Tagged: Supreme Court

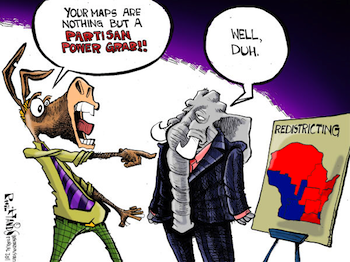

Can Partisan Gerrymandering be Stopped?

Attention to partisan gerrymandering has heightened as the next wave of redistricting fast approaches and the Supreme Court’s 2017-2018 docket included two cases regarding the constitutionality of partisan gerrymander. Following the release of the 2020 census, states will set out to redraw their district maps. States redistrict at least every ten years. The 2010 redistricting results are described as the most extreme partisan gerrymandering in our country’s history. The 2010 maps have a heavy Republican partisan advantage, as evidenced by the 2012 election results with Republicans gaining a 234 to 201 seat advantage in the House of Representatives despite Democrats winning 1.5 million more votes than Republicans. The Republican partisan advantage has remained strong. The Brennan Center for Justice has predicted that in the 2018 midterm elections Democrats will need to win by a margin of nearly 11 points to gain a majority in the House of Representatives. Democrats, however, have not won by a margin this large since 1974. Following years of heavily gerrymandered districts, a supermajority of Americans have indicated support for the Supreme Court to bring an end to partisan gerrymandering, yet the Court failed to take action this year.

Partisan gerrymandering is the carving of districts, into sometimes odd shapes, to benefit a political party’s electoral prospects. The term gerrymandering was coined after Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts’s governor, in order to describe an irregularly shaped district that looked like a salamander in an 1812 redistricting map he signed into law. As a result, partisan gerrymandering has been a defining feature of “American politics since the early days of the Republic.” While racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is an open question, as the Supreme Court has never struck down a map for partisan gerrymander.

Partisan gerrymandering is the carving of districts, into sometimes odd shapes, to benefit a political party’s electoral prospects. The term gerrymandering was coined after Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts’s governor, in order to describe an irregularly shaped district that looked like a salamander in an 1812 redistricting map he signed into law. As a result, partisan gerrymandering has been a defining feature of “American politics since the early days of the Republic.” While racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is an open question, as the Supreme Court has never struck down a map for partisan gerrymander.

Partisan gerrymandering seems to fly in the face of democracy. Voting is a fundamental right and electing who you want to represent you in office is a fundamental part of democracy. Legislatures that scheme, plan, and manipulate maps to benefit one party over another can undermine the purpose of democracy. Some of this scheming, planning, and manipulating is self-interested as legislatures try to protect incumbents and create safe districts, but can also serve the purpose of entrenching a political party’s majority until the next redistricting cycle. Both parties, Republicans and Democrats, have enjoyed the benefit of partisan gerrymandering when given the opportunity.

While the Supreme Court has indicated that some level of partisan gerrymandering may be unconstitutional, it has yet to explain when the constitutional line has been crossed. This term, the Supreme Court took up the question of partisan gerrymandering for the first time in more than a decade. The two cases before the Supreme Court were Gill v. Whitford and Benisek v. Lamone. The Supreme Court was asked to answer when partisan gerrymander crosses the constitutional line. Gill v. Whitford challenged a statewide map that has been deemed among one of the worst partisan gerrymandered maps in the country, with a significant Republican partisan advantage. Benisek v. Lamone challenged one congressional district in Maryland, with a significant Democratic partisan advantage. Some speculated that the Court took up both cases to deter an appearance that the Supreme Court prefers one party over the other. Another reason may be that the Wisconsin case was a challenge to a statewide map compared to the Maryland case challenging one congressional district.

The appellants attorney in Gill v. Whitford argued during oral arguments (see, page 62) that the Supreme Court is the only institution to put an end to partisan gerrymandering. The Court, however, sidestepped the entire issue by unanimously finding the Gill plaintiffs did not have standing, and that the challengers in Benisek had waited too long to seek an injunction blocking the district. The Supreme Court’s silence allows legislatures to continue to strategically gerrymander.

While the country waits on the Supreme Court to provide an answer on the constitutionality of partisan gerrymander, some states have attempted to take partisanship out of the process by using redistricting commissions, while others suggest that computers with algorithms should produce the maps. Yet, neither of these options individually seem to completely insulate redistricting from politics.

States have adopted redistricting commissions with the intention to remove partisanship from the redistricting process. However, this has often proved difficult to achieve, as finding non-partisan committee members is difficult and oftentimes the commission is appointed by partisan members, such as elected representatives and governors. States use different types of commissions and may only use a commission for redistricting the state map or congressional map. About 23 states use commissions for the state legislative maps and about 14 states use commissions for the congressional maps. The redistricting commissions can take the form of an advisory commission that makes suggestions to the legislature, a backup commission that draws the map if the legislature fails to redistrict, or as having the primary responsibility of drawing the map.

Even states that use independent redistricting commissions have had difficulties completely insulating the process from politics. For instance, in 2011, Arizona’s Independent Redistricting Commission chairwoman was removed by the Republican Governor and the Republican-controlled State Senate. The Governor accused the chairwoman of skewing the process for Democrats. The Arizona Supreme Court, however, reinstated the chairwoman and the United States Supreme Court upheld Arizona’s independent redistricting commission as a legitimate way to draw district maps. Although some states are moving toward redistricting commissions as a way to insulate the process from politics, these commissions are “only as independent as those who appoint it.”

While technological advances have been thought to help parties gerrymander more effectively, some suggest that similar technology could take politics out of the process with the proper algorithms. Brian Olson, a Massachusetts software engineer, wrote an algorithm to create “‘optimally compact’ equal-population congressional districts.” Olson prioritized the compactness requirement in an effort to reflect “actual neighborhoods” and because dramatically non-compact districts can be a “telltale sign of gerrymandering.” However, political scientists are skeptical about an algorithm prioritizing compactness, because it ignores other important factors, such as community of interest. Furthermore, someone needs to set the algorithm and there can be infinite map results. Thus, without very strict restrictions and guidelines, setting an algorithm and picking the map can still be an inherent gerrymander.

Removing politics completely from the redistricting process appears to be nearly impossible. Partisanship is deeply entrenched in the process, and dates back to even before the coined term “gerrymander.” Redistricting commissions do not always guarantee a partisan free redistricting effort, and while technology offers an alternative to human map drawing, humans are still making the final decision. Some combination of these efforts may help to lessen the amount of politics used in the redistricting process or lessen the appearance of partisanship, but are unlikely to completely end partisan gerrymandering all together.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Inter Partes Review: non-Article III Adjudication of Private Property Rights

In November 2017, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments for Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group. Oil States poses a question that forces the Supreme Court to consider whether it will turn patent strategy on its head: whether inter partes reviews (IPRs) violate the Constitution by extinguishing private property rights through a non-Article III forum without a jury. The Federal Circuit is notoriously the appellate circuit most reversed by the Supreme Court – by May 2017, the Court had reversed 25 of the 30 cases it accepted from the Federal Circuit. Will Oil States suffer the same fate?

An IPR, established as one of the cornerstones of the American Invents Acts (AIA) in 2011 and initiated in 2012, is a proceeding instituted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), upon petition by an outside party, allowing parties to challenge the validity of an issued patent before the Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB), a non-Article III tribunal. Congress created IPRs primarily to increase the efficiency of an otherwise expensive and time consuming traditional patent validity challenge in court. While traditional patent litigation may consume millions of dollars and years of the parties’ time – a waste of financial and judicial resources and creating uncertainty within the field of technology encompassed by the patent – an IPR typically costs the parties a comparatively small six figure sum and the AIA requires the PTAB to issue a final written decision within one year of IPR institution.

Since 2012, IPRs have become a popular mechanism for parties to challenge the validity of patents – in part due to their efficiency and in part because the PTAB does not begin with a presumption of validity, whereas courts do. In effect, the PTAB has invalidated all claims of the challenged patent in over 1,200 proceedings, roughly 74% of all IPRs. Only 13% of IPRs result in no claims of a patent being invalidated.

The courts have already disposed of numerous challenges to the constitutionality of patent validity review procedures conducted before the USPTO. Before the AIA introduced IPRs, the USPTO had already been invalidating patents since 1981 via ex-parte reexamination. The Federal Circuit has repeatedly affirmed the constitutionality of the USPTO’s authority in such proceedings, stating that “[a] defectively examined and therefore erroneously granted patent must yield to the reasonable Congressional purpose of facilitating the correction of governmental mistakes.” Patlex Corp. v. Mossinghoff, 758 F.2d 594, 604 (Fed. Cir. 1985). The Federal Circuit has more recently denied a similar constitutional challenge to IPRs, stating that patent rights are public rights, reviewable by an administrative agency, and therefore assigning review of patent validity to the USPTO is consistent with Article III. MCM Portfolio LLC v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 812 F.3d 1284, 1291 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

Oil States challenged IPRs alleging a violation of both Article III and the Seventh Amendment. Concerning Article III, Oil States argued that it is unconstitutional for a non-Article III court / Article I tribunal to adjudicate private property. Oil States argued that the Seventh Amendment guarantees patent owners the right to a jury trial because historically, patent infringement cases have been heard in courts of law in England before juries.

Oil States argued that the Supreme Court has once before reviewed and disavowed USPTO patent validity review procedures (otherwise, the Court has only denied certiorari in the past to review Federal Circuit decisions treating the question, including the two above decisions) and the differences in the statutorily created IPR and ex parte reexamination.

In 1898, the Supreme Court held that “the Patent Office has no power to revoke, cancel, or annul” an issued patent. McCormick Harvesting Mach. Co. v. Aultman & Co., 169 U.S. 606 (1898). However, this case did not concern the constitutionality of such proceedings, and it is likely that the Court will limit McCormick to the narrow position that the USPTO does not exercise jurisdiction over an issued patent in the absence of authorization from Congress, as was lacking in 1898. Now that Congress has expressly authorized such review via the AIA, the Court will likely find such review constitutional.

Oil States highlights the differences between AIA-created IPRs and ex parte reexaminations; IPRs are adversarial proceedings including discovery, briefings, hearings, and a final judgment, whereas ex parte reexaminations are more akin to interactive proceedings between the agency and patent owner.

To resolve this case, the Court will likely stay away from disclaiming the statutory distinctions establishing IPRs as trial-like proceedings, because these hold some legitimacy, and focus on whether a patent is a public or private right. If a patent is a public right, then there is no issue with IPRs being trial-like proceedings conducted before non-Article III adjudicators because it is proper for an agency to adjudicate a public regulatory scheme. If, on the other hand, patents are private rights, as Oil States contends, then the Court would be forced to either disavow IPRs or distinguish their characteristics from a trial. The Federal Circuit provided the Court with a mirror distinguishing IPRs from traditional trials, but this distinction is fragile at best. Ultratec, Inc. v. Captioncall, LLC, 2017 WL 3687453, *1 n.2 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 28, 2017). The Court would find more stable grounding classifying patents as quintessential public rights, conferred only by virtue of a statute.

The most curious note regarding the Supreme Court’s decision to hear Oil States is that it concurrently agreed to hear SAS Institute v. Lee, which asks the Court to consider whether the AIA permits the USPTO to select claims from a petition and partially institute an IPR or whether the USPTO must wholly grant or deny a petition, either blessing or damning all claims. If the Court intends to destabilize the AIA and declare IPRs unconstitutional, why consider the USPTO’s duty to the petitioner for an IPR in the same term? It is likely that the Supreme Court will uphold the constitutionality of the AIA’s grant of authority to the USPTO and permit IPRs to continue, but will use these two cases as an opportunity to either limit the scope and effect of IPRs or force clarity regarding the deficiencies of IPRs – such as lacking judicial rules of ethical conduct, improper handling of evidence, improper handling of amendments, or simply disregarding established standards in favor of PTAB-created standards.

Eric Dunbar anticipates graduating Boston University School of Law in May 2018.