucic acid from 1.6% to 22.3% were fed, at 20% by weight of diet, to weanling male and female rats for periods up to 112 days.. Myocardial lipidosi, a temporary, reversible heart condition was seen in rats that had been fed oxidized and unoxidized rapeseed oil containing 22.3% erucic acid, moderate with rapeseed oil containing 4.3% erucic acid and very slight in rats fed rapeseed oil containing 1.6% erucic acid (2013). Its most serious detrimental health effects were determined to be high triacylglycerol accumulation in the heart due to insufficient oxidation, which could possibly result in a reduced ability for the heart muscle to function (2013). In other words, the lower the concentration of erucic acid in the rapeseed oil a rat was fed, the less likely they were to develop heart conditions.

At the same time that these studies were being produced, work was being done by scientists and manufacturers in Canada to develop a “heart healthy” cooking oil that was low in erucic acid. Through careful breeding processes, the group of scientists were able to produce rapeseed plants with low levels of erucic acid. The oil, later to be named canola oil (can- for Canada, -ola which stands for “oil, low acid”) soon became a commercialized, easily marketable hit with both the public and science community alike (Fisher, 2020). The question then became, is the risk worth the reward?

The regulations on mustard oil began in 1976 when the EU introduced a maximum level of 5% erucic acid contribution to the total fatty acids in edible oils and added fats (Vetter et al., 2020). 16 years later, the U.S. followed suit in the 1990’s when the FDA banned the import and sale of mustard oil as foodstuffs (Sen, 2011). External uses of the product, such as for massage oil, were still viewed as acceptable. Most recently in 2016, the FDA released Import Alert #26-04 which stated that “[M]ustard oil is not permitted for use as a vegetable oil. It may contain 20 to 40% erucic acid, which has been shown to cause nutritional deficiencies and cardiac lesions in test animals” (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2016). Additionally, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) released a report in 2016 suggesting the decrease of the acceptable maximum level from 5% down to 2% of the total fatty acid composition (Vetter et al., 2020).

All in all, things haven’t looked good for mustard oil and its devoted fans since the 1950’s, despite there not being any presence of evidence or work towards researching that high concentrations of erucic acid would have negative health consequences on human beings, not just lab rats. When I first learned about the banning of mustard oil, I was fairly frustrated. The use of this type of incomplete research on laws and regulations can have widespread negative effects on the greater population if not properly reexamined over time. With so many Southeast Asian cuisines relying on the inclusion of mustard oil to create some of their most beloved dishes, a banning of the substance inherently creates a lack of accessibility for specific populations that immigrate to any country where the ingredient is banned. While yes, mustard oil can still be sold in stores, it must don a “For External Use Only” label on it in order to be purchased, forcing a narrative on its consumers that they as an entire population eat ingredients that are not deemed to be edible by greater science. When these consequences are then balanced with the fact that the laws and regulations around mustard oil were based off of decades-old research that was performed on laboratory rats, the ends in no way seem to justify the means.

While there has been some progress towards a better understanding of the importance of mustard oil (the very first refined, single-ingredient mustard oil called recently became approved by the FDA in 2016 (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2016)), there still is much work to be done in understanding the cultural and societal consequences in banning particular foodstuffs and ingredients, specifically when the research is outdated or incomplete. What can be learned from mustard oil’s struggle for acceptance is an overall better understanding of the holistic impacts on food safety decisions and what they inherently say about a specific culture, cuisine, or population.

Works Cited

Charlton, K M, A H Corner, K Davey, J K Kramer, S Mahadevan, and F D Sauer. “Cardiac Lesions in Rats Fed Rapeseed Oils.” Canadian journal of comparative medicine : Revue canadienne de medecine comparee. U.S. National Library of Medicine, July 1975. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1277456/.

“Erucic Acid a Possible Health Risk for Highly Exposed Children.” European Food Safety Authority. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/press/news/161109#:~:text=Tests%20on%20animals%20show%20that,occur%20at%20slightly%20higher%20doses.

Fisher, Ben. “The Real Reason Mustard Oil Is Banned for Cooking Purposes in the U.S.” Mashed.com. Mashed, July 22, 2020. https://www.mashed.com/228910/the-real-reason-mustard-oil-is-banned-for-cooking-purposes-in-the-u-s/.

“Import Alert 26-04.” accessdata.fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration, November 18, 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cms_ia/importalert_89.html.

Sen, Indrani. “American Chefs Discover Mustard Oil.” The New York Times. The New York Times, November 1, 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/02/dining/american-chefs-discover-mustard-oil.html.

Sharma, Nik. “The Truth about Mustard Oil: Behind the ‘for External Use Only’ Label.” Serious Eats. Serious Eats, September 11, 2020. https://www.seriouseats.com/mustard-oil-guide.

Vetter, Walter, Vanessa Darwisch, and Katja Lehnert. “Erucic Acid in Brassicaceae and Salmon – an Evaluation of the New Proposed Limits of Erucic Acid in Food.” NFS Journal 19 (2020): 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nfs.2020.03.002.

Vles, R. O., G. M. Bijster, and W. G. Timmer. “Nutritional Evaluation of Low-Erucic-Acid Rapeseed Oils.” SpringerLink. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, January 1, 1978. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-66896-8_3.

Šamec, Dunja, and Branka Salopek-Sondi. “Cruciferous (Brassicaceae) Vegetables.” Nonvitamin and Nonmineral Nutritional Supplements. Academic Press, October 5, 2018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128124918000278.

To Eat or Not to Eat: The Persistent Questionability of MSG

This month we will be featuring a series of posts from student's in MET ML 619, The Science of Food and Cooking, with Professor Valerie Ryan. Today's post is submitted by Gastronomy student María José Córdova.

Is MSG a Chemical?

Over one hundred years since its isolation and fifty years since the “discovery” of the Chinese Restaurant Syndrome (CRS), the safety and status of monosodium glutamate (MSG) remains debatable among laypeople. Initial distrust of MSG’s safety may have been fueled by both chemophobia and xenophobia, but the reason for its persistence appears to be less clear. Negative attitudes about MSG are often based on a legacy of misunderstanding and misinformation. Here, I endeavor to develop an overview of MSG’s origins, chemistry, and production that may better inform the individual’s opinion on MSG and dispel some lingering mistrust.

The Chemistry

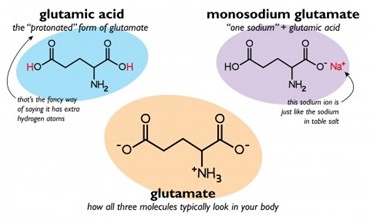

MSG is the sodium salt of glutamic acid (Wang & Adhikari 2018). Glutamate is a naturally occurring amino acid that dissolves into free glutamic acid. Free glutamate is found in a variety of foods like tomatoes, parmesan cheese, and seaweed and is naturally found in our bodies (Taliaferro 1995). Glutamic acid is a nonessential amino acid with a variety of functions, one of which is to act as a neurotransmitter.

In 1908, Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda succeeded in isolating glutamic acid and identifying it as responsible for the savory taste of konbu dashi (sea kelp broth). Ikeda called this taste umami and proceeded to develop a crystalline powder via a chemical process. Thus emerged monosodium glutamate, which Ikeda patented and later founded Ajinomoto, a company that continues to mass-produce MSG today (Ikeda 2002).

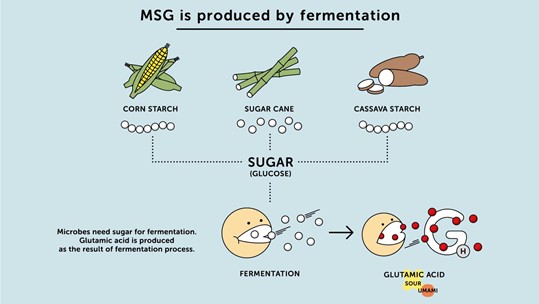

Various methods exist for producing MSG. The most common way to produce MSG today is through the fermentation of plant-based ingredients like sugar cane or corn (Ault 2004, Sand 2005). According to the Ajinomoto website, after the fermentation process produces glutamic acid, the solution is decolorized, filtered, and crystallized, yielding the MSG powder that we recognize (“What is MSG and how is it made?”). This is the powder that made its way into many foods across the U.S. food supply for decades before facing questions about its safety.

The MSG Symptom Complex

In 1968, the New England Journal of Medicine published a letter from Chinese American doctor Robert Ho Man Kwok entitled “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” in 1968. Kwok’s letter described a syndrome which produced “a numbness at the back of the neck, gradually radiating to both arms and the back, general weakness and palpitations” (796). While Kwok’s letter is not definitive about MSG’s causal role in producing these symptoms, he does isolate this experience to dining at Chinese restaurants and coins the term “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” (CRS). The following month after Kwok’s letter was published, The New England Journal of Medicine published eleven different correspondences on CRS that express relief and identify with Kwok’s experience. Few suspect MSG is the cause. Instead, they focus on the experience occurring after consuming food at Chinese restaurants (1968, 1122-1124). The first of these correspondences is from H. Schaumburg, a professor of neurology who published a study on the effects of MSG the following year. His research both legitimized CRS as a medical condition and determined MSG was the cause. Schaumburg also pointed out that MSG was widely used as a food additive which widened the scope of the issue beyond Chinese restaurants (Mosby 2009). While Schaumburg’s and other subsequent studies have since been questioned or delegitimized for their faulty methodologies, their legacy persists.

Anti-MSG attitudes in the United States are associated with medical ailments and racialized with terms like “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” (CRS). It becomes difficult to separate anti-MSG campaigns from anti-Asian ones. In the U.S., there exists a long history of systemic xenophobia, first codified with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (Wahlstedt et al. 2022). To specifically associate MSG with Chinese cuisine when it had been used for decades in processed food is indicative of xenophobic bias by medical professionals. Moreover, media seized upon the early correspondences to spread misinformation that was, up to this point, based on anecdotal evidence. However, today we see consumer preference for natural foods and a fear of chemicals continues to fuel a mistrust of MSG.

The Chemophobia

While there is scientific consensus that MSG is not unsafe, studies on consumer attitudes demonstrate that negative attitudes toward MSG are shaped by consumers’ chemophobia and misinformation about MSG (Wang and Adhikari, 2018). Several studies also show that many of the initial studies performed on MSG produced questionable results based on flawed methodology (Freeman 2006; Geha et al. 2000; Taliaferro 1995; Wahlstedt et al. 2022).

In the simplest terms, chemophobia is the fear of chemicals. In “Food Chemistry and Chemophobia,” Gordon W. Gribble suggests that the advent of chemophobia occurred in the wake of Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ and the environmental movements of the era. Such reports moved the public to distrust the chemical industry. Gribble argues that, ultimately, everything we “see, smell, and touch is chemical!” and that the media uses the terms aroma, bouquet, fragrance, and odor are euphemisms for the volatile chemicals we breath (2013, 178). For Gribble, the breakdown of everything around us into molecules renders it a chemical because of chemistry. Moreover, he believes that “The Dose Makes the Poison” and argues that, in excess, the ingestion of natural compounds like water or salt are fatal.

While Gribble’s approach is extreme, it is evidence-based and works to reset the baseline for what is chemical and what makes a chemical dangerous. Gribble does not discuss MSG, but his argument touches on the tension between natural and artificial chemistry. Wang and Adhikari’s study on consumer perceptions about MSG concluded that subjects with a preference for natural food were more concerned about MSG which coincided with a general fear of chemicals. Additionally, the researchers found that many of their subjects misunderstood the function of MSG and believed it to be high in sodium when it contains less sodium than sodium chloride (2018).

Contemporary articles on MSG and its safety tend to agree that MSG has been misconstrued to be seen as unsafe due to misinformation and a history of questionable research methodologies, both of which contribute to the public’s mistrust of MSG.

Future Research

As of now, scientific research has not proved that MSG is bad for our health. Studies performed in the wake of Kwok’s original correspondence have since been discredited for only testing a handful of subjects that produced biased results. Anti-MSG messaging has largely been based on misinformation and personal experiences and xenophobic responses. However, this cultural response has had a long-lasting impact on American attitudes towards MSG. In recent years, anti-MSG sentiment stems more from chemophobia, yet the impact is similar because of the historical link between MSG and anti-Asian attitudes.

Future research should endeavor to explore a more nuanced approach to the bias against MSG and the link between consumer’s attitudes and cultural bias. Such a study may be more subjective but could illuminate whether anti-Asian sentiments continue to affect consumers’ opinion on MSG and perhaps where consumers first met anti-MSG messaging. As has been overviewed here, anti-MSG attitudes have largely been shaped by a serious of unfortunate events that sowed distrust while also capitalizing on anti-Asian xenophobia. Such a legacy is difficult to undo but doing so would leave the public better suited to understand their implicit bias, its origins, and ways to move forward.

Works Cited

Ault, Addison. "The Monosodium Glutamate Story: The Commercial Production of MSG and Other Amino Acids." Journal of Chemical Education 81, no. 3 (2004): 347-55.

Freeman, Matthew. “Reconsidering the Effects of Monosodium Glutamate: A Literature Review.” Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 18, no. 10 (2006): 482–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00160.x

Geha, Beiser, A., Corren, J., Saxon, A., Ren, C., Patterson, R., Greenberger, P. A., Grammer, L. C., Ditto, A. M., Harris, K. E., Shaughnessy, M. A., & Yarnold, P. R. “Review of alleged reaction to Monosodium glutamate and outcome of a multicenter double-blind placebo-controlled study.” The Journal of Nutrition, 130 (4), (2000): 1058S–1062S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/130.4.1058S

Gribble, G.W. “Food chemistry and chemophobia.” Food Security. 5, no. 2 (2013): 177–187. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1007/s12571-013-0251-2

Ikeda, Kikunae. 2002. “New Seasonings.” Chemical Senses, 27, 847-849.

Kwok, R. H. “Chinese-restaurant syndrome." New England Journal of Medicine. 278, no. 14 (1968):796.

Mosby, Ian. “‘That Won-Ton Soup Headache’: The Chinese Restaurant Syndrome, MSG and the Making of American Food, 1968–1980.” Social History of Medicine: The Journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine 22, no. 1 (2009): 133–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkn098

Sand, Jordan. “A Short History of MSG: Good Science, Bad Science, and Taste Cultures.” Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture, 5, no. 4 (2005): 38-49.

Schaumburg, H. "Chinese-Restaurant Syndrome." The New England Journal of Medicine 278, no. 20 (1968): 1122-124.

Taliaferro, Patricia J. “Monosodium glutamate and the Chinese Restaurant Syndrome: a review of food additive safety.” Journal of Environmental Health, 57, no. 10 (1995): 8-12.

Wahlstedt, Amanda, Elizabeth Bradley, Juan Castillo, and Kate Gardner Burt. "MSG Is A-OK: Exploring the Xenophobic History of and Best Practices for Consuming Monosodium Glutamate." Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 122, no. 1 (2022): 25-29.

Wang, Shangci and Koushik Adhikari. "Consumer Perceptions and Other Influencing Factors about Monosodium Glutamate in the United States." Journal of Sensory Studies 33, no. 4 (2018): e12437-n/a. doi:10.1111/joss.12437.

Pots and Pans, Bodkins and Trowels: Reflections on Mary Beaudry

The Gastronomy community is invited to register for this symposium to be held on Saturday April 30, 1 pm to 6 pm. Registration is available for in person attendance or via zoom.

The Gastronomy community is invited to register for this symposium to be held on Saturday April 30, 1 pm to 6 pm. Registration is available for in person attendance or via zoom.

Dr. Mary C. Beaudry (1950-2020) was an influential scholar, professor, and beloved fixture of Boston archaeology. This symposium brings together speakers and panelists who will discuss Dr. Beaudry’s scholarly legacy across a range of disciplines and at the points of intersection between them: gastronomy and culinary arts, the archaeology and history of food, anthropology, material culture studies, museum studies, women’s studies, preservation studies, and American studies.

Through our invited speakers and a panel discussion, we will explore Dr. Beaudry’s contributions and continuing influence in our work, from small finds and object biographies, to the sensoriality and materiality of dining, to examinations of landscape and architecture, to telling stories about daily life using everyday objects and spaces.

Program:

1:00 Welcome and Introductory Remarks, Karen Metheny

1:10 The Interdisciplinary Life of Mary Beaudry, Rebecca Alssid

1:30 Pots, Pans, and Stills: Millet's Ancient Journey from Nile, Veneto, and Whole Foods, James McCann

1:50 Bodkins, Beads, and Buttons: Dressing the Part in 17th-Century Massachusetts, Diana Loren

2:25 Pots, Pans, and Labor: A Birds-Eye View of the History of the Kitchen in America, Nancy Carlisle

2:45 Finding Feminist Meaning in Cooking and its History , Barbara Haber

3:05 Discussion

3:30 Panel Discussion: David Carballo, Edward L. Bell, Ann-Eliza Lewis, Daniel Wilson, and Stephen A. Mrozowski, Megan J. Elias, discussant, Millie Rahn, moderator

4:45 Life with Mary: Tales and Tributes, with a recorded tribute from Jacques Pépin, Merry White, moderator

5:00 Reception and a toast to Mary

Spring 2022 Pépin Lecture Series in Food Studies & Gastronomy

Spring 2022 lectures will be presented in webinar format. Registration is free and open to the public - please follow the link for each program to register.

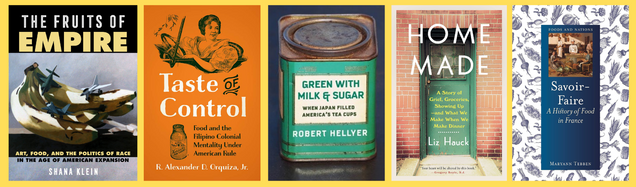

The Fruits of Empire Art, Food, and the Politics of Race in the Age of American Expansion

Friday, February 11 at 12 pm EST

Shana Klein Reisig, Assistant Professor of Art History at Kent State University

The Fruits of Empire is a history of American expansion through the lens of art and food. In the decades after the Civil War, Americans consumed an unprecedented amount of fruit as it grew more accessible with advancements in refrigeration and transportation technologies. This excitement for fruit manifested in an explosion of fruit imagery within still life paintings, prints, trade cards, and more. Images of fruit labor and consumption by immigrants and people of color also gained visibility, merging alongside the efforts of expansionists to assimilate land and, in some cases, people into the national body. Divided into five chapters on visual images of the grape, orange, watermelon, banana, and pineapple, this book demonstrates how representations of fruit struck the nerve of the nation’s most heated debates over land, race, and citizenship in the age of high imperialism.

The Fruits of Empire is a history of American expansion through the lens of art and food. In the decades after the Civil War, Americans consumed an unprecedented amount of fruit as it grew more accessible with advancements in refrigeration and transportation technologies. This excitement for fruit manifested in an explosion of fruit imagery within still life paintings, prints, trade cards, and more. Images of fruit labor and consumption by immigrants and people of color also gained visibility, merging alongside the efforts of expansionists to assimilate land and, in some cases, people into the national body. Divided into five chapters on visual images of the grape, orange, watermelon, banana, and pineapple, this book demonstrates how representations of fruit struck the nerve of the nation’s most heated debates over land, race, and citizenship in the age of high imperialism.

Taste of Control: Food and the Filipino Colonial Mentality Under American Rule

Friday, March 18, 12 pm EST

Alexander Orquiza, Associate Professor, Department of History and Classics, Providence College

Filipino cuisine is a delicious fusion of foreign influences, adopted and transformed into its own unique flavor. But to the Americans who came to colonize the islands in the 1890s, it was considered inferior and lacking in nutrition. Changing the food of the Philippines was part of a war on culture led by Americans as they attempted to shape the islands into a reflection of their home country.

Filipino cuisine is a delicious fusion of foreign influences, adopted and transformed into its own unique flavor. But to the Americans who came to colonize the islands in the 1890s, it was considered inferior and lacking in nutrition. Changing the food of the Philippines was part of a war on culture led by Americans as they attempted to shape the islands into a reflection of their home country.

Taste of Control tells what happened when American colonizers began to influence what Filipinos ate, how they cooked, and how they perceived their national cuisine. Food historian René Alexander D. Orquiza, Jr. turns to a variety of rare archival sources to track these changing attitudes, including the letters written by American soldiers, the cosmopolitan menus prepared by Manila restaurants, and the textbooks used in local home economics classes. He also uncovers pockets of resistance to the colonial project, as Filipino cookbooks provided a defense of the nation’s traditional cuisine and culture.

Through the topic of food, Taste of Control explores how, despite lasting less than fifty years, the American colonial occupation of the Philippines left psychological scars that have not yet completely healed, leading many Filipinos to believe that their traditional cooking practices, crops, and tastes were inferior. We are what we eat, and this book reveals how food culture served as a battleground over Filipino identity

Green with Milk and Sugar: When Japan Filled America’s Tea Cups

Friday, April 1 at 12 pm EST: In person at 808 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston MA, or online via zoom.

Robert Hellyer, Associate Professor of History, Wake Forest University.

Today, Americans are some of the world’s biggest consumers of black teas; in Japan, green tea, especially sencha, is preferred. These national partialities, Robert Hellyer reveals, are deeply entwined. Tracing the trans-Pacific tea trade from the eighteenth century onward, Green with Milk and Sugar shows how interconnections between Japan and the United States have influenced the daily habits of people in both countries.

Today, Americans are some of the world’s biggest consumers of black teas; in Japan, green tea, especially sencha, is preferred. These national partialities, Robert Hellyer reveals, are deeply entwined. Tracing the trans-Pacific tea trade from the eighteenth century onward, Green with Milk and Sugar shows how interconnections between Japan and the United States have influenced the daily habits of people in both countries.

Hellyer explores the forgotten American penchant for Japanese green tea and how it shaped Japanese tastes. In the nineteenth century, Americans favored green teas, which were imported from China until Japan developed an export industry centered on the United States. The influx of Japanese imports democratized green tea: Americans of all classes, particularly Midwesterners, made it their daily beverage—which they drank hot, often with milk and sugar. In the 1920s, socioeconomic trends and racial prejudices pushed Americans toward black teas from Ceylon and India. Facing a glut, Japanese merchants aggressively marketed sencha on their home and imperial markets, transforming it into an icon of Japanese culture.

Featuring lively stories of the people involved in the tea trade—including samurai turned tea farmers and Hellyer’s own ancestors—Green with Milk and Sugar offers not only a social and commodity history of tea in the United States and Japan but also new insights into how national customs have profound if often hidden international dimensions.

Home Made: A Story of Grief, Groceries, Showing Up — and What We Make When We Make Dinner

Friday, April 15 at 12:00 pm EST

Liz Hauck is an educator and writer from Boston, Massachusetts. She is completing a Ph.D. in educational policy studies and history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Liz Hauck and her dad had a plan to start a weekly cooking program in a residential home for teenage boys in state care, which was run by the human services agency he co-directed. When her father died before they had a chance to get the project started, Liz decided she would try it without him. She didn’t know what to expect from volunteering with court-involved youth, but as a high school teacher she knew that teenagers are drawn to food-related activities, and as a daughter, she believed that if she and the kids made even a single dinner together she could check one box off of her father’s long, unfinished to-do list. This is the story of what happened around the table, and how one dinner became one hundred dinners.

Liz Hauck and her dad had a plan to start a weekly cooking program in a residential home for teenage boys in state care, which was run by the human services agency he co-directed. When her father died before they had a chance to get the project started, Liz decided she would try it without him. She didn’t know what to expect from volunteering with court-involved youth, but as a high school teacher she knew that teenagers are drawn to food-related activities, and as a daughter, she believed that if she and the kids made even a single dinner together she could check one box off of her father’s long, unfinished to-do list. This is the story of what happened around the table, and how one dinner became one hundred dinners.

“The kids picked the menus, I bought the groceries,” Liz writes, “and we cooked and ate dinner together for two hours a week for nearly three years. Sometimes improvisation in kitchens is disastrous. But sometimes, a combination of elements produces something spectacularly unexpected. I think that’s why, when we don’t know what else to do, we feed our neighbors.”Capturing the clumsy choreography of cooking with other people, this is a sharply observed story about the ways we behave when we are hungry and the conversations that happen at the intersections of flavor and memory, vulnerability and strength, grief and connection.

Capturing the clumsy choreography of cooking with other people, this is a sharply observed story about the ways we behave when we are hungry and the conversations that happen at the intersections of flavor and memory, vulnerability and strength, grief and connection.

Savoir-Faire: A History of Food in France

Friday, April 29 at 12 pm EST

Maryann Tebben is Professor of French and Head of the Center for Food Studies at Bard College at Simon's Rock.

Savoir-Faire is a comprehensive account of France’s rich culinary history, which is not only full of tales of haute cuisine, but seasoned with myths and stories from a wide variety of times and places—from snail hunting in Burgundy to female chefs in Lyon, and from cheese appreciation in Roman Gaul to bread debates from the Middle Ages to the present. It examines the use of less familiar ingredients such as chestnuts, couscous, and oysters; explores French food in literature and film; reveals the influence of France’s overseas territories on the shape of French cuisine today; and includes historical recipes for readers to try at home.

We thank the Jacques Pépin Foundation for sponsorship of this lecture series.

Welcome New Gastronomy and Food Studies Students, Spring 2022 part 2

We look forward to welcoming a wonderful group of new students into our programs this spring. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Amanda Leavitt: I’ve loved food since the second my godmother propped me on a stool in the kitchen to learn about the art of the vinaigrette, so while earning my BS in Communications at Boston University, I found myself immersed in numerous food businesses. My professional experiences include working food retail at my family’s business in Puerto Rico, hosting in a fine dining restaurant, making chickpea fritter sandwiches on a Clover Food Truck, and leading chocolate tastings out of a boutique in Copley Square. All of this allowed me to use my love for communication and my love for food simultaneously. One of my most treasured professional experiences was working for the Jamie Oliver Food Foundation in London, whose mission was to make cooking accessible to everyone. I currently work for a restaurant tech company in Boston, where I’m constantly interacting with restaurant owners. My biggest goal is to fully immerse myself in all things food. When I’m not working or studying, I can be found making cooking videos, lately of Salvadoran or Puerto Rican food. If you need a good curtido or tostones recipe, I’ve got you!

Amanda Leavitt: I’ve loved food since the second my godmother propped me on a stool in the kitchen to learn about the art of the vinaigrette, so while earning my BS in Communications at Boston University, I found myself immersed in numerous food businesses. My professional experiences include working food retail at my family’s business in Puerto Rico, hosting in a fine dining restaurant, making chickpea fritter sandwiches on a Clover Food Truck, and leading chocolate tastings out of a boutique in Copley Square. All of this allowed me to use my love for communication and my love for food simultaneously. One of my most treasured professional experiences was working for the Jamie Oliver Food Foundation in London, whose mission was to make cooking accessible to everyone. I currently work for a restaurant tech company in Boston, where I’m constantly interacting with restaurant owners. My biggest goal is to fully immerse myself in all things food. When I’m not working or studying, I can be found making cooking videos, lately of Salvadoran or Puerto Rican food. If you need a good curtido or tostones recipe, I’ve got you!

My name is Michael O’Brien and I am currently working as an legal counsel for the Department of Housing and Urban Development. I returned to New England after obtaining a degree in political science from the University of Alabama, 5 years of service in the Army in North Carolina and most recently obtaining my law degree from the University of Georgia. Needless to say, I have had my fill and then some of BBQ and Hushpuppies.

My name is Michael O’Brien and I am currently working as an legal counsel for the Department of Housing and Urban Development. I returned to New England after obtaining a degree in political science from the University of Alabama, 5 years of service in the Army in North Carolina and most recently obtaining my law degree from the University of Georgia. Needless to say, I have had my fill and then some of BBQ and Hushpuppies.

I have always found the way that food and drink is able to connect people to be fascinating. Strangers at a bar can become best friends for hours thanks to a few glasses of bourbon, never to see each other again. In Afghanistan, meetings with local leaders were often held over meals, bonding those at the table if only for a short period of time. Food is universal…unless it’s black licorice.

While I do hold onto a dim dream of one day opening my own Brewpub restaurant, I think I simply came to the Gastronomy program to learn as much as I can about food. Where it originated, how it came to be made the way that it is, what wine pairs well with what dishes. I look forward to soaking in everything like a sponge and coming out with a better understanding and appreciation of food!

Leslie Tente is a retired elementary school teacher, and resides in the village of Rumford, Rhode Island. Given her passion for cooking, baking, and culinary history, it almost seemed ordained that she settled in Rumford with her husband and daughter as it was in this section of East Providence that Rumford Baking Powder was first manufactured. Rumford at one time was referred to as “the kitchen capital of the world," and the kitchen has always been the center of Leslie's home!

Leslie Tente is a retired elementary school teacher, and resides in the village of Rumford, Rhode Island. Given her passion for cooking, baking, and culinary history, it almost seemed ordained that she settled in Rumford with her husband and daughter as it was in this section of East Providence that Rumford Baking Powder was first manufactured. Rumford at one time was referred to as “the kitchen capital of the world," and the kitchen has always been the center of Leslie's home!

After leaving her teaching career, Leslie's interest in culinary history deepened through her volunteer work with the East Providence Historical Society. Leslie takes great pleasure in sharing the rich culinary history of Rumford Baking Powder with visitors to the John Hunt House, the historical society's house museum.

In 2019, Leslie organized The Great Rumford Bake Off in celebration of Rumford Baking Powder's 160th Anniversary. The Bake Off attracted enthusiastic amateur bakers from all over New England, and it was during this joyous event that Leslie knew she wanted to take her volunteer work to a more scholarly level.

Leslie is excited to begin her journey in the Food Studies/Gastronomy program and looks forward to meeting and learning from all of the amazing students and faculty in the department.

Heather Yeatman: “What can I eat?” For some people, this question is easily answered by opening the fridge or their favorite food delivery app. For someone like me, this is a very real dilemma that can cause physical distress and require mental gymnastics. I’ve always had a love of food, but the affair soured in 2013 after a series of emergency abdominal surgeries triggered a combination of new food allergies. My body no longer properly processes dairy, gluten, beans, tamarind, or whole corn, and tree nuts are my kryptonite. So I had to find new ways of cooking and eating, and these joyful challenges are now my creative outlet.

Heather Yeatman: “What can I eat?” For some people, this question is easily answered by opening the fridge or their favorite food delivery app. For someone like me, this is a very real dilemma that can cause physical distress and require mental gymnastics. I’ve always had a love of food, but the affair soured in 2013 after a series of emergency abdominal surgeries triggered a combination of new food allergies. My body no longer properly processes dairy, gluten, beans, tamarind, or whole corn, and tree nuts are my kryptonite. So I had to find new ways of cooking and eating, and these joyful challenges are now my creative outlet.

As I've honed my skills in the kitchen to become a better chef, I’ve helped numerous friends and family learn to prepare and enjoy dishes they previously had to “give up.” In our house, no one goes hungry. Want a gluten-free, dairy-free tiramisu an Italian grandmother would be happy to devour? I got you. So many cuisines of the world are safe and enjoyable for those of us with food allergies if one expands their palate, and others can be made simply by substituting the right ingredients. I love exploring the culinary map, finding new options, and sharing them with my fellow foodies for whom allergies are a daily obstacle.

Limitations place foodies in one of two categories: 1) Disenchantment and diminishing desire for food, or 2) Relishing the challenge and finding joy in a varied way of eating. I’ve chosen the latter, and it’s my goal to help others like me to do the same. My own journey back to food is chronicled in the beginnings of a website and small social network following on Instagram and Facebook where I answer the burning question, “WTF Can I Eat?!”. Just as I’ll always be learning new cooking techniques, I also need to learn new ways of reaching a wider audience to help more people. I look forward to being a student of BU-MET’s Gastronomy program to gain the tools and knowledge needed to achieve my goals and a better understanding of cultural tourism and food philosophy. You can usually find me traveling to new locales, storming castles, or hiking the lush forest trails behind our house here in Germany.

Welcome New Students, Spring 2022!

We look forward to welcoming a wonderful group of new students into our programs this spring. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Ana Acevedo-Barga Whether brewing fresh coffee, baking up a hot batch of chocolate chip cookies, or serving a 20-course meal, my delight in the experience of dining is everlasting. Food is magic! I have spent the past decade working in the food service industry, sharing my love for delectable cuisine and warming hospitality. My most recent years have been at o ya, a Japanese inspired restaurant in Boston, specializing in weaving flavor and texture into a mouthwatering journey. My work in fine dining has led me here, eager to explore food beyond its relationship to the restaurant industry. I look forward to studying the intersections between agriculture, history, society, economics and food. With my masters I hope to deepen my understanding of these origins of food and food practices in order to better contribute (and hopefully improve) the ever-evolving world of dining and hospitality.

Ana Acevedo-Barga Whether brewing fresh coffee, baking up a hot batch of chocolate chip cookies, or serving a 20-course meal, my delight in the experience of dining is everlasting. Food is magic! I have spent the past decade working in the food service industry, sharing my love for delectable cuisine and warming hospitality. My most recent years have been at o ya, a Japanese inspired restaurant in Boston, specializing in weaving flavor and texture into a mouthwatering journey. My work in fine dining has led me here, eager to explore food beyond its relationship to the restaurant industry. I look forward to studying the intersections between agriculture, history, society, economics and food. With my masters I hope to deepen my understanding of these origins of food and food practices in order to better contribute (and hopefully improve) the ever-evolving world of dining and hospitality.

Chad Bradford: Some time ago, I realized that every conversation with me, no matter how it started, somehow ended up being about food. They say they've got the latest gadget. The freshest beats. Water on the moon. Gastronomers, you know what I'm thinking. "Great, but will there be pizza?" That's why I was so excited to find the Gastronomy program at BU and a group of like-minded folks. We get it!

Chad Bradford: Some time ago, I realized that every conversation with me, no matter how it started, somehow ended up being about food. They say they've got the latest gadget. The freshest beats. Water on the moon. Gastronomers, you know what I'm thinking. "Great, but will there be pizza?" That's why I was so excited to find the Gastronomy program at BU and a group of like-minded folks. We get it!

I retired in October 2021, but I am not yet ready to "retire" retire. I have developed an interest in how food affects bodies and spirits and want to learn more about the connections.

You will usually find me somewhere asking for seconds, running long trails, or enjoying work from home tea time with my wife.

Liz Lauren-Oser: I hold a master’s in Liberal Studies. As a teacher I taught my students that History is really just the story of people living in another time and it is a story very much like their own.

Liz Lauren-Oser: I hold a master’s in Liberal Studies. As a teacher I taught my students that History is really just the story of people living in another time and it is a story very much like their own.

I collect cookbooks and recipes, especially (any) family recipes. Family recipes are often the glue that holds people together, binding them to their history. A recipe can perpetuate the warm memory of a beloved relative and can connect one generation to another. The food created from that recipe can offer not just physical saity, but an emotional connection.

I discovered this program after watching a lecture about Victorian Christmases. A food historian was part of the panel and at that moment I realized I could combine my interest in people’s stories and history with my love of cookbooks and recipes. Food and recipes are not just about physical nourishment, but snapshots of history, too. My dream job would be to become a food historian.

In my real life I am a wife, a mom to four adults and grandmother (BeBe) to four of the most remarkable humans I have ever encountered. I garden, take long walks and most of all, cook.

Stephanie Monserrate was born in Puerto Rico. She is a Project Manager and a former French and Portuguese Professor. Her interdisciplinary academic background granted her a bachelor degree in Latin American History with a Minor in Foreign Language Education. Her multiple passions made her pursue a Master Degree in Cultural Agency and Arts Administration. At the present she is interested in the different meanings and representations of food in our daily rituals. And how food fill the silences that we avoid.This new path brings her in to the Master of Arts in Gastronomy Program at Boston University’s Metropolitan College.

Stephanie Monserrate was born in Puerto Rico. She is a Project Manager and a former French and Portuguese Professor. Her interdisciplinary academic background granted her a bachelor degree in Latin American History with a Minor in Foreign Language Education. Her multiple passions made her pursue a Master Degree in Cultural Agency and Arts Administration. At the present she is interested in the different meanings and representations of food in our daily rituals. And how food fill the silences that we avoid.This new path brings her in to the Master of Arts in Gastronomy Program at Boston University’s Metropolitan College.

Siobhan O’Flaherty, a Boston native, is thrilled to join BU’s Gastronomy program after transferring from NYU. Siobhan’s journey to food studies began at her community garden in Brooklyn. A dedicated member, she fell in love with growing vegetables from seed, cooking her own harvest, and the deep bonds she forged with her community.

Siobhan O’Flaherty, a Boston native, is thrilled to join BU’s Gastronomy program after transferring from NYU. Siobhan’s journey to food studies began at her community garden in Brooklyn. A dedicated member, she fell in love with growing vegetables from seed, cooking her own harvest, and the deep bonds she forged with her community.

Upon returning home during the pandemic, she joined the field crew at Barrett’s Mill Farm, a women-owned, 15-acre organic vegetable farm in Concord. She is now spending the “off-season” in the produce department at Volante Farms in Needham. She continues her decades-long commitment to community service by volunteering weekly at her local food pantry.

Siobhan remains an avid gardener and spent her first year of grad school saving heritage seeds from Ireland and Portugal. She would love to connect with other BU students who are interested in seed keeping and sustainable agriculture. When she isn’t playing in the dirt, Siobhan is probably taking a walk while listening to a podcast.

My name is Sara Sobkoviak and I am a passionate teacher, foodie, traveler, and learner. I received my bachelor’s degree 20 years ago in Mass Media Communications from Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma and I minored in Spanish. I then went on to work in the photography industry and started my own business where I photographed families, individuals, engagements, and weddings (including countless Indian weddings where I sampled many amazing dishes). I have traveled to many Spanish-speaking countries and have been heavily influenced by their cultures and food practices. My interest in food has grown since I was a child in my mother’s kitchen in a small town in Illinois. I continued my passion for food by working in restaurants, for catering companies, and then studying culinary arts near my current home in California. My experiences in these kitchens have taught me so much about the culinary world, and the knowledge I now possess is one that I pass on to my high school students in an “Adulting” program I created. Beyond teaching Spanish and culinary skills to my students, I am constantly searching for new information and ways to open my eyes to the world of food and culture around me and bring more depth of knowledge to my classroom, which is why I decided to further my education at BU.

My name is Sara Sobkoviak and I am a passionate teacher, foodie, traveler, and learner. I received my bachelor’s degree 20 years ago in Mass Media Communications from Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma and I minored in Spanish. I then went on to work in the photography industry and started my own business where I photographed families, individuals, engagements, and weddings (including countless Indian weddings where I sampled many amazing dishes). I have traveled to many Spanish-speaking countries and have been heavily influenced by their cultures and food practices. My interest in food has grown since I was a child in my mother’s kitchen in a small town in Illinois. I continued my passion for food by working in restaurants, for catering companies, and then studying culinary arts near my current home in California. My experiences in these kitchens have taught me so much about the culinary world, and the knowledge I now possess is one that I pass on to my high school students in an “Adulting” program I created. Beyond teaching Spanish and culinary skills to my students, I am constantly searching for new information and ways to open my eyes to the world of food and culture around me and bring more depth of knowledge to my classroom, which is why I decided to further my education at BU.

Course Spotlight: Sociology of Taste

MET ML 716, Sociology of Taste, with Dr. Connor Fitzmaurice, will be offered as a hybrid class in the spring 2022 semester.

Taste has an undeniable personal immediacy: producing visceral feelings ranging from delight to disgust. As a result, in our everyday lives we tend to think about taste as purely a matter of individual preference. However, for sociologists, our tastes are not only socially meaningful, they are also socially determined, organized, and constructed. This course will introduce students to the variety of questions sociologists have asked about taste. What is a need? Where do preferences come from? What social functions might our tastes serve? Major theoretical perspectives for answering these questions will be considered, examining the influence of societal institutions, status seeking behaviors, internalized dispositions, and systems of meaning on not only what we enjoy--but what we find most revolting.

This course is a graduate level seminar where discussion and class participation are central to student success. As such, this class will feature weekly zoom meetings on Thursday evenings throughout the semester from 6:00 pm to 8:45 pm (with a mid-class break!).

Students will be able to take advantage of three in-person learning opportunities during the spring 2022 semester. During these weeks there will be no Thursday evening Zoom meeting:

- Saturday, March 19, 10 am to 12:45 pm - Project workshop, on campus

- Saturday, April 16th from 11:00 am to 1:00 pm (Rain date April 23rd) - Farm visit

- Saturday, April 30th from 10:00 am to 12:45 pm - Final research presentations, on campus

Opportunities for asynchronous participation will be available via blackboard.

This class is open to graduate students and upper level undergraduates. Non-degree seeking students may register here.

Course Spotlight: Sustainable Food Systems

This course will examine the contemporary food system through a multi-disciplinary lens. Taught by Chef Michael Leviton, the course will allow students to put readings and ideas into culinary practice. By examining the often-competing concerns from other domains, including economic (both micro and macro—social), social welfare, social justice and social diversity, health and wellness, food security and insecurity, and resiliency, we can begin to move towards solutions that treat the disease (our food system) and not just the symptoms (domain specific issues). Students will read widely in the topic area, engage in classroom discussion, and work together in the kitchen to understand hands-on culinary approaches to some of the most important issues of our time.

This course will examine the contemporary food system through a multi-disciplinary lens. Taught by Chef Michael Leviton, the course will allow students to put readings and ideas into culinary practice. By examining the often-competing concerns from other domains, including economic (both micro and macro—social), social welfare, social justice and social diversity, health and wellness, food security and insecurity, and resiliency, we can begin to move towards solutions that treat the disease (our food system) and not just the symptoms (domain specific issues). Students will read widely in the topic area, engage in classroom discussion, and work together in the kitchen to understand hands-on culinary approaches to some of the most important issues of our time.

The reading list will be drawn from a wide range of contemporary authors include selections from Michael Pollan's Omnivore's Dilemma, Maryn McKenna’s Big Chicken, Saru Jayaraman‘s Behind the Kitchen Door, and Wenonah Hauter’s Foodopoly . Guest speakers will bring in scholarly and practical approaches being put into use in the contemporary food scene.

Some class meetings will include tastings of different products (different origins, local, heritage, commodity, sustainable, organic, etc.) and cooking instruction around techniques for working with underutilized species, grass-fed (vs grain) beef, pastured vs coop chicken etc.

MET ML 723, Sustainable Food Systems, will meet on Monday nights in the Spring 2022 Semester, beginning on January 23. This class is open to graduate students and upper level undergraduates. Non-degree seeking students may register here.

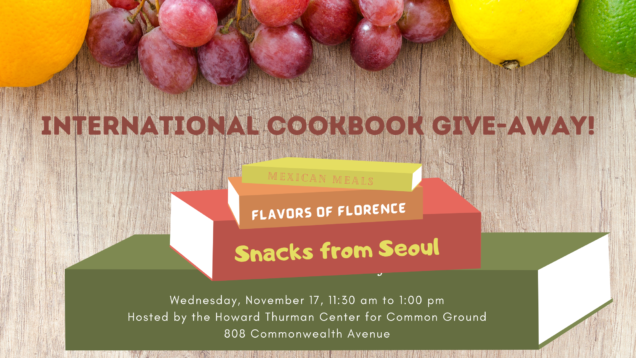

International Education Week Cookbook Giveaway

Wednesday, November 17; 11:30 am to 1:00 pm

Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground

Fuller Building, 808 Commonwealth Avenue

As part of BU's International Education Week, Boston University students, faculty, and staff are invited to explore a new cuisine by choosing a free cookbook at this event. We have culled through our collection for duplicates, so you will be helping us make room on our shelves for some additional titles.

Have you ever wondered what books we have in our collection? You can browse through them virtually here, or contact us to arrange a time to visit the library in person.

Fall 2021 Pépin Lecture Series in Food Studies & Gastronomy

Fall 2020 lectures will be presented in webinar format. Registration is free and open to the public: please follow the link for each program to register.

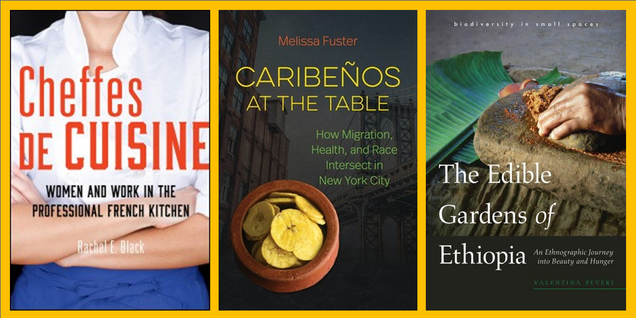

Cheffes de Cuisine: Women and Work in the Professional French Kitchen

Rachel Black, Associate Professor, Anthropology Department Connecticut College

Though women enter France’s culinary professions at higher rates than ever, men still receive the lion’s share of the major awards and Michelin stars. Rachel E. Black looks at the experiences of women in Lyon to examine issues of gender inequality in France’s culinary industry. Known for its female-led kitchens, Lyon provides a unique setting for understanding the gender divide, as Lyonnais women have played a major role in maintaining the city’s culinary heritage and its status as a center for innovation. Voices from history combine with present-day interviews and participant observation to reveal the strategies women use to navigate male-dominated workplaces or, in many cases, avoid men in kitchens altogether. Black also charts how constraints imposed by French culture minimize the impact of #MeToo and other reform-minded movements.

Evocative and original, Cheffes de Cuisine celebrates the successes of women inside the professional French kitchen and reveals the obstacles women face in the culinary industry and other male-dominated professions.

Cosponsored by the BU Women's, Gender & Sexuality Studies Program

Friday, October 15, noon to 1:00 pm. Register here.

Caribeños at the Table: How Migration, Health, and Race Intersect in New York City

Melissa Fuster, Associate Professor, Tulane University School of Public Health

Melissa Fuster thinks expansively about the multiple meanings of comida, food, from something as simple as a meal to something as complex as one’s identity. She listens intently to the voices of New York City residents with Cuban, Dominican, or Puerto Rican backgrounds, as well as to those of the nutritionists and health professionals who serve them. She argues with sensitivity that the migrants’ health depends not only on food culture but also on important structural factors that underlie their access to food, employment, and high-quality healthcare.

People in Hispanic Caribbean communities in the United States present high rates of obesity, diabetes, and other diet-related diseases, conditions painfully highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both eaters and dietitians may blame these diseases on the shedding of traditional diets in favor of highly processed foods. Or, conversely, they may blame these on the traditional diets of fatty meat, starchy root vegetables, and rice. Applying a much needed intersectional approach, Fuster shows that nutritionists and eaters often misrepresent, and even racialize or pathologize, a cuisine’s healthfulness or unhealthfulness if they overlook the kinds of economic and racial inequities that exist within the global migration experience.

Cosponsored by the BU Graduate Programs in Nutrition

Friday, November 12, noon to 1:00 pm. Register here.

The Edible Gardens of Ethiopia: An Ethnographic Journey Into Beauty and Hunger - Biodiversity in Small Spaces

Valentina Peveri, Food Anthropologist, American University of Rome

What is a beautiful garden to southern Ethiopian farmers? Anchored in the author's perceptual approach to the people, plants, land, and food, The Edible Gardens of Ethiopia opens a window into the simple beauty and ecological vitality of an ensete garden.

The ensete plant is only one among the many 'unloved' crops that are marginalized and pushed close to disappearance by the advance of farming modernization and monocultural thinking. And yet its human companions, caught in a symbiotic and sensuous dialogue with the plant, still relate to each exemplar as having individual appearance, sensibility, charisma, and taste, as an epiphany of beauty and prosperity, and even believe that the plant can feel pain. Here a different story is recounted of these human-plant communities, one of reciprocal love at times practiced in an act of secrecy. The plot unfolds from the subversive and tasteful dimensions of gardening for subsistence and cooking in the garden of ensete through reflections on the cultural and edible dimensions of biodiversity to embrace hunger and beauty as absorbing aesthetic experiences in small-scale agriculture. Through this story, the reader will enter the material and spiritual world of ensete and contemplate it as a modest yet inspiring example of hope in rapidly deteriorating landscapes.

Based on prolonged engagement with this 'virtuous' plant of southwestern Ethiopia, this book provides a nuanced reading of the ensete ventricosum (avant-)garden and explores how the life in tiny, diverse, and womanly plots offers alternative visions of nature, food policy, and conservation efforts.

Friday, November 19, noon to 1:00 pm. Register here.