Tagged: Maryland

Making Big Tech Pay Their Share: The Taxation of Digital Advertising in Maryland

In sharp contrast to the bevy of tax incentives offered to Amazon as part of a bid for the so-called “HQ2,” Maryland has charted a path towards taxation of technology companies as part of its commitment and obligation to its residents. This move to hold large companies accountable for the money they derive from Maryland residents is laudable, given the amount of data mined from individuals and used to sell targeted digital advertising as well as the crisis of state budget shortages. However, as written, Maryland’s efforts raise serious legal concerns that jeopardize the viability of the current iteration of the bill. The bill draws on an existing model to achieve important social goals. However, in the context of the American legal framework, the current iteration of the bill raises First Amendment freedom of speech concerns and faces further challenges under the commerce clause and federal legislation enacted to promote and facilitate Internet commerce. These shortcomings need not be fatal, though. With modest redrafting, the policy underlying the bill could be implemented in order to fulfill Maryland’s goals.

The bill

Introduced in the Senate as Senate Bill 2 and in the House as House Bill 695, parallel bills in the Maryland legislature impose a

tax on gross revenues derived from digital advertising. The amount ranges from 2.5% for a corporation with annual gross revenues from $100 million to $1 billion up to 10% for those with gross revenues over $15 billion. The revenue raised will go to the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future Fund, which funds K-12 education improvements in the state. This policy, though lauded as the first attempt to tax digital advertising revenues in the United States, is not without global precedent. Rather, it is modeled after a French law, which levies a 3% tax on digital interface and “targeted advertising services” in France. The tax only applies to companies with global revenues from digital interface and targeted advertising of more than €750 million globally, with at least €25 million of which was derived from French users. France enacted this legislation July 11, 2019, and was quickly rebuked by the American business community. In particular, President Trump threatened countermeasures of tariffs up to 100% on $2.4 billion worth of French imports to the United States, including sparkling wine and cheese. As a result, France and the U.S. negotiated a pause on the enactment of the law on the condition that the threatened tariffs not go into place.

Like its French model, Maryland’s bill specifically targets large technology companies. The Fiscal and Policy Note for the Maryland bill calls out by name Alphabet (the parent company of Google), Facebook, and Amazon. Proponents suggest that this legislation will force tech companies to “pay their fair share” by contributing to local tax bases rather than reaping the benefits while paying only minimal tax obligations. However, the opponents are not without their own ammunition. As part of their strategy to defeat the underlying policy, they raise legal questions regarding the current drafting and scope of the bill.

Legal considerations

Opponents argue that the selective taxation represents a content-based restriction on free speech because it selectively targets some kinds of advertising based on its communicative content. Following the recent Supreme Court case of Reed v. Town of Gilbert, which expanded the category of what is considered a content-based restriction on speech, this kind of selective taxation could be viewed as falling into the category of speech subject to strict scrutiny and therefore unlikely to survive judicial review. Even as an exercise of commercial speech, subject only to intermediate scrutiny under Central Hudson Gas & Electric v. Public Service Commission, such a tax is unlikely to be sustained. Restrictions on commercial speech must be no broader than necessary to directly further a substantial government interest. Under these circumstances, improving K-12 education is likely a substantial government interest, but the program could not be considered narrowly tailored. There are other means of raising the necessary revenue without burdening commercial speech of only large technology companies.

Maryland’s tax also raises other, non-First Amendment concerns. As written, the bill could be construed as a violation of the commerce clause of the Constitution, because it would create the possibility of double taxation of the same single economic activity if every state were to adopt a similar regime, violating the “internal consistency” test. A final source of legal concern for the policy is the Permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act, or PITFA. PITFA prohibits state taxation of internet access as well as discrimination against online commerce. The taxation of digital advertising, but not traditional forms of advertising, could be seen as a discrimination against online commerce in violation of PITFA.

Maryland’s tax also raises other, non-First Amendment concerns. As written, the bill could be construed as a violation of the commerce clause of the Constitution, because it would create the possibility of double taxation of the same single economic activity if every state were to adopt a similar regime, violating the “internal consistency” test. A final source of legal concern for the policy is the Permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act, or PITFA. PITFA prohibits state taxation of internet access as well as discrimination against online commerce. The taxation of digital advertising, but not traditional forms of advertising, could be seen as a discrimination against online commerce in violation of PITFA.

Looking forward

The French example and advertising industry outcry against the Maryland proposal suggest that taxation of digital advertising will be a difficult prize to win. Significant political, economic, and legal hurdles remain. However, in an era of declining state revenues and K-12 funding crises, novel solutions must be sought. The digital advertising industry, reaping incredible profits, represents a tempting source of revenue for states dealing with these demands. However, as constructed, the policy presents serious legal shortfalls. This is not to say that the taxation of a major economic activity ought to be abandoned as a policy proposal. Rather, the specific construction of the statute needs to be reconsidered as the Maryland legislature moves forward. For example, a modification in the way that “in the state” is determined for the purposes of the tax could eliminate the concern of double taxation and, therefore, the commerce clause concerns. Where modest redrafting could save the policy from its legal challenges, it seems imperative to do so given the high stakes underpinning the policy.

Jordan Neubauer anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

Jordan Neubauer anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

Raising the Blinds – Gaining Meaningful Insight into Pharmaceutical Pricing through Legislation

Rising healthcare costs are a growing concern across the United States; in 2016 U.S. health care spending was $10,348 per person – or 17.9 % of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). To counter this alarming rise in healthcare costs, states are addressing one of the largest factors in rising healthcare costs – high drug prices.

Many factors contribute to the high price of healthcare in our country, some of which are natural to an aging populace due to the baby boom of the 1950’s as the proportion of the population that is 65 and over is projected to experience a large increase in the coming years. An increase in costs is natural with a larger number of consumers – addressing this change is an important, but avoidable, challenge to overcome.

One avoidable factor of increasing healthcare costs is rapidly increasing pharmaceutical prices. Variance in drug prices may be geographic; based on where the drug is sold , or whom the drug is being sold to (pharmacy v. government). Many factors contribute to price differences, but an important factor are Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) as an intermediate in the market. States have been working to roll back the PBM layer of the market for the pharmaceutical industry.

Pharmaceutical pricing has long been the target of legislators, but with a lot of talk and a surprising lack of action. Drug pricing is discussed in both major party’s campaign platforms of the major parties and has been featured prominently in speeches by President Trump, and has featured in initiatives by previous administrations. There has been an uptick of legislation passed in the past decade, at all levels of government, with state action against pharmacy benefit managers and President Trump’s signing the Know the Lowest Price Act and the Patient Right to Know Drug Prices Act. A common thread in the legislation is increased transparency because a big factor in the high drug prices — and medical care generally—is the lack of information for consumers and purchasers. Since 2015, California, Oregon, Louisiana, Nevada, Vermont, Connecticut, and Maryland imposed reporting requirements on pharmaceutical manufacturers who increase prices over an established threshold in a set time period. For example, California requires reporting when a drug that costs more than $40 and its wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) increases by more than 16% over two calendar years. The WAC is similar to a “list” price for pharmaceuticals to wholesalers and direct purchasers. The WAC, however, does not include discounts or rebates offered by pharmacy benefit managers.

The new transparency offers insight to price increases; if there are no legitimate reason for the increase other than higher profits due to market control, state officials, drug customers and the public can take action.

The states with transparency statutes have imposed different methodologies with manufacturers reporting to different government officials such as the Department of Health and Human Services, creation of new departments, or to the state’s Attorney General.

Oregon currently requires the most detailed reporting; manufacturers must report to the Department of Consumer and Business Services the following:

- Name, price of drug and net increase in price (in %) over previous calendar year

- Length of time on market

- Factors contributing to price increase

- Name(s) of any generic version(s) of the drug

- Research & Develop Costs from Public Funds

- Direct costs to Manufacturer

- Total sales revenue for drug over prev. calendar year

- Profit from drug over previous calendar year

- Drug's price at release and yearly increases over the past 5 years

- 10 highest prices paid for the drug during past year outside of the US

- Any other info relevant to price increase

- Supporting documentation

In contrast, California’s requirements provide for advance notice of price increases and unearthing the reasoning for the increase. The California law requires manufacturers to report (A) Date of increase, current WAC, and future increase in WAC (in dollar amounts); and (B) The change or improvement, if any, that necessitates the price increase. Purchasers then have notice of any forthcoming price changes and if the increase is warranted. California also requires a report for new drugs if its price exceed $670—the 2017 Medicare Part D threshold. California’s reporting scheme has been a model for other states.

Maryland’s approach was more severe, with a provision banning “price gouging” of generic drugs. An “unconscionable price increase” of any “essential off-patent or generic drug” is illegal and Maryland can levy a fine and take action to reverse the price change. The state did not include any limitation of the law to drugs that have come into or passed through Maryland.

The generic drug lobby, the Association for Accessible Medicines, challenged the law and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the law as an unconstitutional regulation of interstate commerce. Maryland has petitioned the Supreme Court to revisit the case.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers (PhRMA), one of the largest pharmaceutical lobbying groups, has sued California alleging the law, like Maryland’s, is unconstitutional. Because California’s law is informational—and does not allow forced price changes—it is likely constitutional. In fact, PhRMA’s initial complaint was dismissed, and subsequently filed an amended complaint on Sept. 18, 2018.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers (PhRMA), one of the largest pharmaceutical lobbying groups, has sued California alleging the law, like Maryland’s, is unconstitutional. Because California’s law is informational—and does not allow forced price changes—it is likely constitutional. In fact, PhRMA’s initial complaint was dismissed, and subsequently filed an amended complaint on Sept. 18, 2018.

It will be imperative for states seeking to regulate pharmaceutical manufacturers to observe where courts determine the extent of reporting they may require when they go after a manufacturer for increasing the price of their drug. For the time being, it appears that information-gathering may be the easiest available avenue for states seeking to curtail increases in drug prices. Seeking justifications and reasoning for large increases in drug prices may create a barrier for pharmacuetical companies seeking to impose unsubstantiated increases in drugs. Going further towards affirmative control of pricing appears to be off limits to states going as far as Maryland, but more careful structuring of the controls to the specific state may be permissible.

Drew Kohlmeier is a student in the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020 and is a native of Manhattan, KS, graduating with a degree in Biology from Kansas State University in 2016. Drew decided on Boston for law school due to his interest in health care and life sciences, and will be practicing in the emerging companies space focused on the life sciences industry following his graduation from BU.

Drew Kohlmeier is a student in the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020 and is a native of Manhattan, KS, graduating with a degree in Biology from Kansas State University in 2016. Drew decided on Boston for law school due to his interest in health care and life sciences, and will be practicing in the emerging companies space focused on the life sciences industry following his graduation from BU.

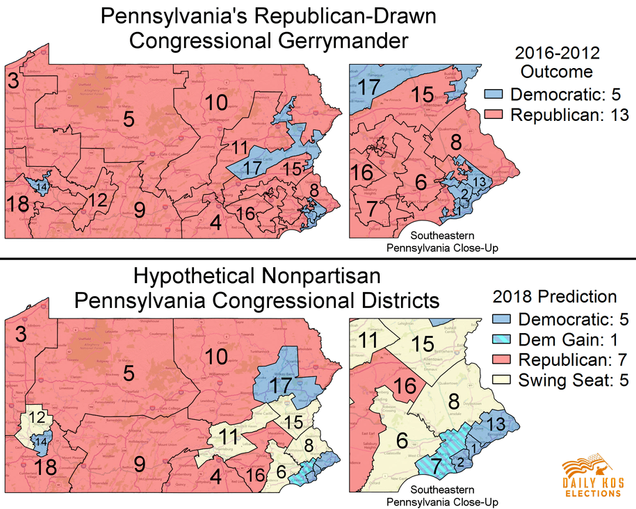

Can Partisan Gerrymandering be Stopped?

Attention to partisan gerrymandering has heightened as the next wave of redistricting fast approaches and the Supreme Court’s 2017-2018 docket included two cases regarding the constitutionality of partisan gerrymander. Following the release of the 2020 census, states will set out to redraw their district maps. States redistrict at least every ten years. The 2010 redistricting results are described as the most extreme partisan gerrymandering in our country’s history. The 2010 maps have a heavy Republican partisan advantage, as evidenced by the 2012 election results with Republicans gaining a 234 to 201 seat advantage in the House of Representatives despite Democrats winning 1.5 million more votes than Republicans. The Republican partisan advantage has remained strong. The Brennan Center for Justice has predicted that in the 2018 midterm elections Democrats will need to win by a margin of nearly 11 points to gain a majority in the House of Representatives. Democrats, however, have not won by a margin this large since 1974. Following years of heavily gerrymandered districts, a supermajority of Americans have indicated support for the Supreme Court to bring an end to partisan gerrymandering, yet the Court failed to take action this year.

Partisan gerrymandering is the carving of districts, into sometimes odd shapes, to benefit a political party’s electoral prospects. The term gerrymandering was coined after Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts’s governor, in order to describe an irregularly shaped district that looked like a salamander in an 1812 redistricting map he signed into law. As a result, partisan gerrymandering has been a defining feature of “American politics since the early days of the Republic.” While racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is an open question, as the Supreme Court has never struck down a map for partisan gerrymander.

Partisan gerrymandering is the carving of districts, into sometimes odd shapes, to benefit a political party’s electoral prospects. The term gerrymandering was coined after Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts’s governor, in order to describe an irregularly shaped district that looked like a salamander in an 1812 redistricting map he signed into law. As a result, partisan gerrymandering has been a defining feature of “American politics since the early days of the Republic.” While racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is an open question, as the Supreme Court has never struck down a map for partisan gerrymander.

Partisan gerrymandering seems to fly in the face of democracy. Voting is a fundamental right and electing who you want to represent you in office is a fundamental part of democracy. Legislatures that scheme, plan, and manipulate maps to benefit one party over another can undermine the purpose of democracy. Some of this scheming, planning, and manipulating is self-interested as legislatures try to protect incumbents and create safe districts, but can also serve the purpose of entrenching a political party’s majority until the next redistricting cycle. Both parties, Republicans and Democrats, have enjoyed the benefit of partisan gerrymandering when given the opportunity.

While the Supreme Court has indicated that some level of partisan gerrymandering may be unconstitutional, it has yet to explain when the constitutional line has been crossed. This term, the Supreme Court took up the question of partisan gerrymandering for the first time in more than a decade. The two cases before the Supreme Court were Gill v. Whitford and Benisek v. Lamone. The Supreme Court was asked to answer when partisan gerrymander crosses the constitutional line. Gill v. Whitford challenged a statewide map that has been deemed among one of the worst partisan gerrymandered maps in the country, with a significant Republican partisan advantage. Benisek v. Lamone challenged one congressional district in Maryland, with a significant Democratic partisan advantage. Some speculated that the Court took up both cases to deter an appearance that the Supreme Court prefers one party over the other. Another reason may be that the Wisconsin case was a challenge to a statewide map compared to the Maryland case challenging one congressional district.

The appellants attorney in Gill v. Whitford argued during oral arguments (see, page 62) that the Supreme Court is the only institution to put an end to partisan gerrymandering. The Court, however, sidestepped the entire issue by unanimously finding the Gill plaintiffs did not have standing, and that the challengers in Benisek had waited too long to seek an injunction blocking the district. The Supreme Court’s silence allows legislatures to continue to strategically gerrymander.

While the country waits on the Supreme Court to provide an answer on the constitutionality of partisan gerrymander, some states have attempted to take partisanship out of the process by using redistricting commissions, while others suggest that computers with algorithms should produce the maps. Yet, neither of these options individually seem to completely insulate redistricting from politics.

States have adopted redistricting commissions with the intention to remove partisanship from the redistricting process. However, this has often proved difficult to achieve, as finding non-partisan committee members is difficult and oftentimes the commission is appointed by partisan members, such as elected representatives and governors. States use different types of commissions and may only use a commission for redistricting the state map or congressional map. About 23 states use commissions for the state legislative maps and about 14 states use commissions for the congressional maps. The redistricting commissions can take the form of an advisory commission that makes suggestions to the legislature, a backup commission that draws the map if the legislature fails to redistrict, or as having the primary responsibility of drawing the map.

Even states that use independent redistricting commissions have had difficulties completely insulating the process from politics. For instance, in 2011, Arizona’s Independent Redistricting Commission chairwoman was removed by the Republican Governor and the Republican-controlled State Senate. The Governor accused the chairwoman of skewing the process for Democrats. The Arizona Supreme Court, however, reinstated the chairwoman and the United States Supreme Court upheld Arizona’s independent redistricting commission as a legitimate way to draw district maps. Although some states are moving toward redistricting commissions as a way to insulate the process from politics, these commissions are “only as independent as those who appoint it.”

While technological advances have been thought to help parties gerrymander more effectively, some suggest that similar technology could take politics out of the process with the proper algorithms. Brian Olson, a Massachusetts software engineer, wrote an algorithm to create “‘optimally compact’ equal-population congressional districts.” Olson prioritized the compactness requirement in an effort to reflect “actual neighborhoods” and because dramatically non-compact districts can be a “telltale sign of gerrymandering.” However, political scientists are skeptical about an algorithm prioritizing compactness, because it ignores other important factors, such as community of interest. Furthermore, someone needs to set the algorithm and there can be infinite map results. Thus, without very strict restrictions and guidelines, setting an algorithm and picking the map can still be an inherent gerrymander.

Removing politics completely from the redistricting process appears to be nearly impossible. Partisanship is deeply entrenched in the process, and dates back to even before the coined term “gerrymander.” Redistricting commissions do not always guarantee a partisan free redistricting effort, and while technology offers an alternative to human map drawing, humans are still making the final decision. Some combination of these efforts may help to lessen the amount of politics used in the redistricting process or lessen the appearance of partisanship, but are unlikely to completely end partisan gerrymandering all together.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.